The Chinese people commemorated the 130th birthday of Chairman Mao Zedong, the founder of New China, which fell on December 26, in numerous ways, from solemn gatherings at the highest level to countless informal and spontaneous gatherings throughout the country.

On the morning of December 26, Cai Qi, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee presided over a symposium in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People.

Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, Chinese President, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, delivered an important speech. Xi emphasised that:

- Mao was a great Marxist, and a great proletarian revolutionary, strategist, and theorist.

- He was a great trailblazer in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context, and laid the groundwork of China’s socialist modernisation.

- He was a great patriot and national hero in modern Chinese history and the core of the Party’s first generation of central leadership.

- He was a great man who led the Chinese people to change their destiny and the nation as a whole, and

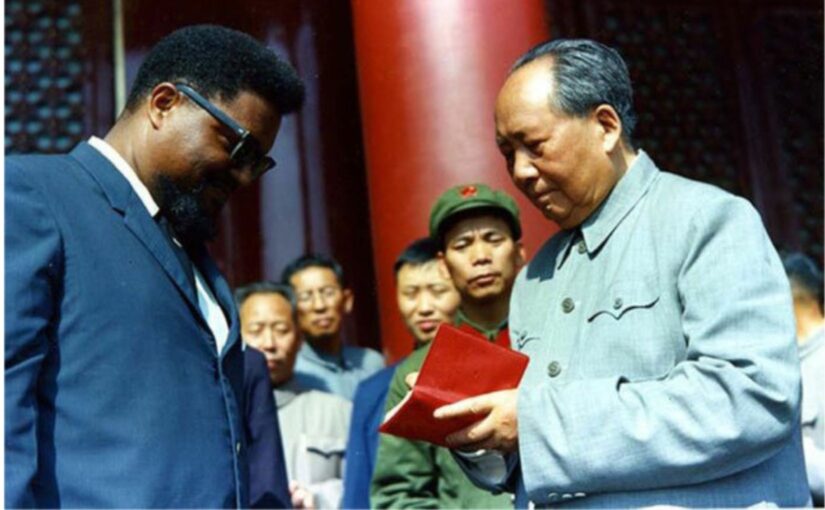

- A great internationalist who made significant contributions to the liberation of oppressed nations and the cause of human progress worldwide.

Mao Zedong Thought, the Chinese leader added, is the precious spiritual asset of our Party and will continue to guide what we do for a long time to come. The best way to commemorate Mao is to continuously advance the cause he initiated.

Xi pointed out that Mao devoted his life to achieving national prosperity, rejuvenating the Chinese nation, and promoting people’s well-being. He led the people in starting the historical process of adapting Marxism to the Chinese context, forging the great, glorious, and correct Communist Party of China, founding the New China with the people enjoying the status as masters of the country, creating an advanced socialist system, and building a new model of people’s army that is invincible. He made indelible historical contributions to the Chinese nation and the Chinese people and made shining contributions that will go down in history.

Xi further emphasised that Comrade Mao Zedong dedicated his entire life to the Party and the people, leaving behind a lofty and inspirational spirit for future generations. Comrade Mao, as a great revolutionary leader, demonstrated far-sighted political vision, firm revolutionary conviction, extraordinary courage to blaze a new trail, perfect art of waging struggle, outstanding leadership, deep concern for the people, an open and broad-minded demeanour, and an exemplary work ethic of hard endeavour. As a result, he earned the love and respect of the entire Party and people of all ethnic groups. Comrade Mao’s noble spirit will forever be a motivating force inspiring us to forge ahead.

On the new journey, he continued, we must never forget our original aspiration and founding mission, be confident in our history, and take historical initiative to continuously advance the great cause of Chinese modernisation.

Chinese modernisation, Xi noted, is the cause of the Chinese people, and we must closely rely on the people, pool the inexhaustible wisdom and strength inherent in the people, and fully motivate the historical initiative of the people. It is crucial to adhere to the fundamental viewpoint of historical materialism that the people are the fundamental driving force in creating history, uphold the people’s principal position, take it as the fundamental purpose of our work to defend, realise and develop the fundamental interests of the vast majority of the people, so as to ensure that all the Chinese people share the achievements of modernisation in a more equitable manner. Efforts should be made to establish systems that ensure the people’s status as masters of the country, improve the mechanisms that uphold social fairness and justice, focus on ensuring and improving people’s well-being, follow the mass line in the new era, always maintain a close connection with the people, accept criticism and supervision from the people, always breathe the same air as the people, share the same future, and stay truly connected to them, in order to provide the most reliable, profound, and sustainable source of strength for advancing Chinese modernisation.

Xi emphasised that reform and opening up is a major reason why China is able to catch up with the times, and it is the key move that determines whether Chinese modernisation will succeed and went on to stress the need to continuously liberate and develop the social productive forces and unleash and enhance social vitality. It is imperative to adapt to the new trends of the times, meet the new requirements of development, and fulfil the new expectations of the people, he said.

Xi pointed out that Chinese modernisation is the socialist modernisation led by the CPC. Only by always staying alert and determined to tackle the unique challenges that a large party like ours faces, and by strengthening the Party more vigorously, can we ensure that Chinese modernisation advances through waves and storms, and steadily moves forward.

It is important to continue to take coordinated steps to see that officials do not have the audacity, opportunity, or desire to become corrupt, so that the Party can remain true to its original aspiration and mission, and at the forefront of the times, and always stay vibrant and vigorous. By doing so, we can ensure that the Party will never change its nature, its conviction, or its character.

Cai Qi, chairing the meeting, noted how affectionately General Secretary Xi, in his important speech, had looked back upon the great practices of Comrade Mao Zedong in leading China’s revolution and construction, and how he has recognised the monumental achievements Comrade Mao Zedong made for the Chinese nation and Chinese people. He went on to note that Xi had proposed explicit requirements for commemorating Comrade Mao Zedong with concrete actions and with efforts to push ahead with the magnificent cause of Chinese modernisation.

Before the symposium, Xi Jinping and other leaders visited the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall where, in accordance with the Chinese custom denoting the highest respect, they bowed three times to the seated statue of Comrade Mao Zedong, and then proceeded to pay respects to his remains.

A further symposium marking the 130th anniversary of the birth of Mao was held in Beijing from December 26-28. At the opening ceremony, Cai Qi stressed the importance of honouring the monumental achievements made by Comrade Mao Zedong, passing on his thought and lofty spirit, advocating the great founding spirit of the Party, and making greater progress in theoretical studies. Cai called on social scientists and theoretical researchers to produce more high-quality research findings in the study of Mao Zedong Thought.

Probably the largest gathering held around the country was that in Mao’s birthplace, Shaoshan, where more than 110,000 people from around the country gathered, with spontaneous mass celebrations and commemorative activities beginning on the afternoon of December 25.

The Chinese newspaper Global Times quoted a middle aged woman from Yunnan province in south-west China as saying that she was surprised and excited to join tens of thousands of people singing, dancing, reciting poems, and waving flags on Mao Zedong Square at midnight.

Another impressive point for her was the large number of young people present. “I used to think that only middle-aged people and the older generation felt strongly about Chairman Mao. It wasn’t until I arrived here that I realised there are so many young people who respect and remember the stories about Chairman Mao,” she said. “Our younger generation is full of vitality and hope.”

The paper further reported a 21-year-old college student as having animated discussions with the older generation on the square. He defined his feelings for Mao Zedong as “sublime faith.”

“As young people of the new generation, we have never forgotten Chairman Mao’s contributions to the Chinese people,” he told the Global Times. “It is our responsibility as young people to inherit the Chairman’s revolutionary spirit and become the backbone of China.”

He added that some Western media and politicians have interpreted young people’s worshipping Mao Zedong as representing a narrow nationalism, but he rejected this saying:

“Our feelings for Chairman Mao are not narrow worship, but a hope to inherit his idea that ‘the world belongs to the people.’ The ultimate ideal is world harmony. How could this be a form of narrow nationalism?”

On the morning of December 26, visitors from across China, gathered in Shaoshan, were served a free breakfast of birthday noodles, recalling that the Chairman had never celebrated his birthday in his lifetime, simply eating a bowl of noodles. They then gathered again at Mao Zedong Square, where a flower laying ceremony was held, and everyone present bowed to Mao Zedong’s statue, followed by the many thousands of people singing together the revolutionary song “The East is Red,” written in praise of Mao Zedong.

The following articles were originally published by the Xinhua News Agency and Global Times.