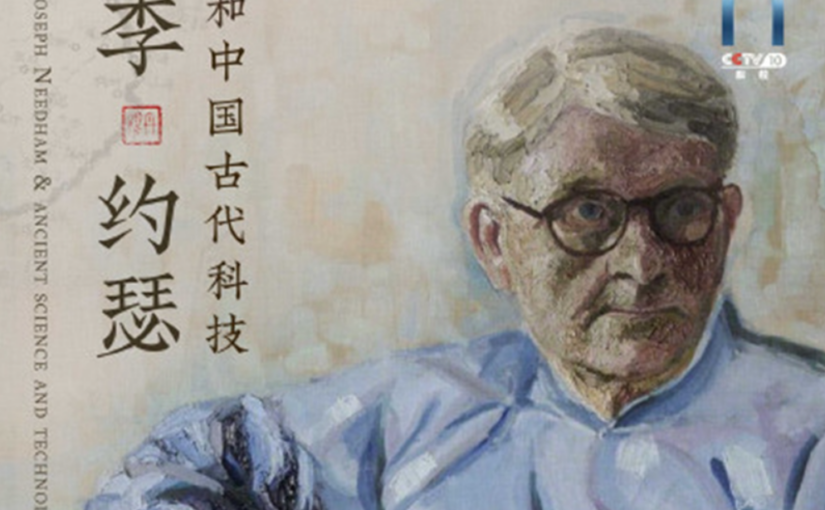

We are pleased to reproduce the below article by John Bellamy Foster, editor of the prestigious socialist journal, Monthly Review, who is also professor of sociology at the University of Oregon, concerning the contributions of the late Dr. Joseph Needham (1900-1995) to the understanding of the deep roots of China’s views on an ecological civilisation in particular and the dialectical nature of much of traditional Chinese philosophy and culture more generally. The article is especially important in that, whilst the contribution of Needham, who, at the time of his death was described by Britain’s Independent newspaper as “possibly the greatest scholar since Erasmus”, to the understanding of science and civilisation in China, the title of his monumental, multi-volume, lifelong work, remains known in some relevant academic circles, for example through the work of the Needham Research Institute, and somewhat more generally through a popular biography by Simon Winchester, his lifelong Marxism, and his significant contributions to Marxist theory, have been all but forgotten.

Bellamy Foster begins by posing the question as to why the most developed version of ecological Marxism is to be found today in China and argues:

“The answer is that there is a much more complex dialectical relation between East and West with respect to materialist dialectics and critical ecology than has been generally supposed, one that stretches back over millennia.”

He further explains that:

“Materialist and dialectical conceptions of nature and history do not start with Karl Marx. The roots of ‘organic naturalism’ and ‘scientific humanism,’ according to the great British Marxist scientist and Sinologist Joseph Needham (李約瑟), author of Science and Civilisation in China, can be traced to the sixth to third centuries BCE both in ancient Greece, beginning with the pre-Socratics and extending to the Hellenistic philosophers, and in ancient China, with the emergence of Daoist and Confucian philosophers during the Warring States Period of the Zhou Dynasty.”

In ‘Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West’, a 1969 book by Needham, the author noted “the absolute alacrity with which ‘dialectical materialism’ was taken up in China during the Chinese Revolution… The Marxian materialist dialectic, with its deep-seated ecological critique rooted in ancient Epicurean materialism, was in Needham’s view, so closely akin to Chinese Daoist and Confucian philosophies as to create a strong acceptance of Marxian philosophical views in China, particularly since China’s own perennial philosophy was in this roundabout way integrated with modern science. If Daoism was a naturalist philosophy, Confucianism was associated, Needham wrote, with ‘a passion for social justice.'”

Bellamy Foster further notes that: “The Needham thesis, as presented here, can also throw light on the spurious proposition, recently put forward by cultural theorist Jeremy Lent, author of The Patterning Instinct, that the Chinese conception of ecological civilisation is derived entirely from China’s own traditional philosophy, rather than being influenced by Marxism. Lent’s argument fails to acknowledge that ecological civilisation as a critical category was first introduced by Marxist environmentalists in the Soviet Union in its closing decades, and immediately adopted by Chinese thinkers, who were to develop it more fully.”

He acknowledges that, “of course, the Needham thesis may seem obscure at first from the usual standpoint of the Western left”, one reason being a “deep Eurocentrism characteristic of contemporary Marxism in the West, associated with the systematic downplaying of colonialism and imperialism.”

But, also citing the work of the late Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin, Bellamy Foster quotes Needham as explaining that “the basic fallacy of Europocentrism is therefore the tacit assumption that because modern science and technology, which grew up indeed in post-Renaissance Europe, are universal, everything else European is universal also.” However, Bellamy Foster continues:

“Marxist thought and socialism in general have always been radically opposed to Eurocentrism, understood as the ideology of Western colonialism. This is as true of Marx and Frederick Engels, particularly in their later years, as it was of V.I. Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg. In the twentieth century, moreover, the impetus for revolution shifted to the Global South and its struggle against imperialism, generating in the process new Marxist analyses in the works of figures as distinct as Mao Zedong, Amílcar Cabral, and Che Guevara, all of whom insisted on the need for a world revolution.”

Whilst it is possible to point to traces of European ethnocentrism in some of Marx’s early work, Bellamy Foster notes that, by the late 1850s, he had “become increasingly focused on the critique of colonialism, actively supporting anti-colonial rebellions, and progressively more concerned with analysing the material and cultural conditions of non-Western societies.” This was “further facilitated by the ‘revolution in ethnological time’ with the discovery of prehistory and the rise of anthropological studies, occurring in tandem with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.” In this regard, Bellamy Foster draws a line of demarcation with the recent influential work, ‘Marx in the Anthropocene‘ by the Japanese Marxist Kohei Saito.

Bellamy Foster draws out the connection between Needham’s pioneering work and Xi Jinping’s thoughts on this issue, citing Chinese scholar Huang Chengliang explaining that “the theoretical origins of Xi Jinping’s thought on Ecological Civilisation can be traced to five sources: (1) Marxist philosophy, integrating “the three fundamental theories of ‘dialectics of history, dialectical materialism and dialectics of nature’”; (2) traditional Chinese ecological wisdom on “[human]-nature unity and the law of nature”; (3) the actual historical context of ecological governance in China in response to the ecological crisis; (4) struggles to develop a progressive and ecological model of sustainable development; and (5) the articulation of ecological civilisation as the governing principle of the new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

He concludes:

“In Xi’s analysis, the traditional Chinese emphasis on the harmony of humanity and nature, or the view that ‘the human and heaven are united in one,’ is wedded to Marxian ecological views with a seamlessness that can only be explained in terms of Needham’s thesis of the correlative development of organic materialism in both the East and West, with Marxism as the connecting link. From this perspective, the Chinese notion of ecological civilisation, due to its overall theoretical coherence and coupled with China’s rise in general, is likely to play an increasingly prominent role in the development of ecological Marxism worldwide. As Needham wrote: ‘China has in her time learnt much from the rest of the world; now perhaps it is time for the nations and the continents to learn again from her.’”

This article, first published in Monthly Review, is based on a talk presented online to the School of Marxism, Shandong University, in Jinan, in March 2023 and was revised and expanded from an original published version, printed in International Critical Thought, a journal of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Ecological materialism, of which ecological Marxism is the most developed version, is often seen as having its origins exclusively within Western thought. But if that is so, how do we explain the fact that ecological Marxism has been embraced as readily (or indeed, more readily) in the East as in the West, leaping over cultural, historical, and linguistic barriers and leading to the current concept of ecological civilization in China? The answer is that there is a much more complex dialectical relation between East and West with respect to materialist dialectics and critical ecology than has been generally supposed, one that stretches back over millennia.

Materialist and dialectical conceptions of nature and history do not start with Karl Marx. The roots of “organic naturalism” and “scientific humanism,” according to the great British Marxist scientist and Sinologist Joseph Needham (李約瑟), author of Science and Civilization in China, can be traced to the sixth to third centuries BCE both in ancient Greece, beginning with the pre-Socratics and extending to the Hellenistic philosophers, and in ancient China, with the emergence of Daoist and Confucian philosophers during the Warring States Period of the Zhou Dynasty.1 As Samir Amin indicated in his Eurocentrism, the “philosophy of nature [as opposed to metaphysics] is essentially materialist” and constituted a “key breakthrough” in tributary modes of production, both East and West, beginning in the fifth century BCE.2

In Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West in 1969, Needham noted the absolute alacrity with which “dialectical materialism” was taken up in China during the Chinese Revolution and how this was treated as a great mystery in the West. Nevertheless, the sense of mystery, he contended, did not extend in the same way to the East itself. He wrote: “I can almost imagine Chinese scholars,” confronted with Marxian materialist dialectics, “saying to themselves ‘How astonishing: this is very like our own philosophia perennis integrated with modern science at last come home to us.’”3 The Marxian materialist dialectic, with its deep-seated ecological critique rooted in ancient Epicurean materialism, was in Needham’s view, so closely akin to Chinese Daoist and Confucian philosophies as to create a strong acceptance of Marxian philosophical views in China, particularly since China’s own perennial philosophy was in this roundabout way integrated with modern science. If Daoism was a naturalist philosophy, Confucianism was associated, Needham wrote, with “a passion for social justice.”4

The Needham convergence thesis—or simply the Needham thesis, as I am calling it here—was thus that Marxist materialist dialectics had a special affinity with Chinese organic naturalism as represented especially by Daoism, which was similar to the ancient Epicureanism that lay at the foundations of Marx’s own materialist conception of nature. Like other Marxist scientists and cultural figures associated with what has been called the “second foundation of Marxism,” centered in Britain in the mid-twentieth century, Needham saw Epicureanism as providing many of the initial theoretical principles on which Marxism, as a critical-materialist philosophy, was based.5 It was the similar evolution of organic materialism East and West—but which, in the case of Marxism, was integrated with modern science—that explained dialectical materialism’s profound impact in China.6

Continue reading Marxian Ecology, East and West: Joseph Needham and a non-Eurocentric view of the origins of China’s ecological civilisation