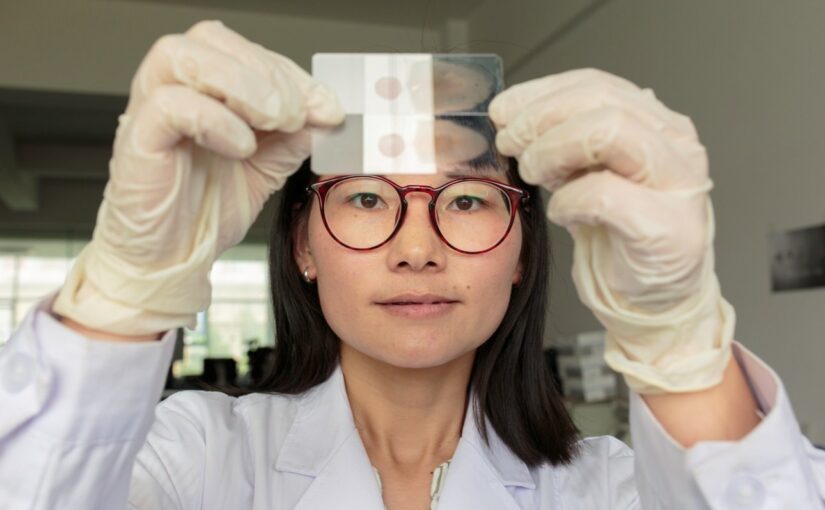

We are republishing this press release from the World Health Organization (WHO) certifying China as malaria-free. This is an extraordinary achievement and a testament to China’s people-centred public health strategy. We also note that China is working with several other countries to share its experience in support of their anti-malaria efforts.

Following a 70-year effort, China has been awarded a malaria-free certification from WHO – a notable feat for a country that reported 30 million cases of the disease annually in the 1940s.

“Today we congratulate the people of China on ridding the country of malaria,” said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General. “Their success was hard-earned and came only after decades of targeted and sustained action. With this announcement, China joins the growing number of countries that are showing the world that a malaria-free future is a viable goal.”

China is the first country in the WHO Western Pacific Region to be awarded a malaria-free certification in more than 3 decades. Other countries in the region that have achieved this status include Australia (1981), Singapore (1982) and Brunei Darussalam (1987).

“Congratulations to China on eliminating malaria,” said Dr Takeshi Kasai, Regional Director, WHO Western Pacific Regional Office. “China’s tireless effort to achieve this important milestone demonstrates how strong political commitment and strengthening national health systems can result in eliminating a disease that once was a major public health problem. China’s achievement takes us one step closer towards the vision of a malaria-free Western Pacific Region.”

Globally, 40 countries and territories have been granted a malaria-free certification from WHO – including, most recently, El Salvador (2021), Algeria (2019), Argentina (2019), Paraguay (2018) and Uzbekistan (2018).

China’s elimination journey

Beginning in the 1950s, health authorities in China worked to locate and stop the spread of malaria by providing preventive antimalarial medicines for people at risk of the disease as well as treatment for those who had fallen ill. The country also made a major effort to reduce mosquito breeding grounds and stepped up the use of insecticide spraying in homes in some areas.

In 1967, the Chinese Government launched the “523 Project” – a nation-wide research programme aimed at finding new treatments for malaria. This effort, involving more than 500 scientists from 60 institutions, led to the discovery in the 1970s of artemisinin – the core compound of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), the most effective antimalarial drugs available today.

“Over many decades, China’s ability to think outside the box served the country well in its own response to malaria, and also had a significant ripple effect globally,” notes Dr Pedro Alonso, Director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme. “The Government and its people were always searching for new and innovative ways to accelerate the pace of progress towards elimination.”

In the 1980s, China was one of the first countries in the world to extensively test the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) for the prevention of malaria, well before nets were recommended by WHO for malaria control. By 1988, more than 2.4 million nets had been distributed nation-wide. The use of such nets led to substantial reductions in malaria incidence in the areas where they were deployed.

By the end of 1990, the number of malaria cases in China had plummeted to 117 000, and deaths were reduced by 95%. With support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, beginning in 2003, China stepped up training, staffing, laboratory equipment, medicines and mosquito control, an effort that led to a further reduction in cases; within 10 years, the number of cases had fallen to about 5000 annually.

In 2020, after reporting 4 consecutive years of zero indigenous cases, China applied for an official WHO certification of malaria elimination. Members of the independent Malaria Elimination Certification Panel travelled to China in May 2021 to verify the country’s malaria-free status as well as its programme to prevent re-establishment of the disease.

Keys to success

China provides a basic public health service package for its residents free of charge. As part of this package, all people in China have access to affordable services for the diagnosis and treatment of malaria, regardless of legal or financial status.

Effective multi-sector collaboration was also key to success. In 2010, 13 ministries in China – including those representing health, education, finance, research and science, development, public security, the army, police, commerce, industry, information technology, media and tourism – joined forces to end malaria nationwide.

In recent years, the country further reduced its malaria caseload through a strict adherence to the timelines of the “1-3-7” strategy. The “1” signifies the one-day deadline for health facilities to report a malaria diagnosis; by the end of day 3, health authorities are required to confirm a case and determine the risk of spread; and, within 7 days, appropriate measures must be taken to prevent further spread of the disease.

Keeping malaria at bay

The risk of imported cases of malaria remains a key concern, particularly in southern Yunnan Province, which borders 3 malaria-endemic countries: Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Viet Nam. China also faces the challenge of imported cases among Chinese nationals returning from sub-Saharan Africa and other malaria-endemic regions.

To prevent re-establishment of the disease, the country has stepped up its malaria surveillance in at-risk zones and has engaged actively in regional malaria control initiatives. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained trainings for health providers through an online platform and held virtual meetings for the exchange of information on malaria case investigations, among other topics.