We are very pleased to reprint the following article by Efe Can Gürcan, which was originally published in BRIQ Belt and Road Quarterly, Volume 5, Issue 1.

In his article, Dr. Gürcan, who is currently a Visiting Scholar at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and is a member of the FoSC Britain Committee, argues that the global political economy has long been characterised by the commanding presence of the US dollar – a linchpin that has steadfastly upheld US hegemony across decades. He further endeavours to illuminate the multifaceted interconnections between a multipolar world and the potential reconfiguration of the dollar’s global standing. His findings suggest that China emerges as the principal contender to US hegemony, spearheading initiatives aimed at dedollarisation, with the prevailing trajectory being towards asset diversification in a post-hegemonic context. Evident manifestations of such inclinations are China’s policies on RMB internationalisation, exemplified by the introduction of the CIPS (Cross-Border Interbank Payment System), UnionPay, and the Digital Yuan. These strategies complement the growing prevalence of bilateral trade in alternative currencies, a growing intention to conduct oil trading in non-dollar currencies, currency swap agreements, and the prospective advent of a BRICS currency. Institutionally, this shift is anchored in frameworks such as the New Development Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The mounting view of dollar dominance as a manipulative instrument of US foreign policy, coupled with the perceived waning of US hegemony and diminishing confidence in the US dollar, impels developing nations to hasten their currency diversification pursuits. This momentum is observed particularly within the framework of South-South cooperation, with China’s proactive stance being a pivotal influence.

Developing his argument, Efe explains that this emergence of multiple power centres, each with its own economic and political clout, threatens to reshape the traditional dynamics of international economic relations, challenging the very sanctity of the dollar’s global supremacy.

He also considers it relevant to address the negative implications of dollarisation for the developing world. Adjustments in US monetary policy have frequently precipitated debt, exchange rate, and financial crises in various developing economies. Noteworthy instances include the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, and the 2018 exchange rate crises in Türkiye, Brazil, Argentina, and other economies, sparked by an increase in US dollar interest rates. Therefore, dollarisation is typically linked with high and unstable inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, and undisciplined monetary policy.

Global confidence in the US dollar has been foundational to its dominance. Such confidence has roots in the United States’ past contributions to global production, its unrivalled military prowess, and its capacity to maintain its currency’s purchasing power through technological advancements and a robust service sector. However, recent geopolitical shifts and the multipolarisation of world politics appear to be eroding this global confidence. China’s ascent as the leading producer and exporter of high-tech goods, combined with the repercussions of the 2007-2008 financial crisis and US military challenges in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, have raised questions about the dollar’s unassailable position.

He cites the work of Daniel McDowell to emphasise that sanctions are a crucial tool in the strategic use of the dollar to counter the emerging powers threatening US hegemony. Primary sanctions aim to directly isolate the targeted individual, company, or government from the dollar-based financial system. In turn, secondary sanctions are designed to exclude the target from global financial networks through the involvement of foreign financial institutions.

Turning to the trend towards dedollarisation, he explains that it emerged against the backdrop of the unprecedented rise of the Latin American left in the 2000s as an important catalyst in multipolarisation, which includes Lula’s Brazil, a leading BRICS+ member. Multipolarisation of the global political economy, he adds, goes hand in hand with the rise of South-South cooperation, embodied not only in the rise of the Latin American left and its social justice-oriented regionalism, but also in the proliferation of Eurasia’s security-oriented regionalism, including the SCO, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, and other cooperation schemes such as the BRICS+, BRI, and the AIIB. These organisations hold the potential to serve as conduits for dedollarisation in forthcoming years.

Particularly significant are trends in the global energy market. If Saudi Arabia and potentially other Gulf countries start trading oil in yuan or other currencies, this would significantly erode the dollar’s dominant position in global energy markets. Additionally, the March 2023 agreement between Chinese and French energy companies to settle an LNG deal in yuan is also of historic importance. Given the magnitude and importance of energy deals, conducting transactions in currencies other than the dollar could set a precedent for future trade agreements. Equally important is China’s recent move to use the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange as a platform for yuan settlements with Arab Gulf nations, a strategic effort to bypass the US dollar in energy trade. Given the vast volumes of oil and gas traded between the Gulf and China, this shift could have a significant impact on the demand for the US dollar in global energy markets. A similar situation goes for nuclear energy. The 2023 agreement between Bangladesh and Russia to use the Renminbi for the settlement of a nuclear plant transaction is yet another sign of countries seeking alternatives to the US dollar for significant infrastructure and development projects.

In this evolving landscape, therefore, China is seizing the opportunity to amplify its global financial footprint. In fact, China’s push to reform the dollar-centric global financial system began following the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Dai Xianglong, who was then the Governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), expressed in 1999 that the instability caused by the dominant role of a few national currencies as international reserve currencies, as well as the system’s failure to address balance of payments imbalances, leads to international financial crises. In the wake of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, Zhou Xiaochuan, Dai’s successor, emphasised the need to overhaul the international monetary system. He proposed an international reserve currency that would be independent of individual nations and identified the weakening dollar as a key factor in the global economic crisis.

China’s endeavours to reduce reliance on the US dollar and bolster the international stature of its currency, the RMB, have involved strategic maneuvers in global financial diplomacy. An integral part of this strategy has been the establishment of currency swap agreements with developing nations. By 2017, China had entered into swap agreements that amounted to more than $500 billion with 35 countries. Both the number of countries and amount of funds involved have continued to increase significantly.

China’s proactive steps towards dedollarisation and establishing the RMB as an international currency have manifested in various other innovative financial undertakings. Initiated in 2002, China’s UnionPay credit card system was instituted as a competitor to globally renowned credit card giants, Visa and MasterCard. By 2019, UnionPay’s ascendancy in the global credit card market was evident, as it held the lion’s share, accounting for 45% of credit cards in circulation. This significant development is not merely about market competition. It represents a strategic move to offer an alternative financial lifeline to nations, such as Russia, Iran, and Cuba, which, due to Western sanctions, find themselves estranged from the dominant international payment systems.

The advantages of the Digital Yuan are manifold. Beyond expediting financial transactions, the use of this blockchain-driven technology enhances China’s capability for comprehensive financial oversight and synchronisation – key attributes for maintaining a robust economy.

And the BRI stands out as one of China’s most ambitious global projects. While the initiative primarily focuses on infrastructural development and connectivity across continents, it also carries significant financial implications. By financing projects within the BRI framework, China can encourage or even mandate the use of yuan for transactional purposes, thereby promoting its global usage. If the BRI projects are primarily transacted in yuan, it could lead to an increased demand for the currency, thereby internationalising it and challenging the dominance of the US dollar.

Presently, dedollarisation represents a nascent trend, predominantly evident in developing nations seeking to diversify their monetary assets. In this context, the notion of “post-hegemony” encompasses not only the relative waning of US global influence and the rise of alternative power hubs, but also the burgeoning South-South collaboration.

Towards the conclusion of his article, Efe turns his attention specifically to Türkiye, which, he outlines, has articulated on multiple occasions its interest in deepening ties with non-Western multilateral organisations. Ankara has repeatedly signaled its intention to explore membership possibilities within the SCO and BRICS, two prominent platforms that present alternatives to the Western-centric global order. Furthermore, Türkiye’s engagement with the BRI is noteworthy. Within the BRI framework, Türkiye has championed its role in the Middle Corridor Initiative, serving as a critical bridge linking China to Europe, thereby reinforcing its geopolitical and geo-economic significance in Eurasia. Another testament to Türkiye’s eastward gravitation is its active engagement with the AIIB. As an institution primarily led by China, the AIIB has seen Türkiye emerge as one of its main beneficiaries, funneling considerable funds to support Ankara’s expansive infrastructure projects. Türkiye possesses a 2.54% voting share within the AIIB. Following India and Indonesia, Türkiye has emerged as the third-largest beneficiary of AIIB loans. As of 2019, Türkiye received 11% of the total loans extended by the AIIB. The majority of these funds are allocated to the energy sector. However, despite these efforts, and public statements opposing dollar dominance, Türkiye has achieved limited success in moving away from the dollar.

China’s efforts to promote the RMB on the international stage and challenge the hegemony of the US dollar, he concludes, are multifaceted. It is not just about the currency itself but is deeply tied to China’s broader strategic initiatives and global institutional leadership. In this context, the evolving financial landscape is a clear signal that the dominance of the US dollar is being actively challenged in the context of South-South cooperation, as a “post-hegemonic” form of international cooperation. Certainly, the perceived weaponisation of the dollar and the rise of the developing world as a site of resistance to US hegemony, is hastening this shift, as developing countries collaborate to develop and implement alternatives that insulate them from the economic risks of US policy decisions.

Efe Gürcan’s article is a serious study of a key issue in contemporary international political economy and one that deserves careful study.

The global political economy has long been characterized by the commanding presence of the U.S. dollar—a linchpin that has steadfastly upheld U.S. hegemony across decades. The dollar’s ascendancy, transcending mere economic value, has become emblematic of U.S. strategic influence in both the economic and geopolitical landscapes. However, as we witness the dawn of a new era marked by a multipolar global order, there is growing speculation about the potential waning of the dollar’s omnipotence. This emergence of multiple power centers, each with its own economic and political clout, threatens to reshape the traditional dynamics of international economic relations, challenging the very sanctity of the dollar’s global supremacy.

This article is anchored around the following pivotal inquiries: In what ways is burgeoning multipolarity in the global political economy reshaping perceptions and realities of the U.S. dollar’s dominance? How might a diminished dollar centrality impact the broader edifice of U.S. hegemony and the equilibrium of the global economic order? Which rising powers are at the forefront of this tectonic shift, and what strategic levers are they employing to influence the trajectory?

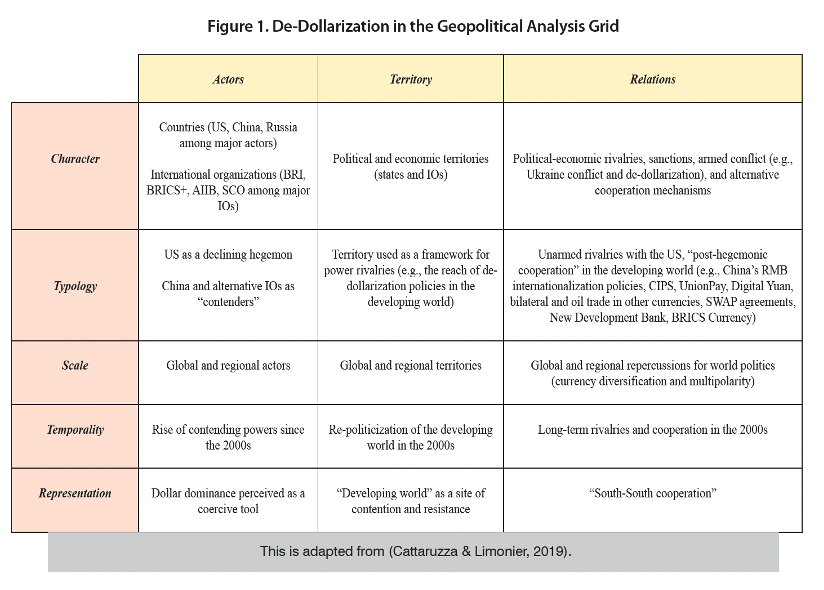

The present study endeavors to illuminate the multifaceted interconnections between a multipolar world and the potential reconfiguration of the dollar’s global standing. With this in mind, it also aims to elucidate the strategic implications for the United States and chart the evolving dynamics that will define the future global economic landscape. Using the method of Geopolitical Analysis Grid (GAG) (Cattaruzza, 2020; Cattaruzza & Limonier, 2019), moreover, this study systematically dissects the strategies and actions of pivotal emerging actors within the multipolar matrix. GAG facilitates a layered exploration of nation-states’ economic postures, geopolitical imperatives, and strategic alignments, all juxtaposed against their unique historical and socio-cultural backdrops. By assimilating these diverse insights, the present article uses this method to forge a holistic perspective on the emergent challenges and opportunities sculpting the global political economy. In this context, the article begins by establishing the conceptual and methodological framework that guides this research. The second and final section delves into an empirical analysis of multipolarization and de-dollarization.

Conceptual and Methodological Framework

To ensure a comprehensive and coherent analysis, it is imperative to commence by establishing a conceptual and methodological framework that will guide our examination of multipolarization and de-dollarization. The notion of U.S. hegemony is pivotal in framing this research. By “hegemony,” I refer to a scenario wherein a single state (or a group of states), “plays a predominant role in organizing, regulating, and stabilizing the global political economy (Du Boff, 2003, p. 1).” Notably, in the aftermath of World War II, U.S. imperialism emerged as the linchpin, driving the imperialist system and positioning itself at the epicenter of global hegemonic relations. It is essential here to clarify that my interpretation of “hegemony” does not necessarily require unanimous consent and unquestioned leadership. It rather encapsulates a nuanced interplay of consent and coercion in varying degrees, serving to relatively stabilize the international order and its alliance system led by a hegemonic power that pretends to act in the general interest, even in the face of discernible dissent (Gürcan, 2022b). For instance, the widely held conviction, prior to the 2000s, that the United States was unparalleled in global leadership—attributed to its economic superiority as a model nation, credibility in global governance, perceived military invulnerability, cultural appeal, and the dominance of the dollar—served as a quintessential illustration of U.S. hegemony.

Another essential term in this context is “multipolarization”, which describes the shift in the global balance of powers, as political, economic, and military clout becomes more evenly distributed, elevating the systemic importance of multiple states (Gürcan, 2019b). In turn, the term “dollar hegemony” describes a situation in which the U.S. dollar is widely adopted as the foremost instrument for international reserves, the main unit of account, and the primary means of payment, achieved through a combination of consensual and coercive measures. “Dollarization” is thereby the result of this hegemony, emerging from a process that entails the use of the U.S. dollar as a reserve of value, a medium of exchange, and a unit of account. Understood as such, one could identify three main types of dollarization. Financial dollarization pertains to the dollarization of assets and liabilities, whereas transaction dollarization relates to the payment system. Price dollarization concerns pricing units for goods and services (Vidal, et. al., 2022; Basosi, 2021; Levy-Yeyati, 2021).

In this context, it is also relevant to briefly address the negative implications of dollarization for the developing world. Adjustments in U.S. monetary policy have frequently precipitated debt, exchange rate, and financial crises in various developing economies. Noteworthy instances include the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, and the 2018 exchange rate crises in Türkiye, Brazil, Argentina, and other economies, sparked by an increase in U.S. dollar interest rates. Broadly speaking, financial systems with high levels of dollarization are often more susceptible to such crises. Therefore, dollarization is typically linked with high and unstable inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, and undisciplined monetary policy. It also heightens the risk of balance sheet and liquidity issues, jeopardizing the financial stability of households, businesses, and financial intermediaries that face currency mismatches. Furthermore, dollarization can negatively impact the real economy, resulting in reduced growth and increased volatility in output (Naceur, Hosny & Hadjian, 2019; Xueying, Dongsheng & Ruiling, 2022; Yang & Ziaojing, 2017). In this scenario, finally, “de-dollarization” refers to the perceived, if not actual, erosion of dollar dominance, as well as “anti-dollar policies [that] successfully reduce reliance on the dollar (McDowell, 2023, p. 5).” Understood as such, one could assume that de-dollarization serves as an important factor that catalyzes the multipolarization of the global political economy, and vice versa.

In the study of phenomena related to multipolarity, such as de-dollarization, the Geopolitical Analysis Grid (GAG) proves invaluable, especially considering the inherent geopolitical character of such processes. Independent of the specific empirical context underpinning multipolarity, GAG’s primary advantage lies in its provision of a systematic approach to geopolitical analysis. Such a structured methodology ensures comprehensive consideration of all pertinent elements, while preventing the omission of significant factors. Additionally, it elucidates the interconnections and influences between different factors, offering a coherent visual representation of intricate data. In this study, GAG assists in delineating the basic parameters of our analysis based on agential, territorial, relational, socio-economic, typological, scalar, temporal, and representational perspectives.

Adapted from Cattaruzza and Limonier’s (2019) framework, the GAG methodology deployed in this study can be broadly delineated into two primary phases. The first phase consists of describing the objects of study, namely the key actors, territories, and relations. Initially, it necessitates the identification of the key actors, which could include states, international organizations, societal groups, and corporate entities. In our case, for example, the main actors include the United States, China, Russia, and a number of international organizations such as BRICS+ (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa+), Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), and the Belt & Road Initiative (BRI), which set the agential parameters of this research. This is followed by an examination of the territories they engage with or invoke, in our case political and economic territories, and a thorough analysis of the relations they maintain, encompassing various cooperation and rivalry dynamics, whether they be political, economic, or cultural (Cattaruzza, 2020; Cattaruzza & Limonier, 2019). The Ukraine conflict, de-dollarization policies, and alternative international cooperation schemes are part of these relations covered in this study. The second phase consists of analyzing the objects of study by setting the necessary analytical parameters. This phase is further compartmentalized into five nuanced sub-steps, focusing on the geopolitical, economic, and cultural dimensions of the previously identified actors, territories, and relations. To begin with, the analysis evaluates the defining character, or the socio-political and economic nature of geopolitical actors, territories, and relations. Concerning the typology element in GAG, it determines whether actors function as aggressors, defenders, contenders, victims, ombudsmen, combatants, or non-combatants, among other types. In our case, the United States stands as a “declining hegemon,” whereas China appears as a “contender state (Desai, 2013).” Furthermore, territories are categorized based on their strategic significance—either as operational arenas, mobilizing frames, or points of contention. In our analysis, for instance, the geography of the developing world emerges as a framework for power rivalries. The typology of relations is also assessed, discerning whether conflicts are overt or latent, armed or unarmed, and symmetrical or asymmetrical (Cattaruzza, 2020; Cattaruzza & Limonier, 2019). While rivalries surrounding de-dollarization are mostly of an unarmed nature, the alternative cooperation mechanisms led by contending states assume a “post-hegemonic” (Gürcan, 2020) character, as will be explored later in greater depth.

The next layer of this phase scrutinizes the spatial magnitude and reach (i.e., scales) of the actors, territories, and relationships under study, emphasizing the scope of the actors’ influence, the expanse of the territories from local to global scales, and the overarching scale of the conflicts in terms of their geopolitical repercussions. In our analysis, the repercussions of multipolarization and de-dollarization attempts are global in scale, leading to a slow pace of currency diversification. Additionally, GAG delves into the temporal dimension, exploring the historical context surrounding the actors, territories, and conflicts. In this case, multipolarization and de-dollarization can be traced back to the early 2000s, which set the temporal parameters of our research. This is complemented by an examination of their symbolic representation—how actors legitimize their stance, the impact of territorial narratives on geopolitical undertakings, and the symbolic representation of the conflicts themselves (Cattaruzza, 2020; Cattaruzza & Limonier, 2019). In the case of multipolarization, our analysis reveals that dollar dominance is increasingly being perceived as a coercive tool by contender states, and the developing world emerges as a site of contention and resistance, which has accelerated the agenda of “South-South cooperation” (Gürcan, 2019b) throughout the 2000s. Figure 1 presents my GAG empirical analysis, which will be discussed in the next section.

Recontextualizing De-Dollarization Within the Geopolitical Grid

The dollar’s international monetary power has been instrumental in forging and maintaining U.S. global hegemony. Following World War II, the United States strategically tethered key sectors of foreign economies to the dollar’s value and stability using tools like international aid, credit assistance, and trade ties. This dominance enabled the United States to effectively issue vast amounts of money with relatively little repercussions, facilitating budget deficits to fund military activities and extend credit, investments, and aid to allies in line with U.S. geopolitical objectives (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023). From a hegemonic point of view, this unique position, termed as “exorbitant privilege” (Cohen, 2012, p. 17), granted the United States increased flexibility in its domestic macroeconomic policy. For many allied nations, defying the U.S.-centric global political economy was not feasible, as alignment with U.S. objectives was often rewarded with access to vital credits and aid. Institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and World Bank further institutionalized dollar dominance (Ciorciari, 2014; Vasudevan, 2021; Yuan, 2018).

Global confidence in the U.S. dollar has been foundational to its dominance. Such confidence has roots in the United States’ past contributions to global production, its unrivalled military prowess, and its capacity to maintain its currency’s purchasing power through technological advancements and a robust service sector. However, recent geopolitical shifts and the multipolarization of world politics appear to be eroding this global confidence (Gürcan 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023). China’s ascent as the leading producer and exporter of high-tech goods, combined with the repercussions of the 2007-2008 financial crisis and U.S. military challenges in countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria, have raised questions about the dollar’s unassailable position. Notably, the U.S. dollar’s share in global reserves has contracted from roughly 70% in 2000 to 58.8% by the second quarter of 2023, among its most modest proportion in the past quarter century (Arslanalp & Simpson-Bell, 2021; Gürcan, 2019b; Yuan, 2018; IMF, 2023).

In 2023, the collapse of three U.S. banks, especially one as influential as Silicon Valley Bank, sent shockwaves across the global financial system. Their downfall was directly tied to the fall in the value of U.S. Treasury securities, a result of sharp interest rate hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve. This situation not only indicates vulnerabilities within the U.S. banking system but also impacts investor confidence in U.S. financial assets. Particularly, the fact that Silicon Valley Bank had invested a significant portion of its deposits in Treasury notes and other quasi-sovereign securities, whose values plummeted due to interest rate hikes, shows the risks associated with excessive reliance on U.S.-denominated assets. As these assets lost value, especially given the weaker state of the U.S. dollar, it underscored the potential pitfalls of depending too heavily on the dollar and U.S. financial instruments (Caudevilla, 2023).

Daniel McDowell (2023) highlights that U.S. foreign policy and its strategic use of the dollar have increasingly been perceived as a political risk on a global scale. This perception is fostering a growing desire among global governments to lessen their reliance on the dollar, due to concerns about susceptibility to U.S. influence. McDowell (2023) goes on to emphasize that sanctions are a crucial tool in this strategic use of the dollar to counter the emerging powers threatening U.S. hegemony. Primary sanctions aim to directly isolate the targeted individual, company, or government from the dollar-based financial system. In turn, secondary sanctions are designed to exclude the target from global financial networks through the involvement of foreign financial institutions. According to McDowell (2023), the frequency of the United States’ strategic use of the dollar has been on the rise. Particularly under the Obama and Trump administrations, financial sanctions became a common tool. The number of sanctions-related Executive Orders (SREOs) saw a significant increase, growing by approximately 500 percent from 22 in 2000 to 94 by the end of 2020. While some of these orders are specifically directed at non-state entities not directly connected to foreign governments, such as those involved in counter-narcotics trafficking or counter-terrorism efforts, the majority of sanctions programs are state-targeted. The United States applies pressure by blacklisting individuals and entities close to a regime or directly targeting government officials and state institutions (McDowell, 2023).

The ramifications of declining global confidence in the U.S. dollar and the growing threat perception coming from the U.S. sanctions are particularly visible in the developing world. A strong case in point is Latin America. Relative to other global regions, Latin America has historically exhibited a high level of reliance on the U.S. dollar. However, a shift towards decreasing this dependence, known as de-dollarization, is becoming apparent in several key Latin American nations, including Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Venezuela. Nonetheless, the pace of reducing dollarization in these countries is expected to be gradual, as evidenced by the experience of Peru. The strategies employed by most Latin American countries in de-dollarizing involve gradual, incentive-based approaches. This being said, Argentina has seen a marked decrease in the dollarization of its banking sector, and Brazil has experienced a considerable reduction in public debt tied to the dollar. Perhaps a more striking example of this trend is Bolivia, which until the mid-2000s, was one of the most dollarized countries globally.

In 2002, Bolivia’s rate of deposit dollarization was over 93%. However, the implementation of left-wing policies, coupled with macroeconomic stability, has led to one of the most significant de-dollarization efforts, both regionally and globally. By 2019, the proportion of deposits in foreign currencies had dramatically fallen to just 13.8% in Bolivia. By moving away from a dollar-centric economy, Bolivia has lessened its vulnerability to external shocks that affect the U.S. dollar, thereby diversifying its economic base (Sharma, 2023; Quenan & Edgardo, 2007; Levy-Yeyati, 2021).

This trend emerged against the backdrop of the unprecedented rise of the Latin American left in the 2000s as an important catalyst in multipolarization, which also includes Lula’s Brazil, a leading BRICS+ member (Gürcan, 2019b). At this point, one should highlight that the multipolarization of the global political economy goes hand in hand with the rise of South-South cooperation, embodied not only in the rise of the Latin American left and its social justice-oriented regionalism, but also in the proliferation of Eurasia’s security-oriented regionalism, including the SCO, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and other cooperation schemes such as the BRICS+, BRI, and the AIIB (Gürcan, 2019b, 2019a, 2020). These organizations hold the potential to serve as conduits for de-dollarization in forthcoming years.

Recently, the announcement by Saudi Arabia’s finance minister at the 2023 World Economic Forum was monumental. Saudi Arabia has had a longstanding relationship with the U.S. dollar, particularly in the context of oil trade. This relationship, often referred to as the “petrodollar” system, has been a cornerstone of dollar dominance for nearly half a century. Saudi Arabia’s declared openness to trading in other currencies signals a potential shift in the global energy trade, which has historically been a significant factor bolstering the U.S. dollar’s global standing. This adds to the push by Chinese President Xi Jinping for Gulf countries to accept the RMB for oil trade, which is indicative of China’s strategic efforts to internationalize its currency and challenge the U.S. dollar’s dominance. If Saudi Arabia and potentially other Gulf countries start trading oil in yuan or other currencies, this would significantly erode the dollar’s dominant position in global energy markets (Caudevilla, 2023).

Additionally, the March 2023 agreement between Chinese and French energy companies to settle an LNG deal in yuan is also of historic importance. Such a transaction in a currency other than the U.S. dollar is a clear signal of diversification away from dollar-denominated trade, especially in the vital energy sector. Given the magnitude and importance of energy deals, conducting transactions in currencies other than the dollar could set a precedent for future trade agreements. Equally important is China’s recent move to use the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange as a platform for yuan settlements with Arab Gulf nations and a strategic effort to bypass the U.S. dollar in energy trade. Given the vast volumes of oil and gas traded between the Gulf and China, this shift could have a significant impact on the demand for the U.S. dollar in global energy markets. A similar situation goes for nuclear energy. The 2023 agreement between Bangladesh and Russia to use the Renminbi for the settlement of a nuclear plant transaction is yet another sign of countries seeking alternatives to the U.S. dollar for significant infrastructure and development projects. It is particularly notable that Russia, a country traditionally involved in dollar-denominated energy transactions, is open to using the RMB in such a substantial deal (Sharma, 2023).

In this evolving landscape, therefore, China is seizing the opportunity to amplify its global financial footprint. In fact, China’s push to reform the dollar-centric global financial system began following the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Dai Xianglong, who was then the Governor of the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), expressed in 1999 that the instability caused by the dominant role of a few national currencies as international reserve currencies, as well as the system’s failure to address balance of payments imbalances, leads to international financial crises. In the wake of the 2007–2008 global financial crisis, Zhou Xiaochuan, Dai’s successor, emphasized the need to overhaul the international monetary system. He proposed an international reserve currency that would be independent of individual nations, and identified the weakening dollar as a key factor in the global economic crisis. This environment spurred discussions on China’s capacity to establish a yuan-based trading framework through initiatives like the Belt Road Initiative and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Importantly, countries participating in the Belt Road Initiative have increasingly accepted the RMB in trade with China. Moreover, in April 2023, Argentina began using yuan instead of U.S. dollars for Chinese imports. Brazil and China also agreed to conduct trade and financial transactions using their respective currencies. Additionally, the concept of “Petroyuan” has been gaining increasing attention for its potential to challenge the U.S. dollar’s dominance in global oil trade, moving towards multipolarity.

China’s oil contracts with Russia are predominantly yuan-denominated, and countries like Iran, Iraq, Venezuela, and Indonesia also engage in similar practices in their dealings with China and Russia. Following the 2018 BRICS Summit, China introduced yuan-denominated oil futures on the Shanghai International Energy Exchange. These futures, priced in renminbi, can also be converted into gold at the Shanghai and Hong Kong Gold Exchanges. This development allows China, as the world’s largest oil importer, to trade oil domestically using gold, enabling suppliers to convert their renminbi payments into gold immediately. While the Shanghai-traded yuan oil futures still trail behind the London-traded Brent and New York-traded WTI futures in volume, they have outperformed similar products in Tokyo and Dubai. A significant milestone in this regard was reached in 2023 when China and Saudi Arabia agreed to trade oil using yuan, known as the “petro-yuan” deal. Other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are also considering the adoption of the yuan (Zongyuan & Papa, 2022; Siddiqui, 2023; Soni & Jain, 2023; Gouvea & Gutierrez, 2023).

In this context, China emerged as a “contender state (Desai, 2013),” one that has “the material capabilities for competing for dominance in a system (Keersmaeker, 2017, p. 25)” and “the potential to foster global political change by promoting and expanding [its] own projects (Gürcan, 2019b, p. 6).” China’s endevors as a contender state are evident in its vast holdings of U.S. treasury bonds, the emergence of cities like Shanghai as global financial hubs, the magnitude of China’s sovereign wealth funds and the rapid increase in Chinese direct investments, development support, and credit outflows (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Kokubun, 2003). By internationalizing the RMB, China is actively contributing to the ongoing process of de-dollarization, challenging the long-standing U.S. financial hegemony. The internationalization of the Chinese RMB, particularly following the 2007-2008 U.S. financial crisis, has emerged as a potent force challenging the established dominance of the U.S. dollar in global economic structures. The global scale of this crisis cast a shadow on the prevailing U.S. hegemony (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023). It was against this transformative backdrop that the year 2009 saw the Chinese authorities enact a series of pivotal measures. They sanctioned offshore renminbi bank accounts, initially in Hong Kong, which subsequently expanded to other jurisdictions. Renminbi bonds began to be issued in Hong Kong. The renminbi was employed more frequently to invoice and settle international trade transactions. Swap lines were established between the People’s Bank of China and various other central banks (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Kroeber, 2018).

By 2015, the RMB’s growing significance was recognized by its inclusion in the International Monetary Fund’s reserve currency basket, positioning it among the world’s top five currencies. Its ascent can further be gauged by its rising share in global currency reserves, peaking at 2.76% by the third quarter of 2022. Even with these gains, the RMB, being the fifth most active currency in global payments, still remains eclipsed by the U.S. dollar’s dominant 41.38% share (RMB Tracker Document Centre, 2022). As Kroeber (2018) rightly states, while the RMB’s progress is laudable, it is yet to pose a definitive challenge to globally dominant currencies.

A significant development in RMB’s journey of internationalization is the institution of the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), envisioned as an alternative to the dollar-centric SWIFT. Established in 2015, CIPS recorded transactions worth 5.7 trillion yuan in its inaugural second quarter, a figure that astonishingly climbed to 12.14 trillion yuan by the third quarter of 2020, marking approximately a 113% growth (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Borst, 2016). Furthermore, by 2018, 60% of CIPS transactions were conducted in currencies other than the U.S. dollar (Kida et al., 2019). While still trailing SWIFT, CIPS’s increasing share is undeniable, further punctuated by the RMB’s fifth rank in SWIFT transactions, coming after established giants like the U.S. dollar, the Euro, the British Pound, and the Japanese Yen (Barton, 2021). However, while CIPS embodies the potential to counterbalance global dollar supremacy, its current dependency on the SWIFT messaging system for transacting with banks outside China remains a palpable vulnerability. But as Eichengreen (2022) articulates, its prospects in disrupting the weaponization of SWIFT by the United States cannot be understated.

It is worthwhile to underline that, in March 2023, RMB overtook dollar to become the most-used currency in China’s cross-border transactions, which corresponded to 48.4% of all settlements (Reuters, 2023; Sharma 2023). China’s endeavors to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar and bolster the international stature of its currency, the RMB, have involved strategic maneuvers in global financial diplomacy. An integral part of this strategy has been the establishment of currency swap agreements with developing nations. By 2017, China had entered into swap agreements that amounted to more than $500 billion with 35 countries (Heep, 2014; Plubell & Siyao, 2017). This momentum did not wane; by 2020, China expanded its bilateral swap agreement (BSA) portfolio to include 41 countries, with a cumulative value surpassing RMB 3.5 trillion (equivalent to $554 billion) (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Tran, 2022).

In parallel with the multipolarization of the international political economy, the global landscape of bilateral swap lines (BSLs) underwent a marked transformation during this period. From a mere handful in 2007, the count escalated to 91 by the end of 2020, which was triggered by the “Great Recession” as a milestone in the relative decline of U.S. financial hegemony (Perks et al., 2021).

While, at a cursory glance, this proliferation of BSLs might not exclusively highlight China’s burgeoning financial influence, it would be relevant to interpret it within the framework of China’s “financial statecraft” philosophy. As elucidated by McDowell (2023), this approach aligns national financial and monetary interests with the pursuit of foreign policy objectives. Financial statecraft, as conceptualized by Armijo and Katada (2015), encompasses the deliberate deployment by national governments of their domestic or global financial assets to realize persistent foreign policy targets, be they political, economic, or financial in nature. In China’s case, the surge in its BSLs, alongside its growing volume of bilateral trade, signifies a reciprocal relationship, mutually enhancing each other. Such a relationship forms a cornerstone of China’s financial statecraft model (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Lin et al., 2016; Song & Xia, 2020; Zhang et al., 2017).

China’s proactive steps towards de-dollarization and establishing the RMB as an international currency have manifested in various other innovative financial undertakings. Initiated in 2002, China’s UnionPay credit card system was instituted as a competitor to globally renowned credit card giants, Visa and MasterCard. By 2019, UnionPay’s ascendancy in the global credit card market was evident, as it held the lion’s share, accounting for 45% of credit cards in circulation. This significant development is not merely about market competition. It represents a strategic move to offer an alternative financial lifeline to nations, such as Russia, Iran, and Cuba, which, due to Western sanctions, find themselves estranged from the dominant international payment systems (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Finextra Research, 2019; Russell, 2015; Slawotsky, 2020).

Another pivotal milestone in China’s financial blueprint is the creation of the Digital Yuan. Sanctioned by the State Council in 2017, the digital currency initiative has made significant strides. According to the 2021 PwC Global Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) Index, China holds the distinguished third position among countries with robust and advanced CBDC projects, only behind the Bahamas and Cambodia. The momentum behind the Digital Yuan’s trial phases has been noteworthy, with the total value in circulation nearing 14 billion by the end of 2022, as disclosed by the People’s Bank of China (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; The State Council of the & People’s Republic of China, 2023).

The advantages of the Digital Yuan are manifold. Beyond expediting financial transactions, the use of this blockchain-driven technology enhances China’s capability for comprehensive financial oversight and synchronization—key attributes for maintaining a robust economy (Kshetri, 2023). Moreover, the Digital Yuan could present an avenue for other nations to sidestep the constraints of Western sanctions. Furthermore, China’s foothold in the realm of Artificial Intelligence can be solidified by this initiative, and it could pave the way for the global proliferation of China’s mobile payment systems. The overarching consequence of these endeavors might be China’s transformation into a global pacesetter in both financial and technological domains, enabling it to set international norms and standards (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023; Slawotsky, 2020).

China’s push for de-dollarization and internationalizing the RMB is not just through direct financial means but is deeply intertwined with its strategic institutional initiatives and leadership in the global arena. In this regard, China’s institutional leadership has been progressively positioning itself as an “agenda-setter” and “norm-maker” in the global landscape. Rather than merely being a participant in global governance, China aims to be at the forefront, steering dialogues and framing norms. This proactive role gives China the ability to influence international practices in ways that can favor the RMB. Moreover, the fact that many international actors willingly participate in China-led initiatives is indicative of the perception of these initiatives being inclusive and comprehensive. Such widespread engagement not only lends credibility to these initiatives but also amplifies their reach and impact, paving the way for broader acceptance of Chinese financial instruments, including the RMB (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023).

The BRI stands out as one of China’s most ambitious global projects. While the initiative primarily focuses on infrastructural development and connectivity across continents, it also carries significant financial implications. By financing projects within the BRI framework, China can encourage or even mandate the use of yuan for transactional purposes, thereby promoting its global usage. If the BRI projects are primarily transacted in yuan, it could lead to an increased demand for the currency, thereby internationalizing it and challenging the dominance of the US dollar (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023).

Relatedly, the establishment of the AIIB, under China’s initiative, has been another critical move in reshaping the global financial landscape. Positioned as the world’s first multilateral development bank dedicated solely to infrastructure the AIIB, headquartered in Beijing, exemplifies China’s strategic use of institutional mechanisms to further its financial ambitions (Wilson, 2017). By leading and guiding investments through the AIIB, China gets a platform to promote the RMB in international finance, especially in large-scale infrastructure projects across the Asian continent (Gürcan, 2022a; Gürcan & Donduran, 2023).

Similarly, the decision by members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) at the 2022 summit in Uzbekistan to advance their agenda for expanding trade in local currencies can be viewed as a strategic move that further undermines global confidence in the U.S. dollar. The SCO is not just any regional organization. It comprises major economies, such as China and Russia, and together its member states account for a substantial portion of the world’s population and GDP.

Decisions made by the SCO, therefore, have considerable weight and can influence broader economic trends. Given that China is a leading member of the SCO and has been actively pushing for the internationalization of its currency, such a move by the SCO can accelerate this process, further positioning the RMB as an alternative to the dollar in regional trade (Zongyuan, 2022).

The institutional dynamics of de-dollarization also extend to the BRICS+. The BRICS’s New Development Bank (NDB) has actively engaged in several initiatives, including the establishment of lending programs using local currencies. Moreover, it has set up bond programs that are registered in BRICS nations. Significantly, the NDB has emerged as the foremost issuer in the official sector of Panda bonds, which are bonds denominated in renminbi and issued in China by entities from outside the country (Zongyuan & Papa, 2022).

Importantly, the use of the dollar as a tool for sanctions and other punitive measures increasingly alienates several countries and prompts them to look for alternatives, fearing the economic repercussions of U.S. policy decisions. Such concerns have been magnified after recent events, such as the current Ukraine conflict. Against this backdrop, the 2023 BRICS Summit witnessed a significant expansion, with six new members joining the bloc, thus forming the BRICS+ (Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates). This expanded group would control a substantial share of the global GDP and population, which corresponds to at least 30% of the global GDP and 46.5% of the global population. Moreover, the BRICS’ current debate about creating a common BRICS currency could be seen as a direct response to the challenges of dollar dependency. While the technical and software groundwork for a new BRICS currency is reportedly ready, its launch requires the political agreement of member countries. The support from three member heads of state indicates growing momentum for this initiative. Furthermore, with the inclusion of major oil-producing countries, the BRICS+’s share of global oil production would surge to 43.1%. If these countries decide to accept alternative currencies for oil trading, it can dramatically diminish the dollar’s role in the global oil market. Additionally, the New Development Bank’s three-year plan for de-dollarization and increased lending in local currencies demonstrates the BRICS’ commitment to reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar. Their achievements in financial cooperation, such as the New Development Bank (NDB) and Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), further this agenda. This environment also shapes central bank policies and bilateral trade relations within the BRICS+. Particularly, BRICS central banks, such as the Bank of Russia, have been actively diversifying their reserve assets, minimizing their holdings in U.S. Treasury securities in favor of assets like gold. Additionally, the substantial decline in the use of the U.S. dollar for bilateral trade settlements between Russia and China over five years indicates a growing preference for local currencies. The BRICS’ development of cross-border payment mechanisms, like the BRICS Pay system and alternatives to the SWIFT network, also suggests a desire to decrease dependence on U.S.-dominated financial structures. The increasing acceptance of UnionPay across BRICS countries also supports this direction (Ifimes, 2023; Kumar, 2023; Liu & Papa, 2022; Ramos, 2023; Steinbock, 2023; teleSUR, 2023).

It is possible to argue that China’s efforts to internationalize the RMB and its pioneering role in institutional settings, notwithstanding the enduring dominance of the U.S. dollar, underscores the post-hegemonic nature of de-dollarization. Presently, de-dollarization represents a nascent trend, predominantly evident in developing nations seeking to diversify their monetary assets. In this context, the notion of “post-hegemony” encompasses not only the relative waning of U.S. global influence and the rise of alternative power hubs, but also the burgeoning South-South collaboration. Additionally, it reflects myriad complexities and contradictions that arise as various actors strive to eclipse the United States, all while navigating substantial economic, military, and geopolitical hurdles (Gürcan, 2020).

Amidst the combined acceleration of multipolarity and de-dollarization, there has been a notable rise in central banks’ acquisition of gold worldwide. Currently, central banks account for approximately one-third of the global annual demand for gold, a level not seen since the 1950s. This trend was catalyzed significantly by the Great Recession and the consequent decline in the United States’ financial dominance. The reserves of monetary gold held by central banks had decreased throughout the 1990s and 2000s. However, the 2008 global financial crisis reignited central banks’ interest in gold as a valuable financial asset. This international trend of accumulating gold was predominantly observed in 49 countries that reported increases in their monetary gold reserves during these years, with Russia, Türkiye, and China being notable examples. Venezuela, facing heavy sanctions and thus isolated from the dollar system, was not alone in turning to gold. Iran, also cut off from using SWIFT messaging for oil and banking transactions, reportedly began accepting physical gold as payment for oil exports to Türkiye. In a significant move, China, in July 2015, ended years of non-disclosure about its gold reserves, revealing that it had acquired 604 tons of gold since 2009, a volume second only to Russia’s acquisitions. This purchase marked an almost 60 percent increase in China’s reserves since 2009, making it the world’s fifth-largest holder of gold, surpassing Russia. Additionally, China is recognized as the world’s largest consumer and second largest importer of gold (Siddiqui, 2023; McDowell, 2023; Lan, 2017).

Following the 2014 Ukraine crisis, Western governments imposed sanctions on Russia across various sectors. In retaliation, particularly against the sanctions targeting its financial payment system by the United States and Europe, Russia initiated the Bank of Russia Financial Message Transmission System (SPFS) in 2014. By September 2022, 440 banking clients worldwide had gained access to the SPFS. Another notable shift occurred in the fourth quarter of 2020 when U.S. dollar-denominated exports from Russia dropped by over 50% for the first time. On April 1, 2022, Russia implemented the “Ruble Settlement Order.” This regulation stipulated that Western European countries wishing to purchase natural gas must open a ruble account at the Russian Natural Gas Industrial Bank to deposit foreign currencies. Additionally, between March and May 2018, there was a noticeable decrease in the value of U.S. Treasury bills held by Russia, marking another significant milestone in its financial strategy. By 2020, approximately 30 percent of Russian reserves were in U.S. dollars, but only 10 percent were held within the United States. The proportion of dollar-denominated debts in both corporate and public sectors in Russia had peaked at about 70 percent in the fourth quarter of 2015, before gradually declining. By 2020, the dollar’s share in Russian corporate debt had reduced to around 50 percent, indicating a significant decrease. A significant achievement was reached by the fourth quarter of 2020, when the proportion of Russian exports conducted in U.S. dollars dropped below 50 percent for the first time. At the BRICS country level, furthermore, Russia has been the most successful in reducing its reliance on the U.S. dollar in international trade since 2013 (Yan, 2023; Zongyuan & Papa, 2022; McDowell, 2023).

One should emphasize that the sanctions imposed on Russia have inadvertently facilitated the internationalization of the Chinese Renminbi. In 2015, a significant development occurred when the state-owned China Development Bank established a 6 billion renminbi credit line with two major Russian banks, Sberbank and VTB Group. Between the first and second quarters of 2018, Russia’s Central Bank reduced its dollar holdings by over 10 percent while simultaneously increasing its RMB holdings by a similar margin.

In early 2019, Russia’s central bank significantly invested in the renminbi, boosting its share in Russia’s foreign exchange reserves from 5 percent to 15 percent. Moreover, Gazprom Neft, Russia’s third-largest oil producer and a subsidiary of the state-owned Gazprom, has been selling oil to China in exchange for yuan since early 2015. The monetary connections between Russia and China have expanded in other areas as well. For instance, VTB, Russia’s second-largest bank, reached an agreement with the Bank of China to conduct transactions in their respective local currencies. Both countries have also declared their intention to bypass the U.S. dollar in bilateral trades, opting instead for their own currencies. The collaboration between Russian and Chinese banks has been growing. China’s state-owned Import Export Bank has agreed to assist Russian banks cut off from Western capital markets due to Western sanctions. Particularly crucial are the Sino-Russian gas deals, which involve the world’s largest energy importer, China, and the largest energy producer, Russia, potentially challenging the global dominance of the U.S. dollar as the primary petro-currency. Between 2014 and 2018, Russia and China managed to reduce the dollar’s role in their bilateral trade by over 20 percent. By the end of 2020, at least twenty-three Russian banks had joined the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), China’s alternative to the SWIFT payment system (Lan, 2017; McDowell, 2023; Zongyuan & Papa, 2022).

Finally, a few words are in order regarding Türkiye. In contemporary geopolitics, Türkiye occupies a unique and often paradoxical position. Historically aligned with Western interests, Türkiye has been a strategic member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and has traditionally been considered a close ally of the United States. However, the bilateral relations between Ankara and Washington have undergone notable strains since the 2010s. The two countries found themselves at odds over several issues, including the U.S. sanctions against Iran and the role of Kurdish forces in the Syrian conflict. Relations worsened following a failed coup attempt in 2016 aimed at ousting President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who then openly accused the United States of supporting the coup plotters. This strained relationship reached a nadir in 2017 when the United States threatened Türkiye with financial sanctions, ultimately imposing punitive measures in late 2018. These actions deeply affected U.S.-Turkish relations and prompted Türkiye to seek alternatives to its dependence on the U.S. dollar (Gürcan, 2020, p. 128; McDowell, 2023). Since 2018, Türkiye has faced a series of sanctions imposed by the United States, creating significant tension within the Western alliance (New York Times, 2018; Sharp, 2023).

Parallel to these developments, Türkiye has articulated on multiple occasions its interest in deepening ties with non-Western multilateral organizations. Ankara has repeatedly signaled its intention to explore membership possibilities within the SCO and BRICS – two prominent platforms that present alternatives to the Western-centric global order (e.g., Reuters, 2022; TASS, 2018). Furthermore, Türkiye’s engagement with the BRI is noteworthy. Within the BRI framework, Türkiye has championed its role in the Middle Corridor Initiative, serving as a critical bridge linking China to Europe, thereby reinforcing its geopolitical and geo-economic significance in Eurasia (Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs, n.d.). Another testament to Türkiye’s eastward gravitation is its active engagement with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). As an institution primarily led by China, the AIIB has seen Türkiye emerge as one of its main beneficiaries, funneling considerable funds to support Ankara’s expansive infrastructure projects. Türkiye possesses a 2.54% voting share within the AIIB. Following India and Indonesia, Türkiye has emerged as the third-largest beneficiary of AIIB loans. As of 2019, Türkiye received 11% of the total loans extended by the AIIB. The majority of these funds are predominantly allocated to the energy sector (Gürcan, 2022a, p. 613).

In a move similar to Russia, Türkiye’s central bank significantly increased its gold reserves in response to the escalating U.S. sanctions. After maintaining gold reserves of around 100 metric tons from 2000 to 2016, Türkiye became the second-largest national purchaser of gold in 2017, trailing only Russia. Moreover, Türkiye not only augmented its gold reserves but also relocated them. In early 2018, amidst looming U.S. sanctions, it was reported that Türkiye had transferred approximately $220 billion in gold from the New York Federal Reserve back to its own territory (McDowell, 2023). In 2022, Türkiye ranked as the world’s fifth-largest gold importer, trailing only Switzerland, China, the UK, and India. By the second quarter of 2023, Türkiye has ascended into the top ten nations in terms of gold reserves (Statista, 2022; 2023).

Besides these gold policies, Türkiye also engaged in swap agreements. For instance, in October 2017, the TCMB, Türkiye’s Central Bank entered into a local currency swap arrangement with Iran. This move aligned Ankara’s de-dollarization interests with Tehran, which was also under U.S. sanctions. Subsequently, the TCMB signed a local currency swap deal with Qatar, right after the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) imposed Magnitsky sanctions on two Turkish officials. Following this development, Turkish authorities established a local currency trade agreement with Russia and Iran, committing to reduce reliance on the dollar in trading petroleum, natural gas, and other commodities. In October 2019, Türkiye and Russia formalized an agreement to use the ruble and lira in cross-border transactions and to utilize the Russian messaging system instead of SWIFT (McDowell, 2023). By 2022, the cumulative value of these agreements reached an impressive $28 billion. These swap arrangements have been established with a diverse array of countries including China, Qatar, South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and Azerbaijan (Soylu, 2022). Such initiatives underline Türkiye’s commitment to diversifying its economic dependencies and mitigating potential financial vulnerabilities. Despite these efforts and public statements opposing dollar dominance, however, Türkiye achieved limited success in moving away from the dollar. Data following the U.S. sanction threats in 2017 and the actual sanctions in 2018 do not show a significant shift in Türkiye’s trade practices away from the dollar (McDowell, 2023).

Conclusion

Seen from the GAG framework, the combined impact of the U.S. banking crises, the weakening position of the U.S. dollar, and major global players like Saudi Arabia considering alternatives to the U.S. dollar contribute to the broader trend of de-dollarization. The term “de-dollarization” refers to a global movement towards reducing reliance on the U.S. dollar in international trade and finance, which encourages several countries and businesses to diversify their currency holdings and trading practices, potentially diminishing the dollar’s dominant role. This process cannot be conceived outside the context of the multipolarization of the global political economy, which gained steam in the 2000s. Particularly, China, the main contender of U.S. hegemony, emerged as the leading agent of de-dollarization. Its efforts over the last decade signify an unmistakable stride toward RMB internationalization, positioning itself as a noteworthy contender in the evolving dynamics of global finance. Despite the persisting supremacy of the U.S. dollar, the expansion in the count and value of China’s national currency mirrors China’s unwavering commitment to expand its global footprint, attain enhanced financial influence, and assert its position in global economic dynamics.

China’s efforts to promote the RMB on the international stage and challenge the hegemony of the U.S. dollar are multifaceted. It is not just about the currency itself but is deeply tied to China’s broader strategic initiatives and global institutional leadership. By spearheading and driving global projects and institutions, China indirectly creates pathways and platforms for the RMB’s increased acceptance and utilization worldwide. In this context, the evolving financial landscape, driven by actions of the BRICS+, BRI, SCO, and AIIB, as well as the proliferation of BSLs, and the rise of Digital Yuan, UnionPay, CIPS, and energy trade in other currencies, is a clear signal that the dominance of the U.S. dollar is being actively challenged in the context of South-South cooperation, as a “post-hegemonic” form of international cooperation. Certainly, the perceived weaponization of the dollar and the rise of the developing world as a site of resistance to U.S. hegemony, is hastening this shift, as developing countries collaborate to develop and implement alternatives that insulate them from the economic risks of U.S. policy decisions.

Regarding the case of Türkiye, finally, its multifaceted foreign policy endeavors to balance the Western powers with emerging partnerships in the East. Importantly, the overarching dominance of the U.S. dollar in global financial systems continues to pose an existential threat to the Turkish economy. Yet, through proactive financial diplomacy, as evidenced by its extensive swap agreements, Türkiye seeks to navigate these challenges with increasing adeptness, indirectly contributing to de-dollarization within the context of growing multipolarity.

Overall, one could conclude that efforts to reduce reliance on the U.S. dollar hold significant symbolic value, yet they remain somewhat limited and incomplete. There is a noticeable, albeit gradual, reduction in the dominance of the U.S. dollar. The International Monetary Fund has recently noted a slow decrease in the dollar’s role within international bank reserves, indicating a weakening of its hegemonic status. Progress has been made in diminishing the dollar’s dominance, as seen in the diversification of foreign exchange reserves and in conducting trade using currencies other than the dollar. This shift is reflected in the reduced proportion of the dollar in allocated foreign exchange reserves and an increase in trade transactions using alternative currencies. The most significant change observed is in the dollar’s share of foreign exchange reserves. While there has not been a sudden, major shift, there is steady advancement in the broader use of the Chinese Renminbi, which is evolving from a minor to a major strong currency. However, in areas that require extensive financial markets and networks, like foreign exchange transactions, debt issuance, and payment clearing, the dollar still retains its dominant position. To reshape the global financial system, the BRICS+ nations should persist in leading the charge towards lessening global dependence on the dollar (Siddiqui, 2023; Rana & Chan, 2022; Li, 2023; Chan & Mingjiang, 2022).

References

Armijo, L. E., & Katada, S. N. (2015). Theorizing the Financial Statecraft of Emerging Powers. New Political Economy, 20(1), 42–62.

Arslanalp, S., & Simpson-Bell, C. (2021). US Dollar Share of Global Foreign Exchange Reserves Drops to 25-Year Low. IMF Blog. https://blogs.imf.org/2021/ 05/05/us-dollar-share-of-global-foreign-exchange-reserves-drops-to-25-year-low

Barton, S. (2021). Yuan’s Popularity for Global Payments Hits Five-Year High. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-02-18/yuan-spopularity- for-cross-border-payments-hits-five-year-high

Basosi, D. (2021). Dollar Hegemony. In I. Ness & Z. Cope (Eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism (pp. 113–130). Palgrave Macmillan.

Borst, N. (2016). CIPS and the International Role of the Renminbi. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. https://www.frbsf.org/banking/asia-program/pacific-exchangeblog/ cips-and-the-international-role-of-the-renminbi

Cattaruzza, A. (2020). Defence studies and geographic methodology: From the practical to the critical approach. In D. Deschaux-Dutard (Ed.), Research Methods in Defence Studies: A Multidisciplinary Overview (pp. 15–30). Routledge.

Cattaruzza, A., & Limonier, K. (2019). Introduction à la géopolitique. Armand Colin.

Caudevilla, O. (2023). What role can the digital yuan play in de-dollarization? Asia News Network. https://asianews.network/what-role-can-the-digital-yuan-play-in-de-dollarization

Chan, E. & Mingjiang, L. (2022). Renminbi Internationalisation and US Dollar Hegemony. RSIS Commentary, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, N. 120.

Ciorciari, J. D. (2014). China’s Structural Power Deficit and Influence Gap in the Monetary Policy Arena. Asian Survey, 54(5), 869–893.

Cohen, B. J. (2012). The Benefits and Costs of an International Currency: Getting the Calculus Right. Open Economies Review, 23(1), 13–31.

Desai, R. (2013). Geopolitical economy: After US hegemony, globalization and empire. Pluto Press ; Distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan.

Du Boff, R. B. (2003). US hegemony: Continuing decline, enduring danger. Monthly Review, 557, 1–15.

Eichengreen, B. (2022). What Money Can’t Buy: The Limits of Economic Power. Foreign Affairs, 101, 64–73.

Finextra Research. (2019). China’s growth cements UnionPay as world’s largest card scheme. https://www.finextra.com/pressarticle/80435/chinas-growth-cements-unionpay-as-worlds-largest-card-scheme

Gouvea, R. & Gutierrez, M. (2023). De-Dollarization: The Harbinger of a New Globalization

Architecture?. Theoretical Economics Letters, 13(4), 791–807.

Gürcan, E. C. (2019a). Geopolitical Economy of Post-hegemonic Regionalism in Latin America and Eurasia. In P. Zarembka (Ed.), Class history and class practices in the periphery of capitalism (pp. 59–86). Emerald Publishing.

Gürcan, E. C. (2019b). Multipolarization, South-South Cooperation and the Rise of Post-Hegemonic Governance. Routledge.

Gürcan, E. C. (2020). The construction of “post-hegemonic multipolarity” in Eurasia: A comparative perspective. The Japanese Political Economy, 46(2–3), 127–151.

Gürcan, E. C. (2022a). Çin’in Finansal Hegemonyasının Yükselişi. In M. H. Caşın, S. Kısacık, & C. Donduran (Eds.), 21. Yüzyılda Bütün Boyutlarıyla Çin Halk Cumhuriyeti (pp. 598–618). Nobel Akademik.

Gürcan, E. C. (2022b). Imperialism after the neoliberal turn. Routledge.

Gürcan, E. C., & Donduran, C. (2023). The economic and institutional dynamics of China’s growing financial influence: A “structural power” perspective. The Japanese Political Economy, 49(1), 109–135.

Heep, S. (2014). China in global finance: Domestic financial repression and international financial power. Springer.

Ifimes. (2023). 2023 World: BRICS – De-dollarization Summit. https://www.ifimes.org/en/researches/2023-world-brics-de-dollarization-summit/5205

IMF. (2023). Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves. https://data.imf.org/?sk=e6a5f467-c14b-4aa8-9f6d-5a09ec4e62a4

Keersmaeker, G. de. (2017). Polarity, balance of power and international relations theory: Post-Cold war and the 19th century compared. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kida, K., Kubota, M., & Cho, Y. (2019). Rise of the Yuan: China-Based Payment Settlements Jump 80%. https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/ Markets/Rise-of-the-yuan-China-based-payment-settlements-jump-80

Kokubun, R. (2003). China and Japan in the Age of Globalization. Japanese Economy, 31(3–4), 108–119.

Kroeber, A. (2018). China as a Global Financial Power. In W. Wu & M. W. Frazier (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Contemporary China (pp. 447–458). Sage.

Kshetri, N. (2023). China’s Digital Yuan: Motivations of the Chinese Government and Potential Global Effects. Journal of Contemporary China, 32(139), 87–105.

Kumar, R. (2023). BRICS: 15th Summit and Beyond. https://www.idsa.in/issuebrief/BRICS-15th-Summit-and-Beyond-RKumar-280823#:~:text=The%20event%20gained%20exceptional%20significance,new%20members%20of%20the%20group

Lan, C. (2017). Currency Wars and the Erosion of Dollar Hegemony. Michigan Journal of

International Law, 38(1), 57–119.

Levy-Yeyati, E. (2021). Financial dollarization and de-dollarization in the new millennium. Latin American Reserve, Working Paper Series, January.

Li, Yuefen. (2023). Trends, reasons and prospects of de-dollarization. South Center, Working Paper Series, No. 181, Geneva.

Lin, Z., Zhan, W., & Cheung, Y. (2016). China’s Bilateral Currency Swap Lines. China & World Economy, 24(6), 19–42.

Liu, Z. Z., & Papa, M. (2022). Can BRICS De-dollarize the Global Financial System? (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

McDowell, D. (2023). Bucking the buck: US financial sanctions and the international backlash against the dollar. Oxford University Press.

Naceur, S. B., Hosny, A. & Hadjian, G. (2019). How to de-dollarize financial systems in the

Caucasus and Central Asia?. Empirical Economics, 56(1), 1979–1999.

New York Times. (2018). U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Turkish Officials Over Detained American Pastor. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/01/world/europe/us-sanctions-turkey-pastor.html

Palley, T. (2022). Theorizing dollar hegemony, Part 1: the political economic foundations of exorbitant privilege. Post-Keynesian Economics Society, Working Paper Series, No. 2220.

Perks, M., Yudong, R., Jongsoon, S., & Tokuoka, K. (2021). Evolution of Bilateral Swap Lines. IMF Working Paper, WP/21/210.

Plubell, A. M., & Siyao, L. (2017). A Snapshot of Renminbi Internationalization Trends under One Belt One Road Initiative. MPEA Legal & Regulatory Bulletin, 9–11.

Quenan, C. & Edgardo, T. (2007). Changing the focus of the exchange rate regimes debate in emerging economies: causes and scope of de-dollarization in Latin America. Conference on “Ouverture et innovation sur les marchés financiers émergents,” Beijing, China.

Ramos, J. (2023). BRICS Bank Implementing 3-Year De-Dollarization Plan. https://watcher.guru/news/brics-bank-implementing-3-year-de-dollarization-plan

Rana, P. B. & Chan. E. (2022). Reforming the Global Reserve System. In W. Wu & M. W. Frazier (Eds.), From Centralised to Decentralising Global Economic Architecture: The Asian Perspective (pp. 113–130). Palgrave Macmillan.

Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (n.d.). Türkiye’s Multilateral Transportation Policy. https://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkey_s-multilateral-transportation-policy.en.mfa#:~:text=Trans%2DCaspian%20East%2DWest%2DMiddle%20Corridor%20Initiative%20shortly%20named,the%20efforts%20to%20revive%20the

Reuters. (2022). Turkey’s Erdogan targets joining Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, media reports say. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-erdogan-targets-joining-shanghai-cooperation-organisation-media-2022-09-17/

Reuters. (2023). Yuan overtakes dollar to become most-used currency in China’s cross-border transactions. https://www.reuters.com/markets/currencies/yuan-overtakes-dollar-become-most-used-currency-chinas-cross-border-transactions-2023-04-26

RMB Tracker Document Centre. (2022). Swift. https://www.swift.com/our-solutions/ compliance-and-shared-services/business-intelligence/renminbi/rmb-tracker/rmbtracker- document-centre

Russell, C. (2015). Who’ll Win? Visa and MasterCard Versus UnionPay—CKGSB. CKGSB Knowledge. https://english.ckgsb.edu.cn/knowledges/wholl-win-visaand- mastercard-versus-unionpay

Sharma, V. B. (2023). Debates around De-dollarisation and Yuan Internationalisation. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/04/30/debates-around-de-dollarisation-and-yuan-internationalisation

Sharp, A. (2023). U.S. Imposes Landmark Sanctions on Turkey. https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/14/us-turkey-sanctions-russia-ukraine-shipping-nato/

Siddiqui, K. (2023). De-dollarisation, Currency Wars and the End of US Dollar Hegemony. The

World Financial Review, August-September, 1–13.

Slawotsky, J. (2020). US Financial Hegemony: The Digital Yuan and Risks of Dollar De-Weaponization. Fordham International Law Journal, 44(1), 39–100.

Song, K., & Xia, L. (2020). Bilateral swap agreement and renminbi settlement in cross-border trade. Economic and Political Studies, 8(3), 355–373.

Soni, N. & Jain, P. (2023). Challenges to the Us Dollar Hegemony and Emergence of Yuan in

the Current Multipolar World. Korea Review of International Studies, 16(1), 53–73.

Soylu, R. (2022). Turkey’s love affair with currency swaps explained. Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-central-bank-swap-deals-love-explained

Statista. (2023). Gold reserves of largest gold holding countries worldwide as of 2nd quarter 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267998/countries-with-the-largest-gold-reserves/

Statista. (2022). Leading gold importing countries worldwide in 2022 based on value (in billion U.S. dollars). https://www.statista.com/statistics/920874/gold-import-value-by-leading-country/

Steinbock, D. (2023). The Coming BRICS Currency Diversification. https://www.chinausfocus.com/finance-economy/the-coming-brics-currency-diversification-24834

TASS. (2018). BRICS talks Turkey: Erdogan’s wish to join group cannot be fulfilled now, expert says. https://tass.com/world/1015343

teleSUR. (2023). BRICS Currency to Facilitate International Settlements: Glazyev. https://www.telesurenglish.net/news/BRICS-Currency-to-Facilitate-International-Settlements-Glazyev-20231024-0007.html

The State Council of the & People’s Republic of China. (2023). Digital Yuan in Circulation Hits 13.61 Bln Yuan in 2022. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202301/25/content_WS63d0ca26c6d0a757729e607d.html

Tran, H. (2022). Internationalization of the Renmibi via Bilateral Swap Lines. Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/internationalization- of-the-renmibi-via-bilateral-swap-lines

Vasudevan, R. (2021). Dollar Standard and Imperialism. In I. Ness & Z. Cope (Eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and anti-Imperialism (pp. 602–613). Springer.

Vidal, J. A., et. al. (2022). Policies for transactional de-dollarization: A laboratory study. Journal

of Economic Behavior & Organization, 200(1), 31–54.

Wilson, J. D. (2017). What Does China Want from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank? Perth USAsia Centre. https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/ id/eprint/37439

Xueying, W., Dongsheng, D. & Ruiling, L. (2022). The Evolving International Monetary System: Will Dollar Hegemony Outlive the Digital Revolution?. In P. B. Rana & J. Xianbai (Eds.), From Centralised to Decentralising Global Economic Architecture (pp. 131–160). Springer.

Yan, C. (2023). The Impact of Russia’s “De Dollarization” on the International Status of the US

Dollar. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 5(2), 17–21.

Yang, L. & Ziaojing, Z. (2017). Internal and External Imbalances and Currency Hegemony. In P. B. Rana & J. Xianbai (Eds.), Imbalance and Rebalance (pp. 119–149). Springer.

Yuan, T. (2018). The Dual-Center Global Financial System. Springer Singapore.

Zhang, F., Yu, M., Yu, J., & Jin, Y. (2017). The Effect of RMB Internationalization on Belt and Road Initiative: Evidence from Bilateral Swap Agreements. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 53(12), 2845–2857.

Zongyuan, Z. L. (2022). China Is Quietly Trying to Dethrone the Dollar. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/21/china-yuan-us-dollar-sco-currency

Zongyuan, Z. L. & Papa, M. (2022). Can BRICS De-dollarize the Global Financial System?. Cambridge University Press.