We are very pleased to publish this original article by Stefania Fusero, analysing the extraordinary successes of China’s targeted poverty alleviation program. The Italian version of the article will be published in two parts in La Città Futura.

In May 2020, PBS, a US public broadcaster, aired “China’s War on Poverty”, a documentary film co-produced with CGTN (Chinese State Television). A few days later, Daily Caller, a right-wing news website, accused the documentary of being “pro-Beijing”. After Fox News followed suit, PBS removed the film from its network.

According to Robert L. Kuhn, the producer of the film, the eradication of poverty in China ought to be understood by everybody, owing to the relevance it bears for the entire planet.

It is undoubtedly the story of a huge success of China’s, therefore it is no surprise that the western media and political establishment does not want it to be known and autonomously evaluated across our “free” world, whose citizens are kept carefully sheltered from any positive news about China.

The film can still be watched on CGTN YouTube channel at this link.

Here we will try to illustrate how the PRC managed to eradicate extreme poverty ten years ahead of the schedule set out in the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

In 2000, all UN member states committed to achieve eight development goals by the year 2015, the so-called Millennium Development Goals, the first of which was to halve the number of people living in poverty. Whereas China managed to achieve the goal by 2015, other countries did not. Thus in 2015 the commitments were reaffirmed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity announcing seventeen Sustainable Development Goals to be achieved by 2030, the first and foremost of which was “to end poverty”.

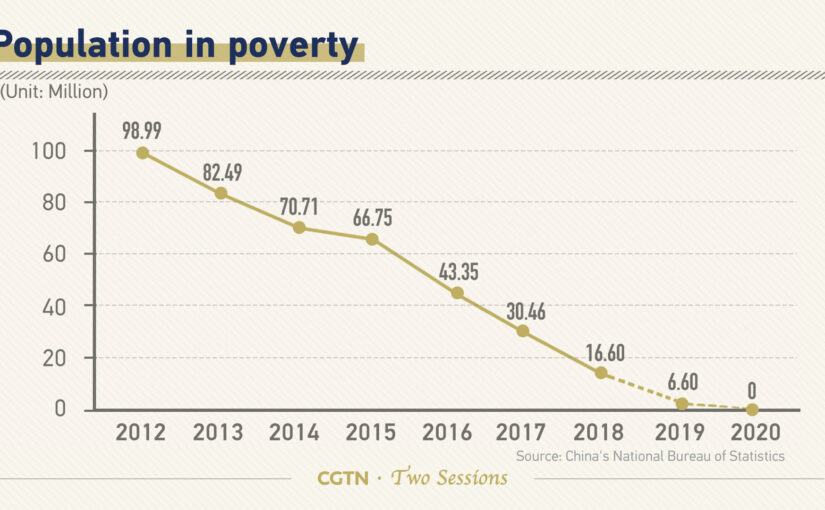

On February 25th, 2021, ten years ahead of the deadline set in Agenda 2030, the Chinese government declared that China had achieved the goal of eradicating extreme poverty. Being home to nearly one fifth of the world’s population, China alone had succeeded in reducing the world’s poverty-stricken population by over 70 percent. A milestone in the history not only of China, but of the whole of humanity.

How did they manage to complete such a painstaking colossal undertaking? – “act as an embroiderer approaching an intricate design”, president Xi urged the government of a rural village in Hunan in 2013.

First of all, we must bear in mind that the war on poverty began well before the millennium goals were set; this war began as soon as the People’s Republic of China was founded on October 1st 1949. In fact, even as early as during the fight between Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang and the Communists, the latter won the support of the people not only thanks to their determination in the liberation war against Japanese invaders – Japan had invaded Manchuria in 1931 – but also for the concrete actions they had been taking to emancipate the peasant masses.

China had been the world’s major economy at the beginning of the 19th century, but when the PRC was proclaimed after the “century of humiliation”, the bloody civil war against Chiang Kai-shek and the 14 year fight against Japanese imperialism, it was reduced to being one of the poorest countries in the world.

During the first years of the PRC, the Mao era, life expectancy increased from 35-40 in 1949 to 65 in 1976; if the population was 80% illiterate in 1949, in less than three decades illiteracy was reduced to 16.4% and 34.7% in urban and rural areas respectively; health care and child care improved; women were empowered and from the early fifties to the late seventies, the average industrial output grew annually by 11.3%.

In 1978 China started a series of reforms which broke its isolation from the rest of the world, and between 1978 and 2017, its economy grew in size by almost 35 times. The number of people living in extreme poverty decreased from 770 to 122 million in the period 1978-2011.

Unfortunately, though, that massive development brought about serious social and economic inequalities and caused heavy environmental devastation.

It was during a visit to Hunan in 2013 that President Xi first introduced the concept of the so-called “targeted poverty alleviation”, which began to be implemented in 2015.

Targeted Poverty Alleviation (tpa)

The strategy of “targeted poverty alleviation” (TPA), led by the government and carried out by effectively mobilising the whole society, can be summarised by the slogan: one income, two assurances (food and clothing) and three guarantees (basic medical services; housing with drinking water and electricity, and 9 years’ free compulsory education).

The campaign was guided by five basic questions: 1) who should be helped; 2) who should help; 3) how to help; 4) how to evaluate whether someone has emerged from poverty; 5) how to ensure that those people stay free from poverty.

Who should be helped

As well as income, housing, education and health were also taken into consideration when listing a “poverty-stricken household”.

The individuals and households in extreme poverty were identified by sending people to the villages (in the year 2014 alone as many as 800,000 party cadres were sent), who mobilised the local authorities, visited the families, organised public assemblies to discuss and integrate their data and finally deployed digital technologies to build a national database.

Subsequently, the data were checked, integrated and corrected through the deployment of over two million people.

Who should help

The CPC (Communist Party of China), with its over 95 million members, had obviously a central role: during the TPA about ten million cadres were sent to the impoverished villages, where they formed small teams living and working hand in hand with the targeted households, the local officials and the volunteers for one to three years on the average. One of their tasks was to ensure coordination among the various governmental and party levels – there are five levels of government in China: province, prefecture, county, township and village.

Yet we cannot stress highly enough that it was the entire Chinese society that mobilised at all levels to achieve the goals set by the government and the CPC, one core element of the TPA being the expectation that the rich, who concentrate historically in the eastern coastal areas, would help uplift the poor. If we rethink of Deng Xiaoping’s quote “let a few get rich first” in this respect, perhaps we can understand it better.

From 2015 to 2020, the whole country mobilised to accomplish that astonishing feat: besides the local administrative units – 343 eastern counties, in addition to sending their own officials and technicians, invested the equivalent of billions euros on the western regions – many local enterprises, both private and state-owned, invested and developed projects in a range of fields; the military contributed to building new hospitals and schools; many national social organisations raised charitable funds and offered voluntary services; the Ministry of Education dispatched expert and training teams in agriculture, health, planning and education from over 44 universities.

How to help

The TPA mainly took five measures for poverty eradication: 1) boosting the economy to provide more job opportunities; 2) relocating poor people from inhospitable areas; 3) compensating for ecological damage; 4) improving education in impoverished areas; 5) providing subsistence allowances for those unable to shake off poverty by themselves.

1) To boost the economy in all of the 832 counties identified as poor, China has created 12,000 local agriproduct brands and 719,000 rural cooperatives operated by farmers. Over one thousand innovative platforms have been set up and professionals have provided guidance on new technology, enabling poor households to form ties with new types of agribusiness entities and employ e-commerce to sell their products. Financial support like loans and microcredit has also been provided.

All this in turn has helped develop new models linked to tourism and the green economy.

2) More than 9.6 million people living in inhospitable areas suffering from harsh natural conditions and subject to frequent natural disasters were relocated to other areas on a voluntary basis.

The resettlement sites are provided with schools from kindergarten to middle school, hospitals, old age care facilities, as well as cultural centres and venues.

Their former homes have been turned into farmland or planted with trees, to improve the eco-environment in these areas.

3) The third measure taken to shake off poverty was compensating for economic losses associated with reducing ecological damage and getting eco-jobs. Laying equal emphasis on poverty alleviation and eco-conservation, China has strengthened ecological restoration and environmental protection in poor areas, increased government transfer payments to key eco-areas, and expanded the scope of those eligible for preferential policies.

Since 2013, a total of 4.97 million hectares of farmland in poor areas has been returned to forest and grassland. A total of 1.1 million poor people have become forest rangers, and 23,000 poverty alleviation forestation cooperatives/teams have been formed.

FAO ranked China as a global leader in reforestation, accounting for 25 percent of the total growth in leaf area between 1990 and 2020. The greening efforts have been taken up not only through government efforts, but also through private sector initiatives like Alipay.

4) Through education, poverty can be prevented from passing down from generation to generation. The government has continued to increase support for schools in poor areas to improve their conditions, standard of teaching, and financial resources.

All of China’s primary and secondary schools now have access to the Internet, and most have been equipped with multimedia classrooms; improved nutrition has also been offered in schools. Great efforts were made to ensure that the 200,000 school dropouts from poor families (as of 2013) had adequate support to return to school.

Seventeen million rural teachers have received training through the National Training Programme and altogether 190,000 rural teachers have been dispatched to schools in remote poor areas.

The government has offered training on standard Chinese language to 3.5 million rural teachers and young farmers and herdsmen in ethnic minority areas, in an effort to make poor people from these areas more competitive in the job market.

5) The fifth measure taken to implement TPA is social assistance.

The most vulnerable groups are provided with subsistence allowances. Services and facilities to support people living in extreme poverty have been upgraded, with a greater capacity to provide care in service centres. The per capita yearly rural subsistence allowances in rural areas have grown by 188.3% from 2012 to 2020.

Recognising that disease and poor health are key factors causing rural poverty, improving health care in the countryside has been key to the TPA programme with the number of hospitals increased and many health workers as well as medical students being dispatched to the impoverished areas.

In addition, telemedicine covers all poor counties and over one thousand leading hospitals have been paired up with county-level hospitals in poor areas.

How to evaluate whether someone has emerged from poverty

The assessment has been carried out yearly at the national level in three main ways: inter-provincial cross-assessment, third-party assessment and social monitoring.

A “grace period” is allowed for previously impoverished population, villages and counties, during which time poverty alleviation policies and government supervision are continued until their status is secure.

Clear provisions on the standards and procedures for deregistering from the list poor counties, villages, and individuals were made to avoid misconduct and also to prevent those who have emerged from poverty from keeping the label in order to continue accessing preferential treatment.

Despite the strict enforcement of criteria and procedures, the systematic evaluation processes revealed issues in the poverty alleviation programme, including mismanagement of funds, inaccuracy and falsification in registering data, and other disciplinary violations.

Among these problems is corruption. Since assuming office in 2013, Xi has made anti-corruption a high priority, and from 2012 to the first half of 2020, over 3.2 million officials were punished for corruption-related offences. The government found that one third of the 161,500 processed corruption cases – including 18 high-level officials – in 2020 were linked to poverty alleviation.

Unsurprisingly, the anti-corruption campaign has enjoyed widespread popularity, with the support for the government rising from 86 to 93% from 2003 to 3016, according to Harvard University.

How to ensure that those people stay free from poverty

China will continue to monitor any trends showing a return to poverty and implement any required support measures.

Households and locations will be considered to have been lifted out of poverty only when they have not fallen back for a fixed period, during which they can rely on the main support policies. Later on, the resources allocated to AMP will be directed towards rural revitalisation.

China will continue to support formerly impoverished areas in developing their specialty industries and help those who have emerged from poverty to have stable employment.

Systems and practices that have proven effective, such as resident first secretaries and working teams, eastern-western collaboration, paired-up assistance, and social assistance, will be continued and improved.

Efforts will be intensified to help those who have emerged from poverty build up self-belief and have access to education, so that they can create a better life through their own hard work.

Conclusion

Kuijiu is a remote village situated at 3,000 m above sea level in one of the poorest areas in Sichuan; most of its inhabitants are of Yi ethnicity. In 2019 Nadim Diab, from CGTN, shared for a period the tough life of a resident team of poverty relief officials.

One year later he returned there and shot the documentary “Working in China’s poorest village”.

We recommend viewing it, as it gives an insight into the tiny details constituting the “intricate design” woven by the men and women who shared, supported and helped improve the prohibitive living conditions of the villagers.

The “targeted poverty alleviation” campaign, far from being a gala dinner, was a war which took the lives of over 1,800 party members and officials.

After achieving the goal of eradicating extreme poverty, China has set the year 2035 as the target date to achieve common prosperity, which means providing the opportunity for a decent standard of living to all Chinese citizens, by ensuring equal access to education, health care, and other services.

Unfortunately, United Nations agencies report a great reversal in poverty elimination outside of China: in 2020, over 71 million people – mainly in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia – slipped back into poverty, and estimate that a total of 251 million people will be brought into extreme poverty by 2030, bringing the total number to over one billion.

For this report we have drawn liberally on “Serve the People: the Eradication of Extreme Poverty in China”, a study carried out by Tricontinental, an institute for social research who “stand, in the words of Franz Fanon, with the wretched of the earth to create a world of human beings.”

Therefore, we leave the conclusion to them: “The historic defeat of extreme poverty does not provide a model that can be directly implanted onto other countries, each of which has a specific history and distinct path to shape. Rather, China’s experience offers lessons and inspiration for the world, particularly for countries in the Global South. The task of uplifting the world’s poor is a key pillar of China’s proposal to build a ‘shared future for humanity’. This vision, advocated by President Xi, imagines a future that is based on multilateralism and shared prosperity in the face of Western hegemony.”

Sources

- Serve the People: the Eradication of Extreme Poverty in China

- Working in China’s Poorest Village, documentary

- World Bank on China’s Role in Efforts to Eradicate Poverty

- Millennium Development Goals

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- China’s State Council white paper “Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution.”

- FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment