In the following article, which was originally published in the Morning Star, Keith Lamb argues that Washington’s flattery of India and its encouragement of stronger ties with NATO, citing an alleged “Chinese threat”, is a trap into which New Delhi should not fall. The border dispute between India and China, he notes, is a legacy of British colonial aggression and India’s future lies in greater cooperation with China and the Global South generally. India’s support for the struggle of Mauritius to reclaim the Chagos Archipelago, a territory in the Indian Ocean which remains under illegal British colonial control and is home to a massive US military base, is cited by Keith as an example of how India grasps this imperative on some level. India’s interests, he argues would be well served by further consolidation of the BRICS grouping and greater promotion of regional energy integration and supply chains, not least the long-mooted Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) natural gas pipeline.

After a recommendation by the congressional committee on strategic competition with China, the US claims that India “is one of Washington’s closest allies.” As such, it is now courting India to join Nato to counter Chinese “aggression.”

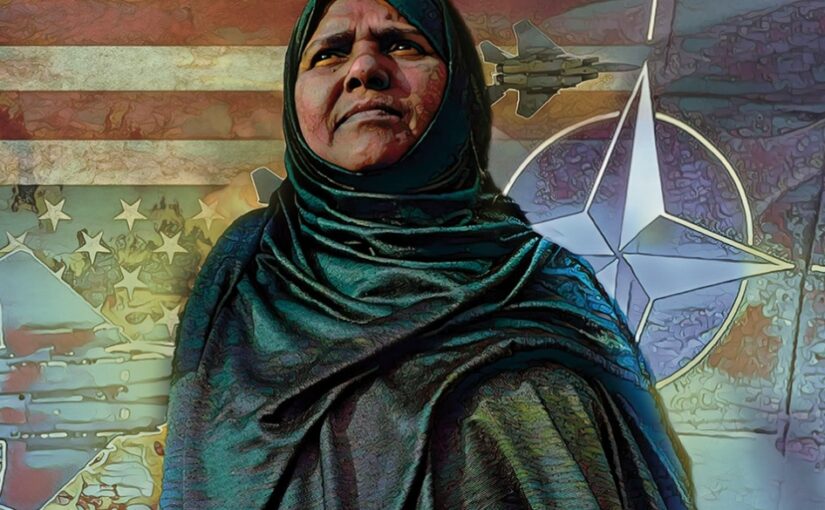

India must not fall to Washington’s flattery and the trumped-up China threat. Strategically and economically, India’s future lies with greater co-operation with China and the global South, not Nato, which opposes development.

In terms of Chinese “aggression,” the US hypes up the border dispute. This dispute is a remnant of British colonialism annexing Chinese territory.

China’s claims are rational, not expansionist — they exist due to British hegemonic attempts to swallow up both China and India.

Importantly, this dispute is managed unprecedentedly well. The line of actual control is patrolled by non-gun-carrying troops. This peaceful status quo would be ruined by US-led Nato machinations, which continue, under a different guise, the hegemonic project of the British empire.

Colonialism hasn’t finished — it is alive under US leadership which has a greater global military presence than under the British empire. It seeks, through its hard power, to divide the global South and bring it to heel — strategically this is what India’s invitation to Nato represents.

On one level, India understands this, which is why India backs Mauritius’s claim on the British-controlled Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean, which hosts a US military base capable of threatening the Indian subcontinent.

The US talks about developing India and using India as the new “world factory,” but due to hegemonic strategic concerns, a country the size of India will never be allowed to develop to a comparable standard to that of the US

Hegemonism doesn’t seek development — it seeks to exploit and it seeks unipolarity. Those who try to break out of the net of economic domination will be countered.

China is the perfect example of this. It co-operated with the US, but due to its huge size, even a modest standard of development is seen as a threat to unipolarity.

India, if successful, would encounter the same problem — though if it loses its independence to the cancer of Nato perhaps it will never develop beyond being a low-end factory.

Anyone who doubts the resolve of the US and its power to silently smother its Nato “allies” needs to revisit the Nord Stream pipeline bombing allegations.

Europe is now cut away from Eurasia and is more reliant than ever on transatlantic shipping for its trade and energy.

India, though artificially disconnected from Eurasia, due to politics and connectivity, unlike the Nato-led Europe, still has the independence to overcome these issues.

Political co-operation can be achieved through the Brics coalition, which is currently expanding based on the principle of win-win global South development, rather than Nato’s principle of preventing the rise of the global South.

India must choose what future it wants. Does it want to join an imperialist bloc that has committed atrocities against the global South or does it want to work towards peaceful neighbourly relations?

For the sake of India’s development, its border dispute must be resolved or sidelined — and this will never be allowed under Nato. India must recognise that if it is not connected to Eurasia then energy supplies for its industrial revolution and markets for its products will be limited.

US hegemonism favours a chaotic inland, which induces trade on its controlled shipping lanes. An unconnected India means, like Europe, expensively shipped-in energy supplies, disconnected markets and a reliance on the goodwill of the US not to disrupt shipping.

India’s solution is to construct Eurasian energy pipelines to fuel its economy. However, this goes against Nato interests. Indeed, Nato chaos in Afghanistan means that the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (Tapi) pipeline is still not built.

However, the good news is India has the desire to build Tapi. Besides Afghan security, this will require a solution with Pakistan, which has a serious, armed border dispute with India. If this can be achieved then obstacles with China can also be overcome and a Russia-China-India pipeline could be accomplished.

When it comes to markets, we are no longer in an age where finished goods from a “world factory” flow west. The whole premise of India “replacing China” as the new global factory is flawed.

India’s market for its products will increasingly come from China and the rest of the world. As such, India needs infrastructure connectivity with China’s growing giant market to remain competitive — it cannot rely on shipping through the Strait of Malacca.

The US doesn’t build infrastructure — its “Nato expertise” lies in destruction. In contrast, China builds.

Xizang’s (Tibet’s) development is evidence that China can develop even the most hostile of Himalayan environments and bring about rapid poverty alleviation — precisely what India needs.

Perhaps there is no quick fix to the border dispute, but Nepal provides the perfect conduit for Sino-Indian trade and infrastructure connectivity.

In a world where capital and technology are no longer Western monopolies, India would make a huge strategic blunder by believing otherwise. Just as markets for products are now dispersed, so is the source for capital investment and tech know-how.

Today, China’s market has upgraded significantly and its capital chases labour arbitrage and investment opportunities.

China’s technology can transform. Thus, considering the geographical proximity and the relative states of Indian and Chinese economies, there is much potential developmental synergy that would be dampened by joining Nato.

I am from Vancouver,Canada and i wanted to say that when India became Independent from England it kept the English laws that were used by England when England controlled India. I once asked a Co-Worker from India about that and he said that was true. That is keeping India down. These Laws need to be thrown out so that India can make progress.Hopefully that will happen soon.