We are pleased to republish this academic study by Eurispes – Istituto di Studi Politici Economici e Sociali, Centro Studi Eurasia-Mediterraneo and Istituto Diplomatico Internazionale, which provides a rigorous analysis of the situation in Xinjiang, in particular the emergence of the separatist terrorist movement and the Chinese government’s response.

The report provides a crucial corrective to the ‘Uyghur genocide’ narrative that has become pervasive in much of the West. We are republishing the English version, with permission. The original can be accessed in English and Italian from the Centro Studi Eurasia-Mediterraneo website.

Abstract

Over the past year, the Western media has given considerable attention to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). Newspapers, television programs and, above all, social media users have focused in particular on the alleged repression, by the Chinese government, of the local Uyghur community, a predominantly Islamic ethnic group with its own language (Uyghur, of Turkic origin) that has lived in the region for centuries, accounting for just over half of the total population. In Europe, the issue has caused consternation and indignation in public opinion, to the point of influencing politics, and convincing the foreign ministers of the member countries of the European Union to approve sanctions against some Chinese officials considered to be particularly implicated – according to the allegations – in the so-called “Uyghur genocide”.

However, the accounts and testimonies coming out of China, as well as from foreign journalists, diplomats, experts, students and professionals who have had and continue to have the chance to visit Xinjiang and its cities and counties, tell a very different story, which seriously undermines the West’s charges.

The detention and re-education camps, are, in fact, shown to be confinement and de-radicalisation centres for men and women affiliated with terrorist groups, such as the East Turkestan Liberation Organization (ETLO) and the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which for several years have been carrying out attacks not only in Xinjiang but elsewhere in China as well, and even abroad, against Chinese targets (diplomatic representations, tourist groups or companies) or targets of other nature, as evidenced by the presence, reported in recent years, of ethnic Uyghur fighters among the ranks of ISIS in the Syrian and Iraqi conflicts.

This report thus seeks to shed light on a topic – that of the social and political situation in Xinjiang – that is much broader and more complex than the simplistic accounts and allegations of the Western mainstream press, whose sensationalistic narrative risks generating serious diplomatic tensions, undermining consolidated bilateral or multilateral cooperation platforms and, last but not least, providing sectarian, violent and subversive groups with a very dangerous political and moral legitimacy.

- HISTORICAL, GEOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

Comprising 47 ethnic groups (13 of which are predominant) and numerous religious communities (Islamic, Buddhist, Taoist, Christian, etc.), Xinjiang is undoubtedly the most culturally and socially diverse region in China. Currently, the Uyghurs represent 51.14 per cent of the local population, with an increase compared to 2010 (when they were 45.84 per cent of the total)1. Yet their ethnogenesis – to use a term dear to the Russian scholar Lev N. Gumilyov2 – has only a marginal connection to what is today known as Xinjiang.

The Uyghur Khaganate, born in 744 AD from the fragmentation of the First Turkic (or Gokturk) Empire, held a much larger territory, encompassing Lake Baikal, the Orkhon Valley and the Altai Mountains. Its two capitals, Otuken and Ordu-Baliq, were located in the heart of present-day Mongolia, not far from the place where a few centuries later Genghis Khan would establish Karakorum, the capital of the gigantic Mongol Empire, before Kublai Khan decided to move the heart of the political and economic power of the Yuan Dynasty to Khanbaliq (or Dadu), the site of present-day Beijing.

The Chinese presence in the area, however, dates back to many centuries earlier, to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (Han Wudi), who in 138 BC sent the general and diplomat Zhang Qian3 to the Tarim River basin, the geographical heart of today’s Xinjiang, from which he then reached Lake Balkhash, located in today’s Kazakhstan, the Fergana Valley (Sogdiana) and Bactria. The conquests of the Han Dynasty thus opened the route of the Silk Road to the west, in the same places where Alexander the Great had marched two centuries earlier, hailing from Macedonia.

Today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region covers an area of about 1.66 million square kilometres, making it the largest administrative subdivision of the entire People’s Republic of China (PRC). The region’s territory, extremely composite and very biodiverse, is among the most inaccessible in the world. It is the home of the fearsome Taklamakan Desert4, around which numerous oasis cities such as Kashgar, Korla, Kucha, Aksu, Turfan, Hotan and others arose over the centuries, acting both as places of rest and refreshment as well as trade hubs. Xinjiang is still largely uninhabitable today.

The region has a total of 14 prefectures, 99 counties and 1,005 villages, but the anthropised areas, where about 25 million people reside, correspond to only 9.7 per cent of the region’s territory, while the remaining 90.3 per cent is comprised of mostly uninhabited hills, deserts and water catchment areas5. In addition to the desert, the striking mountain ranges of the Altai, Tien Shan, Pamir and Kunlun – shared respectively with Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan and with the Chinese provinces of Tibet and Qinghai – surround the most important cities, including the regional capital Urumqi (about 3.5 million inhabitants), largely preventing any further urbanisation.

The energy sector has historically been the driving industrialising force in Xinjiang. Following the discovery of the first oil and gas fields in the Karamay area, in 1955, a great process of modernisation began, which made it possible to identify other large oil and gas fields scattered throughout the Tarim basin, such as those of Tazhong, Kela and Yaha- Yingmaili. Refineries and petrochemical plants have thus driven the growth of the region, which subsequently experienced the rapid rise of other mining sectors, such as coal, in particular in the Turpan-Hami area, gold, especially in the Altai area, and steel6.

According to the data contained in the report Build a beautiful Xinjiang, realize the Chinese Dream, published by the State Council and presented in 2019 by the regional governor Shohrat Zakir, Xinjiang’s GPD has increased from 791 million yuan (€97.69 million) in 1952 to 1,220 billion yuan (€159.67 billion) in 2018, at an average annual rate of 8.3 per cent7. These numbers speak of more than just economic growth; they reflect a radical economic transformation of local society, which, alongside traditional activities linked to agriculture, fishing and livestock (themselves modernised on the wave of new technologies), developed a thriving industry, with interesting model cases of innovation, such as the Urumqi Economic and Technological Development Zone (UETD), inaugurated in the first half of the 1990s, and a promising service sector.

The industry in Xinjiang is deeply diversifying itself due to the consumption and environmental protection policies adopted by the Chinese government. Oil, gas, steel and coal logically continue to constitute a large part of local industrial activities, but old production methods have given way to cutting-edge and more sustainable plants, designed primarily to meet the demand of light industries and housing, stemming from the development of new residential districts, and of local infrastructures, such as highways, roads, railways, airports and the kind of “green” and “smart” urban furniture that has long distinguished Beijing and large coastal cities such as Shanghai, Shenzhen, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Hangzhou, Qingdao and others.

The infrastructural works carried out over the last forty years have made it possible to connect all the region’s main cities, counties and most of the villages to each other. In particular, the 552-km-long National Highway 315, inaugurated in 1995, connects the counties of Niya (transliterated from Mandarin Chinese as Minfeng) and Luntai, most of which runs through the dunes of the Taklamakan Desert. To prevent quicksand from spilling along the asphalt, vegetation was specifically planted on the sides of the carriageway, fed by complex irrigation systems. Another artery of fundamental importance is the National Highway 314, which connects Urumqi to the Khunjerab Pass, the gateway to the Pakistani region of Gilgit-Baltistan, by way of cities such as Korla and Luntai, where it intersects with the National Highway 315, Aksu and Kashgar, from which it continues south to merge onto the Karakoram Highway (N-35) reaching Hasan Abdal, in the northern reaches of the Pakistani province of Punjab.

In 2014, with the completion, after only five years, of the new 1,776-km-long high-speed railway, which runs parallel to the old Lanzhou-Xinjiang route, the region can be said to be fully connected to the national transport system. The trains, which travel at an operating speed between 200 and 250 km per hour, depart from the capital of Gansu, enter Qinghai for a short distance, re-enter Gansu, at the height of Minle County, and ultimately reach Xinjiang, where they stop at the stations of Hami, Shanshan, Turfan and Urumqi. The line, also used for freight transport to Europe, is part of an intercontinental corridor that starts from the metropolis of Lianyungang, in the coastal province of Jiangsu, and reaches Rotterdam, Europe’s largest seaport, passing through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany. In the January-July 2020 period, despite the pandemic, 899 intercontinental freight trains passed through Jiangsu – and therefore Xinjiang – of which 606 outbound and 293 inbound, a figure up 48.9 per cent compared to the same period in 20198. Another modern railway line nearly 490 kilometres long connects Hotan to Kashgar, passing through ten county towns9, all located in the southwestern territories of Xinjiang, and then joining another line that leads to Urumqi.

Air transport has also undergone a radical revolution, as evidenced by the Urumqi Diwopu International Airport, the real flagship of the infrastructural development commenced in Xinjiang, as in the rest of the country, with the introduction of the policies of reform and opening up (1978), as well as other minor airports, such as those of Kashgar, Karamay, Hami and others. In all, 22 civilian airports are currently active in Xinjiang. In 2018, over 23 million travellers10, both domestic and foreign, passed through the Urumqi airport hub, along what has been dubbed China’s “Air Silk Road”, centred on the Xi’an- Dunhuang-Turpan route. The two main passenger terminals (out of the four total) of the region’s capital offer connections with China’s main cities as well as with foreign airports in countries such as Russia, Singapore, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Thailand and others.

In a territory so hostile to human activities, this massive infrastructural development, which has considerably reduced the impact of natural obstacles on the times and modes of production and shipping, has played a decisive role in the growth of Xinjiang. In addition to the industrial logistics, even the tertiary sector has received a significant boost, particularly the hospitality sector, thanks to a growing boom in tourist inflows, for now mainly of national origin but with increasing numbers from abroad as well, primarily from Muslim countries of Turkic, Arab and Iranian tradition, where there is a strong interest in the numerous cultural and religious sites of Xinjiang, redeveloped by the local government with resources from Beijing.

- TERRORISM AND SEPARATISM

The ideological origins of Uyghur separatism are twofold: pan-Turkism on the one hand and Islamism on the other. Among the extremist groups present in Xinjiang, these two aspects substantially overlap. In the rest of the Turkic world, however, they are historically quite distinct. By way of example, in Azerbaijan, a strong pan-Turkic ethnic sentiment re-emerged in various strata of society following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but the predominant religion is Shia Islam, which is widespread in the Persophone world, rather than the Sunni Islam, which characterises the so-called political Islam.

In Turkey, the Nationalist Movement Party (Milliyetgi Hareket Partisi – MHP), the political arm of the infamous Grey Wolves movement (Bozkurtlar), was created in 1969 on the basis of the pan-Turkic-inspired ideas and theories of Colonel Alparslan Turkey, which called for the unity of all people of Turkic origin, on the basis of Turanism, and even went as far as imagining a utopian reunion of all those groups believed to have a common Ural-Altaic origin: Turks, Mongols, Finno-Ugrians, Koreans and Japanese. The ideological reference, linked to the nineteenthcentury theories of Armin Vambery11, was therefore to the pre-Islamic past of the Turkic peoples, symbolised by the wolf, a sacred animal in the Turko-Mongol tradition. In more recent years, however, the Turkish nationalists of the MHP have repositioned themselves on “syncretic” positions, which favour the Turkish-Islamic synthesis, to try to intercept the conservative electorate potentially disappointed by the ruling AKP party.

Less widespread but equally present, the pan-Turkic sentiment is also popular in the four former Turkic-speaking Soviet republics of Central Asia, namely Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan. Here, starting from the eighteenth century, in various phases and on several occasions, Tsarist expansionism first and then Soviet reannexation triggered and consolidated a historical process not only of conflict, as evidenced by the military conquests of 18391895 and the Basmachi revolt between 1916-193412, but also of interaction (and partial mingling) with the Eastern Slavic culture which, thanks to its multi-ethnicity, multi-confessionalism and secularism, contributed for a long time to weaken the most extremist forces present in Central Asia. These, however, reemerged between the 1990s and the 2000s, in particular in Uzbekistan, although on a religious and non-ethnic basis13.

- Past wars and revolts

Implicated, in spite of themselves, in the strong tensions that exploded in the neighbouring territories of the so-called “Russian Turkestan”, the Muslim communities of Xinjiang, less numerous and geographically separated from their “brethren” of the Central Asian steppes, were equally receptive to both pan-Turkic and Islamist influences already from the mid-nineteenth century.

The first significant Islamist uprisings that broke out in China, of which we have clear reports, began in 1862 with the insurrection of some militias of the Hui ethnic group, at the time also known in Russia by the name of Dungans, who took the reins of a front of Chinese Muslim dissident communities, including the Uyghurs.

Riots broke out not only in Xinjiang, where Yaqub Beg, an Uzbek adventurer originally from the Kokand Khanate, who fled the Tashkent front after the first Russian offensive in 1864, was active, but also in the provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia. In a few years, taking advantage of the climate of strong political and social instability, Yaqub Beg, who took refuge in Kashgar, conquered the most important centres of Xinjiang, giving life to a Turkic-Islamic kingdom called Yettishar (or Kashgaria), which, in addition to the capital Kashgar, also included Khotan, Yarkand, Aksu, Yengisar and Kucha, even managing to get the recognition of the Ottoman Empire in 1873.

China’s obvious military superiority, and Yaqub Beg’s misrule, who came to be seen by many Uyghurs as a foreign despot, paved the way for the Chinese reconquest of the region, which took place in 1877 with the expedition commanded by General Zuo Zongtang, sent to the North-West of the country by the Qing dynasty. In 1881, with the signing of the Treaty of St. Petersburg, which established the return to China of the eastern portion of the Ili Valley, occupied by Russia during the Islamist uprisings, Xinjiang returned entirely to China and three years later was transformed into a province.

The normalisation of the north-western region, however, didn’t last long. With the fall of the Qing dynasty and the rise to power of the Kuomintang, following the Xinhai Revolution of 1911-1912, Xinjiang, as the rest of the country, was plunged into instability for several years, at least until the Northern Expedition that reunified China under the command of Chiang Kai-shek, with the support of the Chinese Communist Party in the framework of the First United Front (1924-1927), then dissolved following the purges conducted by the nationalist general against both the Communists and the left wing of the Kuomintang.

The Kuomintang’s management of power in Xinjiang was controversial. Throughout its reign, the party appointed three rulers to the region: Yang Zengxin, Jin Shuren and Sheng Shicai. The first, who adopted a strongly repressive policy, was assassinated by Islamist rioters in 1928. The second, who replaced him, had to face internal rebellions and the growing Soviet influence on the region, also driven by the construction of the Turkestan-Siberia railway line. The annexation, in 1930, of the Kumul Khanate, a semi-autonomous feudal Turkic khanate within the Qing dynasty, located in north-eastern Xinjiang, triggered the revolt of the local Muslim communities. Thanks also to the insubordination of the Hui Chinese Muslim general Ma Zhongying, the Muslim revolts raged on until 1934. Meanwhile, in Khotan, the three brothers Muhammad Amin Bughra, Abdullah Bughra and Nur Ahmad Jan Bughra instigated revolts there as well and proclaimed the birth of a local emirate inspired by Jadidism14, a movement of modernist reform among

Muslim intellectuals in Central Asia, while in Kashgar the rebel leader Khoja Niyaz ascended to the top of the newly formed Turkic Islamic Republic of East Turkestan, an unrecognised state founded on sharia law that lasted only five months, from November 1933 to April 1934.

The Kumul rebellions ended that same months following a massive Soviet military intervention, called for by Sheng Shicai, who in the meantime had been appointed as the new governor of Xinjiang, a de jure Chinese province that was de facto fully part of the Soviet orbit. Indeed, in the summer of 1934, having neutralised Ma Zhongying’s last rebel outposts, also supported by Chiang Kai-shek himself with the aim of eliminating Sheng Shicai and pushing back Moscow’s influence on the region, Stalin imposed on the governor a political, economic and commercial agreement that practically made Xinjiang another Soviet republic, separated from the rest of China. In terms of contents and political orientation, this, more than the self-proclaimed republic of Khoja Niyaz, can be considered a continuation of the second experience of independence, that of the so-called Second East Turkestan Republic, born under the leadership of Elihan Tore in December 1944, following Sheng Shicai’s ouster a result of his constant political scheming15, thus plunging Xinjiang into a climate of strong political instability.

The revolt started from the north, that is, from the Ili River Valley, and was led by Ehmetjan Qasim, an Uyghur trained in the Soviet Union, who took advantage of the chaos to try to eliminate the fragile grip of the Kuomintang over the region. The inter-ethnic clashes between Han and Uyghurs (but also between Uyghurs, Hui and Tajiks) became increasingly intense between 1945 and 1947, overlapping with the Cold War that was slowly emerging from the ashes of World War II. On the one hand was the Soviet Union, which supported the three rebel districts of Ili – Yili, Tacheng and Ashan (today Altai) -with their capital at Yining (Ghulja). On the other hand were the United States which supported the Kuomintang against the backdrop of the last phase of the Chinese civil war, which saw the Kuomintang and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party vying for political power over the entire country.

The hostilities ended only in the late summer of 1949, when five leaders of the Three Districts – namely Ehmetjan Qasim, Abdulkerim Abbas, Ishaq Beg, Luo Zhi and Delilhan Sugurbayev – boarded a Soviet plane bound for Chita, which mysteriously crashed near Lake Baikal. Ten days later, the other three leaders of the Three Districts, including Saifuddin Azizi, headed to Beijing by train to communicate their readiness to integrate Xinjiang into the nascent People’s Republic of China. Many of the revolutionary leaders of the Three Districts are still remembered and celebrated in China for their contribution to the civil war against the Kuomintang.

- Before and after September 11th: from war to terrorism

Shortly after the end of the Cold War, two sets of factors breathed new life into Xinjiang’s violent separatist movements, after decades of relative stability following the region’s incorporation into the newly formed People’s Republic in the autumn of 1949:

- With the Belavezha Accords, and even more so with the subsequent Alma-Ata Protocols and the consequent dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the five Soviet republics of Central Asia gained a legitimate but fragile independence, exposing themselves to numerous risk factors such as political instability, economic crisis and institutional weakness. In Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, the solidity of the local leadership remained virtually unchanged, preserving, albeit in a semi-authoritarian and paternalistic climate, the capacity for governance. In Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, on the other hand, local authorities were confronted with crisis, civil war, violent inter-ethnic clashes and serious episodes of terrorism for several years.

- In 1996, the Taliban rose to power in Afghanistan, resulting in the country’s transformation into a militant Islamist emirate, based on a complex body of thought strongly rooted in Sunni fundamentalism16.

China avoided any direct or indirect involvement in the civil war that pitted the Taliban, supported by Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, against the Northern Alliance, a united military front that included Abdul Rashid Dostum (Uzbek), Ahmad Shah Massoud (Tajik), Haji Muhammad Mohaqiq (Hazara), Abdul Haq

(Pashtun) and Haji Abdul Qadeer (Pashtun), all of whom had fought each other in the previous decade but enjoyed broad international support at that stage (from Russia, the United States, India, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) in the common fight against the Taliban. However, after 9/11, the direct involvement of the United States on Afghan soil opened a phase of further instability, which continues to this day, almost twenty years after the intervention began.

These developments allowed fundamentalist groups operating in Central Asia and Afghanistan to rekindle and offer their support separatist activities in nearby Xinjiang as well, educating and training new Uyghur activists, attracted by easy money and dystopian fantasies, particularly in Afghanistan.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the myth of the so-called “East Turkestan” suddenly came back into fashion in some Koranic schools of Xinjiang, boosting the ranks of new or regenerated terrorist acronyms from the past.

The Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) is among the most violent and active formations in the region. ETIM, which sees itself as an heir to the East Turkestan Islamic Party (ETIP), created by Zeydin Yusup in 1988, was founded in 1997 by Hasan Mahsum, a native of Shule County, Kashgar, who was killed in 2003 during of an anti-terrorism operation conducted by the Pakistani special forces in the province of South Waziristan. After his first terrorist activities and his subsequent arrest in the early 1990s, Hasan Mahsum, also known as Abu-Muhammad al-Turkestani, came into contact with the Taliban and with Osama bin Laden himself, who in early 1999 offered him financial assistance. Thus, in 2000, ETIM received a sum equal to 300,000 dollars from the terrorist sheikh and the Taliban, who the following year fully covered the expenses incurred by the organisation17 to acquire armaments, equipment, documents and false passports in order to expatriate and participate in training or actual fighting in the field.

Following the September 11 attacks and the start of the US intervention in Afghanistan to end the Taliban rule, ETIM was classified as a terrorist organisation not only by China but also by the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, Pakistan, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

In November 2020, however, the US State Department announced that it had removed the group from its blacklist because “for more than a decade, there has been no credible evidence that ETIM continues to exist”, sparking China’s backlash against what Beijing considers an unjustifiable double standard in the face of international terrorism18.

As a matter of fact, ETIM has continued to operate for years under the command of the various successors of Hasan Mahsum, starting with Abdul Haq, also known as Maimaitiming Maimaiti, indicated by Washington itself as a member of al-Qaeda’s Shura Council and accused by US authorities of actively recruiting fighters with the aim of conducting terrorist attacks and acts of sabotage in China, before and during the 2008 Beijing Olympics19. More recently, video testimonies and several intelligence sources have confirmed the presence, at least since 2015, of a large number of Uyghur jihadists in Syria. This flow of fighters coming mainly from the Uyghur diaspora in Turkey has been monitored in recent years by the Jamestown Foundation in Washington, which has indicated the presence of hundreds of militiamen from the Central Asian republics and Xinjiang among the ranks not only of the ISIS but also of other fundamentalist formations such as Jabhat al-Nusra20.

The analyst Jacob Zenn, in particular, has noted that that “in [Xinjiang], which is home to more than 10 million Uighurs, many attacks are not reported in the media. But [even] if you look at only reported attacks, well over several hundred people have been killed in attacks with mobs using daggers and even individuals using car and suitcase bombings in public plazas and train stations”. He also added that: “While originally the agitation in Xinjiang was ethno-nationalist, I think it would be fair to say that, like the Chechen case, now the ideology is mostly moving toward the Salafist jihadist trend”21.

The East Turkestan Liberation Organization (ETLO), founded in 1990 or 1996 by the terrorist Mehmet Emin Hazret, is another separatist formation that has been planning and carrying out attacks on sensitive targets in the Xinjiang region for years. The classification of the group’s extremist activities, however, has been the source of much controversy at the international level. The US government has always refused to include the ETLO in the list of international terrorist organisations, despite its numerous connections with al- Qaeda22, reported not only by China but also by Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, that are countries where the ETLO is responsible for killings, attempted murders, poisonings and robberies for funding purposes. One of the ETLO’s most emblematic attacks is without a doubt the execution of Nighmet Bosakov, president of the Uyghur Youth Alliance of Kyrgyzstan, shot dead in front of his home in Bishkek in March 2000.

Beijing includes among the terrorist groups also the World Uyghur Congress (WUC). The WUC is a non-governmental organisation founded in Munich in 2004 by a group of dissidents who escaped from China. It is centred around the figure of Erkin Alptekin, a Uyghur activist and son Isa Yusuf Alptekin, an old Uyghur official of the Chinese Kuomintang during the Republic of China (1912-1949) but above all a strong supporter of panTurkic ethno-nationalism and a rabid anti-communist, which led him to fight both against Soviet influences in Xinjiang in the 1930s and against the People’s Republic, from which he fled in 1949 to live in Turkey, where he died in 1995.

However, the real driving force behind the separatist cause abroad is Rebiya Kadeer, who was born in the city of Altai, in the Xinjiang prefecture of the same name. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s she was a successful entrepreneur (especially in the fields of commerce and real estate) and worked her way up to high-level positions within the Chinese Communist Party, even becoming a delegate to both the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s two top legislative and consultative bodies. Rebiya Kadeer was arrested in 1999 on charges of having sent conspicuous amounts of money to Uyghur separatist groups abroad through her second husband Sidik Haji Rouzi. She was released in 2005 for health reasons and a few days later, under the protection of Condoleezza Rice, the US Secretary of State of the George W. Bush Administration, she flew to the United States, where she was appointed president of the WUC, a position she held until to 2017, when he gave way to another key figure of Uyghur separatism abroad, Dolkun Isa, who is still in office.

In the United States, however, the Uyghur American Association (UAA) was already active since 1998, when it was founded by the activist Rushan Abbas, who moved to Washington in 1989 to pursue her studies. Having obtained US citizenship, Abbas initially founded, in 1993, the Uyghur Overseas Student and Scholars Association and then, five years later, she became the first Uyghur-language correspondent for Radio Free Asia, a Washington-based private, non-profit corporation created in 1994 on the model of Radio Free Europe and financed through the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), which is defined as an “independent federal government agency”23. The peculiarity of Radio Free Asia is that its Board of Directors is chaired by the same CEO and Director of USAGM: Taiwanese-American journalist and entrepreneur Kelu Chao24. Basically, the head of the (government) financing body coincides with the head of the (private) financed company’s board of governors.

Since 2002, Rushan Abbas has frequently collaborated, as an interpreter, with the State Department and the United States Congress in the context of Operation Enduring Freedom, the official name for the “war on terror” launched by the Pentagon in Afghanistan following the terrorist attacks of September 11th. He also participated in several congressional hearings on the human rights situation, history and culture of the Uyghur population, as well as making his knowledge available to various US federal and military agencies25.

In general terms, we are speaking of a galaxy of mass media and non-governmental organisations that actively support, through a legal structure and an institutional profile, the jihadist organisations present in Xinjiang, exert pressure on Congress and the US government and seek to influence public opinion in Western countries by resorting to the dissemination of news that, given the well-documented links between politics and media in the US, cannot always be considered reliable.

- BEIJING’S RESPONSE

The Chinese government, since the 1990s, has been faced with the problem of terrorist attacks perpetrated not only in Xinjiang, but also in other areas of the country, such as in Kunming, Yunnan, and even Beijing itself, or abroad, particularly in Kyrgyzstan but also in Turkey and Pakistan, against local markets, police offices, tourists, places of worship (including mosques or Islamic centres led by imams in disagreement with the separatists)26, entrepreneurs, ordinary citizens, embassies, consulates and businesses.

The response, usually limited to police interventions aimed at securing specific contexts, such as villages or urban neighbourhoods transformed into bases by terrorist groups, also involved special forces and military police, especially in the case of particularly delicate and complex operations such as those in extra-urban areas characterised by an orography that makes it difficult to patrol the territory.

The largest operation undertaken so far has undoubtedly been the one ordered by the central and local governments in July 2009, when for about a week violent riots shook the streets of Urumqi, as hundreds of extremists and terrorists targeted Han people but also Uyghurs themselves and other minorities who didn’t share the protestors’ ideas or methods. The events resulted in a very serious toll: 140 dead and 828 injured27. The capital of Xinjiang was placed in quasi-lockdown for several weeks, with Chinese military police patrolling the streets and hundreds of arrests made among those affiliated with terrorist organisations. A Chinese official, quoted by the Xinhua News Agency, explicitly blamed the riots on the World Uyghur Congress (WUC): “This was a crime of violence that was pre-meditated and organised”28. On the other hand, humanitarian organisations such as the US-based Human Rights Watch, which have always sided with the Uyghur diaspora, condemned the Chinese government’s response, demanding international inquiries to shed light on the arrests conducted in Urumqi, deemed – on the basis of uncertain and unverifiable evidence – indiscriminate or excessive in report released in October of that same year29.

- Characteristics of the terrorist phenomenon

The efforts of non-Western countries in the fight against domestic and international terrorism are often almost unknown in Europe. Like the concept of “international community”, even that of “anti-terrorism” seems to take on a different meaning depending on the place of origin of the extremist groups or the location of the attacks. This blatant double standard became self-evident during the so-called “Arab springs”, starting with the war in Libya. Following the fall of Muammar Gaddafi, caused by the military intervention of the NATO-led coalition in 2011, dozens of jihadist groups, in particular those close to the self-proclaimed Islamic State (IS), took advantage of the chaos and instability in the country to transform the former Italian colony in a massive recruitment and training base for fundamentalist fighters who were then sent or repatriated to Syria, Iraq and probably even to Europe to carry out the bloody wave of attacks of the 2015-2016 period30.

The Libyan example demonstrates, perhaps better than any other case, the typical “ripple effect” of terrorism, which makes it impossible to trace a clear border between the phenomenon’s domestic and international dimensions, especially when it comes to Islamist extremism. Contacts or links often arise between the various local organisations that favour the affiliation of local or national groups to transnational networks, which may be structured on a hierarchical-vertical basis or on a decentralised-horizontal basis, depending on the organisation’s ideology (fixed pattern) or on contingent factors (variable pattern).

An example of the former is represented by the Islamic State (IS), which on 29 June 2014 publicly proclaimed the birth of a self-proclaimed territorial state with the stated aim of expanding into the entire Muslim world – a practice virtually unknown in the history of international terrorism but which harked back to a very old tradition, that of the Caliphate (or something along those lines). The group’s first leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, died in 2019 and was replaced by Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al- Qurashi, the current Caliph of the Islamic State, who is flanked by a council of close collaborators, probably employed in the role of “administrators” or “generals”.

An example of the latter form of organisation, on the other hand, is represented by al-Qaeda (from the Arabic al- Qa^idah, “the base”). Despite the strong support it received by the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (that is, the Taliban) in the 1996-2001 period and the likely location of the leadership somewhere along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, Osama bin Laden’s creature has always remained essentially stateless and transnational. Moreover, following the death of its founder and his replacement by the Egyptian Ayman al- Zawahiri, al-Qaeda underwent a deep reorganisation, passing “from a pyramidal hierarchy to a more decentralised and horizontal one”, probably operating “according to the formula of the franchise”, whereby individual cells were allowed to conduct operations independently as long as they maintained “a certain ideological standard”, giving rise to the concept of leaderless jihad, that is, a jihad carried out by an individual or a small cell with minimal or even non-existent training on the part of the terrorist network31. It is the jihadist interpretation itself of the Koranic law, which is considered universally valid, indifferent to borders and latitudes, which should require governments around the world to maintain an identical and coherent point of view towards all terrorist phenomena, promoting the knowledge, cooperation and sharing of data and information globally, without dangerous ambiguities or value asymmetries. For many years now, China’s approach in the fight against terrorism has been based on the concept of the “three evils” – extremism, separatism and terrorism. At first glance, Beijing’s choice of placing on the same level what appear to be three distinct categories may seem like an attempt on the part of the Chinese authorities to blur the distinction between terrorism and legitimate political dissidence, as several Western observers have indeed hypothesised. In fact, these phenomena truly are intertwined, and not only in Xinjiang.

Their harking back to old state formations and previous (or even imaginary) forms of civilisation leads fundamentalist groups to pursue the goal of destabilising entire territories to redesign their geography, to the detriment of peace, socio-economic development and civil rights. Suffice to think of the awful treatment that women, minors and religious minorities were subjected to in the so-called Islamic State (al-Dawlah al- Islam沙ah) that was proclaimed between eastern Syria and north-western Iraq. Or of the Khorasan Group, presumably linked to al-Qaeda and which the former US National Intelligence Director James Clapper admitted that “in terms of threat to the homeland, […] may pose as much of a danger as the Islamic State”32. The group takes its name from the Greater Khorasan, an administrative region established by the Sasanian dynasty in the 6th century AD and inherited by the subsequent

Arab and Turko-Persian dominations, which included the present-day territories of north-eastern Iran, a large part of Afghanistan, the whole of Tajikistan and the southwestern regions of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, including also the Kyrgyz portion of the Fergana Valley.

A similar historical revisionism also characterises the terrorist groups active in Xinjiang, which use the definition “East Turkestan” to designate the region, which they claim to be the eastern portion of the vast historical-geographical area of Turkestan or the “Land of the Turks”, where “Turks” refers to the Ural-Altaic populations settled between the Caspian Sea and the Orkhon Valley. Clearly, this interpretation doesn’t take into account fundamental historical and political aspects, namely the previous Han and Tang dominations, the strong Chinese cultural influences during the rule of the Western Liao dynasty, also known as Kara Khitaj, the subsequent Qing dominations and, more in general, the traditionally multi-ethnic and multi-confessional character of Xinjiang, which was already one of the Silk Road’s thoroughfares more than a millennia before the conversion to Islam of Abdulkarim Satuk Bughra Khan (934 AD), the Kara- Khanid ruler of Kashgar.

- The SCO and China’s multilateral approach

For China, combating terrorism means first and foremost defending its borders and security. However, the aforementioned dynamism of the terrorist groups, on the one hand, and the growing international role of China, on the other, do not allow unilateral or isolated solutions but require shared analyses and strategies taken on a multilateral basis at several levels, starting with the regional one. Awareness of this led to the creation of Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), an intergovernmental body officially founded on 15-16 June 2001 by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan on the ashes of the old Shanghai Group, created five years earlier without Uzbekistan. In these twenty years, the Organization has grown significantly, increasing its areas of competence, not only in terms of security and cooperation, but above all by extending its scope following the accession of: India and Pakistan as countries members33; Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia as observer countries; and Azerbaijan, Armenia34, Cambodia, Nepal, Turkey and Sri Lanka as dialogue partners.

The first document approved by the SCO at the time of its foundation, even before the Charter of the organisation, signed in 2002 in St. Petersburg, was the Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism, signed on Shanghai on 15 June 2001 (with entry into force in 2003) and published in Chinese and Russian.

A more precise definition of the meaning of the three terms is provided in Article 135. By “terrorism”, the signatory parties mean any act, pursued under the national laws of the member countries, intended to:

- cause death or serious bodily injury to a civilian, or any other person not taking an active part in the hostilities in a situation of armed conflict;

- cause major damage to any material facility;

- organize, plan, aid and abet such act;

- intimidate a population;

- violate public security;

- compel public authorities or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act.

By “separatism”, the SCO means any act intended to violate territorial integrity of a State including by annexation of any part of its territory or to disintegrate a state, committed in a violent manner, as well as planning and preparing, and abetting such act. Finally, “extremism” is defined as “an act aimed at seizing or keeping power through the use of violence or changing violently the constitutional regime of a state, as well as a violent encroachment upon public security, including organization, for the above purposes, of illegal armed formations and participation in them”.

Article 2 establishes that the parties, in accordance with the Convention, other international obligations and their national legislations, shall cooperate in the area of prevention, identification and suppression of acts referred to in Article 1, and requires member countries to consider these offenses extraditable. The latter point, a fundamental aspect of cooperation among counter-terrorism authorities, meets the needs of individual states to prevent the flight of terrorist suspects to other member countries. Considering the foreign contacts of many Uyghur militiamen, which allowed them to move easily throughout Central Asia, in particular in the Fergana Valley36, in the Tajik Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region and in the rugged mountainous areas of Wakhan37, this decision has severely restricted their operating range.

Article 6 indicates the content of the cooperation between the parties, providing for: exchange of information; execution of requests concerning operational search actions; development and implementation of agreed measures to prevent, identify and suppress the acts referred to in Article 1, as well as mutual information on the results of their implementation; implementation of measures to prevent, identify and suppress, in the respective territories, the acts referred to in Article 1 that are aimed against other parties; implementation of measures to prevent, identify and suppress the financing, supplies of weapons and ammunition or any other form of assistance to any person and/or organisation for the purpose of committing the acts referred to in Article 1; exchange of regulatory acts and information concerning the practical implementation thereof; exchange of experience in the field of prevention, identification or suppression of the acts referred to in Article 1; various forms of training, retraining or upgrading of their experts; conclusion, upon mutual consent of the parties, of agreements on other forms of cooperation, including, as appropriate, practical assistance in suppressing the acts referred to in Article 1 and mitigating the consequences thereof38.

Article 7 goes into greater detail, explaining the kind of information that the competent authorities of the member states are required to pass on to the other members. This includes: planned and committed acts referred to in Article 1, as well as identified and suppressed attempts to commit them; preparations to commit acts aimed against heads of state or other statesmen, personnel of diplomatic missions, consular services and international organisations, as well as other persons under international protection and participants in governmental visits, international and governmental political, sports and other events; the names of organisations, groups and individuals preparing and/or committing acts referred to in Article 1 or otherwise participating in those acts, including their purposes, objectives, ties and other information; illicit manufacturing, procurement, storage, transfer, movement, sales or use of strong toxic, and poisonous substances, explosives, radioactive materials, weapons, explosive devices, firearms, ammunition, nuclear, chemical, biological or other types of weapons of mass destruction, as well as materials and equipment which can be used for their production, for the purpose of committing acts referred to in Article 1; identified or suspected sources of financing of acts indicated in Article 1, as well as forms, methods and means of committing such acts.

Article 10 referred to the future ratification of a separate agreement and the adoption of the necessary documents to establish and provide for functioning of a Regional AntiTerrorist Structure (RATS) headquartered in Bishkek, which is currently directed by 55-year-old Tajik Jumakhon Giyosov, who has been involved in his country’s national security sector since 1995.

- Evolution of the Chinese approach

Thus far, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has staunchly denied the charges levelled against it by its international critics of wanting to “hanify” the country by suppressing or absorbing the cultural, artistic and religious contribution of the non-Han population, equal to about 8 per cent of the total population. The CCP points claims to protect the country’s 55 ethnic minorities present in its vast territory.

Article 4 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China stipulates that all ethnic groups are equal: “The state protects the lawful rights and interests of the ethnic minorities and upholds and develops a relationship of equality, unity and mutual assistance among all of China’s ethnic groups. Discrimination against and oppression of any nationality are prohibited; any acts that undermine the unity of the nationalities or instigate their secession are prohibited”. Concerning the principle of local self-government, the constitution calls for “[r]egional autonomy [to be] practiced in areas where people of minority nationalities live in compact communities; in these areas organs of self-government are established for the exercise of the right of autonomy”, while at the same time emphasising that “[a]ll the national autonomous areas are inalienable parts of the People’s Republic of China”. All minorities are guaranteed “the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages, and to preserve or reform their own ways and customs”39.

The experience accumulated by the national counterterrorism forces both through the work carried out at home and within the intergovernmental structures of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization has allowed to raise the level of preparedness and effectiveness in the prevention of attacks, despite the difficult global context, with an alarming proliferation of new fundamentalist formations in the international Islamist galaxy in the aftermath of the outbreak, beginning in 2011, of new conflicts in the Arab world, first in Libya and shortly after in Syria. The renewed and more sophisticated terrorist threats led China to pass a new more surgical anti-terrorism law, approved on 27 December 2015, on the occasion of the 18th session of the Standing Committee of the 12th National People’s Congress, and entered into force on 1 January 2016.

To understand its meaning and scope, it is necessary to go back to 15 April 2014, when president Xi Jinping, during a meeting of the Central National Security Commission (CNCS), introduced for the first time the concept of “holistic approach to national security”. According to the Chinese head of state: “Internally and externally, the factors at play are more complex than ever before. Therefore, we must maintain a holistic view of national security, take the people’s security as our ultimate goal, achieve political security as our fundamental task, regard economic security as our foundation, with military, cultural and public security as means of guarantee, and promote international security so as to establish a national security system with Chinese characteristics”. In particular, Xi urged the government to “pay close attention to both traditional and non-traditional security, and build a national security system that integrates such elements as political, homeland, military, economic, cultural, social, science and technology, information, ecological, resource and nuclear security”40.

The new holistic or comprehensive approach to the scourge of terrorism therefore intends to harmonise various elements in relation to two areas of intervention:

- the range of anti-terrorism action, through the coordination of the internal and external dimensions;

- the content of the anti-terrorism response, through the integration between the security dimension as such and the socio-economic dimension.

This last aspect emerges quite clearly from the text of the 2015 Anti-Terrorism Law, which introduces a global strategy capable of addressing both the manifestations as well as the root causes of the terrorist phenomenon, specifying the government’s opposition to the use of any form of “distorted religious doctrines” or other ideologies that incite hatred or discrimination and/or promote violence and other forms of extremism, with the aim of eradicating the ideological basis of terrorism from society41. This should be understood as an attempt on behalf of the Chinese legislator to go beyond the simple prevention of the criminal act as such, in what could be defined a form of preventive prevention or pre- prevention42.

Clearly, the approach is very different from that adopted in Western countries, whose interest in the ideological component of terrorism is limited to the authorities’ investigative work, without any claim to have a moral and social impact on groups and individuals adhering to destructive ideologies. On the contrary, China exerts an ethical and cultural influence on society aimed at achieving full harmony between ethnic groups, social groups and intermediate bodies by the second 100-year milestone, set for 2049, when the People’s Republic of China, in its hundredth year of life, will have become a “a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful by the middle of the century”43, according to the roadmap drawn up at the 19th CCP Congress in October 2017. This is a substantial difference that, however, it is perfectly in line with the Confucian mentality that underpins state doctrine in many East Asian countries.

It should also be taken into account that in Western Europe and North America Islam is an alien religion, at most professed by very few native converts and by second or third generation residents, or the children or grandchildren of immigrants from Muslim majority countries. In China, on the other hand, as in Russia, India or Southeast Asia, Islam has a much older and more complex history, having penetrated in the region many centuries ago through cultural and commercial exchanges, establishing itself over time as a fully indigenous religious tradition, albeit a minority one, as evidenced by the case of the Hui, a Muslim community perfectly integrated in Chinese history and culture; indeed, Zheng He (1371-1434), the best known admiral in Chinese naval history, famous for the seven voyages that brought the mighty boats of the Ming dynasty to the shores of the Red Sea and a source of inspiration for the 21st century Maritime Silk Road project as part of the Belt and Road (BRI) initiative, was himself of Hui origin.

This means that Beijing has to tread carefully, striking a delicate balance between the need to avoid the violent and sectarian ideological distortions of Islam from spreading to the millions of Muslims present throughout the country, inside and outside Xinjiang, while at the same time ensuring that the anti-terrorism response doesn’t escalate into a violent and arbitrary reaction against the Uyghurs and other Muslim communities. Therefore, the government has a duty to ensure that the pro-active attitude of the Chinese security apparatus, which integrates repression and prevention of terrorist crimes44, remains within the boundaries of the law, of the respect and the protection of human rights as well as the protection of the legal rights and interests of citizens and groups45.

- CHINA-BASHING AND GEOPOLITICS

The Xinjiang issue has made a comeback over the past year, in conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic. Though the two issues are entirely unrelated, they have both been widely exploited, along with the approval of the new Hong Kong national security law, by several Western political leaders to point the finger at Beijing.

The media campaign on the origins of the virus and the conspiracy theories on the supposed “Wuhan lab leak”, although repeatedly rejected by the international scientific community46, have caused alarming ripple effects, including an upsurge in racist attitude towards East Asians in general, with several episodes of violence and xenophobia directed against Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, Thais and other communities of emigrants, students or even simple tourists.

In the United States alone, the Stop AAPI Hate organisation, led by Manjusha Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council (A3PCON), Cynthia Choi, co-executive director of Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA), and Russell Jeung, professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University, recorded 2,808 cases of racism and discrimination against American citizens of Asian descent between 19 March and 31 December 2020: 8.7 per cent of these cases involved physical assaults, and 70.9 per cent verbal harassment47. Episodes of xenophobia included cases of discrimination in the workplace and refusal of business, institutional, transport or car-sharing services.

The attacks, in general, mainly concerned the most vulnerable groups, such as young people under the age of 20 (13.6 per cent), people over 60 (7.3 per cent) and women, who were affected 2.5 times more than men48. Some of the most shocking cases include the murder of an 84-year-old Thai immigrant in San Francisco, who was violently knocked to the ground during his morning walk, the attack on a 91-year-old Asian- American in Oakland, an 89-year-old Chinese woman assaulted and set on fire by two people in Brooklyn, two Asian American women stabbed at a bus stop in San Francisco, and an Asian American woman hit in the head with a hammer by an unidentified assailant49.

The Chinese are obviously the most targeted ethnic community, making up 40.7 per cent of the cases, but the episodes of racism have also involved Koreans (15.1 per cent), Vietnamese (8.2 per cent) and Filipinos (7.2 per cent), while the states that have registered the most cases are California (43.8 per cent), New York (13 per cent), Washington (4.1 per cent) and Illinois (2.8 per cent)50. According to data from the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, discrimination against Asians in Orange County, one of California’s richest counties, by 1,200 percent, and by 115 percent in Los Angeles County51. Clearly, in the metropolises of these areas of the country, Asian natives are more present than in the Southern states, that are usually described as die-hard conservative and biased against non-white people, but these episodes seriously call into question these states’ reputation as open-minded and progressive places. AntiAsian attacks by African Americans and Hispanics are also not uncommon, demonstrating that the racial situation in the United States is much more complex than what one might infer based on the simplifications made by the mass media.

The accusations made over the past year by the United States and its main allies on the alleged Uyghur genocide taking place in Xinjiang and the supposed interment of one and a half million people in concentration camps52, are mainly based on the claims of a certain Adrian Zenz, an independent German anthropologist who has been speculating on the matter for years without ever having set foot in Xinjiang. Other testimonies reported in recent months have also called into question the statements made by two Uyghur women, Tursunay Ziawudun and Sayragul Sautbay, who claim to have been detained in the alleged interment and forced labour camps. Ziawudun, welcomed in the United States by the Uyghur Human Rights Project, has changed her version several times, first claiming that she had never been raped and never witnessed sexual violence53, and subsequently claiming to have been tortured and raped by a group of men54. Sautbay, who emigrated to Sweden, where she joined the Swedish Uyghur Association, a local subsidiary of the WUC (see chapter 1), initially stated that she has not personally witnessed any violence in the centres in question55; a year later, however, she was claiming to have witnessed “all kinds of tortures” in the detention centres56.

The aforementioned data from the official censuses carried out in Xinjiang refutes the proposition that such a large number of people of Uyghur ethnicity, or in any case of Muslim faith, could find themselves locked up in “detention camps”.

Furthermore, between 2018 and 2020, over 1,200 delegates from more than 100 countries – including UN officials, foreign diplomats, UN permanent representatives, journalists and religious authorities – were able to visit Xinjiang57 and didn’t find any evidence of an alleged plan to repress or suppress the local population on an ethnic or sectarian basis. Many scholars and witnesses have appreciated the reinstatement policies adopted by the Chinese government to promote the de-radicalisation and address the problem at its root. Some Muslim-majority countries, such as Kazakhstan and Indonesia, have imitated such policies.

We reproduce below some photographs of the Xinjiang “education and professional training centres”, which were established in 2015 with the aim of reinstating in society radicalised subjects who have been involved in illegal Islamist networks (a mission that has been largely fulfilled, to the point that several centres have been earmarked for closure). These photographs were taken on the ground by our researchers. To understand the nature of these centres, the last governmental white paper about Xinjiang can be useful too58.

When a group of 22 countries sent a joint letter to the 41st session of the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), on 8 July 2019, condemning the alleged mass incarceration of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, 37 countries, led by China, decided to respond with their own letter, presenting a diametrically opposite version of the facts. In the document, published just four days after the first letter, this second group of countries express their “firm opposition to relevant countries’ practice of politicizing human rights issues, by naming and shaming, and publicly exerting pressures on other countries”, praised “China’s remarkable achievements” in “protecting and promoting human rights through development”, called on the 22 signatory countries of the first letter “to refrain from employing unfounded charges against China” and urged the UNHRC to approach the Xinjiang situation “in an objective and impartial manner […] with true and genuinely credible information”59.

A few weeks later, despite Qatar’s withdrawal, the Beijing-led group presented an updated version of its letter, gaining the support of 13 other countries and of the Palestinian National Authority (non-member observer state).

The singular aspect is that the 22 signatory countries of the first letter, which doesn’t include Italy, are all Western, with the sole exception of Japan, while as many as 23 of the 50 signatories of the second letter are of Muslim majority. Among these, many stand out for diplomatic and cultural importance within the Islamic world such as Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Yemen. Turkey, undoubtedly the most influential actor among the Turkish-speaking populations of Central Asia and Xinjiang, didn’t sign the letter, but a few days before the discussion at the UN, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, during an official visit to Beijing, stressed that it was an undeniable “hard fact” that “residents of various ethnicities [are] living happily in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region thanks to China’s prosperity”, adding that “Turkey will not allow anyone to drive a wedge in its relations with China”60.

When, more recently, some major Western clothing companies such as H&M and Nike announced their intention to avoid purchasing cotton and other raw materials from Xinjiang in solidarity with the workers allegedly exploited in the fields, following the sanctions approved last March 22 by the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom and Canada for the alleged human rights violations committed in Xinjiang, Chinese consumers spontaneously announced a boycott of the brands in question, forcing the latter to back track61. Commenting on this episode in the press conference of March 29, the spokesman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, Zhao Lijian, argued that “there is no forced labour in Xinjiang” and that “cotton-picking is highly-paid work”, explaining that the data of the regional government shows that in 2020 70 per cent of all cotton were harvested mechanically, and that digital techniques are commonplace in the agri-food chain in Xinjiang and elsewhere62.

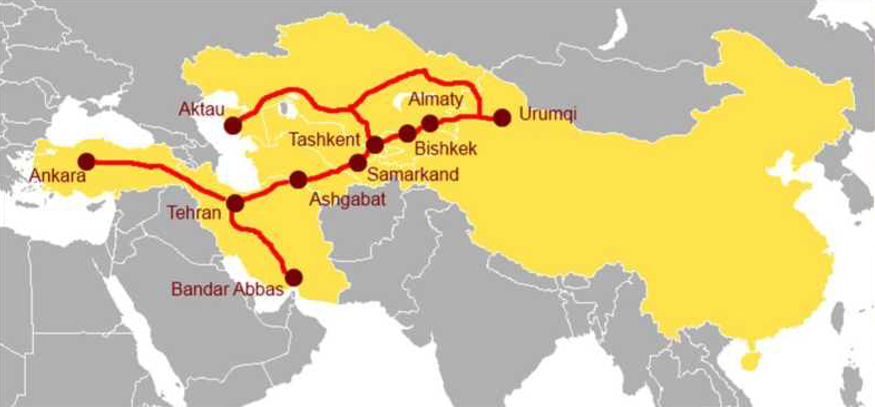

In his weekly briefing, Zhao also referred to a video of a lecture by US colonel Lawrence Wilkerson, now retired, posted on YouTube about three years ago, which recently gained the public attention for some important points that it raises in light of the international smear attacks against China. During his speech at the Ron Paul Institute, in 2018, colonel Wilkerson, chief of staff to former Secretary of State Colin Powell, said that that the US’ aim was to “destabilise China” by using Uyghur separatists to foment unrest in the region and push Beijing’s radius of action towards the inside63. As seen above, Xinjiang plays a strategic role in the Chinese logistics framework, confirming itself as a fundamental hub in the national infrastructure and logistics system, both in terms of freight transport and energy supply. The region thus takes on a very particular importance in the light of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which intends to reconstruct the ancient Silk Road routes in a modern key. Destabilising Xinjiang therefore would mean blocking this great project and, to do so, the United States and the governmental and non-governmental entities that support its global hegemony seem to have no qualms about exploiting the issue of human rights for their own geopolitical interests.

By virtue of its development, however, Xinjiang and the ethnic communities that have inhabited it for centuries now enjoy unprecedented opportunities and it is not difficult to believe, on the basis of the data collected in this report and other similar studies64, that what the Chinese local and national authorities say corresponds to the truth. The interview given in January 2020 to the Global Times by Kahar Abdurehim, the eldest son of Rebiya Kadeer, and by her young grandchildren Aydidar Kahar and Kedirye Keyser is emblematic: in the interview, where they are shown going about their daily life, at university and in the shopping malls of Urumqi, they deny that their family members are locked up in prison, as asserted by Rebiya Kadeer in some statements released from Virginia, where she has been residing for sixteen years now, and invited the grandmother, who left Xinjiang several years ago, to come and see with her own eyes how good life is in Xinjiang nowadays65.

Signatories

- Michael Dunford, Emeritus Professor of Economic Geography, UK.

- Marco Ricceri, segretario generale EURISPES, Roma, ITA.

- Daniela Caruso, professoressa di “Studi sulla Cina” Nazioni Unite-Università Internazionale per la Pace, Roma, ITA.

- Jean-Pierre Page, international writer, editor of “La pensée libre” www.lapenseelibre.org, trade unionist former member of the national leadership of CGT in France and head of its international dept, FRA.

- Thomas Fazi, independent journalist, writer, translator, Roma, ITA.

- Albert Ettinger, Ph.D., author, high school and college teacher, LUX.

- Adriano Màdaro, journalist, sinologue, Ph.D. of Journalism at the University of Communications in Beijing, curator of the Great Exhibitions devoted to “The Silk Road and the Chinese and Mediterranean Civilizations“, author of books and catalogues about History and Culture of China and Far East.

- Francesco Violante, Ph.D. in Storia dell’Europa moderna e contemporanea, ricercatore e docente di Storia medievale, Università di Bari “Aldo Moro”, ITA.

- David Castrillon, Research-professor, Universidad Externado de Colombia, Bogotá, COL.

- Maria Morigi, archeologa e storica, esperta di Storia delle religioni orientali. Ha condotto ricerche in Afghanistan, Xinjiang e Tibet. Trieste, ITA.

- Raffaele Valente, General Manager Southern Europe & Western Europe presso Roto Frank DachsystemTechnologie, Venezia, ITA.

- Beppe Grillo, fondatore del Movimento 5 Stelle, Genova, ITA.

- André Lacroix, author, retired teacher, BEL.

- Elisabeth Martens, biologist, writer and teacher, FRA.

- Jean-Michel Carré, Regista, Parigi, FRA.

- Maria Moreni, esperta di cultura cinese e di relazioni con la Cina, Presidente di Italy-China Link per la cooperazione tra le eccellenze dei due paesi.

- Andrea Turi, Presidente del Centro Studi Eurasia e Mediterraneo, CeSEM, Pistoia, ITA

- Enrico Vigna, giornalista indipendente, saggista e attivista per la pace, attuale portavoce per l’Italia del Forum Belgrado per un Mondo di Eguali, ITA.

- Michel Aymerich, créateur et auteur du blogue «A contre-air du temps», FRA.

- Vito Petrocelli, Senatore della Repubblica, Presidente della Commissione Affari Esteri del Senato.

- Gonzalo Tordini, Director of Sino-Argentine Strategic Program. National Defense University. President of Argentina China Alumni Association (ADEBAC).

- Prof.ssa Maria Francesca Staiano (PhD), Coordinatrice del Centro de Estudios Chinos, Instituto de Relaciones Internacionales, Universidad Nacional de La Plata (IRI-UNLP), Argentina.

- Laura Ruggeri, semiologa e saggista, Hong Kong

- Luigi Cecchetti, coordinatore dell’Osservatorio Italiano sulla Via della seta, sezione italiana del Silk Road Connectivity Research Center di Belgrado, IT.

- Tom Fowdy, political analyst, UK.

- Dr. Tamara Prosic, Monash University, AUS.

- Claudia Chaufan, Associate Professor, York University, CAN.

- Radhika Desai, Professor, University of Manitoba, CAN.

- Alan Freeman, co-director, Geopolitical Economy Research Group, Manitoba, CAN.

- Carlos Martinez, independent researcher and author, UK.

- Colin Patrick Mackerras, Professor Emeritus, Griffith University, Queensland, AUS.

- Marc Pueschel, journalist and editor for Junge Welt Berlin, GER.

- Dr Bruno Drweski, Member of faculty, Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) Paris, Centre de Recherches Europes Eurasie, Nanterre, Île-de-France, FRA.

- Antonis Balasopoulos, Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Cyprus, Cyprus, GRC.

- Tamara Kunanayakam, former Ambassador and permanent representative to the UN, Chairman of the UN intergovernmental working group on the right to development, Sri Lanka, LKA.

- Roland Boer, professor at Dalian University of Technology’s School of Marxism, Dutch and Australian citizen.

Notes

- Official Census, People’s Republic of China, 2018.↩︎

- Lev Gumilyov (1912-1992) was a Soviet historian, ethnologist and anthropologist. Born to the two famous Russian writers Nikolaj S. Gumilyov and Anna A. Akhmatova (the pseudonym of Anna Gorenko) in St. Petersburg, Gumilyov introduced the peculiar anthropological concepts of “ethnogenesis” and “passionarity”, studying the Eurasian region for decades and returning historiographical dignity to the peoples of Turko-Mongol tradition, largely incorporated into the Russian orbit between the 18th and 19th centuries.↩︎

- Zhang Qian (195-114 BC) was designated by the Han Dynasty to lead several exploratory missions in Central Asia. The goal of his travels, as reported in the 1st century BC Chinese historic chronicles Records of the Great Historian (Shiji) by Sima Qian, was to open the trade routes to the West, hitherto largely unknown, thus laying the foundations for the Silk Road. The Uyghurs did not populate these lands until the 6th century AD.↩︎

- According to scholars, the Uyghur term “Tdklimakan ” and the Chinese one “TdkOl日mdg^n ” could derive from the Persian “tark makan ”,meaning “place to stay away from”, or from the Turkish “taklar makan”, meaning “place of ruins”. In any case, the feeling of dismay and desolation aroused by that desert in the ancient local populations is evident in the historical chronicles.↩︎

- People’s Daily, “Oasis area keeps increasing in Xinjiang”, 6 August 2015.↩︎

- X. Li, Lo Xinjiang moderno. Armonia e sviluppo nel cuore dell’Asia Centrale, Anteo Edizioni, Cavriago, 2020, pp. 127-168.↩︎

- China.org.cn, “SCIO briefing on Xinjiang’s development”, 31 July 2019.↩︎

- J. Zhang, “A new provincial platform company in China for New Silk Road connections”, RailFreight.com, 4 September 2020.↩︎

- X. Li, op. cit., p. 26.↩︎

- Urumqi Airport, official data, 2019.↩︎

- Armin Vambery (1832-1915), the pseudonym of Hermann Bamberger, was a Hungarian historian, linguist and orientalist of Jewish origin. He travelled extensively throughout the territories of the Ottoman Empire, Persia and Central Asia, where he collected data, information and knowledge that enriched his studies. In 2005, as reported by Richard Norton-Taylor for The Guardian, the opening of the British National Archives revealed that Vambery had put his skills and travels to the service of the British government, working as a secret agent in the context of the Great Game, a political and diplomatic that saw the British and the Russians contend for zones of influence in Central Asia.↩︎

- In Central Asia, the ideological clash between Tsarism and Bolshevism never had clear-cut and well-defined contours as in European Russia, overlapping previous nationalist and sectarian impulses. This is the case of the Basmachi, rebels of pan-Turkic and pan-Islamic inspiration (with their own internal divisions) which emerged in the autonomous states of Central Asia (Alash Autonomy and Kokand Autonomy) during the Russian civil war (1917-1922). Led between 1920 and 1921 by the famous general Enver Pasha -former protagonist of the Revolution of the Young Turks in the Ottoman Empire, who fell in a firefight against the Red Army in a village a few kilometres from Baldzhuan, Turkistan SSR (now in Tajikistan) – the Basmachi continued the armed struggle until 1934, when their ambitions were definitively neutralised by Stalin.↩︎

- The reference is above all to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), an Islamist group founded in 1998 by extremist ideologist Tahir Yuldashev and former Soviet paratrooper Juma Namangani, with the stated aim of overthrowing Uzbek president Islam Karimov and creating an Islamic state based on the Sharia. After seventeen years of bloody attacks and armed clashes with the security forces in both Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, and active participation alongside al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, in 2015 the IMU officially affiliated with ISIS, a decision that resulted in an internal split. Born in the Fergana Valley, the movement gradually welcomed fighters not only from Central Asia but also from the Caucasus and the Middle East, which leads to exclude pan-Turkic influences.↩︎

- Jadidism (from usul ul-jadid or “new method”) was a political and cultural movement with a modernising and reformist orientation, which arose in the Muslim world of the Russian Empire between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. The intellectuals adhering to this movement tried to reconcile a progressive political vision with the Muslim traditions of the Turkic peoples. Opposed by the clergy and conservative sectors of the Turkic world, they were also the victims of government repression, since the Soviets didn’t accept the idea of establishing parties, nations or armies on the basis of religion. Their ideas came back into fashion after the collapse of the USSR, particularly in Uzbekistan.↩︎

- After having offered the Soviets for several years numerous areas for industrial production as well as oil and mineral extraction, Sheng Shicai asked them to leave Xinjiang, reconnecting with the Kuomintang and even executing numerous communists active in the region, including Mao Zemin, brother of Mao Zedong, future revolutionary leader. In the summer of 1944, however, Sheng again turned to Moscow, proposing himself as the president of a republic to be definitively incorporated into the Soviet Union. By now, however, Stalin had lost faith in Sheng and turned his letter over to the leaders of the Kuomintang, who removed him from office.↩︎

- The Taliban built a theocratic legal system based on the strict observance of Sunni Islam of Deobandi orientation, originating in northern India and Pakistan, but also on respect for Pashtunwali, an ancient code of conduct of the Pashtuns, the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan (around 42 per cent of the total population) and second-largest in Pakistan (15.4 per cent).↩︎

- B. Raman, “Explosions in Xinjiang”, South Asia Analysis Group – SAAG, 27 January 2005.↩︎

- The Guardian, “US removes shadowy group from terror list blamed by China for attacks”, 6 November 2020.↩︎

- US Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Leader of Group Tied to Al Qaida”, 20 April 2009.↩︎

- M. Gurcan, “How the Islamic State is exploiting Asian unrest to recruit fighters”, Al-Monitor, 8 September 2015.↩︎

- Ibid.↩︎

- Global Security, “East Turkestan Liberation Organization (ETLO) Eastern Turkestan Liberation Organization”, 7 September 2011.↩︎

- Radio Free Asia, Governance and Corporate Leadership.↩︎

- Ibid.↩︎

- M. Respinti, “‘Dozens of my In-Laws Vanished’. The Other 9/11 of Rushan Abbas”, Bitter Winter, 1 August 2019.↩︎

- The victims of the pan-Turkic and Islamic terrorism of Uyghur separatist organisations including numerous Muslims who are considered “apostates” or “traitors” for the sole reason of not adhering to Wahhabism. One of the most heinous murders is undoubtedly the one committed in 2014 against Jume Tahir, the seventy-four-year-old imam of the Id Kah Mosque in Kashgar, the largest in all of China, publicly accused for months by extremists of supporting the policies of the central government in the region [See BBC News, “Imam of China’s largest mosque killed in Xinjiang”, 31 July 2014].↩︎

- T. Branigan, “China locks down western province after ethnic riots kill 140”, The Guardian, 6 July 2009.↩︎

- C. Buckley, “China calls Xinjiang riot a plot against rule”, Reuters, 6 July 2009.↩︎

- See Human Rights Watch, “We Are Afraid to Even Look for Them”. Enforced Disappearances in the Wake of Xinjiang’s Protests, 2009.↩︎

- J. Saal, “The Islamic State’s Libyan External Operations Hub: The Picture So Far”, CTC Sentinel, Vol. 10, Issue 11, December 2017, pp. 19-23.↩︎

- A. Mattiello (edited by), Terrorismo di matrice jihadista: inquadramento concettuale e principali dinamiche geopolitiche, Servizio Affari Internazionali, Senato della Repubblica, Legislatura 17a – Dossier n. 6, 31 July 2015.↩︎

- RT, “US admits there is a much scarier terrorist group than ISIS”, 21 September 2014.↩︎

- The enlargement process, which began with the adoption of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) adopted by the SCO in June 2011 to regulate new entrants into the organization, completed its first long and complex phase on 9 June 2017, at the general summit in Astana (today NurSultan), sanctioning the full membership of India and Pakistan, two bitter geopolitical rivals, and for this reason was considered a huge diplomatic success.↩︎

- In the case of Azerbaijan and Armenia, the path still seems fraught with obstacles due to the mutual accusations between the two governments, but the resolution of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh in November 2020, which definitively sanctioned the return to Azerbaijan of the territories lost in the late 1980s, could open up new prospects for the two countries’ integration into the SCO..↩︎

- SCO, Shanghai Convention on Combating Terrorism, Separatism and Extremism, Art. 1, Shanghai, 15 June 2001.↩︎

- See T.M. Sanderson, “From the Ferghana Valley to Syria and Beyond: A Brief History of Central Asian Foreign Fighters”, Central for Strategic and International Studies – CSIS, 5 January 2018.↩︎