This very interesting article by Aaron Bastani, first published in Novara Media, takes on the dominant narrative around China and climate change – that China is largely responsible for the climate crisis – and highlights the extraordinary progress China has made in recent years in the fields of renewable energy, afforestation and low-carbon transport. Republished with permission.

One of the most striking statistics in grasping the speed at which we are transforming the planet is how China consumes more concrete every three years than the United States did in the whole of the 20th century.

Alongside the acceleration of how we use resources, this fact highlights the unique role China now plays in climate change. The world’s largest country, with a population greater than Europe and the Americas combined, has leapt into industrial modernity. This may be one of the most important events in human history, but it carries an immense ecological cost.

But does this mean China is now the world’s leading climate culprit? And should a nation like Britain, which accounts for just 1% of global emissions, even bother to undertake costly efforts to decarbonise when China, which accounts for 30%, is building coal power stations?

A complex picture.

China is easily the world’s leading polluter. But things are a little more complicated when trying to apportion blame for rising emissions and responsibility for any transition.

First is the obvious point: size. China is the leading producer of greenhouse gas emissions because it has a population of 1.4 billion. Measured per person, its emissions are only around eight tons, however, putting it behind the likes of Japan and the Netherlands. Meanwhile three anglophone countries – the US, Canada and Australia – emit twice as much CO2 per head, while Qatar emits four times as much.

Second is the issue of outsourced emissions – CO2 and methane produced by countries that manufacture products that are consumed elsewhere. Given China is by far the world’s leading manufacturer, accounting for almost 30% of global output, its carbon footprint must be understood in that context.

Outsourced emissions, which could be as high as 25% of the global total, cast wealthier, post-industrial countries in a more favourable light. One estimate places the UK’s CO2 emissions 50% higher when including goods manufactured overseas – an important point that is often missed when discussing its progress in reducing emissions since 1990.

Renewable energy.

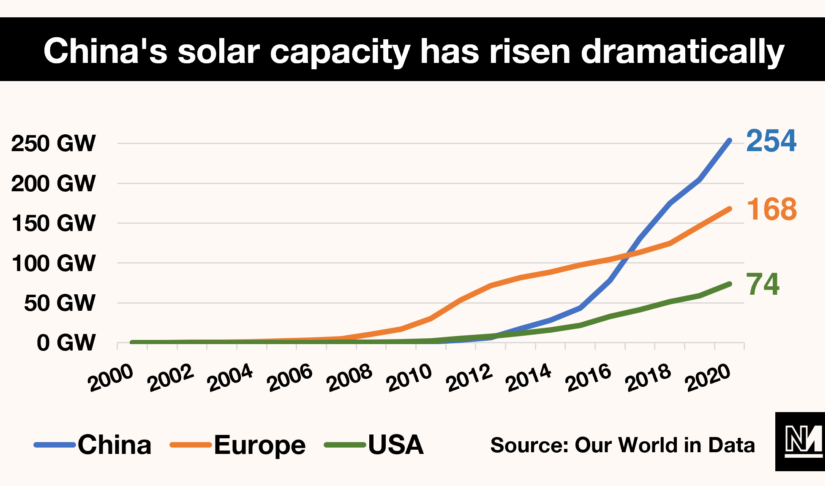

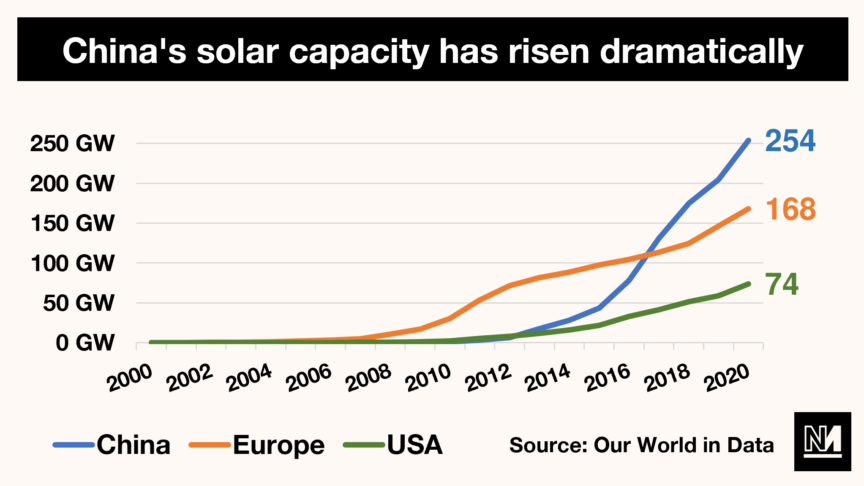

So China is the world’s leading polluter but, in a meaningful sense, it is nowhere near pariah status, with many critical countries having far higher emissions per capita. More interesting, however, is that despite only being as wealthy per person as Romania, the country is a world leader when it comes to renewable energy. In the area of solar energy, it now possesses more domestic capacity than Europe and the United States combined. What is more, this lead is accelerating.

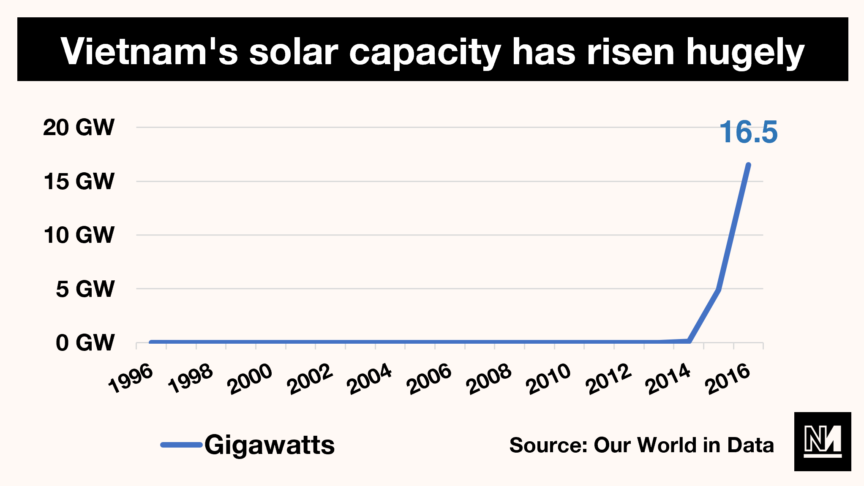

Chinese leadership in solar reflects broader shifts in Asia, with Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and India joining China among the world’s ten leading producers of solar energy. Perhaps most remarkable here is the story of Vietnam which not only posted economic growth in 2020, while experiencing staggeringly few deaths as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, but which also installed 9.3 gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity on rooftops alone – more than Germany, Italy and France combined. This pushed its national solar capacity to 16GW, meaning an increase of 3500% in just one year – the kind of advance activists demanding a green new deal in the US or UK can only dream of.

Similarly, South Africa installed more solar capacity in 2020 than Britain, France and Italy combined. This new reality, where countries with a lower level of economic development are beginning to outperform the global north, has China at its vanguard.

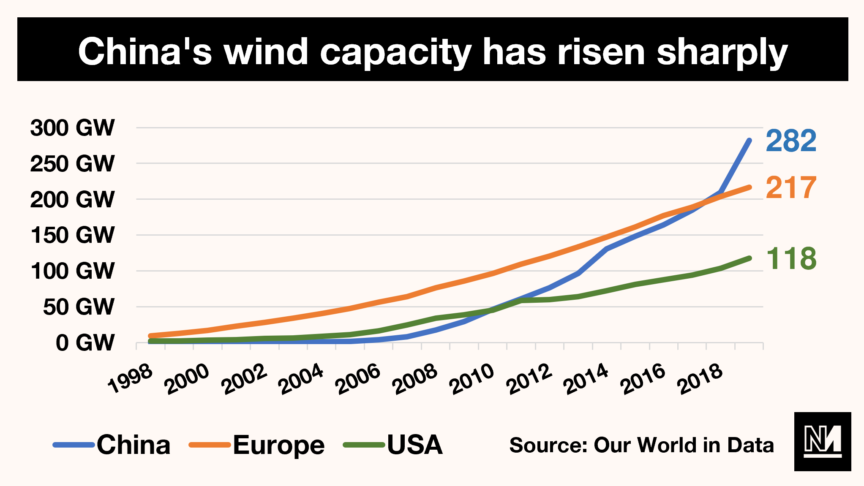

As with solar, China is the undisputed number one when it comes to wind power, producing more than twice as much as the United States. Again its leadership here is accelerating. China now has more than 500 terawatts (TW) of wind and solar capacity – with plans to more than double that to 1200TW by 2030. To build that kind of energy capacity in twenty years is extraordinary and without comparison in the global north.

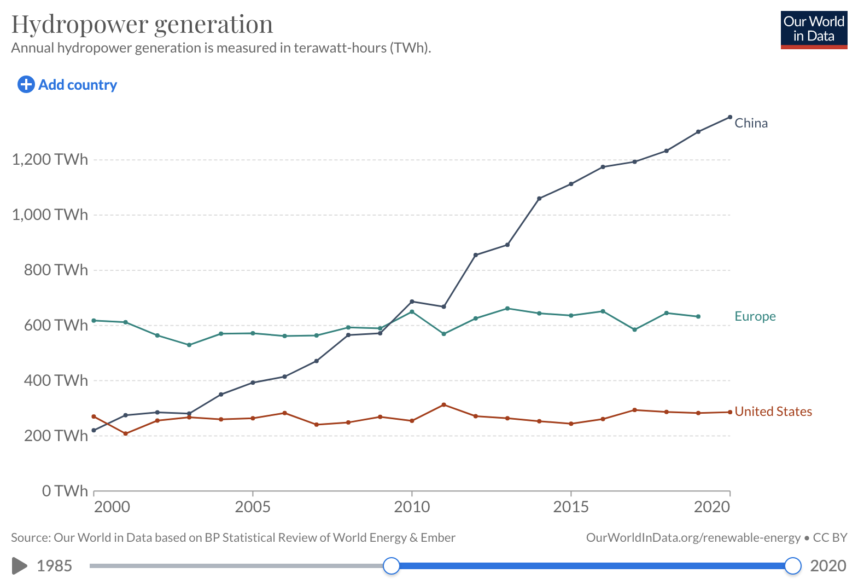

Finally, there is hydroelectric power, an often overlooked renewable – alongside geothermal – which plays a critical role for many countries. Here too China has attained singular dominance over the last decade. This is primarily a function of its large landmass and huge population, but it underscores how claims of it being a renewables laggard are without foundation.

It’s unsurprising, then, that Beijing expects energy from non-fossil fuels to reach 25% of total demand by 2030. Some observers expect that target to be met sooner given the present trajectory. Such a shift should, in theory, allow the country to reach peak emissions by the end of this decade, before its output begins to decline.

Beyond 2030, and with renewable capacity rising further, researchers from Tsinghua University have predicted that 90% of the country’s power should come from non-carbon sources by 2050, with the country’s ultimate ambition to be ‘carbon neutral’ a decade later.

Part of that strategy, alongside renewables, is the growth of nuclear power – which has seen an increase of 500% since 2010. During the 13th five-year plan, from 2016 to 2020, China built 20 new nuclear power plants, doubling national capacity to 47GW. The target before 2025 is 70GW and, according to China’s atomic energy research initiative, operational plants should reach 180GW by 2035. If that target is met it will mean China can produce more nuclear energy than the United States and France, Europe’s nuclear leader, combined.

How can you be clean with coal?

Despite its leadership in renewable energy, and a major expansion of its nuclear sector, China’s policy of building new coal-fired power plants, with 43 announced earlier this year, has attracted widespread criticism. While these new stations are predicted to add only 1.5% to the country’s existing emissions, they represent the latest wave of one of the biggest carbon events in history, with China building almost 600 coal-fired plants since 1992, the same year as the Rio Earth summit. At the heart of this gargantuan energy expansion has been the dirtiest fossil fuel of them all – and with full knowledge of the ecological consequences.

That Beijing is resisting calls to entirely abandon coal is instructive, because while the country is eager to pursue ‘green growth’ – and has a geopolitical and economic interest in becoming a post-carbon leader – such a mantle can’t be acquired at the cost of lower GDP, even if that means new plants quickly become stranded assets. Building new coal capacity need not fatally undermine Chinese ambitions for net-zero by 2060, but it does signal that in a choice between growth and decarbonisation the former will always triumph. In the event of a major downturn, it’s easy to see Beijing sticking with fossil fuels for far longer than presently planned.

When it comes to coal abroad, where China is the world’s largest investor, the picture is considerably brighter. Earlier this month it pledged to end the financing of overseas plants, a decision which could eliminate as much as 200 million tonnes of CO2 every year. Given similar announcements recently made by South Korea and Japan, the world’s largest public financiers of overseas coal appear to be turning off the taps.

Low carbon transport.

While China’s energy record over the last twenty years is mixed, an inarguable success is its leadership in low carbon transportation. Its 37,900km high-speed rail network, accounting for some two-thirds of all high-speed capacity globally, has been built in just 14 years, with another 32,000km under construction. That has led to something that would be unthinkable in the United States, Brazil and Canada: the demise of internal domestic flights. Passenger numbers on China’s high-speed trains have seen 30% annual growth since 2008, and a recent paper claimed that by 2025 80% of the country’s aviation routes would be overlapped by high-speed rail alternatives. This has already had profound consequences for domestic aviation, with the route between the cities of Zhengzhou and Xi’an, for example, being cancelled within two months of a high-speed rail connection opening in 2010. The United States, by comparison, has less high-speed connectivity than Uzbekistan (where it has been financed by, you guessed it, China) and could soon fall behind Iran, despite the latter being subject to some of the most brutal sanctions in history. In this regard, the US is far from unique, however, with Canada and Australia – two other high-emitting countries per head – also having built no high-speed rail at all.

It’s a similar story with urban transportation, with mainland China possessing 41 metro systems – around five times more than the US. This correlates with population size, but a key difference is that while China has another dozen systems under construction, and dozens more expected in the coming decades, the US mainland hasn’t laid new underground tracks for almost 30 years.

Reforestation.

China’s programme of reforestation has seen the country’s forest coverage increase from 12% in 1978 to 23% today. Beijing’s current plan is to plant 36,000 square kilometres of forest annually until 2025, more than the total area of Belgium, with the target for 2050 being forest coverage of 30%.

According to Nasa this unprecedented programme of greening, estimated to have cost more than $100bn since the late 1990s, is the principal reason that the Earth is now greener than it was twenty years ago.

While far from a panacea, planting 900 million hectares of forest on degraded land, approximately a trillion trees, might store the equivalent of 25% of atmospheric carbon. What is more, China’s reforestation programmes – involving around 20% of the country’s rural population – have played a major role in cutting rural poverty, as well as helping with soil retention, flood mitigation and desertification.

As with any project on such a scale, there are criticisms. One is that industrial-scale reforestation consumes too much water – a precious resource in the 21st century. Another, accepted by Beijing, is that greater coverage has generally been the result of monocrops, meaning a negligible change in biodiversity. This approach has also meant many trees themselves die: within 25 years of the Great Green Wall initiative starting in 1978, most of the trees were dead or dying. Lessons appear to have been learned, however, particularly with the nation’s proposed ‘Millenium forest’.

Despite the drawbacks China, as with so much else, is in a league of its own. And once more its achievements are in stark contrast to the US, where reforestation efforts fail to even keep pace with ever more frequent wildfires.

China is now responsible for an astonishing volume of emissions. Yet it is also a renewable powerhouse, accounting for around 50% of the world’s growth in renewable energy capacity last year. It is number one in areas like lithium-ion batteries, solar and wind while having a higher percentage of cars that are electric than the US, EU or UK. It possesses two-thirds of the world’s high-speed rail capacity, something which has critically undermined domestic internal flights, and has unprecedented urban connectivity. All this in a country which, on a per head basis, is as wealthy as Romania.

And yet, for all that, it faces a mammoth task if global emissions are to plateau. Net-zero by 2060 is an impressive ambition, particularly when placed alongside the more meagre aims of many in the global north, yet it is almost certainly insufficient to avoid warming beyond 1.5 degrees this century.

The debate in the West about whether China is a climate leader or not can be decisively answered in the affirmative – despite the regularity with which the country is presented as a fossil fuel bogeyman. The real question, however, is whether the world’s rising power is willing to accept lower economic growth, and a break on its geopolitical ambitions, to avert runaway climate change this century. Despite their highly public criticisms of China, this is something political elites in the Global North avoid at all costs, because their priorities – of economic growth over planetary survival – are no different. Yet even within those fixed parameters, of myopic ambition over long-term ecological planning, their record is depressingly pedestrian when compared to China.