In this short video from CGTN, Betty Bar and her husband George Wang discuss their experiences living in Shanghai, from the 1930s up to the present. They remember the intense poverty in the city before liberation; the horrors of the Japanese occupation; the professional, disciplined and people-oriented nature of the People’s Liberation Army when entering Shanghai; and the extraordinary improvements in people’s lives in the ensuing decades. George Wang comments: “Without the Communist Party, without Mao Zedong, what would our life be today?”

Category: Interviews

Li Jingjing interviews Medea Benjamin from CODEPINK on US militarism, China’s poverty alleviation, and the New Cold War

Embedded below is a very interesting and useful interview by Li Jingjing (for CGTN) with CODEPINK co-founder Medea Benjamin. They discuss CODEPINK’s history of opposing US militarism, PBS’s shameful censoring of the documentary ‘Voices from the Frontline: China’s War on Poverty’, the China is Not Our Enemy campaign, and the dangers of a New Cold War.

Rania Khalek interviews Daniel Dumbrill on Xinjiang, Hong Kong, poverty alleviation and the New Cold War

This excellent interview appeared on BreakThrough News on 30 August 2021. Rania and Daniel cover some crucial topics related to the propaganda war against China.

Note that Daniel Dumbrill is among the speakers at our webinar on 9 October – The Propaganda War Against China – along with Chen Weihua, Li Jingjing, Ben Norton, Danny Haiphong, Jenny Clegg, Michael Wong, Radhika Desai and Kenny Coyle.

Danny Haiphong on the China-Africa ‘debt trap’

Interviewed by Rania Khalek for the Unauthorized Disclosure podcast, Friends of Socialist China co-editor Danny Haiphong explodes the myth of Chinese ‘imperialism’ in Africa, tracing the roots of the China-Africa relationship in the early period of the People’s Republic and the shared values of anti-colonialism and Global South solidarity.

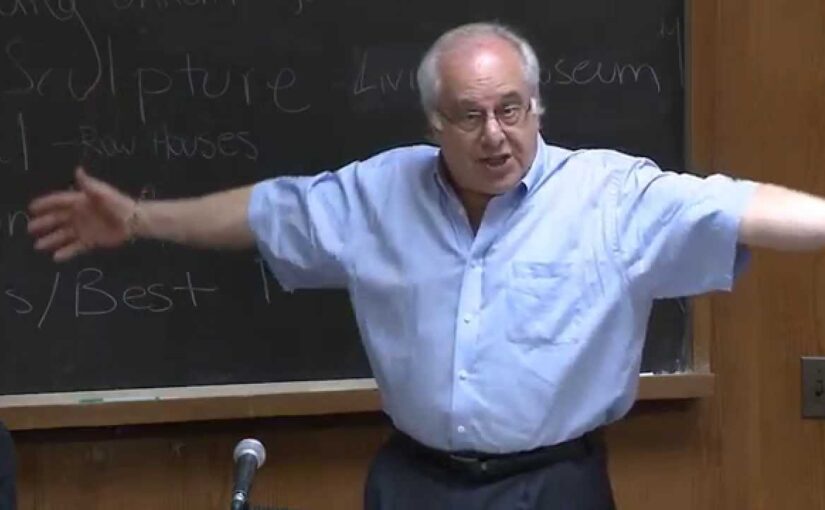

Richard Wolff on China’s rise to global prominence

We are republishing this very interesting interview with Marxist economist Richard Wolff in Beijing Review, in which he discusses the reasons behind China’s economic success and the motivations for the US-led New Cold War.

On CPC-induced synergy

The first book I ever read about China was The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, presenting the stories of poverty and suffering across the Chinese countryside in the early 20th century. What she described in the book actually didn’t take place too long ago, but when you look at what China has achieved over the past years and then compare it to what Buck wrote about, it makes for an incredible feat.

Since 1949, when the communist revolution succeeded, U.S. foreign aid did not go to China because the latter was a socialist country. U.S. foreign aid was, however, dispatched to every other Third World country across Asia, Africa and Latin America. Nevertheless, China has done better economically than every other country that did receive the assistance.

What does that tell us about getting aid from the West? It’s not the path to economic growth, it never was. The reality is that the path to economic growth was not to take aid from the West, but to rely on yourself. The Soviet Union once helped China, before the 1960s, but in general, the Chinese achieved it mostly by themselves. That’s a very powerful message all over the world.

Continue reading Richard Wolff on China’s rise to global prominenceInterview with the Editor of ‘Waiting for Dawn: 21 Diaries from 16 COVID-19 Frontlines’

We are republishing this interview with Leijie Wei, editor of the book ‘Waiting for Dawn: 21 Diaries from 16 COVID-19 Frontlines’ and academic at the School of Law, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. It provides valuable insight into China’s public health system and the social, economic and political structures that allowed China to very quickly and effectively contain the Covid-19 pandemic.

The interview was conducted by Shuoying Chen (Academy of Marxism, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), and was originally published in World Review of Political Economy, Volume 11, Number 4, Winter 2020. Republished with permission.

ABSTRACT

Waiting for Dawn: 21 Diaries from 16 COVID-19 Frontlines takes a global perspective, examining the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on governments and the public around the world. The editor of the book believes that the reasons why mandatory tracking, testing and quarantine measures have been effectively implemented in China center on the unified leadership provided by the Communist Party of China (CPC); the active response by state-owned enterprises and institutions; and the full trust of the majority of the public in the government’s anti-pandemic measures. In an effort to win elections, meanwhile, politicians in Europe and the United States are politicizing the pandemic and making China a scapegoat. In contrast to socialist China’s policy of ensuring all those in need are hospitalized with free testing and treatment, the essentially capitalist public health models applied in most Western countries have brought more concrete and explicit class conflict, and the drawn-out pandemic in the West has exacerbated various forms of social injustice. The COVID-19 epidemic is a reminder that a country’s governance ability should not be judged on the basis of simplistic conceptions of democracy, and that the needs of Mother Earth must be considered in the collective building of a community of shared future for humankind.

Shuoying Chen (SC): To begin with, how did you come to the idea of producing a collection of diaries from different countries around the world?

Leijie Wei (LW): In 2020, China faced a very dangerous first few months, but through the efforts of the whole nation, it achieved an epic reversal. The global pandemic began in February when the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) broke through the threshold of extraterritorial spread, and the world then fell gradually into the “darkest moment” of the pandemic. Since that time, we have had to rethink COVID-19 from a global rather than a local perspective, taking account especially of how other countries are different from or similar to China in terms of their experience of fighting the pandemic. With that in mind, I invited 21 contributors from 16 countries to document the lives during the pandemic of people around the world, recording what they have seen, heard, felt and understood during this period, with various narrative perspectives and in the form of diaries. Various pandemic diaries kept by Chinese people in quarantined cities, based on personal experience and with a strong literary flavor, undoubtedly have their value. Nevertheless, their unidimensional focus on a single area and lack of a multi-dimensional comparative perspective may lead to narrow and idiosyncratic accounts. This collection, entitled 21 Diaries from 16 COVID-19 Frontlines, covers 16 countries on four continents, including Asia, Europe, North America and South America. The authors are from various social backgrounds and differ in their social status. With its multi-dimensional and global perspective, the collection offers particular promise as a way of examining the impact of COVID-19 on different governments and populations, and as a history of everyday life in the age of the pandemic, it will also serve in future years as a first-hand account of this unforgettable experience.

Continue reading Interview with the Editor of ‘Waiting for Dawn: 21 Diaries from 16 COVID-19 Frontlines’Michael Crook in conversation with Dr Frances Wood

In this interesting video of a webinar organised by our friends in the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding (SACU) the distinguished Sinologist Dr Frances Wood discusses with Michael Crook about his family’s long connection with China, the Chinese cooperative movement and some of the many British people who supported and helped the Chinese revolution.

Michael was born and brought up in China. He is the son of David and Isabel Crook, communists, internationalists and staunch supporters of the Chinese revolution. Born in 1915, Isabel still lives in Beijing. In 2019, President Xi Jinping awarded her the Friendship Medal of the People’s Republic of China. Among the small number of other recipients was Cuban revolutionary leader Raúl Castro.

Interview with Carl Zha on the 100th Anniversary of the Communist Party of China

Friends of Socialist China co-editor Danny Haiphong interviews Carl Zha, political analyst and host of the popular Silk and Steel podcast, to explain the underlying reasons for the Communist Party of China’s widespread popular support. The interview appeared first on the Black Agenda Report presents: The Left Lens Youtube channel.

Eric Li on the continuity between Mao-era and reform-era China

Shanghai-based political scientist Eric Li was interviewed on RT’s Going Underground show, about a number of topics. We reproduce the video below, along with some key excerpts from the transcript.

On the basic continuity between pre-1978 and post-1978 China

Since the Cold War, China is the only major country that has really prospered and delivered for a large number of people – delivered to them a better life.

This was not because China abandoned socialism. Some people misconstrue the history of modern China; they tend to divide it into the first 30 years under Mao, until the late 1970s and Deng Xiaoping’s market reform, which took China to what it is today. But I’ve always said that without the first 30 years, the market reforms would not have been possible.

In the first 30 years, obviously, we had a lot of problems and a lot of mistakes. But it was in the first 30 years that we took our life expectancy – which in 1949 was about 40 – to 67 in the late 1970s. Literacy rate went from negligible to just over 80%, 100% among young people, in the late 1970s. Industrial base was built in the first 30 years, and more importantly, national independence, because China acquired nuclear weapons so nobody could invade it. That allowed it to pursue its own path after the first 30 years of the People’s Republic.

So Deng Xiaoping’s reforms were successful, in many ways, because the foundation was laid in the first 30 years.

On whether China is a capitalist country

We don’t have capitalism. We have a market economy, we do have capital and we have people like me who manage capital. A market economy means that you manage capital in a way that it generates efficient returns, you allocate resources efficiently. Capitalism to me means the interests of capital rise above the interests of the society as a whole. And capitalists capture the political system for their own benefits. And that we don’t want in this country.

On the shift in China’s priorities over the last decade

We’ve seen a great transformation of China in the last 9 to 10 years. I think the paradigm shift occurred in 2012, with the 18th Party Congress. China shifted from the 30 or 40 years prior to that, which was the headlong pursuit of economic growth, at whatever the costs. And we’re shifting away from that and towards more balanced growth, or more balanced development, which really means common prosperity, so a more equitable society.

There are a lot of side effects of market economics that we had pursued. Inequality is one of them, environmental degradation is another, and corruption was another. So all these issues needed to be addressed. And I think there has been a great transformation within Chinese society and China’s self perception, and the national aspiration of the Chinese people. Especially among young people. In my generation, we were primarily concerned about China being poor and lacking development. But if you ask the younger generation, born post 1990, of course they want economic opportunities, but their primary concerns are about inequality, and sustainability for the future.

Interview on the ‘Uyghur Tribunal’ and the media war against China

Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez was interviewed on the World Today podcast by Anna Ge, on the subject of the ‘Uyghur Tribunal’ and the latest round of accusations regarding China’s treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

The segment is embedded below, along with a transcript.

Anna:

You’re listening to World Today. Some Western media outlets have started hyping another report wrote by the infamous anti China activist Adrian Zenz. The report claimed there will be millions fewer Uyghurs and other ethnic minority newborns in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the next 20 years. But how did he come to this sensational conclusion, how reliable is his study? To delve into these questions and more, we’re joined by Carlos Martinez from London. He’s an author and activist. Thanks for joining us, Carlos. So first of all, how much faith can we put into this report based on the data samples and methodology Zenz used?

Carlos:

So there are two things that we need to look at here. One is the data samples and methodology, the actual scientific validity of the study. And the other is the way that it’s reported. Because for the vast majority of people that see this study, they’re going to see the headlines, they’re going to see maybe a few sentences from an article, they’re not going to take a close look at the data.

Now, in terms of the methodology, Adrian Zenz has really honed this method over the course of several years. He gets lots of data from lots of places, he throws it all together. And then he tries to find the subset, the small piece of that data, that seems to prove what he wants it to prove, his hypothesis. And that’s a classic technique that people use to lie with statistics, to make statistics work for them. The correct scientific approach is to analyze all the data you have, and see if it confirms your hypothesis or not, not to narrow the sample down in a very specific way, until the data tells the story you want it to.

An equivalent example might be, maybe I’ve got a hypothesis that people read more books than they used to 10 years ago. So I start by asking a random sample of 100 people: how many books did you read 10 years ago? And then I go and stand outside a bookshop or a library and ask another 100 people, how many books did you read this year? Obviously, the average is going to be higher now, but not because 10 years have passed, but because I’ve selected the sample that’s going to give me the answer that I want. And this is what Zenz has done, essentially, he has narrowed in on a very small subset of data for one year, in a section of Xinjiang, in southern Xinjiang. And on the basis of that data, he projects that the population growth rate will reduce by 1/3.

But then, his study gets blanket coverage in the Western media. And the headlines also, that the Uyghur population number is going to reduce by 1/3. Now to cut actual population numbers by a third in 20 years, not only do you have to stop anybody from having children, but you also actively have to kill a few million people on top of that. So the whole thing is just ludicrous and unbelievable.

The population growth rate might be declining somewhat. But that’s actually the case throughout China for a number of reasons including urbanization, people joining the workforce, people going into higher education and so on. But actually we’ve seen that over the last decade, the Uyghur population in Xinjiang increased by 25% compared to the Han population, which increased by just 2%. So this latest study from Zenz is really just something that really be ignored but in fact is being given blanket media coverage in the West and is feeding into this overall story that we have of China committing a genocide or a cultural genocide in Xinjiang.

Anna:

You have visited China before. What is your impression about China and Xinjiang? Is there a gap between Xinjiang in western media and in your personal experience?

Carlos:

Yes, I would say there’s a big gap. I went to Xinjiang, specifically to Urumqi, in January last year. In terms of my expectation, going on the basis of what I had seen in the Western media before I went, I thought I would witness the intense repression of Uyghur Muslims. I didn’t think that I would see Uyghur people and other ethnicities living ordinary lives, engaging in their customs, engaging in their traditions. But actually, that’s exactly what you do see in Xinjiang. I mean, the group I was in, we didn’t have an official guide. We weren’t being told where to go by a CPC or government official. We walked around freely. We saw mosques everywhere. We saw many hundreds of Uyghur Muslims wearing distinctive clothing, walking, working, and definitely not seeming like they were in fear of being persecuted. In fact, you go to the central area and you see many people, especially older people dancing outside to traditional Uyghur music. We ate in Uyghur restaurants, the food was halal, there was no alcohol available.

All the street signs have both Chinese and Uyghur writing, one sees newspapers, one sees magazines in Uyghur script, so the feeling I got was one of not just ethnic diversity, but also of harmonious relations. If I compare it with Australia, which is a country that I’ve visited several times, the indigenous population in Australia is an oppressed minority who are prevented from living their traditional ways of life, who suffer from a much lower life expectancy than the rest of the population, from much lower educational attainment and outcomes, much higher prison rate and so on. If you go to an Australian town, any Australian town really, you can see that the situation for indigenous people there is disastrous. And the state, the government does very little to help those people. And there is ethnic conflict rather than ethnic harmony. It would be unusual for example, if I went into a cafe in Brisbane, to see a European-Australian and an Indigenous Australian, working together or having, you know, a normal friendly relationship. But it wouldn’t be at all unusual in Urumqi or Kashgar to see a Uyghur person and a Han person working together and being friends.

So yes, I would say in terms of the what I see about Xinjiang in Western media and my personal experience, there’s an enormous gap.

Anna:

It seems that China’s Xinjiang has increasingly become a card played by the West. Recently, China has dismissed a so called Uyghur tribunal set up in the United Kingdom, to hear allegations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang. What do you make of the legitimacy of the tribunal and the motivation behind it?

Carlos:

Well, I think it’s fairly clear that the so called tribunal has got no basis in international law. It’s part of an ongoing and quite wide ranging and long term propaganda campaign. And in turn, it’s clear that propaganda campaign is part of a US led New Cold War project, which is, is pretty well known that it’s designed to slow down China’s rise, and to try and maintain a unipolar world in which the US leads, in which the US enjoys hegemony, in which the US can structure international relations in order to serve the interests not of humanity but its own interests. If China keeps growing, and it keeps promoting and pushing a system of multipolarity, which is a more democratic framework of international relations, then the US doesn’t get to impose its will on the world any more.

China’s economy is growing, right? China has wiped out extreme poverty, China has shown that it can deal with a huge threat like the pandemic, China is taking the lead in trying to prevent climate breakdown, which is the number one threat facing humanity. And is actually the sort of thing where, in the West, we like to think we’re in charge of dealing with climate breakdown, because we’re more civilized, we’re more enlightened than the rest of the world. But actually, China’s taking the lead on that. And every success that China has is a sort of ideological blow to this capitalist or neoliberal orthodoxy. So that’s really why the US and its allies are obsessed with slandering China, making it look bad, trying to prevent other countries from working with it, trying to slow down its rise, trying to cut it out of of global value chains, trying to prevent it from having access to certain raw materials, and elements of technology, and so on.

The Uyghur tribunal fits into a more generalized setup of information warfare that the US and its allies are waging against China.