For the last nearly six months, a landmark exhibition at the National Museum of Australia in the capital Canberra has been reminding visitors that Indigenous-Chinese bonds helped forge the links between the two peoples long before the two countries established diplomatic relations in 1972.

Our Story: Aboriginal–Chinese People in Australia, is the fruit of a five-year research project led and curated by Chinese-Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping and shows how mixed heritage communities wove ties of survival and solidarity on nineteenth century goldfields and in pearling camps. Drawing on historical records and oral histories, Our Story challenges monolithic accounts of Australian history.

During the gold rushes and in industries such as pearling, railways, and agriculture (1850s–1900), Chinese labourers settled across northern Australia and many formed relationships with Aboriginal women, in the face of the White Australia policy and other racist legislation that targeted both peoples.

These families blended Chinese traditions – language, cuisine, festivals – with Aboriginal kinship and cultural practices. “I’m Aboriginal, but I’m also proud of my Chinese heritage,” says Peter Yu, whose family photographs in the exhibition tell the story of how his Hakka father and Yawuru mother raised nine children under restrictive cohabitation laws, similar to those of apartheid South Africa.

Survival often demanded ingenuity. In the 1930s, Wen Liqun registered her Larrakia stepson – her Chinese husband’s son with a Larrakia woman – as “Chinese” to shield him from the Stolen Generations. (According to Wikipedia: “The Stolen Generations [also known as Stolen Children] were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church missions, under acts of their respective parliaments. The removals of those referred to as ‘half-caste’ children were conducted in the period between approximately 1905 and 1967, although in some places mixed-race children were still being taken into the 1970s. Official government estimates are that in certain regions between one in ten and one in three Indigenous Australian children were forcibly taken from their families and communities between 1910 and 1970. The Bringing Them Home Royal Commission report [1997] described the Australian policies of removing Aboriginal children as genocide.”)

In the article published below, which was originally published on the website of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, Dr. Marina Yue Zhang, an associate professor at the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney (UTS: ACRI), writes:

“As the exhibition prepares to tour China in 2026, it forces a reckoning: how does a nation reconcile its suppressed histories with its multicultural present? By reconnecting with these hidden roots – embodied in everyday objects and intimate stories – Australia may yet forge its most resilient, relational partnership with China and its people.

“‘In an age of tariff wars and tech sanctions,’ says Dr. Jilda Andrews, curator of the museum, ‘Our Story isn’t just an exhibition. It’s a milestone in putting First Nations voices at the centre – creating a space for truth-telling, listening and honest conversation.’”

As the exhibition prepares to move on to China next year, readers in Australia still have until 27 January 2026 to see it at Canberra’s National Museum of Australia.

As Australia marked Reconciliation Week (27 May – 3June ), a landmark exhibition at the National Museum of Australia reminds us that Indigenous–Chinese bonds helped forge the links between the two peoples long before Canberra and Beijing formalised diplomacy in 1972.

Our Story: Aboriginal–Chinese People in Australia, a five-year research project led and curated by Chinese-Australian artist Zhou Xiaoping, uncovers a legacy of resilience and cultural fusion. Mixed-heritage communities—unwitting pioneers of people-to-people diplomacy—wove ties of survival and solidarity on 19th-century goldfields and in pearling camps. Drawing on historical records and oral histories, their stories—Our Story, the untold narratives of the nation—challenge monolithic accounts of Australian history and reveal a premodern form of “soft power.”

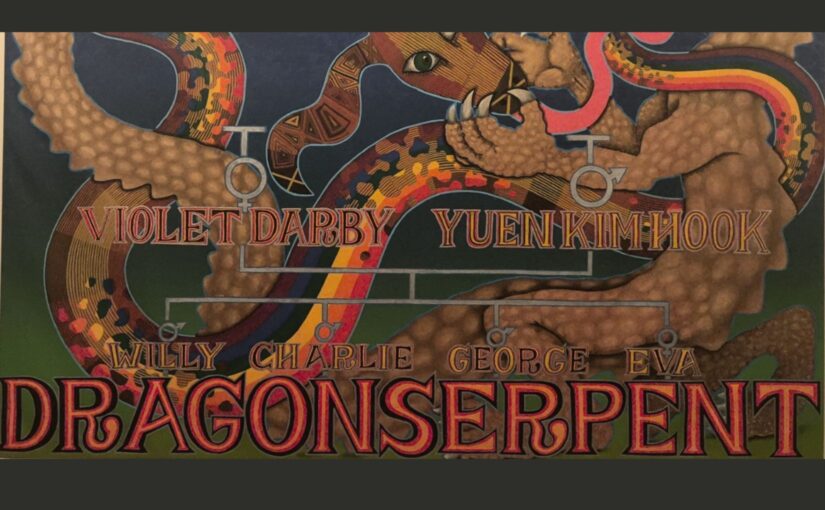

Through videos, installations, and embedded texts in family trees and photographs, the exhibition invites contemporary Aboriginal artists to interpret these “our stories.” Together, they illuminate the accidental diplomacy of Chinese men and Aboriginal women who built communities against the odds.

Continue reading First Nations and Chinese migrant workers pioneered Australia-China people-to-people links