With the Trump administration’s increasingly aggressive tariff measures, economists are warning of the risk of an international trade war, with the US and China as its major antagonists. To provide some much-needed clarity on this issue, we are pleased to republish below two recent articles from British Marxist economist Michael Roberts.

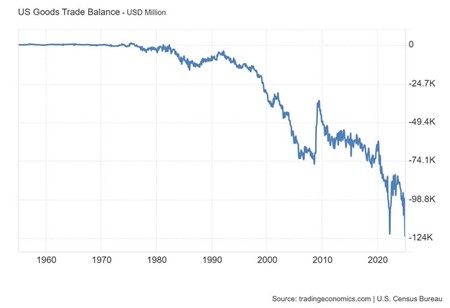

Michael describes the core of Trump’s tariff strategy as aiming to “make America ‘great again’ by raising the cost of importing foreign goods for American companies and households and so reduce demand and the huge trade deficit that the US currently runs with the rest of the world”. According to the US government, this will boost incomes and jobs in the US. Furthermore, the extra tariff revenues will boost Treasury coffers, supporting the administration’s plan to cut income tax and corporation tax.

What will the actual effect of the tariffs be? Michael argues that the tariffs will not reduce the US trade deficit, but will instead raise prices for US consumers and reduce the competitiveness of US companies. Inflation will rise, taxes will be cut, federal spending will be gutted – meaning that the consequences for the US working class will be dire. At a global level, “increased tariffs and other protectionist measures by all sides in retaliation will weaken world trade and economic growth. World trade growth showed some recovery in 2024 after contracting in 2023. Trump’s tariffs will stop that recovery in its tracks.”

Countering those economists who argue that tariffs have always been a valuable tool for nurturing domestic industry, Michael writes: “The US in the 21st century is not an emerging industrial power that needs to protect burgeoning new industries from powerful competitors. Instead, it is a mature economy with a declining industrial sector that will not be restored in any significant way by tariffs on Chinese or European imports.”

Further:

American capital did not invest to sustain its manufacturing superiority because the profitability of that sector had fallen too mcuh. Instead, they switched to investing in financial assets and/or shifting their industrial power abroad. In the last couple of decades they hoped to sustain an advantage in hi-tech and information technology including AI. Now even that is under threat. But this is not the fault of China running an ‘unfair’ industrial trade policy that is based on suppressing the living standards of its people; on the contrary, it is the failure of US capital to sustain its hegemony, just as Britain did in the late 19th century.

The two articles were first published on The Next Recession blog.

Trump’s tariff tantrums

Feb. 4 (The Next Recession) — Over the weekend President Donald Trump announced a batch of tariff increases on US imports of goods from the closest partners of US trade, Canada and Mexico. He proposed a 25% rise in tariffs (with a lower rate for oil imports from Canada). Then he announced a 10% rise in tariffs on all Chinese imports. Thus Trump started his new trade war.

And yet as soon as he started it, he stepped back. Trump announced that he was postponing the tariff increases with Canada and Mexico for a month because their governments had agreed to do something about the smuggling of fenatyl drugs into the US, which he claimed was killing 200,000 Americans every year. This figure is nonsense, of course, because under 100,000 Americans die from drug overdoses from all chemicals each year. As it is, the smuggling of fenatyl over the US-Canadian border is miniscule – certainly compared to the drug cartel operations on the Mexican border. Moreover, as Mexican President Sheinbaum pointed out to Trump, the cartels are able to operate their violent methods because of gun running operated by Americans in the US.

The Canadian and Mexican governments rushed to do a deal with Trump, promising batches of troops on the borders to stop trafficking and more joint anti-drug forces with the US etc. This seems to be enough for Trump to postpone his tariff move, although the tariffs on China will go ahead (no drugs there?). Also small package imports that have been free of import tax up to now will be brought into the customs system – and that will hit internet online purchases made by Americans for goods from abroad.

So what are we to learn from these shenanigans? Are the threatened tariff increases merely being used to browbeat other countries into concessions to Trump? Or is there a coherent economy policy in all this?

There is method in this madness. On the external front, Trump aims to make America ‘great again’ by raising the cost of importing foreign goods for American companies and households and so reduce demand and the huge trade deficit that the US currently runs with the rest of the world. He wants to reduce that and force foreign companies to invest and operate within the US rather than export to it.

He reckons this will boost incomes and jobs for Americans. And with the extra tariff revenues, the government will have sufficient funds to cut income taxes and corporate profit taxes to the bone (indeed, Trump says he wants to abolish income tax altogether). If this is the plan, then the tariffs will eventually be applied fully, with China probably getting an even bigger increase.

If Trump follows through with his protectionist tariff measures, what will be the impact on trade and the US economy? The current planned tariffs would affect $1.3trn worth of US trade, with 43% of all US imports affected.

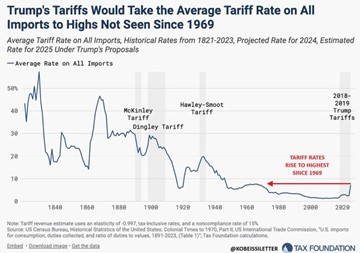

The accumulated increases in tariffs since Trump first launched them in his 2016-20 term would reach levels not seen since 1969, just before the international tariff reductions of GATT and the WTO during the ‘globalisation’ decades of the end of the 20th century.

In effect, tariffs are a tax on imported goods, which the US treasury can pocket. A 25% tariff on Canada and Mexico would raise costs for US automakers. This tariff is set to add up to $3,000 to the price of some of the 16 million cars sold in the US each year. Food costs would rise as well, with Mexico supplying over 60% of fresh produce to the US.

The precise impact will depend on how long the tariffs stay in place and if other countries retaliate. Already China has announced a series of counter-measures. China’s commerce ministry said the country would impose export controls on tungsten, tellurium, ruthenium, molybdenum and ruthenium-related items; essential components in tech products. China is also planning a 15% levy on liquified natural gas.

Within the US, if the tariff increases are followed through, domestic prices will rise and there will be upward pressure on inflation. There is a counteracting factor. If the US dollar increases in strength against other trading currencies, then the dollar cost of imports will be lower, reducing the price impact of the import tariffs. But most likely, the US inflation rate will head upwards. Inflation is already starting to rise again. Tariff increases will send the rate above 3% in 2025.

A US ‘think-tank’, the Tax Policy Center, estimates that the average American household’s after-tax income will fall 1%, or $930, by 2026 if the tariffs are fully implemented. That’s because consumer prices would rise by 0.7% and real GDP would lose 0.4%. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates tariffs will leave the US economy about 0.25% smaller next year and 0.1% in the long run. “The policies he’s pursuing have a high risk of inflation,” said Adam Posen, director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics think-tank. “It seems that promoting manufacturing and beating up US trade partners are goals that, for Trump, are a higher priority than the purchasing power of the working class.”

Trump claims that the extra revenue from tariffs would be used to cut taxes and this supposedly would help household incomes. But estimates of any extra revenue from tariffs are put at just $150bn a year. And income tax cuts will mainly benefit the higher income earners, while rising inflation will hit the lower income groups.

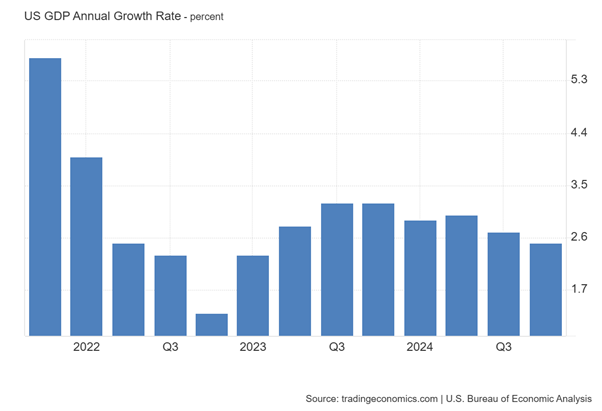

If the impact of the tariff increases were to reduce economic growth, then the so-called relative success of the US economy compared to other major economies would be in jeopardy. US real GDP growth has already slowed at the end of 2024 to a 2.3% annualised pace. The tariff measures would take that growth rate lower this year and next.

So as Trump imposes tariffs, US inflation is picking up and output growth is slowing down.

Those countries subject to Trump’s tariff increases will be hit hard. The Peterson Institute reckons that “for the duration of the second Trump administration, US GDP would be around $200 billion lower than it would have been without the tariffs. Canada would lose $100 billion off a much smaller economy, and at its peak, the tariff would reduce the size of the Mexican economy by 2 percent relative to its baseline forecast.” Indeed, JP Morgan economists reckon these measures could push both Canada (already weak) and Mexico into an outright recession.

The impact on China will depend of the size of the tariff increases. At the moment, it’s only 10% but Trump has said it will eventually be 60%. If the US imposed an additional 10 percent tariff on China and China responded in kind, US GDP would be $55 billion less over the four years of the second Trump administration, and $128 billion less in China. Inflation would increase 20 basis points in the US, and after an initial dip, 30 basis points in China.

These estimates assume that the tariff measures will be implemented. So far, Trump has postponed their implementation as he continues his ‘bargaining’ tactics with his trading ‘partners’. But remember, he also plans to raise tariffs for all EU imports – and that is still to come.

Overall, increased tariffs and other protectionist measures by all sides in retaliation will weaken world trade and economic growth. World trade growth showed some recovery in 2024 after contracting in 2023. Trump’s tariffs will stop that recovery in its tracks.

In the 1930s, the attempt of the US to ‘protect’ its industrial base with the Smoot-Hawley tariffs only led to a further contraction in output as part of the Great Depression that enveloped North America, Europe and Japan. Big business and their economists condemned the Smoot-Hawley measures and campaigned vociferously against them being implemented. Henry Ford tried to convince the then President Hoover to veto the measures calling them “an economic stupidity”. Similar words are now coming from the voice of big business and finance, the Wall Street journal, which called Trump’s tariffs “the dumbest trade war in history.”

The Great Depression of the 1930s was not caused by the protectionist trade war that the US provoked in 1930, but the tariffs then only added force to the global contraction, as it became ‘every country for itself’. Between the years 1929 and 1934, global trade fell by approximately 66% as countries worldwide implemented retaliatory trade measures.

While Trump has broken with the neo-liberal policies of ‘globalisation’ and free trade in order to ‘make America great again’ at the expense of the rest of the world, he has not dropped neo-liberal policies for the domestic economy. Taxes will be cut for big business and the rich, but also the aim will be to reduce the federal government debt and cut public spending (except for arms, of course). This year, the US budget deficit will be almost $2 trillion, of which more than half is net interest – about as much as America spends on its military. Total government debt oustanding now stands at $30.2 trillion or 99 per cent of GDP. America’s debt as a percentage of GDP will soon exceed the second World War peak. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2034, US governmental debt will exceed $50 trillion – 122.4 per cent of GDP. The US will be spending $1.7 trillion a year on interest alone.

Trump has let Elon Musk loose to massacre federal government spending, close down departments (possibly closing the Department of Education) and sack thousands of public employees to ‘reduce wastage’. The problem for Musk is that most of the ‘wastage’ and spending is on ‘defense’, but no doubt he will plough on reducing civilian services and even ‘entitlement programs’ like Medicare.

Trump aims to ‘privatise’ as much of government as he can. “We encourage you to find a job in the private sector as soon as you would like to do so,” the Trump administration’s Office of Personnel Management’s said. As Trump sees it, the public sector is unproductive, but not the finance sector, of course. “The way to greater American prosperity is encouraging people to move from lower productivity jobs in the public sector to higher productivity jobs in the private sector.” – these great jobs were not identified. Moreover, if the private sector stops growing as the trade war intensifies, those higher productivity jobs may not materialise anyway.

Trade tariffs as economic policy: the debate

Feb. 8 (The Next Recession) — Michael Pettis is an American professor of finance at Guanghua School of Management at Peking University in Beijing and a nonresident senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He has become a popular media source on China’s economy but also on global trade and investment trends.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s announcement of tariff hikes on US imports from a range of countries, Pettis has been expounding the view against the consensus in mainstream economics that tariffs can sometimes be beneficial to a country and even the world economy.

His argument centres on the view that: “[unlike in the 1930s], Americans consume far too large a share of what they produce, and so they must import the difference from abroad. In this case, tariffs (properly implemented) would have the opposite effect of [the] Smoot- Hawley [tariffs of the 1930s]. By taxing consumption to subsidize production, modern-day tariffs would redirect a portion of US demand toward increasing the total amount of goods and services produced at home. That would lead US GDP to rise, resulting in higher employment, higher wages, and less debt. American households would be able to consume more, even as consumption as a share of GDP declined.”

He goes on: “Thanks to its relatively open trade account and even more open capital account, the American economy more or less automatically absorbs excess production from trade partners who have implemented beggar-my-neighbor policies. It is the global consumer of last resort. The purpose of tariffs for the United States should be to cancel this role, so that American producers would no longer have to adjust their production according to the needs of foreign producers. For that reason, such tariffs should be simple, transparent, and widely applied (perhaps excluding trade partners that commit to balancing trade domestically). The aim would not be to protect specific manufacturing sectors or national champions, but to counter the United States’ pro-consumption and anti-production orientation.”

Pettis claimed that US tariffs, even though it is a tax on consumption, would not necessarily make American consumers worse off. “American households are not just consumers, as many economists would have you believe, but also producers. A subsidy to production should cause Americans to produce more, and the more they produce, the more they are able to consume.” For example, if the US were to put tariffs on electric vehicles, US manufacturers would be incentivised to increase domestic production of EVs by enough to raise the total American production of goods and services. If they did, then American workers would benefit in the form of rising productivity. In turn, this would lead to wages rising by more than the initial price impact the tariffs had and American consumers would be better off.

Pettis argued that “It was direct and indirect tariffs that in 10 years transformed China’s EV production from being well behind that of the US and the EU to becoming the largest and most efficient in the world”. So tariffs may not be an especially efficient way for industrial policy to force this rebalancing from consumption to production, but it has a long history of doing so, and “it is either very ignorant or very dishonest of economists not to recognize the ways in which they work…To oppose all tariffs on principle shows just how ideologically hysterical the discussion of trade is among mainstream economists.”

Pettis’ favourable view of Trump’s tariffs policy produced a broadside of attacks by mainstream neo-classical and Keynesian economists. Paul Krugman, the Keynesian guru who got a ‘Nobel’ prize for his contribution to international trade analysis, reckoned Pettis was just “mostly wrong”.

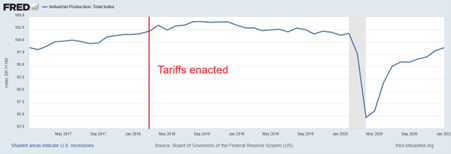

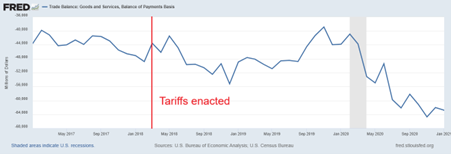

Keynesian economics blogger Noel Smith noted that Pettis reckoned that cheap Chinese imports actually made Americans poorer, by reducing their domestic production so much that Americans actually end up consuming less. Really, proclaimed Smith? “I’m highly skeptical of this argument, since a basic principle of economics is that people don’t voluntarily do things that make them poorer.” (Smith). Smith retorted that Trump’s tariffs in his first term did not boost domestic production as Pettis claimed tariffs could. Industrial production actually declined after Trump put up his tariffs:

Moreover, the trade deficit did not decline at all.

Pettis was failing to consider other factors, in particular, the dollar exchange rate with other trading currencies. The dollar appreciated in response to the tariffs, cancelling out at least part of the tariff effect on import prices. And it was not just households that had to pay more for imported goods in the shops, US manufacturers also suffered when they had to pay a lot more for parts and components.

Neoclassical economist Tyler Cowan also launched in, outlining “the mistakes of Michael Pettis”. “Michael Pettis does not understand basic international economics”. “He talks about tariffs (FT) as if they are anti-consumption, but pro-production. But tariffs are anti-production on the whole…. he basically presents an argument that we would expect economics undergraduate majors to reject.”

Certainly, the empirical evidence suggests that tariffs do not lead to a rise in economic growth. “Using an annual panel of macroeconomic data for 151 countries over 1963–2014, we find that tariff increases are associated with an economically and statistically sizeable and persistent decline in output growth. Thus, fears that the ongoing trade war may be costly for the world economy in terms of foregone output growth are justified.”

Pettis’ argument has two features. First, he reckons that import tariffs would lead to import substitution ie domestic American manufacturers would increase production and replace foreign imports and so employment and incomes would rise for all. Second, what is wrong with the world economy are the imbalances in trade and international payments. The US runs a huge trade deficit because exporting nations like China and Germany have flooded the home market with their goods. Tariffs can stop that by allowing US manufacturers to compete.

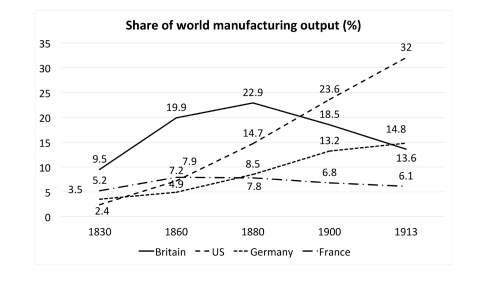

The first argument is really the old ‘infant industry’ argument, namely that countries just beginning to build their industrial base need to protect those ‘infant’ industries with tariffs from cheaper foreign imports. This was the economic basis for the tariff measures introduced by successive US administrations after the end of the civil war in the 1860s. This culminated in the Tariff Act of 1890, better known as the McKinley Tariff, which was a pivotal episode in US trade policy, dramatically raising import duties to near-record levels (by 38-50%).

Donald Trump referred to McKinley when announcing his executive orders to raise tariffs. “Under his leadership, the United States enjoyed rapid economic growth and prosperity, including an expansion of territorial gains for the Nation. President McKinley championed tariffs to protect U.S. manufacturing, boost domestic production, and drive U.S. industrialization and global reach to new heights.” Indeed, McKinley campaigned on raising tariffs so that internal taxes could be lowered, just as Trump campaigned in the 2024 election. “You go back and look at the 1890s, 1880s, McKinley, and you take a look at tariffs, that was when we were proportionately the richest,” Trump said.

In 1890 McKinley as a congressional rep proposed a range of tariffs to protest American industry. This was adopted by Congress. But the tariff measures did not work out well. They did not avoid a severe depression that began in 1893 and lasted until 1897. In 1896, McKinley became US President and presided over a new set of tariffs, the Dingley Tariff Act of 1897. As this was a boom period, McKinley claimed that the tariffs helped to boost the economy. Called the ‘Napoleon of Protection’, he linked his tariffs policy to the military takeover of Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Philippines to extend America’s ‘sphere of influence’ – shades of Trump But early in this second term as president from 1901, he was assassinated by an anarchist who had been enraged by the suffering of farm workers during the recession of 1893-7, which he blamed on McKinley.

Now we have another ‘Napoleon of Protection’ in Trump, who claims his tariffs will help American manufacturers in the same way that McKinley argued. But this time. the price will be paid by American households. Trump’s last set of tariffs in his first term raised domestic prices and hurt consumers much as the McKinley Tariff did in its time.

The debate here between Pettis and his critics boils down to two things. First, did the ‘infant industry’ argument hold at least for 19th century America, and if it did, can we apply it now for the US economy in the 21st century? The mainstream critics like Cowan are outright neoclassical supply and demand equilibrium theorists. Cowan reckons that over the long term, any change in supply and demand for American exports and imports caused by tariffs will lead to a price adjustment and a new balance. So there will be no gain for American industry.

Pettis correctly replied to Cowen’s fantasy world of equilibrium: “While I understand Cowen’s reliance on the “Econ 101” model, which assumes that prices always adjust to balance supply and demand, this framework isn’t relevant in the context of current global economic conditions. Prices have not adjusted in the US or many other countries over several decades.”

But Pettis fails to accept the obvious: that the US in the 21st century is not an emerging industrial power that needs to protect burgeoning new industries from powerful competitors. Instead, it is a mature economy with a declining industrial sector that will not be restored in any significant way by tariffs on Chinese or European imports.

As long ago as the 1880s, Friedrich Engels pointed out that when a capitalist economy is dominant worldwide, it is in favour of free trade and no tariffs, as Britain was in the mid-19th century and the US was in the 1950s to the 1980s. But the long depression of the 1880s and 1890s saw Britain’s manufacturing dominance decline and British policy switched to protectionist tariffs for its vast colonial empire.

Engels commented then: “if any country is now adapted to acquiring and holding a monopoly of manufacturing, it is America.” Engels reckoned that America’s tariffs from the 1860s had helped ‘nurture’ the development of large scale industry, but eventually as the US gained dominance, protective tariffs would “simply be a hindrance.” In the 21st century, America is Britain in the late 19th century; and China is the America of the 20th century – at least in industrial terms. Thus now Trump and Pettis want tariffs; while China wants free trade.

Pettis, in defending his argument for tariffs against his mainstream critics raised, what he called the “wider picture”, namely that China (and until recently Germany) exported for growth rather than consumed. As a result, workers wages were held down in China and Germany while the US became the final consumer for their exports and thus over consumed. This was the reason for trade imbalances that must be corrected by tariffs.

It is the thesis that Pettis and co-author Matthew Klein developed in their book Trade wars are class wars, a title that so enthused not only the mainstream media but attracted support from the left (indeed, I remember Klein being invited to participate in a left-wing online discussion on international trade and suddenly realising where he was, blurted out that he was ‘not a Marxist’. Of course, this was not his fault as the hosts should have known better!).

Klein-Pettis reckoned that the industrial policy of ‘investment for export’ by countries like China and Germany create ‘global imbalances’ that encouraged dangerous reactions like those from Trump. So Trump’s actions were the fault of China and Europe. You see, some economies (China) are ‘saving’ too much ie not investing at home enough to use up savings and instead export abroad, running up big trade surpluses. Others are forced to absorb these surpluses with excessive consumption (US) and so run large current account deficits. So we have trade wars as governments like Trump’s try to reverse this trend.

This is a bit like Trump’s argument that Mexico and Canada were causing a drugs overdose epidemic in the US by exporting fentanyl and it had nothing to do with Americans demanding cheap imported drugs to help their depressions.

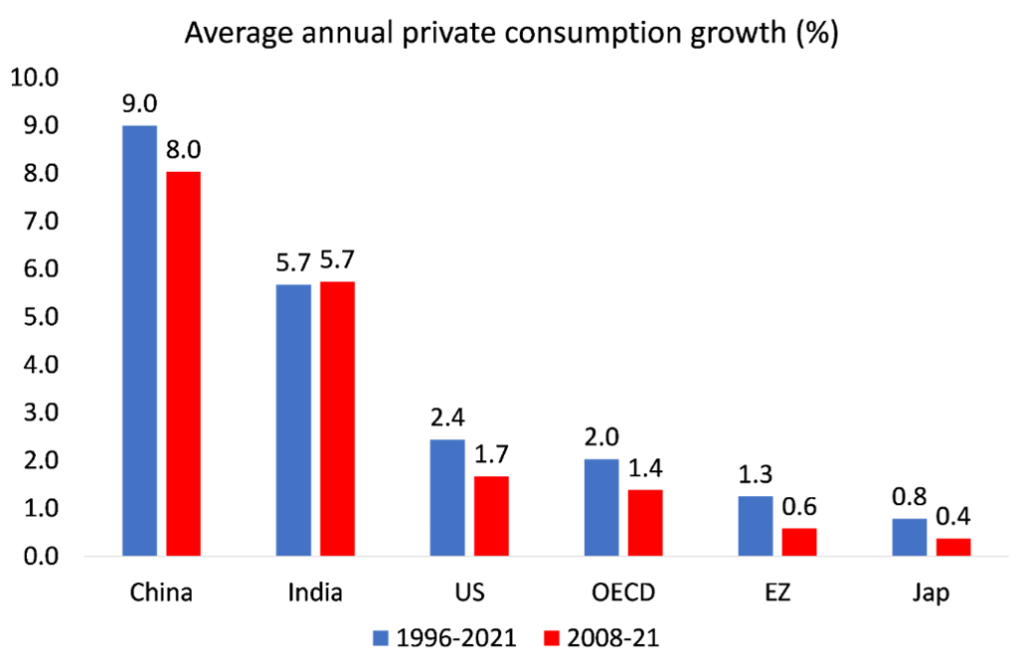

Klein and Pettis were saying that these trade imbalances are caused by the decisions of governments like China and Germany that seek to suppress wages and consumption (the class war), in order to boost investment and export surplus savings. Klein and Pettis reckoned that “The problem emerged when the Chinese economy could no longer absorb new investment productively. … Once China reached that point, consumption was too low to drive growth, and it entered into a state of excess production.”

But as I showed in my review of that book and in several other posts, this thesis is nonsense. It was just not true that household consumption in China is being repressed. Actually, personal consumption in China has been increasing much faster than fixed investment in recent years (even if it is starting at a lower base) and faster than in the US or any other G7 economy. Pettis and Klein’s own empirical analysis reveals that there has been a rise in consumption as a share of GDP in China in the last ten years, even without recognising that this is a probable underestimate of the size of household consumption in the stats (which exclude many public services or the ‘social wage’).

Any proper analysis of the trade imbalances would recognise that they are not the result of ‘excess savings’ or ‘weak domestic demand’ in China and ‘inadequate savings’ or ‘excessive demand’ in the US. This view is a false Keynesian analysis that ignores the supply-side forces of strong investment in technology reducing unit costs of production to gain a competitive advantage in international trade.

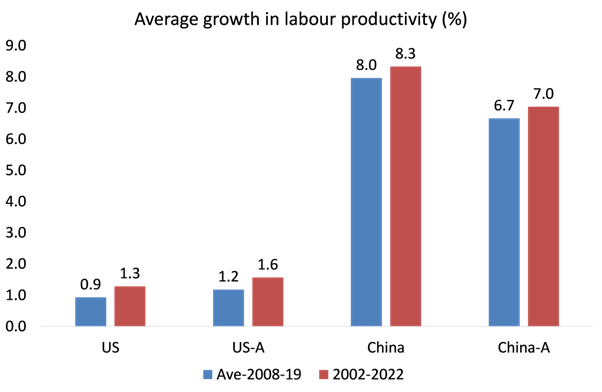

Germany and China were just outcompeting US industry through increasingly superior technology and productivity growth. Indeed, even on the adjusted (A) Western measures of labour productivity growth during the COVID period, China has done way better than the US.

Over the last 30 years, China’s savings rate rose 25.8%, but its investment rate rose more, 26.8%; so no ‘savings glut’ there, at least over the long term. Indeed, in the global boom period of 1990s, China’s investment rate rose much faster than its savings rate and there were no large surpluses on the current account. Only in the short period of 2002-7 did China run a large net savings surplus when the US has a credit-fuelled consumer boom before the global financial crash.

In their book, Klein and Pettis argued that: “The rest of the world’s unwillingness to spend — which in turn was attributable to the class wars in the major surplus economies and desire for self-insurance after the Asian crisis — was the underlying cause of both America’s debt bubble and America’s deindustrialisation.” But this is historically inaccurate. Since the 1970s, the US had been losing market share in manufacturing and trade and running current account deficits, not just after the Asian crisis. The cause of this decline was down to the relative weakness of US productivity growth, not Asian ‘excess savings’. Moreover, US manufacturing companies had shifted their production abroad during the 1980s.

Ironically, in trying to defend his pro-tariff policy from his orthodox critics, Pettis reversed the view in his book. He replied: “Contrary to Cowen’s claim, US business investment is not constrained by a lack of American savings. Just look at what US businesses say. They argue that if they are not investing in increased manufacturing, it is more likely because they do not believe they can produce profitably in the face of intense global competition, particularly from countries like China, Germany, South Korea and Taiwan, whose trade surpluses reflect a competitive advantage achieved at the expense of weak domestic demand. Another way to assess this is by looking at what businesses do with retained earnings. If US companies were eager to invest domestically but constrained by a lack of savings, they would not be sitting on massive cash reserves or spending heavily on share buybacks and dividend payments. This suggests that the problem is not a shortage of capital but a lack of profitable investment opportunities in the US.”

Apart from the reference to ‘weak domestic demand’, what Pettis says is right. American capital did not invest to sustain its manufacturing superiority because the profitability of that sector had fallen too mcuh. Instead, they switched to investing in financial assets and/or shifting their industrial power abroad. In the last couple of decades they hoped to sustain an advantage in hi-tech and information technology including AI. Now even that is under threat.

But this is not the fault of China running an ‘unfair’ industrial trade policy that is based on suppressing the living standards of its people; on the contrary, it is the failure of US capital to sustain its hegemony, just as Britain did in the late 19th century. Pettis attacks China’s success and calls for the US to protect its ailing industries with tariffs. If anything, that is likely to reduce the living standards of Americans instead.