In the following article, which was originally published by UK-China Film Collab, Asma Waheed looks at the abiding popularity of Indian cinema in China despite the ups and downs of the countries’ bilateral political relations over the decades.

Asma notes that while there has rightly been much attention paid to East-West cinematic exchange, “it is equally important to examine East-East cinematic exchange – in this case, the relationship between Indian and Chinese cinema… Bollywood’s popularity in China provides a real threat to Hollywood’s once-held monopoly in the global film market. But the story of Bollywood in China is not confined to the 21st century – instead it spans across to the 1950s, a time where both countries had undergone monumental change.”

The beginnings of Indian film success in China date from the 1951 film Awaara, or Liulangzhe (流浪者). Directed, produced and starring Raj Kapoor, a legendary icon in Indian film, the story follows the life of a young man, Raj, as he becomes entangled in a life of crime. A mainstay of the Golden Age of Indian cinema, in its exploration of themes such as destiny, justice, and morality, Awaara became a symbol of new nation-building in a post-independence India.

In an act of cultural exchange and diplomacy, the Indian People’s Theatre Association brought Awaara to China in 1955. Such was its popularity that even Chairman Mao was said to be a great fan of the film and its title song, Awaara Hoon. (The Indian People’s Theatre Association [IPTA] is the oldest association of theatre artists in India. It was formed in 1943 and promoted themes related to the Indian freedom struggle against British colonial rule. Communist leaders such as PC Joshi, General Secretary of the Communist Party of India [CPI], and Sajjad Zaheer, General Secretary of the Progressive Writers’ Association, were instrumental in its formation. It remains the cultural wing of the CPI.)

Today, a key inheritor of this legacy is Aamir Khan, famed for his 2001 anti-colonial cricketing epic Lagaan. Asma notes that:

“In the surveys and research regarding South Asian and East Asian film relationships, a primary reason for why audiences enjoyed Aamir Khan’s film and other Indian films was the shared cultural values. This may be surprising to some, but in Yanyan Hong’s research, it found that Indian film movie-goers were attracted to the film’s engagement with social issues relevant to both Indian and Chinese societies.”

She concludes: “The status of Indian cinema in China has shifted with the political climate, enjoying bouts of immense popularity before falling out of favour, only to reemerge years later. The nature of the film industry is such that it has become a vehicle for cultural diplomacy – whether Indian cinema will see another spike of interest in China remains undecided, but their relationship serves as a clear example of how good storytelling resonates across borders, adapting to the unique landscapes of each country and society. More importantly, it showcases the shared nature of human experiences across different cultures and highlights the similarity across seemingly different people.”

As the world grows more globalised in the 21st century, the impacts on the film industry are undeniable.

China emerged as one of the world’s largest box office markets, with over 90,000 cinema screens in the country, and Korean director Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite made history as the Oscars. Fuelled by diasporic communities mainly in the US and UK, Bollywood too continues to garner attraction across the globe. It is certain that the film industries of South and East Asian countries are driving their soft-power transnationally, evident in Korea’s Hallyu Wave growing from a regional trend in East Asia to now a tsunami sweeping across the globe.

There has rightly been much attention on the East-West cinematic exchange, and it is long overdue that Asian cinema has received praise in Hollywood institutions. However to better understand cinema in a global context, it is equally important to examine East-East cinematic exchange— in this case, the relationship between Indian and Chinese cinema.

In this essay series, I will explore the evolving and dynamic relationships between South Asian cinema and two markets— China and the UK. As a country with a considerable South Asian population, the UK presents an interesting case for understanding the reach of Bollywood beyond the subcontinent. Meanwhile, as two of the world’s most sizeable economics, India and China’s film industries offer a fascinating and important case study of cross-border cultural exchange in a globalised world.

In many people’s minds, Indian cinema— especially Bollywood[1]— is a genre full to rhetorical brim with melodramatic narrative, musical sequences, and grand dance numbers. But it is the unique and emotional storytelling that struck a chord with Chinese audiences, leading to major commercial success— indeed, Bollywood’s popularity in China provides a real threat to Hollywood’s once-held monopoly in the global film market.[2] But the story of Bollywood in China is not confined to the 21st century— instead it spans across to the 1950s, a time where both countries had undergone monumental change.

Awaara – Making Waves in China

For many Chinese cinephiles, both old and young, the 1951 Indian film Awaara , or Liulangzhe (流浪者), would serve as the beginning of Indian film success in China. Directed, produced and starring Raj Kapoor, a legendary icon in Indian film, the story follows the life of a young man, Raj, as he becomes entangled in a life of crime. A mainstay of the Golden Age of Indian cinema, in its exploration of themes such as destiny, justice, and morality, Awaara became a symbol of new nation-building in a post-independence India.

In an act of cultural exchange and diplomacy, the Indian People’s Theater Association brought Awaara across the border to China in 1955.[3] The film’s ideological synergy with China is evident in its rapid rise to popularity— it is even said that Mao was a great fan of the film and its title song, ‘Awaara Hoon’.[4] Beyond its socialist ethos, the film’s social commentary and debate of nature-vs-nurture resonated with Chinese audiences— despite supposed cultural and historical differences, its popularity highlights how Chinese viewers saw reflections of their own experiences of national transformation in the film’s narrative.

However, the film’s popularity followed the shifting political tides. During the Cultural Revolution, Awaara and its songs were denounced as “corrupting bourgeois weeds”, and it subsequently dropped out of the limelight after 1965. It was only after the social and economic reforms of 1979 that the film reemerged, recapturing immense favour. This time, however, its appeal was borne from shared cultural values— Chinese audiences related to the importance of family, parent-child relationships, and education that served as an undercurrent to the story. Moreover, the melodrama, song-dance sequences, and emotional sentimentality of Awaara— now typical features of Bollywood— took centre stage, ensuring its legendary status in classic Indian film.[5]

Awaara ostensibly may be the introduction of Indian cinema into China, but another film that deserves recognition is the 1971 Caravan, or Dapengche (大篷车). Directed by Nasir Hussain and produced by his brother, Tahir Hussain, Caravan was the first Indian film to be officially screened in China. It was a huge box-office success, and alongside Noorie (1979) and Disco Dancer (1982), these films dominated the foreign film market in 1980s China, and aided in establishing Indian film and Bollywood as an important tool of cultural exchange.[6]

This legacy now continues through Aamir Khan, the son of Caravan’s producer, Tahir Hussain. It was Raj Kapoor’s stardom that played a key role in elevating Indian cinema’s status in China during the late 20th century. Today, this idea of stardom as a powerful tool of cultural film diplomacy is even more apparent as we look at the magnitude of Aamir Khan’s growing popularity in China as it continues to bridge the two nations through the magic of cinema.[7]

Into the 21st century – Aamir Khan frenzy

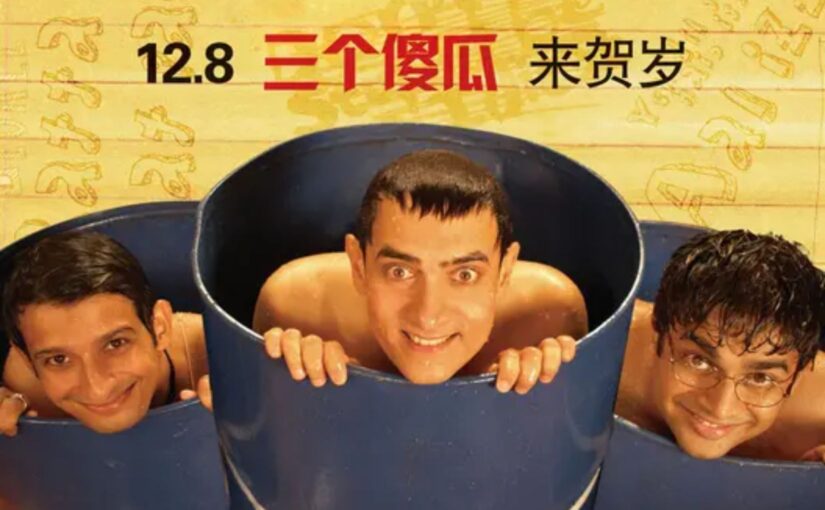

What began with the circulation of a pirated copy of 3 Idiots (2009) has blossomed into years of surging popularity for Aamir Khan. Willingly or not, he has become the face of modern Indian cinema in China. Within the catalogue of his many successful films, including Lagaan (2001), Taare Zameen Par (2007), PK (2014), and Secret Superstar (2017), the crown jewel is Dangal (2016), which racked up $193million at Chinese box office.[8] A biographical story about an ex-wrestler raising his daughters as wrestlers, the film is more than just a sports drama: emphasising the importance of education, parental guidance, self-belief, resilience, Dangal captivated the Chinese audience.

In the surveys and research regarding South Asian and East Asian film relationships, a primary reason for why audiences enjoyed Aamir Khan’s film and other Indian films was the shared cultural values. This may be surprising to some, but in Yanyan Hong’s research, it found that Indian film movie-goers were attracted to the film’s engagement with social issues relevant to both Indian and Chinese societies.[9] Similarly, a survey conducted by Muhammed Yaqoub saw Chinese cinephiles enjoyed Indian films due to their focus on the “emotional world of small people” and the “values and outlook on life [in Indian film] was closer to real life.”[10] Where the shared value system between India and China originates from is an entire academic field I wouldn’t do justice to by trying to summarise it here, but the director of Padman, R. Balki, said as the “emotions of Indians and Chinese are similar” it facilitates a deeper connection between the two audiences.[11]

Alongside these cultural parallels, Aamir Khan’s star power has been instrumental in boosting Indian cinema’s reputation in China. His marketability is evident in how online Chinese fans engage with his life— for example, many expressed great concern when he fell sick with COVID-19.[12] In the survey conducted by Yaqoub, over 80% of people named Aamir Khan as their favourite Indian actor/director.[13] His widespread popularity has been instrumental in expanding the influence of Indian cinema in China.

The success of these films are even more impressive when considering the challenges foreign films face in releasing in Chinese cinemas. As the Chinese film market has developed over the past few decades, the country operates under a strict quota system which favours domestic films. Under the “34 Foreign Films” policy, implemented in 1994, only 34 foreign films can be released in a year, and most have delayed releases in comparison to other countries.[14] The delayed release alongside the circulation of pirated copies were cited as reasons why Crazy Rich Asians (2018) failed to perform in Chinese box office, yet Dangal (2016) was also hit with a year-long delay and pirating issues but still managed to have 16-day box office streak.[15] In fact, 3 Idiots was also introduced to China through pirated copies with no exposure to marketing tricks, yet it became a box-office hit when released two years after its Indian premiere. Now, it’s ranked 9.2 out of 10 on Douban, and is 14th place on the platform’s list of greatest movies of all time.[16]

Since Aamir Khan’s re-popularisation of Indian cinema in China, there have been a few noticeable box office hits, such as Andhadhun (2018) which took in $47.57million in China alone, and a handful of noteworthy co-productions, such as Kung Fu Yoga (2017) and Xuan Zang (2016), following the China-India Co-Production Agreement of 2014.[17] While the COVID-19 pandemic, trade tensions of 2020 and border skirmishes have led to a decline in cross-border production collaboration, Indian cinema’s presence in China was revived by the release of Maharaja (2024), the first Indian film to be released in China after the two countries reached an agreement regarding a military stand-off in October 2024.[18] The movie was a commercial success, receiving an 8.7 out of 10 on Douban, and raking in around $10million in box office.[19]

To the Future

The status of Indian cinema in China has shifted with the political climate, enjoying bouts of immense popularity before falling out of favour, only to reemerge years later. The nature of the film industry is such that it has become a vehicle for cultural diplomacy— whether Indian cinema will see another spike of interest in China remains undecided, but their relationship serves as a clear example of how good storytelling resonates across borders, adapting to the unique landscapes of each country and society. More importantly, it showcases the shared nature of human experiences across different cultures and highlights the similarity across seemingly different people.

This relationship extends beyond China— Indian cinema also plays a vital role in moulding cultural exchange in the UK, where the large South Asian diaspora has long been a key audience for Bollywood’s global audience. Indian cinema serves as a cultural bridge— whether that be through its nostalgic element, or through its entertainment factor— for both members of the diaspora and non-members. With the UK’s relationship with Indian cinema being shaped by unique historical and social influences, it is worth exploring how the UK’s engagement with Bollywood differs from that of China, and what distinct creations in cinema and cultural exchanges have evolved as a result.

Bibliography

Chan, Hiu Man , and Faisal Ahmed. “South China Morning Post.” South China Morning Post, February 26, 2021. https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3123144/amid-china-india-tensions-bollywood-and-cinema-can-help-bridge.

Clini, Clelia, Rohit K Dasgupta, and Yanling Yang. South and East Asian Cinemas across Borders. Routledge, 2021.

Conner, Alison W. “Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens?” Law/Text/Culture 18, no. 1 (January 1, 2014). https://doi.org/10.14453/ltc.555.

Dasgupta, Debarshi. “An Indian Thriller Is Winning over Audiences in China; More Films in the Pipeline to Woo Them.” The Straits Times, December 14, 2024. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/an-indian-thriller-is-winning-over-audiences-in-china-more-films-in-the-pipeline-to-woo-them.

Govil, Nitin. “China, between Bombay Cinema and the World.” Screen 60, no. 2 (2019): 342–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjz018.

Hong, Yanyan. “The Power of Bollywood: A Study on Opportunities, Challenges, and Audiences’ Perceptions of Indian Cinema in China.” Global Media and China 6, no. 3 (June 14, 2021): 205943642110226. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364211022605.

Lee, Sangjoon. “Reorienting Asian Cinema in the Age of the Chinese Film Market: Introduction.” Screen 60, no. 2 (2019): 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjz010.

Liu, Zhongyin. “China Celebrates 10th Anniversary of Indian Movie ‘Three Idiots’ – Global Times.” Globaltimes.cn, 2019. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174909.shtml.

movie.douban.com. “豆瓣电影 Top 250,” (douban dianying) n.d. https://movie.douban.com/top250.

Muhammad Yaqoub, Zhang Jingwu, and Jonathan Matusitz. “The Chinese Love Affair with Indian Films: A Promising Future.” India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs 79, no. 3 (September 1, 2023): 370–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/09749284231183333.

Muhammad Yaqoub, Zhang Jingwu, and Wang Haizhou. “Exploring the Popularity and Acceptability of Indian and South Korean Films among Chinese Audiences: A Survey-Based Analysis.” SAGE Open 14, no. 4 (October 1, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241302580.

Rai, Swapnil. “From Raj Kapoor to Aamir Khan: Understanding Bollywood Stars as Cultural Diplomats.” Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI), January 20, 2025. https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/iit/swapnil-rai.

Song Wei. “Dangal Underlines Popularity of Indian Films in China – Opinion – Chinadaily.com.cn.” Chinadaily.com.cn, 2017. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2017-07/20/content_30186720.htm.

Van Fleit Hang, Krista. “‘The Law Has No Conscience’: The Cultural Construction of Justice and the Reception of Awara in China.” Asian Cinema 24, no. 2 (October 1, 2013): 141–59. https://doi.org/10.1386/ac.24.2.141_1.

Yau, Elaine. “SCMP.” South China Morning Post, December 11, 2018. https://www.scmp.com/culture/film-tv/article/2177193/why-indian-films-dangal-and-toilet-are-so-popular-china-similar.

Footnotes

[1] ‘Bollywood’ refers to the Hindi-language film industry, whereas ‘Indian cinema’ would include the industries of all languages in India

[2] Muhammad Yaqoub, Zhang Jingwu, and Jonathan Matusitz, “The Chinese Love Affair with Indian Films: A Promising Future,” India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs 79, no. 3 (September 1, 2023): 370–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/09749284231183333.

[3] Krista Van Fleit Hang, “‘The Law Has No Conscience’: The Cultural Construction of Justice and the Reception of Awara in China,” Asian Cinema 24, no. 2 (October 1, 2013): 141–59, https://doi.org/10.1386/ac.24.2.141_1.

[4] Alison W Conner, “Trials and Justice in Awaara: A Post-Colonial Movie on Post-Revolutionary Screens?,” Law/Text/Culture 18, no. 1 (January 1, 2014), https://doi.org/10.14453/ltc.555.

[5] Conner, “Trials and Justice in Awaara”

[6] Song Wei, “Dangal Underlines Popularity of Indian Films in China – Opinion – Chinadaily.com.cn,” Chinadaily.com.cn, 2017, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2017-07/20/content_30186720.htm.

[7] Nitin Govil, “China, between Bombay Cinema and the World,” Screen 60, no. 2 (2019): 342–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjz018.

[8] Elaine Yau, “Why Indian films like Dangal and Toilet are so popular in China: similar problems

” South China Morning Post, December 11, 2018, https://www.scmp.com/culture/film-tv/article/2177193/why-indian-films-dangal-and-toilet-are-so-popular-china-similar.

[9] Yanyan Hong, “The Power of Bollywood: A Study on Opportunities, Challenges, and Audiences’ Perceptions of Indian Cinema in China,” Global Media and China 6, no. 3 (June 14, 2021): 205943642110226, https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364211022605.

[10] Yaqoub, “The Chinese Love Affair”, 2023.

[11] Yau, “Why Indian films like Dangal and Toilet are so popular in China”, 2018.

[12] Swapnil Rai, “From Raj Kapoor to Aamir Khan: Understanding Bollywood Stars as Cultural Diplomats,” Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI), January 20, 2025, https://casi.sas.upenn.edu/iit/swapnil-rai.

[13] Yaqoub, “The Chinese Love Affair”, 2023.

[14] Muhammad Yaqoub, Zhang Jingwu, and Wang Haizhou, “Exploring the Popularity and Acceptability of Indian and South Korean Films among Chinese Audiences: A Survey-Based Analysis,” SAGE Open 14, no. 4 (October 1, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241302580.

[15] Zhongyin Liu, “China Celebrates 10th Anniversary of Indian Movie ‘Three Idiots’ – Global Times,” Globaltimes.cn, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1174909.shtml.

[16] “豆瓣电影 Top 250,” (douban dianying) movie.douban.com, n.d., https://movie.douban.com/top250.

[17] Sangjoon Lee, “Reorienting Asian Cinema in the Age of the Chinese Film Market: Introduction,” Screen 60, no. 2 (2019): 298–302, https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjz010.

[18] Debarshi Dasgupta, “An Indian Thriller Is Winning over Audiences in China; More Films in the Pipeline to Woo Them,” The Straits Times, December 14, 2024, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/south-asia/an-indian-thriller-is-winning-over-audiences-in-china-more-films-in-the-pipeline-to-woo-them.

[19] Dasgupta, “An Indian Thriller”, 2024.