US president-elect Donald Trump has been touting tariffs as a means to reduce both income taxes and the national debt, which currently exceeds 120 percent of GDP. In the article below, Ben Norton describes these claims as “utterly false, and mathematically absurd”.

Ben notes that, during Trump’s first term, significant tax cuts were enacted, primarily benefiting the wealthiest Americans. These cuts resulted in the richest billionaire families paying a lower effective tax rate than the bottom half of US households. Consequently, federal deficits increased from 3.4 percent of GDP in 2017 to 4.6 percent in 2019, prior to the pandemic-induced surge to 14.7 percent in 2020.

The article observes that “every advanced economy got its start through protectionism”, but that the US from the 1940s has been preaching (and sometimes violently imposing) free trade as a means of opening up markets for its exports. “However, something happened in the 21st century that changed everything: the People’s Republic of China carried out the most remarkable campaign of economic development in history.”

China’s extraordinary rise has taken place in parallel with a sharp decline in US manufacturing and an increasing financialisation of the US economy. “The US capitalist class decided it would much rather be the banker of the world rather than the factory of the world, because creating parasitic financial and tech oligopolies that use monopolistic market control and intellectual property to extract rents is much more profitable than actually making things.”

Trump’s proposed tariffs will not help the US to re-industrialise – such a project would require massive long-term investment in infrastructure, education, and research and development. In reality, tariffs will be used “to justify cutting taxes even further on the rich” and, further, “to escalate the new cold war on China, which is a bipartisan gift to the Military-Industrial Complex that will only distract from the domestic problems caused by the US ruling class and externalise the blame”.

This article originally appeared on Geopolitical Economy.

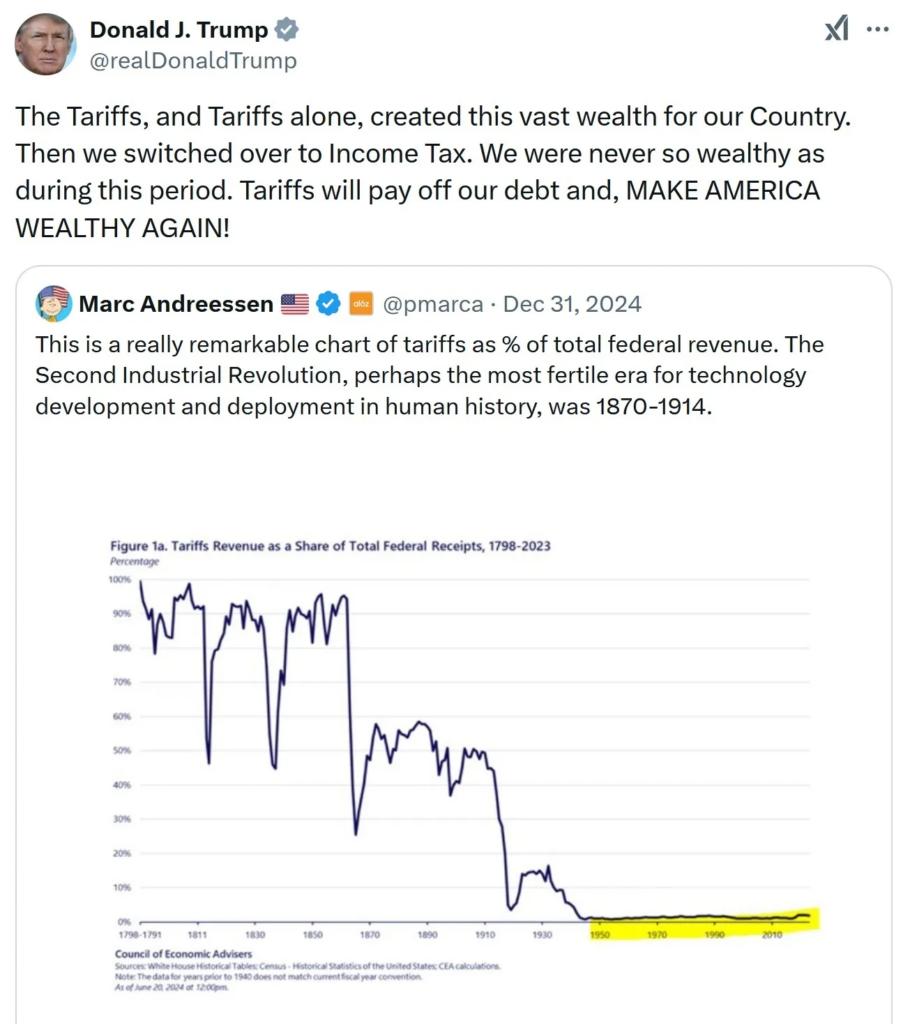

Donald Trump cited billionaire egghead venture capitalist Marc Andreessen to advocate for high tariffs. Trump argued that tariffs will magically replace the income tax and pay off US public debt (which is more than 120% of GDP). This is utterly false, and mathematically absurd.

For Trump, tariffs are just another convenient excuse to cut taxes on the rich — which will in fact increase the US deficit, and therefore public debt.

Thanks to Trump’s tax cuts during his first term, the richest billionaire families in the US paid a lower effective tax rate than the bottom half of households in the country. Meanwhile, US federal deficits increased from 3.4% of GDP in 2017 to 4.6% of GDP in 2019 (before the deficit blew out to 14.7% of GDP in 2020, due to the necessary stimulus measures during the pandemic).

As Trump continues to reduce taxes on fellow oligarchs, tariffs will decidedly not make up for the lost revenue. A study by the Wharton School, the elite business school of the University of Pennsylvania, estimated that Trump’s economic policies will increase the US deficit by $5.8 trillion over the next decade.

Nevertheless, the sudden interest in tariffs shown by US billionaires is about much more than just taxes; what it is really about is industrial hegemony and economic dominance.

Here is the actual history, which oligarchs like Trump and Andreessen don’t know:

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States used tariffs as a form of infant industry protection, to build up its domestic manufacturing capabilities, following the dirigiste ideas of Alexander Hamilton.

Every advanced economy got its start through protectionism (including Great Britain, France, Japan, South Korea, etc.). The state needed to protect infant industries during the initial industrial “catch-up” period, because it is very difficult for a developing economy to compete with a dominant economic power that already has an established industrial base that benefits from economies of scale.

By the 1940s, the US became the dominant industrial power on Earth, especially after World War Two destroyed its competitors in Europe. In 1946, US net exports were 3.2% of GDP; then, in 1947, they were 4.3% of GDP. This was a peak the US would never see again. (US net exports have been negative without exception since 1976, as the US has run the largest consistent current account deficits ever seen in history, which have only been possible to balance due to the fact that the US prints the global reserve currency, and can thus sell more and more Treasury securities and other financial assets to foreign holders of dollars.)

In the 1940s, US industry no longer had significant competition, so Washington lifted tariffs and began to preach “free trade”. This benefited the US, because at that time it had a large surplus, and insufficient domestic demand, so by imposing “free trade” (often forcibly), it could open new markets for its exports.

The US wasn’t concerned about losing local market share to a foreign manufacturer, because there weren’t any left at the top of the value chain. So US companies could dominate both foreign and domestic markets.

What the United States did was not unique; the British empire did the exact same thing in the mid 19th century. After the UK established industrial dominance, it repealed the Corn Laws in 1846, moved away from strict protectionism, and began to impose “free trade” on its colonies. (This history was detailed by economist Ha-Joon Chang in his groundbreaking book Kicking Away the Ladder.)

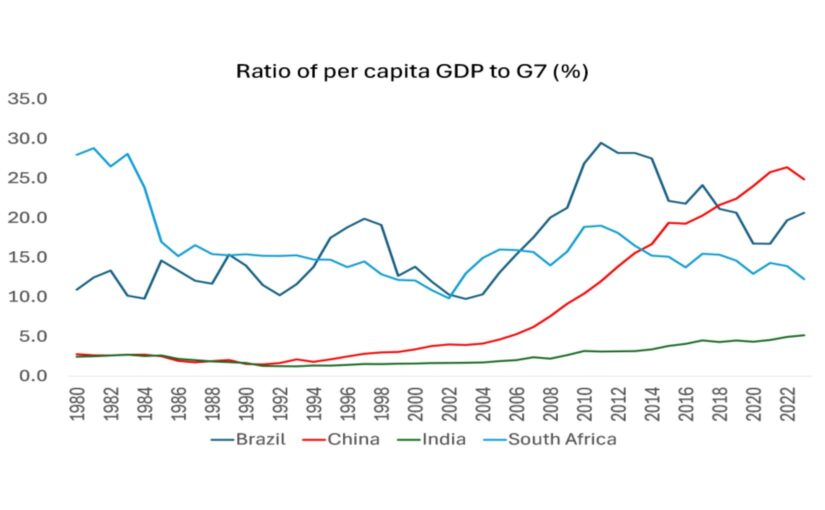

However, something happened in the 21st century that changed everything: the People’s Republic of China carried out the most remarkable campaign of economic development in history.

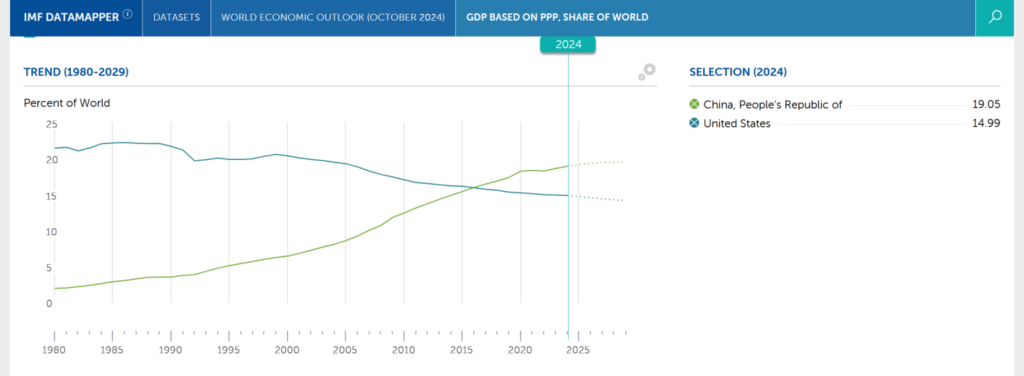

By 2016, China overtook the United States as the largest economy on Earth (when GDP is measured at purchasing power parity, according to IMF data).

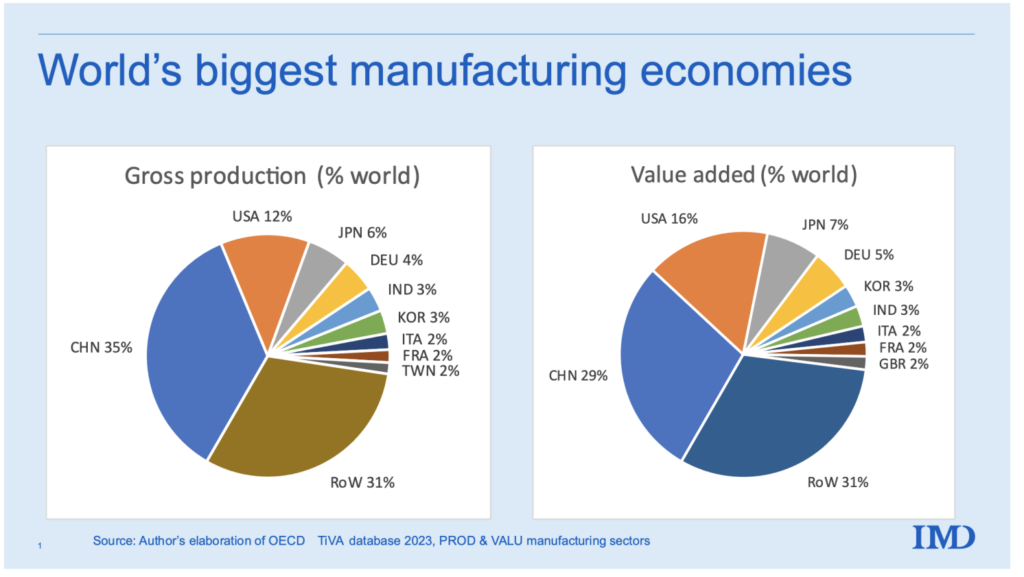

Even more importantly, China rapidly industrialized and established itself as

the “world’s sole manufacturing superpower”, responsible for 35% of global gross production.

Meanwhile, the US lost its industrial hegemony, due to the deindustrialization and financialization of its economy in the neoliberal era. The US capitalist class decided it would much rather be the banker of the world rather than the factory of the world, because creating parasitic financial and tech oligopolies that use monopolistic market control and intellectual property to extract rents is much more profitable than actually making things.

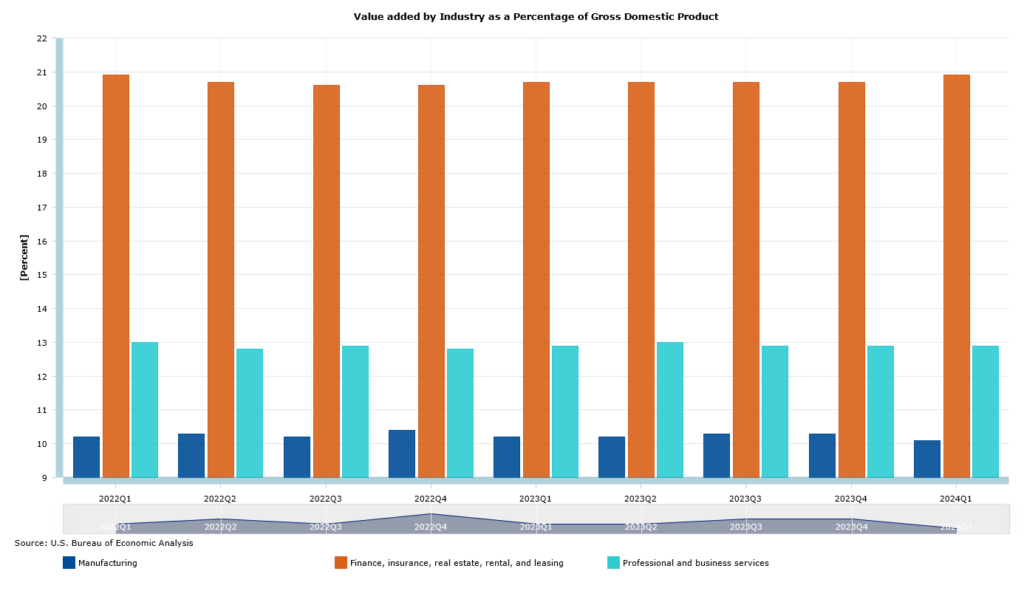

Just 10% of US GDP consists of manufacturing. More than double, 21%, is made up by the FIRE sector: finance, insurance, and real estate.

Today, US companies can no longer compete with Chinese firms. So what is the response of the US government, which is the representative of US monopoly capital? It has abandoned the “free trade” ideology it had spent decades imposing on the world, and has instead returned to its old strident protectionism.

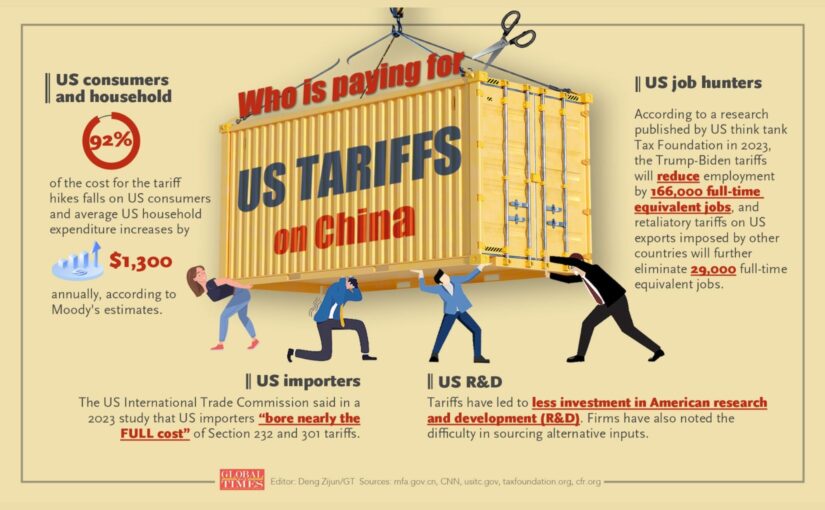

During his first administration, Trump launched a trade war on China. But this is totally bipartisan (as is the case with almost all US wars). Joe Biden has continued Trump’s trade and tech war on China, imposing even more tariffs.

Demagogues such as Trump like to scapegoat China for the problems that were caused by US oligarchs like him and Andreessen, who got much, much, much richer thanks to the deindustrialization and correspondent financialization of the US economy.

Now they think tariffs are the panacea that will fix everything. But they won’t, because the US industrial base has seriously eroded, and that can’t be rebuilt quickly; it takes many years.

Even more importantly, billionaire oligarchs on Wall Street — who are close friends and allies of Trump, Andreessen, Vivek Ramaswamy, and Elon Musk — will fight tooth and nail against a significant devaluation of the dollar, which would be needed to re-industrialize, reduce production costs, and disincentive imports. Financial speculators want a strong dollar, to keep inflating the biggest bubble in the history of US capital markets.

So the logical result of this is that Trump will use tariffs not truly to re-industrialize, but rather for two main reasons: one, to justify cutting taxes even further on the rich (thereby increasing US public debt, which will be pointed to to demand neoliberal austerity and slashes to social spending); and two, to escalate the new cold war on China, which is a bipartisan gift to the Military-Industrial Complex that will only distract from the domestic problems caused by the US ruling class and externalize the blame.