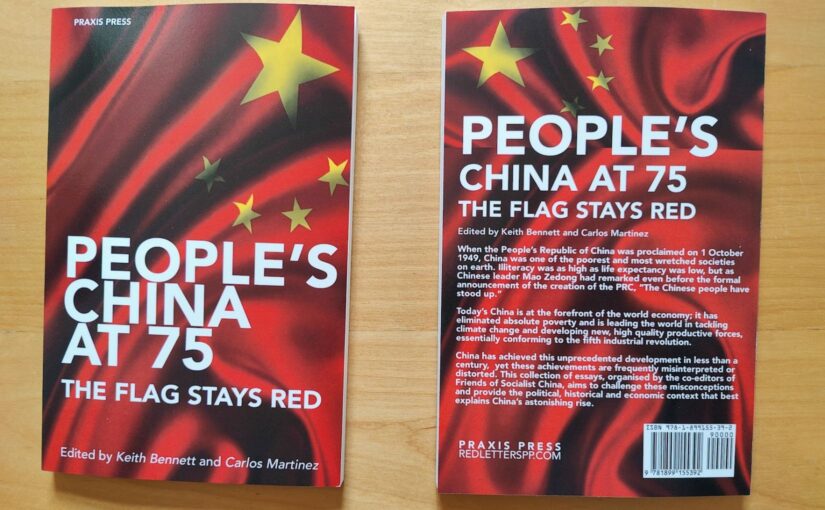

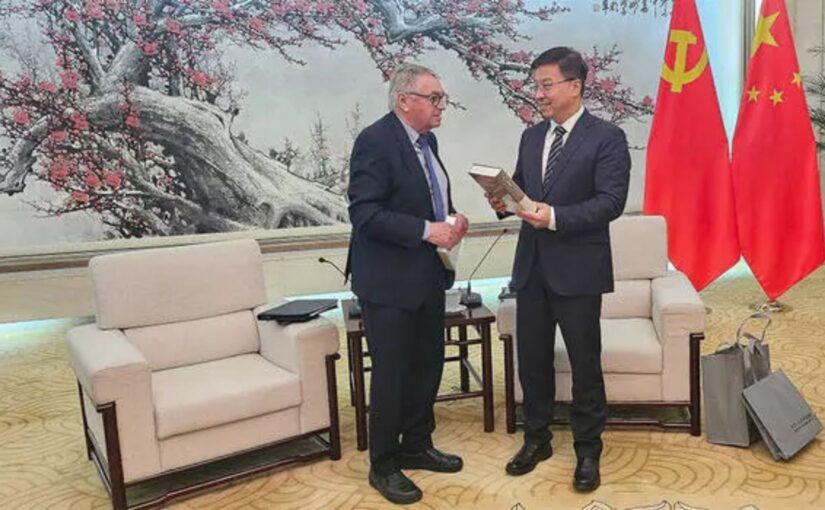

We are very pleased to republish below a comprehensive review by Gabriel Rockhill of “People’s China at 75: The Flag Stays Red”, edited by Keith Bennett and Carlos Martinez, the co-editors of this website, and published by Praxis Press.

Recalling how Lenin rejoiced when the October Revolution outlasted the Paris Commune, Gabriel notes: “Karl Marx, writing on these events at the time, celebrated the unprecedented advances of the workers’ movement while lucidly identifying its principal limitation: it had not crushed the bourgeois state and founded a proletarian state capable of defending its interests. This is a lesson that Vladimir Lenin had taken to heart, and his reputed dance in the snow feted the practical success of a correct theoretical assessment.”

On October 1st, 2024, for which anniversary this book was published, the People’s Republic of China eclipsed the longevity of the Soviet state.

How should those “who support the struggle for a more egalitarian and ecologically sustainable world” respond?

Gabriel notes that the book “seeks to respond to these questions and others through rigorous materialist analysis and a coherent theoretical framing of the PRC’s place in world history. Comprised of eleven incisive analyses framed by a capacious introduction, the book serves as a useful guide to anyone interested in a crash course on China by some of the world’s leading experts on the question. Given its readability, with concise essays and a total length of just under 150 pages, it is particularly well suited for full-time organisers and a broad readership outside of academic circles. Since it covers so much terrain and tackles many pressing questions head-on, it is, in many ways, a perfect primer on China. At the same time, it is packed with empirical details, extensive references, and insightful analyses that will be of interest to those with a strong working knowledge of the PRC.”

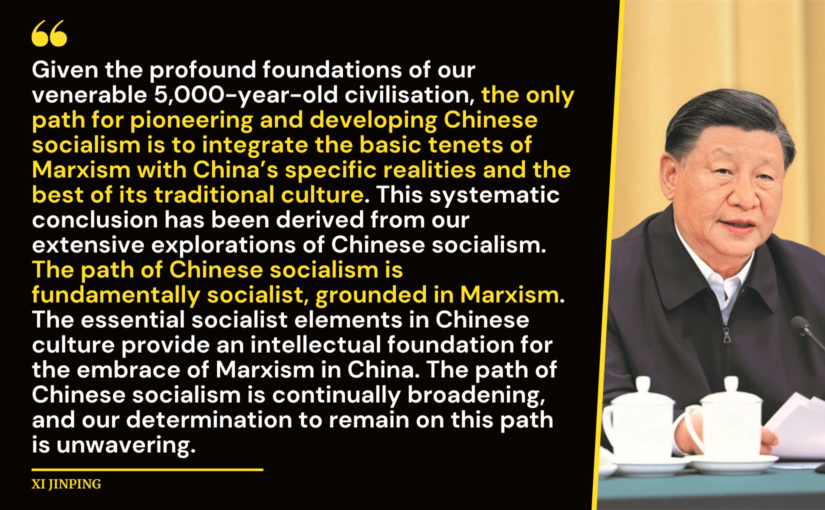

He goes on to argue that every socialist project has had to chart new territory in its own unique circumstances and explore ways of eking out an existence in a hostile, imperialist world intent on destroying it. Implicit in the book’s argument is the rejection of the idealist approach to the question of socialism, which consists in defining it in the abstract and then dismissing anything in the real world that does not live up to this speculative abstraction. Instead, Bennett and Martinez invite us to approach the issue of socialism from a dialectical materialist vantage point. This means recognising that it is a process that takes on specific forms in different material circumstances, and we, therefore need to analyse the complexities of practical reality rather than simply relying on theoretical definitions from the sidelines of history.

Outlining some of China’s achievements, as presented in the book, he writes that:

“Since many of these facts are undeniable and even admitted by the imperialist powers, there has been an attempt to attribute China’s meteoric rise to its supposed embrace of capitalism in the post-Mao era. Many analysts, including self-proclaimed Marxists, embrace a schematic and reductivist version of history that simply juxtaposes a socialist age under Mao to a capitalist epoch begun with Deng Xiaoping. One of the many strengths of this book is its dialectical and materialist approach to the history of the People’s Republic, which provides a fine-grained elucidation of the concrete realities of the PRC’s developmental strategy rather than falling prey to metaphysical ‘all or nothing’ assumptions.”

Echoing the conclusion of Deng Xiaoping’s November 1989 talk with Julius Nyerere, the founding president of Tanzania, Gabriel summates:

“As long as China remains on the socialist path, approximately one sixth of the world’s population will be living under socialism and striving – against great odds – to chart uncharted territory. As one of the longest lasting and largest socialist experiments on planet Earth, there is much to learn from it. This book is an indispensable guide to understanding the PRC and appreciating its impressive accomplishments in only seventy-five years of existence.”

Gabriel Rockhill is the Founding Director of the Critical Theory Workshop / Atelier de Théorie Critique and Professor of Philosophy at Villanova University, USA.

“People’s China at 75: The Flag Stays Red” can be purchased from the publishers in paperback and digital formats.

This review was originally published by Black Agenda Report. It has also been republished by Popular Resistance and Internationalist 360°. An abbreviated version was published by the Morning Star.

One of the most legendary scenes of revolutionary joy in the history of the world socialist movement is said to have occurred when Vladimir Lenin reportedly went out to dance in the snow in order to celebrate the fact that the recently minted Soviet Republic had outlasted the Paris Commune. The workers who had taken over the French capital in 1871 and launched a collective project of self-governance were able to hold out for seventy-two days before the ruling class trounced this experiment in a more egalitarian world. Karl Marx, writing on these events at the time, celebrated the unprecedented advances of the workers’ movement while lucidly identifying its principal limitation: it had not crushed the bourgeois state and founded a proletarian state capable of defending its interests. This is a lesson that Vladimir Lenin had taken to heart, and his reputed dance in the snow feted the practical success of a correct theoretical assessment.

The Soviet Union lasted for seventy-four years if one includes the five years of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1917-1922). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) recently outstripped it by celebrating its seventy-fifth birthday (1949-2024). Measured in years rather than days, the celebration organized in the Great Hall of the People was much more sober than Lenin’s purported frolic in the snow. It included a balanced appraisal of what has been accomplished thus far and what remains to be done. President Xi Jinping delivered a speech that stressed how the Communist Party of China (CPC) “has united and led the Chinese people of all ethnic groups in working tirelessly to bring about the two miracles of rapid economic growth and enduring social stability.”[1] Reactions in the imperial core, known for its histrionics regarding China’s imminent collapse, were markedly different. The title of one of the Associated Press’s articles directly contradicted Xi Jinping’s claim: “China marks 75 years of Communist Party rule as economic challenges and security threats linger.”[2]

Continue reading A major milestone in socialist history – a review of People’s China at 75: The Flag Stays Red