In this thought-provoking, sympathetic, but not uncritical article, Andrew Murray addresses himself to the question of the significance of the Chinese revolution, which, he notes in opening, is “the most important single fact of 21st-century politics.” Andrew demonstrates this by noting that the rise of China is bringing to an end centuries of European/North American hegemony at a global level; is reversing the economic ‘great divergence’ that began with the opium wars of the mid-19th century; and is challenging the monopoly of global violence at the state level exercised by the United States and its allies. As a result, “unipolarity now faces a systemic negation,” with many countries of the Global South now having socio-economic options they did not previously, thereby creating the possibility of a more equal world.

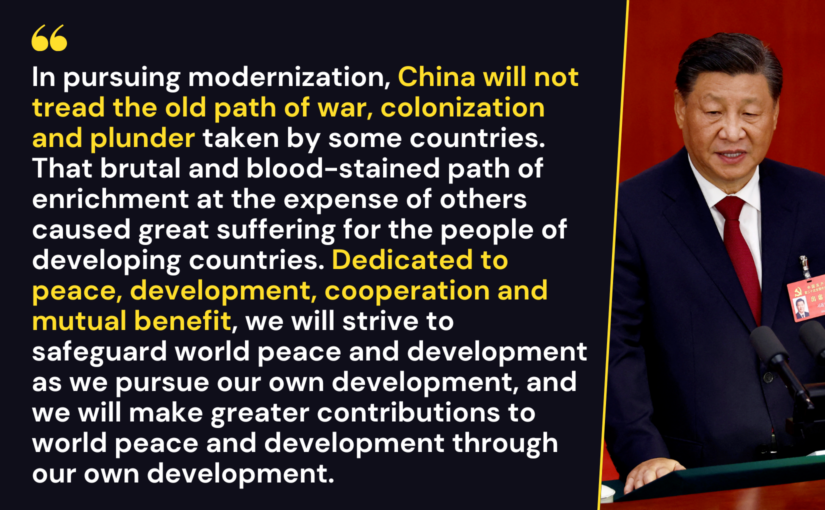

Andrew points out that whilst the concepts of socialism and capitalism have universal application, they are not invariant. “It would be wrong to expect a civilisation as old and developed as the Chinese not to modify our understanding of these unfinishable categories.” He notes that in the 20th century, two tendencies struggled for hegemony in the global socialist movement – the Soviet model, which ultimately collapsed, and social democracy, which in reality was not socialism at all and which can be seen as a product of imperialism. Drawing on Marx’s concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the understanding of socialism as a transitional form, he notes that, despite certain claims to the contrary, “no society has developed much beyond the foundations of socialism … the relatively modest claims made by the Communist Party of China … may be much better founded than the more sweeping claims … [and] the suppression of capitalism by socialism will be the work of a very long time, with numerous zigzags and experiments on the way.”

Regarding the concept of the ‘sinification of Marxism’, Andrew asserts that certain concepts of Mao Zedong and his comrades, such as placing the peasantry as a central revolutionary subject, the idea of surrounding the cities from the countryside, and the theory of new democracy, are of enduring importance. “China takes Marxism from the European labour movement and returns it to the world enriched, developed and nearer to universalism, but not, of course, ‘finished’.”

Turning to the changes initiated in China from the late 1970s, and the differences in line between Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, Andrew is of the view that “the former prioritised the transformation of social relations, while the latter prioritised the development of the forces of production. Either can be justified in Marxist terms.” In the author’s assessment, whereas Mao “fetishised” class struggle, his successors, such as Deng and Jiang Zemin, “radically diminished” its importance, “even as class differences have re-emerged quite sharply.” This, however, “did not make the People’s Republic a bourgeois society.”

Bringing the story up to the present, Andrew outlines Xi Jinping’s concept of six phases in the history of socialism, adding that what in China are referred to as the ‘four cardinal principles’, and which were originally advanced by Deng Xiaoping, “underline that there is no absolute rupture between CPC strategy today and that in Mao’s time. Mao himself was a flexible and sometimes contradictory thinker whose works can provide fertile justification for varying strategies.”

Without shying away from complexities, contradictions and caveats, moving towards his conclusion, Andrew notes that, “what is undeniable is that the future of socialism in the world depends very heavily on developments in China and on the leadership of its communist party. As Xi has said, without China socialism risked being pushed entirely to the margins of world affairs after 1991.”

In the view of the editors of this website, Andrew’s article is an important contribution to a vital debate that needs to be read and discussed seriously and widely. The author was previously the Chief of Staff at Unite, Britain’s second-largest trade union, Adviser to Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, and Chair of the Stop the War Coalition. He worked at the Morning Star daily newspaper, 1977-1985, and currently does so again. He is the author of a number of books, including most recently, ‘Is Socialism Possible in Britain?’, published by Verso.

The main themes of this article were first outlined by Andrew in his talk to the Friends of Socialist China meeting on the evolving significance of the Chinese revolution, where he exchanged views with visiting US professor Ken Hammond, at the Marx Memorial Library on 28 November 2022. This article was published in the 2023 edition of Theory and Struggle, journal of the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School, published by Liverpool University Press, who hold copyright. This accepted author manuscript is published under a Creative Commons Attribution License and with the kind permission of the author.

The broad significance of China’s rise is evident.1 It is the most important single fact of 21st-century politics and can be simply stated as follows.

First, it is bringing to an end two centuries of European/North American hegemony at a global level.

Second, it is reversing what has been called the ‘great divergence’ in economic power and prosperity, which began with the 19th-century opium war and opened up an enormous gap in favour of the west.

Third, it challenges the monopoly of global violence at the state level exercised by the United States and its allies.

In all these respects, China is bringing to an end the ‘unipolar moment’ that prevailed in world affairs after the end of the Soviet Union more than 30 years ago. Already weakened by US military defeats and the disastrous consequences of ‘Washington consensus’ economics, unipolarity now faces a systemic negation. At the global level, this means many countries of Africa, Asia and South America now have socio-economic options that they did not have previously. They have more room to shape their own futures. All this creates the possibility of a more equal world, with a lessening of the gross disparities that have been a central feature of the imperialist era.

In purely Chinese terms, the country’s development has led to a vast increase in prosperity for the Chinese people. Yet at the same time what was, under Mao Zedong, one of the most equal countries in the world has now become marked by dizzying inequality. Once rock-solid, if very basic, social security was comprehensively undermined and has only recently been reconstructed to some extent (it should be noted, however, that life expectancy has continued to rise throughout this period).

This has long raised the question among the left: what is the China that has done all this? A socialist state, or a capitalist one? What frames its development?

These are bigger questions than can be answered in a single article, particularly one by an author who claims no great expertise on China. Here I just want to advance some considerations for further reflection.

Continue reading Andrew Murray: The significance of the Chinese revolution