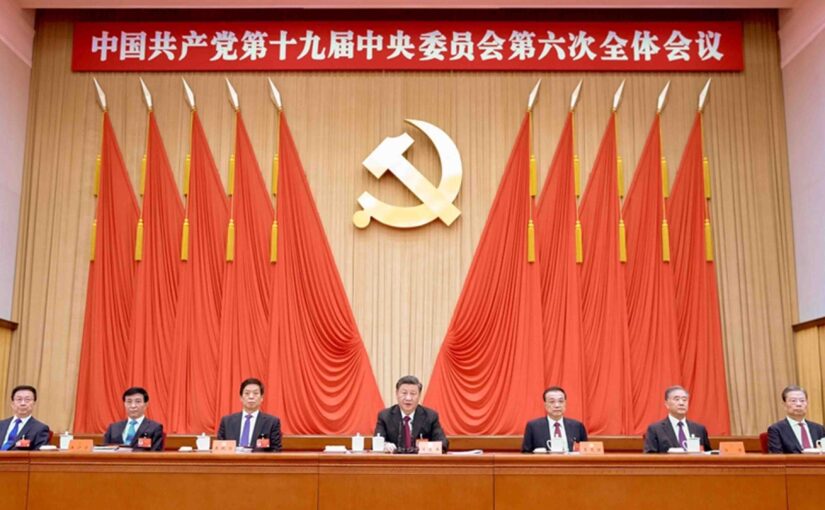

We are very pleased to publish here the full text of the Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century, which was adopted at the Sixth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on 11 November 2021.

It is a very long document but it needs to be carefully read by anyone with a serious interest in socialism in China, in Marxism and indeed, considering the vital and increasing importance of China in the world, in the future prospects of humanity.

In the last 100 years, this is only the third such resolution adopted by the CPC. The first, adopted in 1945, affirmed the correctness of Mao Zedong’s strategic line for the victory of the Chinese revolution and clearly established Mao Zedong Thought, along with Marxism-Leninism, as the guiding ideology of the CPC.

The second, adopted in 1981, while affirming Chairman Mao as a great proletarian revolutionary, sharply criticised the mistaken policies that led to the Cultural Revolution; formulated the theory of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics; and stressed the centrality of Reform and Opening Up to the building of China into a moderately prosperous nation.

The present resolution builds on these two historic documents to outline the contributions made by Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and especially Xi Jinping to the further consolidation of socialist positions in China. It further elucidates China’s place and role in the world and the vital importance of Marxism, to which Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era is both an application to the concrete conditions of China and a development in the 21st Century.

The resolution is justly proud of the achievements of the Chinese party and people, which are among the greatest, if not the greatest, in human history. Yet, contrary to the usual facile coverage in the Western media, it is far from a self-congratulatory collection of platitudes. It is sober, modest, concrete and, where appropriate, self-critical. As such it is a model of a Marxist, historical materialist document.

Friends of Socialist China intends to publish further material on this important and historic resolution.

Preamble

Since its founding in 1921, the Communist Party of China (CPC) has remained true to its original aspiration and mission of seeking happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation. Staying committed to communist ideals and socialist convictions, it has united and led Chinese people of all ethnic groups in working tirelessly to achieve national independence and liberation, and then to make our country prosperous and strong and pursue a better life. The past century has been a glorious journey.

Over the past hundred years, the Party has led the people to a number of important milestones: achieving great success in the new-democratic revolution through bloody battles and unyielding struggles; achieving great success in socialist revolution and construction through a spirit of self-reliance and a desire to build a stronger China; achieving great success in reform, opening up, and socialist modernization by freeing minds and forging ahead; and achieving great success for socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era through a spirit of self-confidence, self-reliance, and innovating on the basis of what has worked in the past. The endeavors of the Party and the people over the past century represent the most magnificent chapter in the millennia-long history of the Chinese nation.

A review of the Party’s major achievements and historical experience over the past century is necessary for the following purposes:

–starting a new journey to build China into a modern socialist country in all respects in the historical context of the Party’s centenary;

–upholding and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era;

–strengthening our consciousness of the need to maintain political integrity, think in big-picture terms, follow the leadership core, and keep in alignment with the central Party leadership;

–enhancing our confidence in the path, theory, system, and culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics;

–resolutely upholding Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Party Central Committee and in the Party as a whole and upholding the Central Committee’s authority and its centralized, unified leadership to ensure that all Party members act in unison;

–advancing the Party’s self-reform, building all Party members’ fighting capacity, strengthening their ability to respond to risks and challenges, and maintaining the Party’s vigor and vitality; and

–uniting and leading all Chinese people in making continued efforts to realize the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation.

All Party members should uphold historical materialism and adopt a rational outlook on the Party’s history. Looking back on the Party’s endeavors over the past century, we can see why we were successful in the past and how we can continue to succeed in the future. This will ensure that we act with greater resolve and a stronger sense of purpose in staying true to our Party’s founding mission, and that we more effectively uphold and develop socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era.

The Party adopted the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party at the seventh plenary session of its Sixth Central Committee in 1945 and the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China at the sixth plenary session of its 11th Central Committee in 1981.

These two resolutions embody a facts-based review of major events in the Party’s history, as well as important experience gained and lessons learned. These documents unified the whole Party in thinking and action at key historical junctures and played a vital guiding role in advancing the cause of the Party and the people. Their basic points and conclusions remain valid to this day.

I. A Great Victory in the New-Democratic Revolution

In the period of the new-democratic revolution, the main tasks of the Party were to oppose imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat-capitalism, seek national independence and the people’s liberation, and create the fundamental social conditions necessary for realizing national rejuvenation.

With a history stretching back more than 5,000 years, the Chinese nation is a great and ancient nation that has fostered a splendid civilization and made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. After the Opium War of 1840, however, China was gradually reduced to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society due to the aggression of Western powers and the corruption of feudal rulers. The country endured intense humiliation, the people were subjected to untold misery, and the Chinese civilization was plunged into darkness. The Chinese nation suffered greater ravages than ever before.

To save the nation from peril, the Chinese people rose to fight back, and patriots of high ideals sought to pull the nation together, putting up a heroic and moving struggle. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, the Westernization Movement, the Reform Movement of 1898, and the Yihetuan Movement rose one after the other, and a variety of plans were devised to ensure national survival, but all of these ended in failure. The Revolution of 1911 led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen brought down the absolute monarchy that had reigned over China for thousands of years, but it failed to change the semi-colonial and semi-feudal nature of Chinese society and to alter the bitter fate of the Chinese people. China was in urgent need of new ideas to lead the movement to save the nation and a new organization to rally forces of revolution.

With the salvoes of Russia’s October Revolution in 1917, Marxism-Leninism was brought to China. The May 4th Movement of 1919 spurred the spread of Marxism throughout the country. Then in July 1921, as the Chinese people and the Chinese nation were undergoing a great awakening and Marxism-Leninism was becoming closely integrated with the Chinese workers’ movement, the Communist Party of China was born. The founding of a communist party in China was an epoch-making event, and from then on the Chinese revolution took on an entirely new look.

The Party was keenly aware that the conflicts between imperialism and the Chinese nation, and those between feudalism and the people constituted the principal contradiction in modern Chinese society. To realize national rejuvenation, it would be essential to initiate an anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggle.

In the early days of the Party and during the Great Revolution, the Party formulated the program of the democratic revolution, launched movements of workers, youths, peasants, and women, promoted and supported the reorganization of the Chinese Kuomintang (KMT) and the founding of the National Revolutionary Army, and led the great anti-imperialist and anti-feudal struggle across the country, bringing about a surge in the Great Revolution.

In 1927, the reactionary clique within the KMT betrayed the revolution, brutally massacring communists and other revolutionaries. Meanwhile, the Right deviationist ideas within the Party represented by Chen Duxiu grew into Right opportunist errors and came to dominate the Party’s leadership. The Party and the people were unable to mount an effective resistance, resulting in a disastrous defeat for the Great Revolution under the surprise attack of a powerful enemy.

During the Agrarian Revolutionary War, the Party realized in light of harsh realities that without revolutionary armed forces, it would be impossible to defeat armed counter-revolutionaries, win the Chinese revolution, and thus change the fate of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation. The Party would need to fight armed counter-revolution with armed revolution.

The Nanchang Uprising of 1927 fired the opening shot of armed resistance against KMT reactionaries. This marked the start of the Communist Party of China’s journey to lead the revolutionary struggle independently, build the people’s armed forces, and seize state power by force. Soon afterwards, the policy of carrying out agrarian revolution and organizing armed uprisings was established at the August 7th Meeting. The Party led the Autumn Harvest Uprising, the Guangzhou Uprising, and uprisings in many other areas. Due to the great disparity in strength between the enemy forces and our own, most of these uprisings ended in failure. The fact of the matter was that in view of objective conditions at the time, the Chinese communists could not follow the example of Russia’s October Revolution and win nationwide revolutionary victory by taking key cities first. The Party urgently needed to find a revolutionary path compatible with China’s actual conditions.

The shift from attacking big cities to advancing into rural areas was a new starting point of decisive importance in the Chinese revolution. Led by Comrade Mao Zedong, soldiers and civilians established the first rural revolutionary base in the Jinggang Mountains, where the Party led the people in overthrowing local despots and redistributing the land. The Gutian Meeting of 1929 established the principles of strengthening the Party ideologically and the military politically. As progress was made in the struggle, the Party established the Central Revolutionary Base as well as the Western Hunan-Hubei, Haifeng-Lufeng, Hubei-Henan-Anhui, Qiongya, Fujian-Zhejiang-Jiangxi, Hunan-Hubei-Jiangxi, Hunan-Jiangxi, Zuojiang-Youjiang, Sichuan-Shaanxi, Shaanxi-Gansu, and Hunan-Hubei-Sichuan-Guizhou bases. In addition, the Party also set up Party organizations and other revolutionary organizations in KMT-controlled areas and launched revolutionary mass struggles.

However, the fifth counter-encirclement and suppression campaign in the Central Revolutionary Base ended in failure as a result of the misguided leadership of Wang Ming’s “Left” dogmatism within the Party. The Red Army was forced to make a strategic shift, and arrived in northern Shaanxi Province after enduring the extraordinarily bitter and arduous journey of the Long March. The errors of the “Left” line caused enormous losses to revolutionary bases as well as revolutionary forces in KMT-controlled areas.

In January 1935, the Political Bureau of the Central Committee convened a meeting in Zunyi on the Long March, at which Comrade Mao Zedong was confirmed as the de facto leader of the Central Committee and the Red Army. The meeting laid the groundwork for establishing the leading position within the Central Committee of the correct Marxist line chiefly represented by Comrade Mao Zedong, as well as for the formation of the first generation of the central collective leadership with Comrade Mao Zedong at its core. The meeting opened a new stage in which the Party would act on its own initiative to address practical problems concerning the Chinese revolution, and saved the Party, the Red Army, and the Chinese revolution at a moment of greatest peril. It also subsequently enabled the Party to defeat Zhang Guotao’s separatism, bring the Long March to a triumphant conclusion, and open up new horizons for the Chinese revolution. The Zunyi Meeting is therefore considered a pivotal turning point in the Party’s history.

After the September 18th Incident in 1931 during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, the conflict between China and Japan gradually overtook domestic class conflict as the issue of primary importance. As Japanese imperialists intensified their aggression against China, the country was plunged into an unprecedented national crisis. The Party was the first to propose that China should fight Japanese aggression with armed resistance, and launched extensive resistance movements. It also facilitated a peaceful settlement of the Xi’an Incident, thus playing a historic role in promoting a second period of cooperation between the KMT and the CPC and the united resistance against Japanese aggression.

Following the July 7th Incident in 1937, the Party implemented the right policy on the Chinese united front against Japanese aggression, and adhered to the line of all-out resistance. It devised and executed the strategic guidelines for a protracted war as well as a whole set of strategies and tactics for a people’s war, opened up vast battlefronts behind enemy lines, and developed bases for the resistance. The Party led the Eighth Route Army, the New Fourth Army, the Northeast United Resistance Army, and other forces of the people’s armed resistance in brave fighting, and they were the pillar of the entire nation’s resistance until the Chinese people finally prevailed. This marked the first time in modern history that the Chinese people had won a complete victory against foreign aggressors in the war of national liberation, and was an important part of the global war against fascism.

During the War of Liberation, as the KMT reactionaries flagrantly launched an all-out civil war, the Party led soldiers and civilians in gradually shifting from active defense to strategic offensive. It secured victories in the Liaoxi-Shenyang, Huai-Hai, and Beiping-Tianjin campaigns as well as the Crossing-the-Yangtze Campaign, advanced triumphantly into the central-south, northwest, and southwest, and wiped out eight million KMT troops, thus overthrowing the reactionary KMT government and the three mountains of imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat-capitalism. With the support of the people, the Party-led people’s army demonstrated heroic mettle and unyielding resolve as they fought to the last against these fierce enemies, making a historic contribution to the victory of the new-democratic revolution.

In the course of the revolutionary struggle, Chinese communists, with Comrade Mao Zedong as their chief representative, adapted the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism to China’s specific realities and developed a theoretical synthesis of China’s unique experience which came from painstaking trials and great sacrifices. They blazed the right revolutionary path of encircling cities from the countryside and seizing state power with military force. They established Mao Zedong Thought, which charted the correct course for securing victory in the new-democratic revolution.

In the course of the revolutionary struggle, the Party carried forward its great founding spirit comprised of the following principles: upholding truth and ideals, staying true to its original aspiration and founding mission, fighting bravely without fear of sacrifice, and remaining loyal to the Party and faithful to the people. The Party initiated and advanced the great project of Party building, introduced the principle of focusing on strengthening the Party in ideological terms, and upheld democratic centralism. It stuck to the three fine styles of conduct, namely combining theory with practice, maintaining close ties with the people, and conducting criticism and self-criticism; it developed the three important tools of the united front, armed struggle, and Party building, as it strived to build a national Marxist party of the people, which was fully consolidated in ideological, political, and organizational terms. The rectification movement—a Party-wide Marxist ideological education movement—was launched in 1942 and yielded tremendous results. The Party formulated the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party, which helped the entire Party reach a common understanding of the basic questions regarding the Chinese revolution. At the Seventh National Congress, the correct line, principles, and policies were formulated for building a new-democratic China, and as a result the Party became united as never before in ideological, political, and organizational terms.

On October 1, 1949, the founding of the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed after 28 years of bitter and courageous struggle carried out by the people under the leadership of the Party and with the active support of other political parties and democrats without party affiliation, thus realizing the independence of the Chinese nation and the liberation of the Chinese people. This put an end to China’s history as a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society, to the rule of a handful of exploiters over the working people, to the state of total disunity that plagued the old China, and to all the unequal treaties imposed on our country by foreign powers and all the privileges that imperialist powers enjoyed on our land, marking the country’s great transformation from a millennia-old feudal autocracy to a people’s democracy. This also reshaped the world political landscape and offered enormous inspiration for oppressed nations and peoples struggling for liberation around the world.

It has been proven through practice that history and the people have chosen the Communist Party of China, and that without its leadership, it would not have been possible to realize national independence and the people’s liberation. Through tenacious struggle, the Party and the people showed the world that the Chinese people had stood up and the time in which the Chinese nation could be bullied and abused was gone and would never return. This marked the beginning of a new epoch in China’s development.

II. Socialist Revolution and Construction

In the period of socialist revolution and construction, the main tasks of the Party were to realize the transformation from new democracy to socialism, carry out socialist revolution, promote socialist construction, and lay down the fundamental political conditions and the institutional foundations necessary for national rejuvenation.

After the founding of the People’s Republic, the Party led the people in surmounting a multitude of political, economic, and military challenges. It cleared out bandits and remnant KMT reactionary forces, peacefully liberated Tibet, and unified the entire mainland. It stabilized prices, unified standards for finances and the economy, completed the agrarian reform, and launched democratic reforms in all sectors of society. It introduced the policy of equal rights for men and women, suppressed counter-revolutionaries, and launched movements against the “three evils” of corruption, waste, and bureaucracy and against the “five evils” of bribery, tax evasion, theft of state property, cheating on government contracts, and stealing of economic information. As the stains of the old society were wiped out, China took on a completely new look.

Meanwhile, the Chinese People’s Volunteers marched valiantly across the Yalu River to fight alongside the Korean people and troops. They ultimately defeated a powerful enemy that was armed to the teeth, demonstrating the gallantry of our army and our country, and the unyielding spirit of our people. China’s resounding victory in the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea safeguarded the security of the nascent People’s Republic, and testified to its status as a major country. The new China thus gained a firm foothold amid complex domestic and international environments.

Under the Party’s leadership, a government of people’s democratic dictatorship was established and consolidated, which was led by the working class and based on an alliance of workers and peasants. This created the conditions necessary for the country’s rapid development.

In 1949, the Common Program of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) was passed at the CPPCC’s first plenary session. In 1953, the Party officially set forth the general line for the transition period, namely gradually realizing the country’s socialist industrialization and socialist transformation of agriculture, handicrafts, and capitalist industry and commerce over a fairly long period of time. In 1954, the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China was adopted at the first session of the First National People’s Congress. In 1956, China basically completed the socialist transformation of private ownership of the means of production, and put into practice public ownership of the means of production and distribution according to work, thus marking the establishment of the socialist economic system.

Under the Party’s leadership, China established the system of people’s congresses, the system of CPC-led multiparty cooperation and political consultation, and the system of regional ethnic autonomy, providing institutional guarantees for ensuring that it is the people who run the country. Under the Party’s leadership, China also forged and strengthened unity among people of all ethnic groups, established and developed socialist ethnic relations based on equality and mutual assistance, and achieved and cemented unity between workers, peasants, intellectuals, and people from other social strata across the country. As a result, a broad united front was consolidated and expanded. The establishment of the socialist system laid the foundation for all of China’s subsequent progress and development.

In light of the domestic situation following socialist transformation, the Party propounded at its Eighth National Congress that the main contradiction in China was no longer the contradiction between the working class and the bourgeoisie, but rather that between the demand of the people for rapid economic and cultural development and the reality that the country’s economy and culture fell short of the needs of the people. Therefore, the major task facing the nation was to concentrate on developing the productive forces and realize industrialization in order to gradually meet the people’s growing material and cultural needs. The Party called on the people to redouble their efforts to build China step by step into a strong socialist country with modern agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology, and it led them in carrying out large-scale socialist construction across the board.

Through the execution of several five-year plans, an independent and relatively complete industrial system and national economic framework were established, the conditions of agricultural production were markedly improved, and impressive progress was made in social programs such as education, science, culture, health, and sports. With continuous breakthroughs in cutting-edge technologies, including nuclear weapons, missiles, and satellites, China’s defense industries underwent steady growth after starting from scratch. The People’s Liberation Army continued to grow in strength, expanding from ground forces alone into a composite military force comprised of the navy, air force, and other specialized units. This provided firm support for the People’s Republic to consolidate the newborn people’s government, establish China’s position as a major country, and defend the nation’s dignity.

The Party adhered to an independent foreign policy of peace, championed and upheld the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, and firmly defended China’s independence, sovereignty, and dignity. It provided support and assistance for other oppressed nations in seeking liberation, for newly independent countries in their pursuit of development, and for various peoples as they put up just struggles, and stood opposed to imperialism, hegemonism, colonialism, and racism. The humiliating diplomacy of the old China was put to an end.

The Party adjusted its diplomatic strategies in light of evolving circumstances, worked to restore all lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations, opened up new horizons for China’s diplomacy, and fostered commitment to the one-China principle among the international community. The Party put forward the theory of the differentiation of the three worlds and made the promise that China would never seek hegemony, earning respect and acclaim from the international community and developing countries in particular.

The Party fully foresaw the new challenges it would face after assuming power over the whole country. As early as at the second plenary session of its Seventh Central Committee which was held shortly before nationwide victory was attained in the War of Liberation, the Party called on all members to remain modest, prudent, and free from arrogance and rashness in their work, and to preserve the style of plain living and hard struggle. After the founding of the People’s Republic, the Party focused on the major issue of Party building in the context of governing, and worked to strengthen the Party and consolidate Party leadership ideologically, organizationally, and in terms of conduct. The Party bolstered efforts to encourage officials to study theory and increase their knowledge, improved its capacity for exercising leadership, and demanded that all members, especially high-ranking officials, act with a greater sense of purpose to safeguard Party unity and solidarity. Rectification campaigns were carried out throughout the Party to strengthen education within the Party, consolidate primary-level organizations, raise membership requirements, and oppose bureaucratism, commandism, graft, and waste. The Party was on high alert against corruption, worked hard to prevent degeneracy among officials, and responded to corruption with firm punishment. These important measures strengthened the integrity of the Party and the solidarity of all Party members, built closer ties between the Party and the people, and accumulated essential starting experience for building a governing party.

During this period, Comrade Mao Zedong proposed a second round of efforts to integrate the basic tenets of Marxism-Leninism with China’s realities. Chinese communists, with Comrade Mao Zedong as their chief representative, enriched and developed Mao Zedong Thought by taking stock of new realities, and put forward a series of important theories for socialist construction. These included recognizing that socialist society was a long historical period; strictly differentiating between two types of contradictions, namely those between the people and the enemy and those among the people, and properly dealing with these contradictions; handling the ten major relationships in China’s socialist construction appropriately; finding a path to industrialization suited to China’s realities; respecting the law of value; implementing the principle of long-term coexistence and mutual oversight between the Communist Party and other political parties; and applying the principle of letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend to scientific and cultural work. These creative theoretical achievements maintain important guiding significance to this day.

Mao Zedong Thought represents a creative application and advancement of Marxism-Leninism in China. It is a summation of theories, principles, and experience on China’s revolution and construction that has been proven correct through practice, and its establishment marked the first historic step in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context. The living soul of Mao Zedong Thought is the positions, viewpoints, and methods embodied in its constituent parts, which are reflected in three basic points—seeking truth from facts, following the mass line, and staying independent. These have provided sound guidance for developing the cause of the Party and the people.

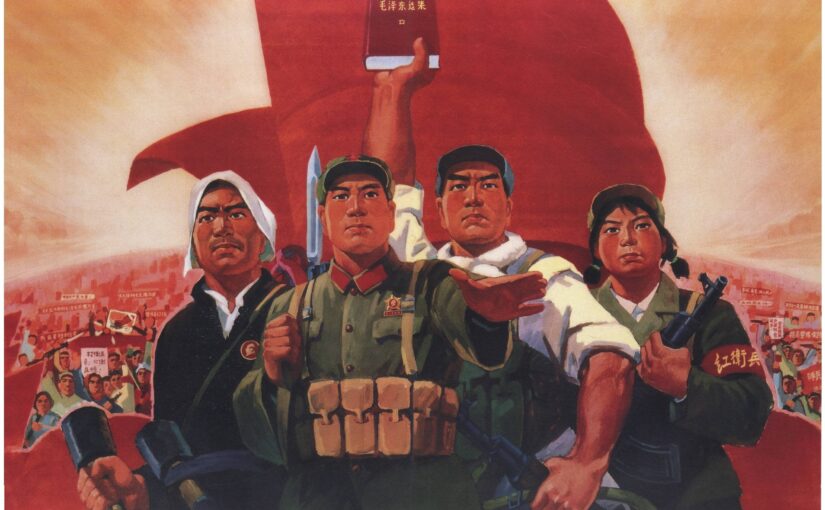

Regrettably, the correct line adopted at the Party’s Eighth National Congress was not fully upheld. Mistakes were made such as the Great Leap Forward and the people’s commune movement, and the scope of the struggle against Rightists was also made far too broad. Confronted with a grave and complex external environment at the time, the Party was extremely concerned about consolidating China’s socialist state power, and made a wide range of efforts in this regard. However, Comrade Mao Zedong’s theoretical and practical errors concerning class struggle in a socialist society became increasingly serious, and the Central Committee failed to rectify these mistakes in good time. Under a completely erroneous appraisal of the prevailing class relations and the political situation in the Party and the country, Comrade Mao Zedong launched and led the Cultural Revolution. The counter-revolutionary cliques of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing took advantage of Comrade Mao Zedong’s mistakes, and committed many crimes that brought disaster to the country and the people, resulting in ten years of domestic turmoil which caused the Party, the country, and the people to suffer the most serious losses and setbacks since the founding of the People’s Republic. This was an extremely bitter lesson. Acting on the will of the Party and the people, the Political Bureau of the Central Committee resolutely smashed the Gang of Four in October 1976, putting an end to the catastrophic Cultural Revolution.

From the founding of the People’s Republic to the eve of reform and opening up, the Party led the people in completing the socialist revolution, eliminating all systems of exploitation, and bringing about the most extensive and profound social change in the history of the Chinese nation and a great transformation from a poor and backward Eastern country with a large population to a socialist country. Despite the serious setbacks it encountered in the process of exploration, the Party made creative theoretical achievements and great progress in socialist revolution and construction, which provided valuable experience, theoretical preparation, and material foundations for launching socialism with Chinese characteristics into a new historical period.

Through tenacious struggle, the Party and the people showed the world that the Chinese people were not only capable of dismantling the old world, but also of building a new one, that only socialism could save China, and that only socialism could develop China.

III. Reform, Opening Up, and Socialist Modernization

In the new period of reform, opening up, and socialist modernization, the main tasks facing the Party were to continue exploring a right path for building socialism in China, unleash and develop the productive forces, lift the people out of poverty and help them become prosperous in the shortest time possible, and fuel the push toward national rejuvenation by providing new, dynamic institutional guarantees as well as the material conditions for rapid development.

After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Party stood at a crucial historical juncture in which it was confronted with the question of which course the Party and the country should take. The Party came to recognize that the only way forward was to launch a program of reform and opening up; otherwise, our endeavors in pursuing modernization and building socialism would be doomed to failure. In December 1978, the 11th Central Committee held its third plenary session. At the session the Party decisively abandoned the policy of taking class struggle as the key link, and initiated a strategic shift in the focus of the Party and country’s work, thereby ushering in a new period of reform, opening up, and socialist modernization. This marked a great turning point of far-reaching significance in the Party’s history since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The Party also made the momentous decision to completely renounce the Cultural Revolution. Over the more than 40 years that have passed since then, the Party has never wavered in following the line, principles, and policies adopted at this session.

After the third plenary session of the 11th Central Committee, Chinese communists, with Comrade Deng Xiaoping as their chief representative, united and led the whole Party and the entire nation in conducting a thorough review of the experience gained and lessons learned since the founding of the People’s Republic. On this basis, and by focusing on the fundamental questions of what socialism is and how to build it and drawing lessons from the history of world socialism, they established Deng Xiaoping Theory, and devoted their efforts to freeing minds and seeking truth from facts. The historic decision was made to shift the focus of the Party and the country’s work onto economic development and to launch the reform and opening up drive. Chinese communists brought the essence of socialism to light, set the basic line for the primary stage of socialism, and made it clear that China would follow its own path and build socialism with Chinese characteristics. They provided sensible answers to a series of basic questions on building socialism with Chinese characteristics, and formulated a development strategy for basically achieving socialist modernization by the middle of the 21st century through a three-step approach. They thus succeeded in founding socialism with Chinese characteristics.

After the fourth plenary session of the 13th Central Committee, Chinese communists, with Comrade Jiang Zemin as their chief representative, united and led the whole Party and the entire nation in upholding the Party’s basic theory and line, deepening their understanding of what socialism is and how to build it, and what kind of party to build and how to build it. On this basis, they formed the Theory of Three Represents. In the face of complex domestic and international situations and serious setbacks confronting world socialism, they safeguarded socialism with Chinese characteristics, defined building a socialist market economy as an objective of reform and set a basic framework in this regard, and established a basic economic system for the primary stage of socialism under which public ownership is the mainstay and diverse forms of ownership develop together, as well as an income distribution system under which distribution according to work is the mainstay while multiple forms of distribution exist alongside it. They opened up new horizons for reform and opening up across all fronts and advanced the great new project of Party building. All these efforts helped to successfully launch socialism with Chinese characteristics into the 21st century.

After the 16th National Congress, Chinese communists, with Comrade Hu Jintao as their chief representative, united and led the whole Party and the entire nation in advancing practical, theoretical, and institutional innovation during the process of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. They gained a deep understanding of major questions such as what kind of development to pursue and how to pursue it under new circumstances, and provided clear answers to these questions, thus forming the Scientific Outlook on Development. Taking advantage of an important period of strategic opportunity, they focused their energy on development, with emphasis on pursuing comprehensive, balanced, and sustainable development that put the people first. They worked hard to ensure and improve people’s wellbeing, promote social fairness and justice, bolster the Party’s governance capacity, and maintain its advanced nature. In doing so, they succeeded in upholding and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics under new circumstances.

In order to promote reform and opening up, the Party re-established the Marxist ideological, political, and organizational lines, thoroughly refuted the erroneous “two whatevers” policy, and correctly appraised the historical position of Comrade Mao Zedong and the value of Mao Zedong Thought as a scientific system. The Party made it clear that the principal contradiction in Chinese society was that China’s underdeveloped social production was unable to meet the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people, and hence the central task of the Party was to resolve this contradiction. On this basis, the Party put forward the goal of building China into a moderately prosperous society.

The Party restored and formulated a series of correct policies in all fields of work, and began the process of readjusting the national economy. Under the leadership of the Party, comprehensive steps were taken to set things right ideologically, politically, and organizationally, and extensive efforts were made to redress wrongs suffered by those who were unjustly, falsely, and wrongly accused and to regulate social relations. The adoption of the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China marked the successful conclusion of the Party’s efforts to rectify its guiding principles.

The Party came to recognize that to open up new prospects for reform, opening up, and socialist modernization, it needed to steer the advancement of its endeavors with theoretical innovation. Comrade Deng Xiaoping once said, “When everything has to be done by the book, when thinking turns rigid and blind faith is the fashion, it is impossible for a party or a nation to make progress. Its life will cease and that party or nation will perish.” With this understanding, the Party led and supported extensive discussions on the criterion for testing truth, upheld and developed Marxism in light of new practices and the features of the times, and effectively answered a series of basic questions regarding socialism with Chinese characteristics, including development path, stage of development, fundamental tasks, development drivers, development strategies, political guarantee, national reunification, diplomacy and international strategy, leadership, and forces to rely on, thereby forming the theory of socialism with Chinese characteristics and achieving a new breakthrough in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context.

At its 12th through 17th national congresses, the Party made consistent overall plans for advancing reform, opening up, and socialist modernization in view of evolving circumstances at home and abroad and new requirements for the country’s development. The Central Committee convened several plenary sessions dedicated to planning major initiatives for promoting reform, development, and stability.

The introduction of the household contract responsibility system in rural areas marked the initial breakthrough in China’s reform, further steps were gradually taken to reform the economic structure in the cities, and reform initiatives were then carried out across the board. Oriented toward the development of a socialist market economy, this reform gave greater and broader play to the basic role of market in allocating resources, while upholding and improving China’s basic economic and income distribution systems. While resolutely advancing economic structural reform, the Party simultaneously carried out political, cultural, and social structural reforms as well as institutional reforms related to Party building, which led to the formation and development of vigorous institutions and mechanisms that suited the conditions of contemporary China.

The Party designated opening up as a fundamental national policy. Under this policy, China progressed from establishing special economic zones in Shenzhen and a few other areas to opening up more parts of the country–Pudong in Shanghai, key inland cities as well as areas along the coastline, borders, the Yangtze River, and major transportation routes. It also acceded to the World Trade Organization, and went from “bringing in” to “going global.” In this process, we fully utilized both domestic and international markets and resources.

With continuous progress in reform and opening up, China achieved the historic transformations from a highly centralized planned economy into a socialist market economy brimming with vitality, and from a country that was largely isolated into one that is open to the outside world across the board.

In an effort to accelerate socialist modernization, the Party led the people in promoting economic, political, cultural, and social development and made immense achievements.

The Party continued to take economic development as the central task, stood by the conviction that development is of paramount importance, and put forward the notion that science and technology constitute the primary productive force. It implemented major strategies such as invigorating China through science and education, pursuing sustainable development, and developing a quality workforce. It advanced large-scale development of the western region, revitalized old industrial bases in the northeast and other regions, promoted the rise of the central region, and supported the trailblazing development of the eastern region in an effort to promote the coordinated development of urban and rural areas and different regions. The Party promoted the reform and development of state-owned enterprises, encouraged and supported the development of the non-public sector, and accelerated the transformation of the economic growth model. It stepped up environmental protection and promoted sustained and rapid economic development. All of this enabled China’s composite national strength to increase by a large margin.

Upholding the unity between the Party’s leadership, the running of the country by the people, and law-based governance, the Party worked to develop socialist democracy and promote socialist political progress and advanced reform of the political system in a proactive and prudent manner. With a commitment to integrating the rule of law with the rule of virtue, a new Constitution of the People’s Republic of China was formulated, China built itself into a socialist country under the rule of law, and a socialist system of laws with Chinese characteristics took shape. The Party made earnest efforts to respect and protect human rights and consolidated and developed the broadest possible patriotic united front.

The Party stepped up education on ideals and convictions, advanced the development of the core socialist values, promoted cultural-ethical progress, and fostered an advanced socialist culture, thus pushing socialist culture to flourish.

The Party accelerated social development with a focus on improving public wellbeing. It worked to improve people’s living standards and rescinded taxes on agriculture. It devoted constant effort to ensuring access to education, employment, medical services, elderly care, and housing and to promoting social harmony and stability.

The Party put forward the overall goal of building a strong, modern, and standardized revolutionary military, and it made winning local wars in the information age the focal point in preparation for military struggle. It advanced military transformation with Chinese characteristics by following an approach of having fewer but better troops.

Facing a rapidly changing international landscape, the Party upheld the Four Cardinal Principles, eliminated all kinds of interference, and calmly responded to a series of risks and trials related to China’s overall reform, development, and stability.

The late 1980s and early 1990s witnessed the demise of the Soviet Union and the drastic changes in Eastern European countries. In the late spring and early summer of 1989, a severe political disturbance took place in China as a result of the international and domestic climates at the time, and was egged on by hostile anti-communist and anti-socialist forces abroad. With the people’s backing, the Party and the government took a clear stand against the turmoil, defending China’s socialist state power and safeguarding the fundamental interests of the people.

The Party led the people in successfully responding to the Asian financial crisis, the global financial crisis, and other economic risks. We successfully held the 2008 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Beijing. We overcame natural disasters, such as severe flooding on the Yangtze, Nenjiang, and Songhua rivers, the devastating earthquake in Wenchuan, and the SARS epidemic. All these victories demonstrated the Party’s ability to withstand risks and cope with complicated situations.

Defining national reunification as a major historical task, the Party worked tirelessly to complete it. Comrade Deng Xiaoping introduced the creative and well-conceived concept of One Country, Two Systems, paving a new path for achieving reunification through peaceful means.

Through arduous work and struggle, the Chinese government successively resumed its exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong and Macao, thus ending a century-long history of humiliation. Since Hong Kong and Macao’s return to the motherland, the central government acted in strict compliance with China’s Constitution and the basic laws of the special administrative regions and maintained lasting prosperity and stability in the two regions.

Keeping in mind the big picture with regard to resolving the Taiwan question, the Party set forth the basic principles of peaceful reunification and One Country, Two Systems and facilitated agreement across the Taiwan Strait on the 1992 Consensus, which embodies the one-China principle. It advanced cross-Strait consultations and negotiations, established comprehensive and direct two-way mail, transport, and trade links across the Strait, and launched dialogues between political parties of the two sides. The Party pushed for the enactment of the Anti-Secession Law, resolutely deterred separatist forces seeking “Taiwan independence,” promoted national reunification, and thwarted attempts to create “two Chinas,” “one China, one Taiwan,” or “Taiwan independence.”

Based on a judicious assessment of global trends and the features of the era, the Party put forward the concept that peace and development are the themes of our times. In line with this concept, China upheld its fundamental foreign policy goal of preserving world peace and promoting shared development. It adjusted its relations with other major countries, developed friendly relations with neighboring countries, and deepened friendly cooperation with other developing countries. It actively participated in international and regional affairs and created a new comprehensive and multi-layered framework for foreign relations.

The Party promoted the development of a multipolar world and the democratization of international relations and pushed economic globalization in a direction toward common prosperity. China took an unequivocal stand against hegemonism and power politics, endeavored to safeguard the interests of developing countries, worked for a new international political and economic order that would be fair and equitable, and promoted lasting peace and common prosperity in the world.

The Party has always stressed that to do a good job of governing the country, we must first do a good job of governing the Party, and that means governing it strictly. With this in mind, it focused its efforts on strengthening the Party and launched the great new project of Party building.

The Party formulated the Code of Conduct for Intraparty Political Life, strengthened democratic centralism, promoted democracy within the Party, and normalized intraparty political activities. It launched a party-wide rectification campaign through a well-planned, step-by-step approach in order to address the problems of defects in terms of thinking, conduct, and organization within the Party. The Party also worked to fortify its ranks with the aim of cultivating younger, more revolutionary, better educated, and more specialized officials, and it made a strong point of promoting young and middle-aged officials and advancing the process of succession.

With a view to addressing the two historical challenges of improving the Party’s leadership and governance and bolstering its ability to resist corruption, prevent moral decline, and withstand risks, and with its focus on enhancing its governance capacity and advanced nature, the Party made a series of decisions on major issues including strengthening its ties with the people, its style of work, and its governance capacity. It also carried out education campaigns on the importance of study, political integrity, and rectitude, on the Theory of Three Represents, on preserving the advanced nature of Party members, and on studying and applying the Scientific Outlook on Development. The Party defined efforts to improve Party conduct, uphold integrity, and combat corruption as issues concerning the very survival of the Party and the country, and pushed forward the development of systems for preventing and punishing corruption.

On the 40th anniversary of the launch of reform and opening up, the Party held a grand ceremony to mark this important event. In his address at the ceremony, Comrade Xi Jinping reviewed the great achievements made and valuable experience accumulated over those four decades. He stressed that reform and opening up represented a great awakening for the Party and a great revolution in the history of the Chinese nation’s development, and he called for continued efforts to see this process through. Our country’s impressive achievements in reform, opening up, and modernization attracted the whole world’s attention. China achieved the historic transformation from a country with relatively backward productive forces to the world’s second largest economy, and made the historic strides of raising the living standards of its people from bare subsistence to moderate prosperity in general and then toward moderate prosperity in all respects. All these achievements marked the tremendous advance of the Chinese nation from standing up to growing prosperous.

Through tenacious struggle, the Party and the people showed the world that reform and opening up was a crucial move in making China what it is today, that socialism with Chinese characteristics is the correct road that has led the country toward development and prosperity, and that China has caught up with the times in great strides.

IV. A New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics

Following the Party’s 18th National Congress, socialism with Chinese characteristics entered a new era. The main tasks facing the Party in this period are to fulfill the First Centenary Goal, embark on the new journey to accomplish the Second Centenary Goal, and continue striving toward the great goal of national rejuvenation.

The Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core has implemented the national rejuvenation strategy within the wider context of once-in-a-century changes taking place in the world. It has stressed that the new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics is an era in which we will build on past successes to further advance our cause and continue to strive for the success of socialism with Chinese characteristics under new historical conditions; an era in which we will use the momentum of our decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects to fuel all-out efforts to build a great modern socialist country; an era in which Chinese people of all ethnic groups will work together to create a better life for themselves and gradually realize the goal of common prosperity; an era in which all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation will strive with one heart to realize the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation; and an era in which China will make even greater contributions to humanity. This new era is a new historic juncture in China’s development.

Chinese communists, with Comrade Xi Jinping as their chief representative, have established Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era on the basis of adapting the basic tenets of Marxism to China’s specific realities and its fine traditional culture, upholding Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, and the Scientific Outlook on Development, thoroughly reviewing and fully applying the historical experience gained since the founding of the Party, and proceeding from new realities.

Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era makes the following clear:

—The leadership of the Communist Party of China is the defining feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics and the greatest strength of the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and that the Party is the highest force for political leadership. Therefore, all Party members must strengthen their consciousness of the need to maintain political integrity, think in big-picture terms, follow the leadership core, and keep in alignment with the central Party leadership; stay confident in the path, theory, system, and culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics; and uphold Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Party Central Committee and in the Party as a whole, and uphold the Central Committee’s authority and its centralized, unified leadership.

—The overarching task of upholding and developing socialism with Chinese characteristics is to realize socialist modernization and national rejuvenation, and that on the basis of completing the goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects, a two-step approach should be taken to build China into a great modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced, harmonious, and beautiful by the middle of the 21st century, and to promote national rejuvenation through a Chinese path to modernization.

—The principal contradiction facing Chinese society in the new era is that between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life, and the Party must therefore remain committed to a people-centered philosophy of development, develop whole-process people’s democracy, and make more notable and substantive progress toward achieving well-rounded human development and common prosperity for all.

—The integrated plan for building socialism with Chinese characteristics covers five spheres, namely economic, political, cultural, social, and ecological advancement, and that the comprehensive strategy in this regard includes four prongs, namely building a modern socialist country, deepening reform, advancing law-based governance, and strengthening Party self-governance.

—The overall objectives of comprehensively deepening reform are to develop and improve the system of socialism with Chinese characteristics and to modernize China’s system and capacity for governance.

—The overall goal of comprehensively advancing law-based governance is to establish a system of socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics and to build a socialist rule of law country.

—China must uphold and improve its basic socialist economic system, see that the market plays the decisive role in resource allocation and the government plays its role better, have an accurate understanding of this new stage of development, apply a new philosophy of innovative, coordinated, green, open, and shared development, accelerate efforts to foster a new pattern of development that is focused on the domestic economy but features positive interplay between domestic and international economic flows, promote high-quality development, and balance development and security imperatives.

—The Party’s goal for military development in the new era is to build the people’s armed forces into world-class forces that obey the Party’s command, that are able to fight and to win, and that maintain excellent conduct.

—Major-country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics aims to serve national rejuvenation, promote human progress, and facilitate efforts to foster a new type of international relations and build a human community with a shared future.

—Full and rigorous self-governance is a policy of strategic importance for the Party, and the general requirements for Party building in the new era include making all-around efforts to strengthen the Party in political, ideological, and organizational terms and in terms of conduct and discipline, with institution building incorporated into every aspect of this process, continuing the fight against corruption, and ensuring that the political responsibility for governance over the Party is fulfilled. By engaging in great self-transformation, the Party can steer great social transformation.

These strategic concepts and innovative ideas are the important outcomes of the Party’s theoretical development based on a deeper understanding of the underlying laws of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

Comrade Xi Jinping, through meticulous assessment and deep reflection on a number of major theoretical and practical questions regarding the cause of the Party and the country in the new era, has set forth a series of original new ideas, thoughts, and strategies on national governance revolving around the major questions of our times: what kind of socialism with Chinese characteristics we should uphold and develop in this new era, what kind of great modern socialist country we should build, and what kind of Marxist party exercising long-term governance we should develop, as well as how we should go about achieving these tasks. He is thus the principal founder of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. This is the Marxism of contemporary China and of the 21st century. It embodies the best of the Chinese culture and ethos in our times and represents a new breakthrough in adapting Marxism to the Chinese context. The Party has established Comrade Xi Jinping’s core position on the Party Central Committee and in the Party as a whole, and defined the guiding role of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. This reflects the common will of the Party, the armed forces, and Chinese people of all ethnic groups, and is of decisive significance for advancing the cause of the Party and the country in the new era and for driving forward the historic process of national rejuvenation.

The significant achievements attained in the cause of the Party and the country since the launch of reform and opening up have laid a solid foundation and created favorable conditions for developing socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era. At the same time, however, the Party has remained soberly aware that changes in the international environment have brought about many new risks and challenges and China faces no small number of long unresolved, deep-seated problems as well as newly emerging problems regarding reform, development, and stability. Moreover, previously lax and weak governance has enabled inaction and corruption to spread within the Party and led to serious problems in its political environment, which has harmed relations between the Party and the people and between officials and the public, weakened the Party’s creativity, cohesiveness, and ability, and posed a serious test to its exercise of national governance.

The Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core has demonstrated great historical initiative, tremendous political courage, and a powerful sense of mission. Keeping in mind both domestic and international imperatives, the Central Committee has implemented the Party’s basic theory, line, and policy and provided unified leadership for advancing our great struggle, great project, great cause, and great dream. Acting on the general principle of pursuing progress while ensuring stability, it has introduced a raft of major principles and policies, launched a host of major initiatives, pushed ahead with many major tasks, and overcome a number of major risks and challenges. It has solved many tough problems that were long on the agenda but never resolved and accomplished many things that were wanted but never got done. With this, it has prompted historic achievements and historic shifts in the cause of the Party and the country.

1. Upholding the Party’s overall leadership

Since the launch of reform and opening up, the Party has made continued efforts to strengthen and improve its leadership, providing fundamental political guarantees for the cause of the Party and the country. However, there have remained many problems within the Party with respect to upholding its leadership such as a lack of clear awareness and vigorous action as well as weak, ineffective, diluted, and marginalized efforts in implementation. In particular, the Central Committee’s major decisions and plans were not properly executed as some officials selectively implemented the Party’s policies or even feigned agreement or compliance and did things their own way.

The Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core has made it clear that the leadership of the Party is the foundation and lifeblood of the Party and the country, and the pillar upon which the interests and wellbeing of all Chinese people depend. All Party members must maintain a high degree of unity with the Central Committee ideologically, politically, and in action. We need to enhance our capacity to conduct sound, democratic, and law-based governance, and ability to chart our course, craft overall plans, design policy, and promote reform. We must ensure that the Party fully exerts its core role in providing overall leadership and coordinating the efforts of all sides.

The Party has clearly stated that it exercises overall, systemic, and integrated leadership, and that its lifeblood lies in maintaining its solidarity and unity. The centralized, unified leadership of the Central Committee is the highest principle of the Party’s leadership, and upholding and strengthening this is the common political responsibility of each and every Party member. In upholding Party leadership, all Party members must, first and foremost, take a clear stance in maintaining political integrity to ensure that the whole Party obeys the Central Committee.

The Code of Conduct for Intraparty Political Life under New Circumstances was approved at the sixth plenary session of the 18th Central Committee. The regulations of the Political Bureau on upholding and strengthening the centralized, unified leadership of the Central Committee were also issued. These documents were designed to strictly enforce the Party’s political rules and discipline, to counteract and prevent self-centered behavior, decentralism, liberalism, departmentalism, and the “nice-guy” mentality, to cultivate a positive and healthy intraparty political culture, and to foster a sound political ecosystem featuring honesty and integrity within the Party.

The Central Committee has required leading officials to improve their capacity for political judgment, thinking, and implementation; to remain mindful of the country’s most fundamental interests; and to be loyal to the Party, obey its command, and fulfill their duties to it.

The Party has strengthened its leadership systems. It has improved the institutions for Party leadership over the people’s congresses, the government, the CPPCC, the supervisory, judicial, and procuratorial organs of the state, the armed forces, people’s organizations, enterprises and public institutions, primary-level people’s organizations for self-governance, and social organizations, thereby ensuring that the Party plays its role of providing leadership in all these organizations.

The Party has practiced democratic centralism. It has put in place sound systems for ensuring its leadership over major work of the state. The functions and roles of the Central Committee’s decision-making, deliberative, and coordinating institutions have been strengthened, and the mechanisms for ensuring implementation of the Central Committee’s major policies have been improved. The Party has strictly implemented the system for requesting instructions from and submitting reports to the Central Committee; tightened political oversight and inspection; investigated and handled cases of deviation from the Party’s line, principles, and policies as well as instances in which the Party’s centralized, unified leadership has been undermined; and rid the Party of members who acted duplicitously. All these measures have helped ensure that the whole Party maintains a high degree of unity with the Central Committee in terms of political stance, political orientation, political principles, and political path.

Since the 18th National Congress, the Party Central Committee’s authority and its centralized, unified leadership have remained robust, the Party’s leadership systems have improved, and the way in which the Party exercises its leadership has become more refined. There is greater unity among all Party members in terms of thinking, political resolve, and action, and the Party has significantly boosted its capacity to provide political leadership, give guidance through theory, organize the people, and inspire society.

2. Exercising full and rigorous self-governance

Since the launch of reform and opening up, the Party has upheld the principle of the Party exercising effective self-supervision and practicing strict self-governance, making notable progress in Party building.

However, there was a certain period in which we failed to supervise Party organizations effectively or govern them with the necessary stringency. This resulted in a serious lack of political conviction among some Party members and officials, misconduct in the selection and appointment of personnel in some localities and government departments, a blatant culture of pointless formalities, bureaucratism, hedonism, and extravagance, and a prevalence of privilege-seeking attitudes and behavior. To be more specific, some officials engaged in cronyism and ostracized those outside of their circle; some formed self-serving cliques; some anonymously lodged false accusations and fabricated rumors; some sought to buy popular support and rig elections in their favor; some promised official posts and lavished praise on each other for their promotions; some did things their own way and feigned compliance with policies while acting counter to them; and some got too big for their boots and made presumptuous comments on the decisions of the Central Committee. Such misconduct interwoven with political and economic issues led to a startling level of corruption that damaged the Party’s image and prestige and severely undermined relations between the Party and the people and between officials and the people, arousing the discontent and indignation of many Party members, officials, and members of the public.

Comrade Xi Jinping emphasized that it takes a good blacksmith to make good steel and that China’s success hinges on the Party, especially on the Party’s efforts to exercise effective self-supervision and full and rigorous self-governance. With this understanding, we must make strengthening the Party’s long-term governance capacity and its advanced nature and integrity the main tasks, make enhancing the Party politically the guiding principle, make firm commitment to the Party’s ideals, convictions, and purpose the foundation, and make harnessing the whole Party’s enthusiasm, initiative, and creativity the focus of our efforts. We must keep improving the efficacy of Party building and build the Party into a vibrant Marxist governing party that stays at the forefront of the times, enjoys the wholehearted support of the people, has the courage to reform itself, and is able to withstand all tests.

With the attitude and resolve to make Party building an unceasing endeavor, the Party has practiced rigorous self-governance and put the spotlight on leading officials, the “key few.” It has worked to ensure that responsibilities for taking charge and exercising supervision over self-governance are properly fulfilled, bolstered the enforcement of oversight, discipline, and accountability, and integrated the requirement for full and strict self-governance into all aspects of Party building. The Central Committee has convened meetings on Party building in various sectors and made effective plans in this regard, thus promoting all-around progress in Party building.

The Central Committee has consistently stressed that our Party comes from the people, has its roots among the people, and is dedicated to serving the people. Once the Party becomes disengaged from the people, it will lose its vitality. To exercise strict self-governance in all respects, we must first address issues concerning Party conduct that the people are strongly concerned about.

For this purpose, the Central Committee started with formulating and enforcing an eight-point decision on improving Party and government conduct and worked to improve the Party’s style of work through a top-down approach, with members of the Political Bureau and leading officials taking the lead. The Political Bureau holds meetings every year to hear reports on implementation of the eight-point decision and to engage in criticism and self-criticism on this subject.

With the persistence to keep hammering away, the Central Committee has made consistent efforts to tackle pointless formalities, bureaucratism, hedonism, and extravagance. It has opposed privilege-seeking attitudes and behavior, shut down extravagant and wasteful spending and use of public funds for non-work-related gifts, dining, or travel, and worked to solve prominent problems that invite a strong public response or harm the public’s interests. The Central Committee has reduced burdens at the primary level, and encouraged frugality while opposing wasteful spending. Thanks to these efforts, certain unhealthy tendencies that were once considered impossible to control have been reined in, and certain problems that had long plagued us have been remedied, while Party, government, and social conduct have significantly improved.

The Party has always stressed that the whole Party must maintain firm ideals and convictions, well-constructed organizational systems, and strict rules and discipline.

Our faith in Marxism, the great ideal of communism, and the common ideal of socialism with Chinese characteristics are our source of strength and the anchor of our political soul as Chinese communists, and they constitute the ideological foundation for maintaining the Party’s unity. The Central Committee has stressed that ideals and convictions are like essential nutrients; without them, we would become frail and susceptible to corruption, greed, degeneracy, and decadence.

The Party has remained committed to integrating efforts to strengthen the Party ideologically with those to bolster self-governance through institutional building. In recent years, it has launched campaigns for advancing study and implementation of the mass line; for pushing Party members to be strict with themselves in practicing self-cultivation, exercising power, and maintaining self-discipline and to be earnest in their thinking, work, and behavior; for requiring Party members to study the Party Constitution, Party regulations, and General Secretary Xi Jinping’s major policy addresses and to meet Party standards; for raising awareness of the need to stay true to the Party’s founding mission; and for encouraging study of the Party’s history. Through these efforts, the Party aims to equip its members with its new theories and to turn itself into a learning party. It has worked to educate and guide Party members and officials, especially leading officials, so that they can keep the roots of their convictions healthy and strong and absorb the mental nutrients they need to maintain the right line in their thinking, and ultimately preserve their political character and the backbone of their identity as communists.

The Party has introduced and implemented an organizational line for the new era. It has specified a set of criteria for good officials, which include firm convictions, devotion to serving the people, a strong and pragmatic work ethic, a willingness to take responsibility, and a commitment to being clean and honest. In appointing officials, the Party has adopted a rational approach with a greater emphasis on political integrity. It has adhered to the principle of selecting officials on the basis of both integrity and ability, with greater weight given to the former, and on the basis of merit regardless of background, and it is intent on appointing those who are dedicated, impartial, and upright. The Party has opposed the selection of officials solely on the basis of votes, assessment scores, GDP growth rates, or age, or through open popularity contests. It has strengthened the role of Party organizations in exercising leadership and final oversight in order to rectify misconduct in the selection and appointment of officials.

The Party has mandated that leading officials at all levels cultivate a proper worldview, outlook on life, and sense of values, all of which serve as the “master switch” for their conduct, and that they appreciate the power entrusted to them, manage it well, and use it prudently. They must willingly submit to the oversight from all sides, share the Party’s concerns at all times, make contributions to the country, and work for the people’s wellbeing.

The Party has adhered to the principle of the Party supervising personnel, pursued a more proactive, open, and effective personnel policy, implemented the strategy of invigorating China by developing a quality workforce in the new era, and moved faster to build world-class hubs for talent and innovation, thus bringing together the brightest minds from all corners.

The Party has constantly strengthened its organizational system with a focus on improving the organizational capacity of Party organizations and enhancing their political and organizational functions. By attaching greater attention to the primary level, the Party has promoted full coverage for its organizational framework and initiatives.

The Party has upheld the principles that Party discipline should be even more stringent than the law and that discipline and law enforcement efforts should go hand in hand. It has conducted four forms of oversight over discipline compliance,[ The four forms are: 1) criticism and self-criticism activities and oral and written inquiries which are to be conducted regularly, to ensure that those who have committed minor misconduct are made to “redden and sweat”; 2) light penalties and minor organizational adjustments to official positions, which are to be applied in the majority of cases; 3) heavy penalties and major adjustments to official positions, which are to be applied in a small number of cases; and 4) investigation and prosecution, which are to be undertaken in a very small number of cases involving serious violations of discipline and suspected criminal activity.] strengthened political and organizational discipline, and promoted stricter observance of discipline on all fronts. The Party has remained committed to exercising rule-based governance over the Party, strictly abided by the Party Constitution, and developed a sound system of intraparty regulations. It has worked to ensure strict compliance with all Party institutions, and to make Party building efforts more rationally-conceived, institutionalized, and procedure-based.

The Central Committee has stressed that corruption is the greatest threat to the Party’s long-term governance. The fight against corruption is a major political struggle that the Party cannot and must not lose. If we let a few hundred corrupt officials slip through the cracks, we would let down all 1.4 billion Chinese people. We must confine power to an institutional cage and ensure that powers are properly defined, standardized, constrained, and subject to oversight in accordance with discipline and the law.

The Party has made integrated efforts to see that officials do not have the opportunity, desire, or audacity to engage in corruption. It has used punishment as a deterrent, strengthened institutional constraints, and promoted heightened consciousness, so as to ensure that the powers conferred by the Party and the people are always used for the people’s benefit. The Party insists that no place is out of bounds, no ground is left unturned, and no tolerance is shown in the fight against corruption. It has imposed tight constraints, maintained a firm stance, and strengthened long-term deterrents against corruption. It has punished both those who take bribes and those who offer them and ensured that every case is investigated and all perpetrators of corruption are punished. The Party has shown the determination to adopt powerful remedies and the courage to take painful measures for the sake of the bigger picture, and taken firm action to “take out tigers,” “swat flies,” and “hunt down foxes.”

The Party has intensified efforts to address corruption that occurs on the people’s doorsteps, hunt down corrupt officials who fled overseas and recover state assets they had stolen, and root out all corrupt officials. The Party has focused on dealing with cases involving both political and economic corruption, prevented interest groups from arising within the Party, and investigated and punished corrupt officials such as Zhou Yongkang, Bo Xilai, Sun Zhengcai, and Ling Jihua for their serious violations of Party discipline and the law.