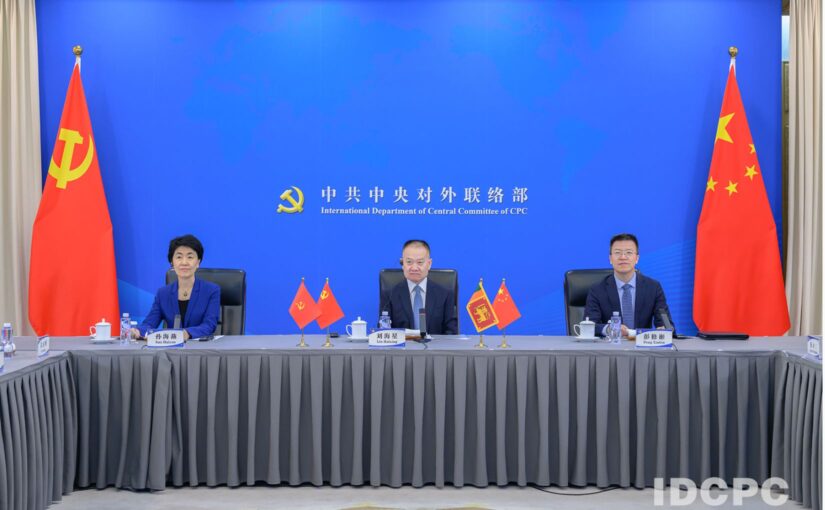

Liu Haixing, Minister of the International Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee (IDCPC), held a video meeting with Tilvin Silva, General Secretary of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) of Sri Lanka on February 13.

The JVP, or People’s Liberation Front, is Sri Lanka’s largest Marxist party and is currently the main governing party in the country at the head of an alliance of left and progressive forces.

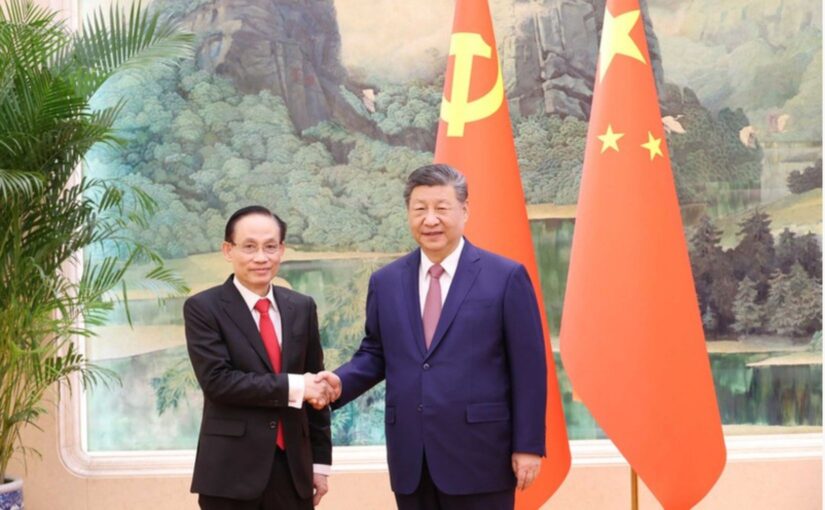

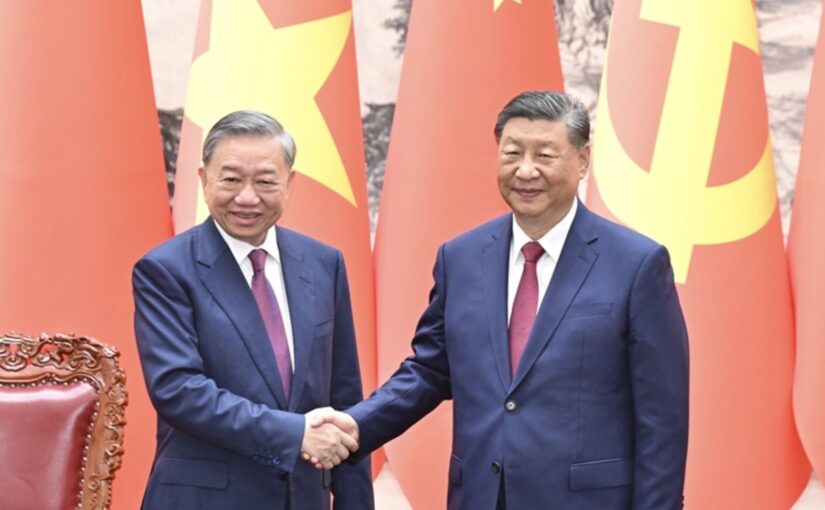

Liu said that in January 2025, President Xi Jinping met with President Anura Kumara Dissanayake who was visiting China. They reached important consensus on building a China-Sri Lanka community with a shared future and deepening exchanges of governance experience between the two countries’ ruling parties. The CPC, he continued, stands ready to continue strengthening exchanges at all levels with the JVP, conduct in-depth theoretical discussions and experience sharing on such topics as party building, major national development strategies and sustainable development, and to promote practical cooperation and friendship between the two peoples.

Silva and other leading JVP members said that during their visit to China last year, they witnessed firsthand how the CPC has led the Chinese people to achieve remarkable development accomplishments and won people’s wholehearted support. As Marxist governing parties, the two parties share common goals and ideals. Learning from the CPC’s experience in state governance and administration is of vital importance to the JVP. In particular, China’s practices in comprehensively exercising rigorous governance over the party and pursuing a people-centred development philosophy have provided valuable reference for Sri Lanka. The JVP appreciates China’s valuable support and assistance and is willing to further strengthen inter-party exchanges with the CPC and deepen cooperation in such areas as cadre training, digital city development, poverty reduction and promoting national unity, so as to better serve national development and improve the well-being of the two peoples.

The following article was originally published on the website of the IDCPC.

Beijing, February 13th—Liu Haixing, Minister of the International Department of the CPC Central Committee (IDCPC), held here today a video meeting with Tilvin Silva, General Secretary of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) of Sri Lanka.

Liu said, in January 2025, President Xi Jinping met with President Anura Kumara Dissanayake who was visiting China. They reached important consensus on building a China-Sri Lanka community with a shared future and deepening exchanges of governance experience between the two countries’ ruling parties. The two leaders also witnessed the signing of a memorandum of understanding on exchanges and cooperation between the two Parties. Over the past year, the CPC and the JVP have carried out diverse and fruitful exchanges and cooperation through inter-party channels to implement the important consensus reached by the two heads of state. The CPC stands ready to continue strengthening exchanges at all levels with the JVP, conduct in-depth theoretical discussions and experience sharing on such topics as Party building, major national development strategies and sustainable development, promote practical cooperation and friendship between the two peoples through the “political parties plus” platform, deepen multilateral coordination, and advance greater development of relations between the two countries and Parties.

Silva and others said, during the visit to China last year, we witnessed firsthand how the CPC has led the Chinese people to achieve remarkable development accomplishments and won people’s wholehearted support. As Marxist governing parties, the two Parties share common goals and ideals. Learning from the CPC’s experience in state governance and administration is of vital importance to the JVP. In particular, China’s practices in formulating medium- and long-term plans, comprehensively exercising rigorous governance over the Party, and pursuing a people-centered development philosophy have provided valuable reference for Sri Lanka. We appreciate China’s valuable support and assistance. The JVP is willing to further strengthen inter-party exchanges with the CPC and deepen cooperation in such areas as cadre training, digital city development, poverty reduction and promoting national unity, so as to better serve national development and improve the well-being of the two peoples. The Sri Lankan side also wishes the Chinese people a happy Spring Festival of the Year of the Horse.

Sun Haiyan, Vice-minister of the IDCPC; Qi Zhenhong, Chinese Ambassador to Sri Lanka; Bimal Rathnayake, Member of Political Bureau of the JVP, Head of the International Department, and Minister of Transport Highways and Urban Development, and Sunil Handunneththi, Member of the Political Bureau of the JVP and Minister of Industry and Entrepreneurship Development of Sri Lanka; and others were present.