The power of storytelling to sustain revolutionary enthusiasm and struggle is well-known. Stories both true and fictional have encouraged fighters in times both good and bad. Vladimir Lenin loved to read novels and took particular inspiration (and the title of one of his most famous works) from Chernyshevsky’s What is to be Done?. This novel continues to inspire, with Chinese President Xi Jinping citing it at the 2024 BRICS Conference, noting how the protagonist’s “unwavering determination and ardent struggle encapsulate exactly the kind of spiritual power we need today. The bigger the storms of our times are, the more we must stand firm at the forefront with unbending determination and pioneering courage.”

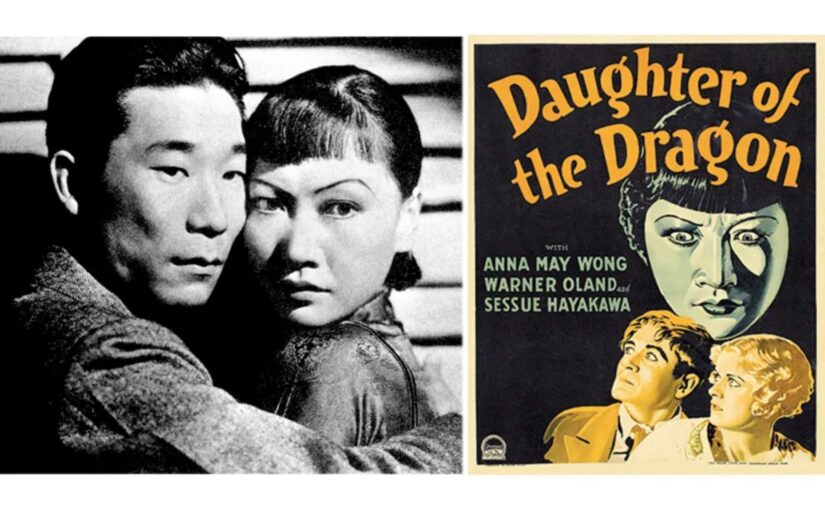

As the times have moved on, so have the formats of storytelling, and the moving image has come to replace the written word over the 20th century as the dominant form of narrative. In the same way as novels, the medium responds directly to the social contexts in which it is produced. In the Chinese revolutionary era, and the years leading up to the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, this was evident in the burgeoning film industry of the time, located mostly in Shanghai. The importance of many of these films and the extent to which they played an ideological role in sustaining the Chinese people’s resistance is charted in the below Sixth Tone article, which notes that the films “evolved from cultural commentary into a medium of resistance, help[ed] to shape public opinion and mobilize support for the war effort.” In place of some of the traditional melodramas or fantasy epics, the early Communist Party of China played a direct role in advocating stories which portrayed everyday people’s struggles, women’s struggles, and other tales that raised social awareness.

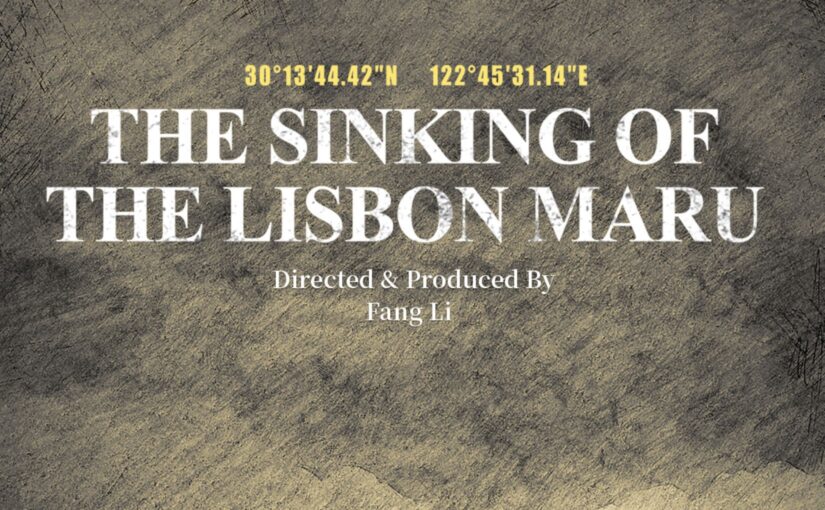

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Chinese people’s victory against Japanese Aggression, and their inestimable contribution to the victory in the World Anti-Fascist War, and once again cinema is making an important ideological contribution. 2025 has seen numerous films depicting this victory and the Chinese people’s experiences and contributions: Dead to Rights (a story in the context of the Nanjing Massacre), both fictional and documentary films covering the Dongji Island incident (where Chinese fisherfolk saved drowning British POWs), as well as the upcoming Evil Unbound, a story covering the notorious germ warfare human experiments carried out by the Japanese Imperial army.

In addition to re-establishing the proper historical contributions of the Chinese people in the history books, which for too long have been downplayed in the West, these narratives and documentaries also remind the Chinese people, and the peoples of the Global South at large, of the importance of protecting one’s own sovereignty and their capacity for resistance and victory.

Kim Jong Il noted in 1973 that “the task set before the cinema today is one of contributing to people’s development into true communists and assisting in the revolutionising and remodelling of the whole of society on the working-class pattern.” And whether you prefer the black and white classics, or the modern blockbusters, the leftist cinema of the People’s Republic of China continues to play this role.

The following article was first published by Sixth Tone.

In the years leading up to Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Chinese cinema had already begun preparing for it. Following the Mukden Incident in 1931, a false flag attack by Japanese troops on a railway line in northeastern China as pretense to invade Manchuria, Chinese filmmakers began incorporating themes of social crisis, injustice, and national survival into their work.

Continue reading The Revolutionary Reel: How Chinese cinema sustains the struggle