The following article, originally published in Sixth Tone, describes how, 75 years ago, the newly founded People’s Republic of China passed its first law — the 1950 Marriage Law — signalling the revolutionary state’s commitment to social transformation and gender equality. This law took priority because reforming marriage was seen as essential to dismantling feudal traditions that subordinated women and sustained patriarchal family structures. The new legislation enshrined freedom of marriage, monogamy, and gender equality, fundamentally redefining Chinese family life.

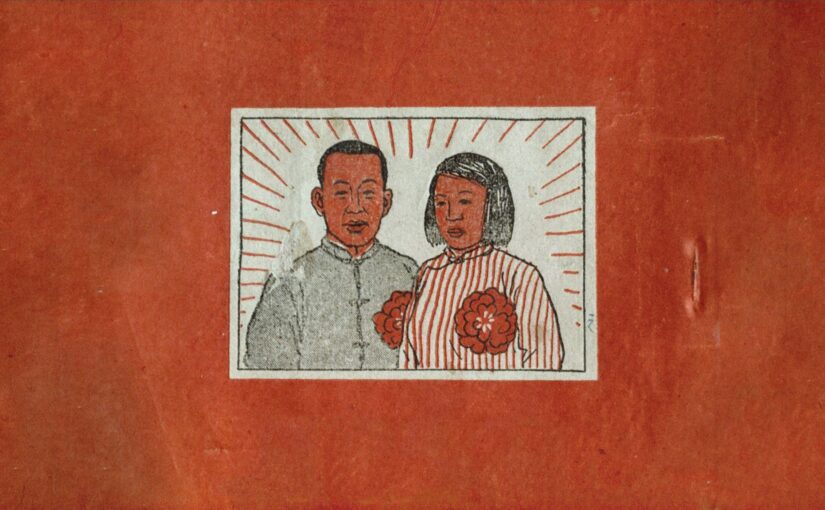

However, implementation of the law was predictably complicated. Deep-rooted conservative attitudes persisted, and early inspections revealed violent resistance to reform. Recognising the need for widespread education, the Communist Party launched China’s first national legal awareness campaign. Propaganda posters, songs, illustrated guides, and plays — including new versions of traditional stories like The Butterfly Lovers and Southeast Flies the Peacock — promoted the ideals of free marriage and women’s liberation in accessible, culturally resonant forms.

By 1953, the campaign reached its peak during the “Month of Promoting the Implementation of the Marriage Law,” with factories, schools, and workplaces across China holding lectures, exhibitions, and radio broadcasts.

Though the national campaign formally ended in 1953, its impact was enduring. The Marriage Law not only transformed Chinese social relations but also marked the beginning of a state-led effort to educate citizens in law and equality, embedding women’s rights in the foundations of the new China. While the road to equality and an end to discrimination is a long one, China continues to make impressive progress.

Seventy-five years ago, the People’s Republic of China issued its first law. It wasn’t the Constitution, nor was it the Civil Code — it was the Marriage Law.

This unique level of importance reflected the times. In revolutionary China, marriage reform was a major subject among early 20th-century intellectuals, who felt feudal concepts of family and marriage significantly stifled the individual freedoms of Chinese people — especially women — and hindered their participation in reshaping China. While choosing a partner to marry may be the status quo now, for centuries, families arranged marriages, divorce was rare, and women were subordinate to their husbands. As legal historian Qu Tongzu wrote in the book “Law and Society in Traditional China,” the main purpose of marriage in Imperial China was “to produce offspring to carry on ancestor worship” and was in no way concerned with the couple’s wishes.

Continue reading Inside the early push to revolutionise marriage in China