The following article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez – a slightly expanded version of an opinion piece written for the Global Times – discusses the controversies and difficulties setting up the loss and damage fund agreed at last year’s UN Climate Change Conference (COP27).

Noting that the fund is an application of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR), which principle lies at the core of international environmental law, the article points out that the rich countries have consistently failed to meet their clear legal and moral responsibility to provide the technology and finance to ensure the Global South can continue to develop, industrialise and modernise without causing significant environmental harm. The best-known example of this is the rich nations’ failure to meet their commitment, made in 2009, to channel $100 billion per year to developing countries to help them adapt to climate change and transition to clean energy systems.

The imperialist powers have developed the bad habit of blaming China for everything that goes wrong. In terms of environmental questions, Western politicians and journalists deflect criticism of their own slow progress on green energy by essentially assigning China culpability for the climate crisis. Carlos points out that, firstly, China is a developing country and thus has different responsibilities under the framework of CBDR; secondly, China has emerged as the pre-eminent force in renewable energy, electric transport, biodiversity protection, afforestation and pollution reduction. Furthermore it’s working with other countries of the Global South on their energy transitions.

The article concludes by calling on the wealthy countries to stop blaming China and to focus instead on meeting their own responsibilities.

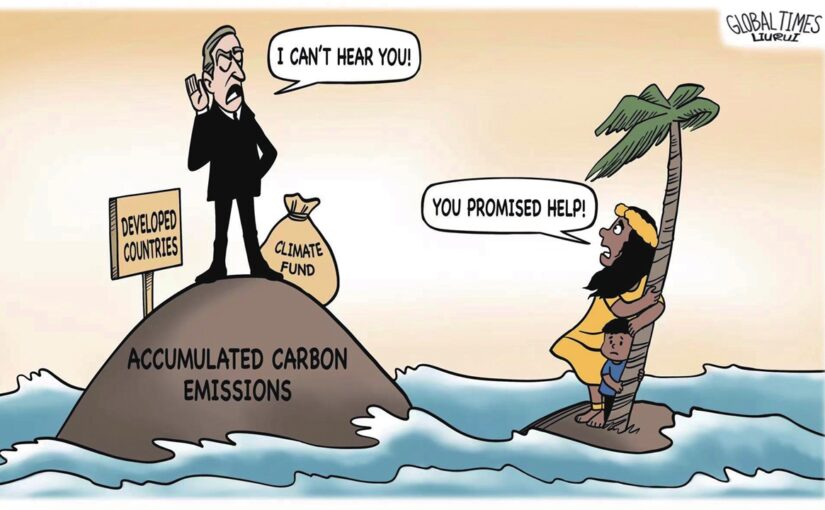

The most significant outcome of last year’s UN Climate Change Conference (COP27) was an agreement to set up a “loss and damage” fund to help climate-vulnerable countries pay for the damage caused by the escalating extreme weather events linked to climate change, such as wildfires, heatwaves, desertification, rising sea levels and crop failures. It is widely estimated that the level of funding needed for this purpose will be in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

Simon Stiell, UN Climate Change Executive Secretary, warmly applauded this agreement, for which the developing countries – including China – had fought long and hard. “We have determined a way forward on a decades-long conversation on funding for loss and damage – deliberating over how we address the impacts on communities whose lives and livelihoods have been ruined by the very worst impacts of climate change.”

The fund is an application of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR), agreed at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change of Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Under this principle, the developed countries have a duty to support developing countries in climate change adaptation and mitigation. All countries have a “common responsibility” to save the planet, but they vary in their historical culpability, level of development and availability of resources, and thus have “differentiated responsibilities”.

CBDR lies at the core of international environmental law, and is a key demand of those campaigning for climate justice. It recognises that development is a human right, and that the countries of North America, Europe, Japan and Australia fuelled their own development with coal and oil; they got rich while colonising the atmospheric commons. The US and Europe alone are responsible for just over half the world’s cumulative carbon dioxide emissions since 1850, although representing just 13 percent of the global population.

Therefore the primary moral, historical and legal responsibility is on the developed countries to provide the technology and the finance such that the Global South can continue to develop, industrialise and modernise without causing significant environmental harm.

Unfortunately, in the year since COP27, precious little progress has been made in terms of setting up the loss and damage fund. There have been numerous disagreements about which countries will contribute and which will benefit, and the US and other advanced countries have been firmly resisting the idea that contributions should be mandatory. Meanwhile the developing countries have had to accept the fund being hosted by the World Bank – which is seen as being essentially a policy instrument of the United States.

This is a familiar story. At the UN climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009, the rich nations pledged to channel 100 billion US dollars per year year to developing countries to help them adapt to climate change and transition to clean energy systems. Respected environmental journalist Jocelyn Timperley wrote that, “compared with the investment required to avoid dangerous levels of climate change, the 100 billion dollar pledge is minuscule”; and yet the promise has never been kept. The US spends upwards of 800 billion dollars a year on its military, but seems to be almost entirely unresponsive to the demands of the Global South for climate justice.

‘Blaming China’ has of course become the go-to option for Western politicians seeking to escape accountability and divert attention from their own failures. Various representatives from the wealthy countries have suggested that China – as the world’s second-largest economy and highest overall emitter of greenhouse gases – should contribute to the loss and damage fund in order for it to be fair and viable. Wopke Hoekstra, EU commissioner for climate action, recently commented: “I’m saying to China and others that have experienced significant economic growth and truly higher wealth than 30 years ago, that with this comes responsibility.”

The notion that China has the same duties as North America and Western Europe means turning the principle of CBDR on its head. China is a developing country, with a per-capita income a quarter of that of the US. It is still undergoing the process of modernisation and industrialisation.

Meanwhile, although it is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, its per capita carbon emissions are half those of the US, in spite of the US having exported the bulk of its emissions via industrial offshoring. Chinese emissions are certainly not caused by luxury consumption like in the West – average household energy consumption in the US and Canada is nine times higher than in China.

Furthermore, according to the World Food Programme, China is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world, with up to 200 million people exposed to the effects of droughts and floods.

From the very beginning of the international discussions around managing climate change, China has stood together with, and taken up the cause of, the developing countries. Indeed, China was one of the countries arguing vociferously for the loss and damage fund to be created.

China has nevertheless emerged as a global leader in the struggle against climate breakdown. According to an analysis by Carbon Brief, China’s carbon dioxide emissions are expected to peak next year, six years ahead of schedule. Given China’s extraordinary investment in renewable energy – its current renewable capacity is equivalent to around half the global total, and is rising fast – there’s every likelihood that it will reach its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 or sooner.

Meanwhile China is making a profound contribution to assisting other countries of the Global South with their energy transitions. Nigerian journalist Otiato Opali writes: “From the Sakai photovoltaic power station in the Central African Republic and the Garissa solar plant in Kenya, to the Aysha wind power project in Ethiopia and the Kafue Gorge hydroelectric station in Zambia, China has implemented hundreds of clean energy, green development projects in Africa, supporting the continent’s efforts to tackle climate change.”

While politicians and journalists in the West tend to ignore China’s successes in renewable energy, they loudly decry its construction of new coal plants. However, a recent Telegraph article provided an exception to this rule, noting that the approval of new coal plants “does not mean what many in the West think it means. China is adding one GW of coal power on average as backup for every six GW of new renewable power. The two go hand in hand.” That is, coal plants are being installed to compensate for the intermittency problems of renewable energy, and will therefore be idle for most of the time.

The US, Canada, Britain, the EU and Australia are all making insufficient progress on renewable energy, and are failing to meet their commitment to supporting energy transition in the Global South. By sanctioning Chinese solar materials and imposing tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, they are actively impeding global progress. Their proxy war against Russia in Ukraine has led to a dramatic expansion in the production and transport of fracked shale gas, at tremendous environmental cost.

These countries should stop pointing the finger at China and start taking their own responsibilities seriously. Let us hope we see some evidence of this at COP28.