This article by Li Xiaoyun, Chair Professor of Humanities at the China Agricultural University and a widely-respected expert in the field of poverty alleviation, makes a number of important and thought-provoking points about China’s successes in eradicating poverty.

Li makes the oft-overlooked point that China’s poverty alleviation efforts have been a long-term process starting not with the initiation of Reform and Opening Up in the late 1970s but with the land reform and social welfare measures of the 1950s. This is consistent with research showing that, around the world, “redistributive land reform, starting with breaking up land concentration and land monopolies, maximises economic efficiency and social justice and helps to alleviate rural poverty.”

By 1978, famine had been eradicated, feudal land ownership systems had been dismantled, and education and healthcare services were available throughout the country. This progress “provided an important basis for the high economic growth and massive poverty reduction that followed the reform and opening up.” Further, “the 1978 reform and opening-up policy effectively utilised the material and human resource base laid down in the area of agricultural development prior to 1978 and became the second interface of China’s poverty reduction mechanism.”

Rapid economic growth in the reform period, starting with the household responsibility system in the countryside, has been a crucial driver of poverty reduction in China. But Li also emphasises the importance of the government’s active role in this process, including through the provision of basic public services, the development of infrastructure, and the implementation of targeted poverty alleviation measures. He further notes that many countries of the Global South have experienced relatively high GDP growth but have not enjoyed similar levels of poverty reduction. This indicates that GDP growth alone does little to improve the lives of the poor, and that governments must devote substantial focus and resources to this project.

The author writes that although inequality has risen rapidly over the last four decades, the government has taken active and decisive measures to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are shared by all. “In order to address the issue of inequality, in 1986, the Chinese government formally established a leading agency for rural poverty alleviation at both the central level and at the local level. At the same time, special funds for poverty alleviation were set aside at the central financial level to designate poverty-stricken areas, thus beginning a targeted and planned rural poverty alleviation and development strategy.”

Tackling rural poverty has been a particular focus over the last two decades, starting with the complete abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006, the implementation of rural low income insurance in 2004 and the realisation of medical care coverage for all rural residents by 2010. With the start of the targeted poverty alleviation campaign in 2014, “resources are pooled through extraordinary administrative initiatives, concentrating human, material and financial resources on the poorest areas and neediest groups.”

Li observes that China’s urbanisation has also made an important contribution to poverty reduction – “the movement of the rural population into industry and cities means an increase in income and welfare, and thus industrialisation and urbanisation have a direct poverty-reducing effect.” Meanwhile “the significant decline in the rural population has also meant a relative increase in the labour productivity of those who remained in the countryside and continue to work in agriculture.” It’s worth noting that in several other countries, rapid urbanisation has taken place in a relatively disorganised manner, with peasants escaping a life of grinding poverty and debt in the countryside, only to end up in peri-urban slums without secure employment or access to services. China’s urbanisation, while not without challenges and problems, has been generally well-managed.

The article concludes with a hugely important point about the indispensable role of the Communist Party of China in the fight against poverty:

The main reason why China was able to finally eradicate absolute rural poverty was because the CPC relied on its political advantage of unifying society and strongly integrated its political commitment to poverty reduction across all sectors of government and society, breaking the constraints of interest groups and administrative bureaucracy and achieving a redistribution of wealth and opportunities.

Which is to say that a socialist system provides the best possible framework for improving people’s lives.

This article first appeared on Progressive International.

On 25 February 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping officially declared in Beijing that China will finally eliminate absolute rural poverty. As the standard for absolute rural poverty in China is higher than the World Bank’s standard for extreme poverty,2 China lags behind the World Bank’s estimates for eliminating absolute rural poverty. According to the World Bank’s poverty line of US$1.9 per person per day, there were 878 million poor people in China in 1981, and the incidence of poverty was 88.3%. By 2015, that number had fallen to 9.7 million, with an incidence of 0.7%.3

Economic growth and income redistribution are generally accepted as two important drivers of poverty reduction. Based on the situation in the United States, in 1964 Anderson suggested that economic growth was an important contributor to poverty reduction in the country.4 However, the experience of developing countries has been different. States in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, have, to varying degrees, seen relatively high levels of economic growth over the past two decades, but they have not achieved significant poverty reduction. This shows that economic growth is only one factor in poverty reduction. For poverty reduction to succeed, economic growth must also be set to address poverty alleviation.5 Secondly, the rise in income inequality accompanying economic growth is a major problem for developing countries and many middle-income countries. The rise in inequality directly worsens relative poverty, a process that China began to experience at the turn of the century. In the context of poverty reduction, China’s primary challenge before the new century was to put economic growth in the service of the poor. Since then, inequality became increasingly pronounced. These two features have greatly influenced changes in China’s poverty reduction strategies and policies.

Views on poverty reduction in China tend to fall into two categories. One sees China’s development and poverty reduction as part of a universal trend of socio-economic transformation that followed as a result of China’s assimilation into globalisation. The other sees China’s achievement of development and poverty reduction as a particular case, with its own unique Chinese characteristics.6 This paper will mainly introduce and analyse the process of poverty reduction in China from three aspects – the historical role of development in poverty reduction before 1978, economic growth in service of poverty alleviation after 1978, and the goal of poverty eradication in the face of increasing inequality – at the same time considering its core elements and their global significance.

I. Understanding the role of development for poverty reduction before 1978

Before 1978, China’s development had three effects on poverty. First, it alleviated hunger-based poverty; second, it alleviated multidimensional poverty, for example in education, health, infrastructure and gender; and third, it provided an important human and material base for further economic growth. China did not focus directly on the incomes of poor groups for a long time after the 1950s, and individual welfare improvements were slow, with national social-development goals mainly reflected in inclusive social services.7 It is worth noting that a large number of studies on poverty in China tend to ignore the relationship between development and poverty reduction before the reform and opening up of the economy. In fact, poverty simply reflects broader socio-economic conditions; neither increases nor decreases in poverty happen suddenly. In China, large-scale poverty reduction is a historical process.8

In the early 1950s, life expectancy in China was 35, compared to 68 and 63.68 in the United States and Europe respectively during the same period. In 1952, the country’s population was 575 million and total grain production was 163.92 million tonnes, with a per capita grain holding of only 285 kg. In 1950, before the Chinese government embarked on its programme of land reform, 54.8% of China’s arable land was concentrated in the hands of 14.5% farmers. Peasants, who accounted for 85.5% of China’s farmers, held less than 50% of arable land. The inequitable distribution of rural land is considered to be one of the main reasons for China’s long-term poverty.9 Following land reform, 92.1% of poor and middle-income peasants had their own land. Between 1949 and 1957, China’s grain production increased from 113.18 million tonnes to 195.05 million tonnes, and grain yields increased from 1035 kg/ha to 1463 kg/ha.10 Land systems have always been a focus of poverty research, and in general, Keith Griffin et al. suggest that redistributive land reform, starting with breaking up land concentration and land monopolies, maximises economic efficiency and social justice and helps to alleviate rural poverty.11 An analysis of countries’ experiences with different types of redistributive land reforms argues that “redistributive reforms represented by land reform, along with state facilitation and support, will contribute to real benefits for the poor”.7 12 Many developing countries, such as the Philippines, have had great difficulty in alleviating poverty due to high inequities in the land system. Practice has shown that countries that have completed land reform in one form or another have achieved significant poverty reduction, with land reform in Japan, South Korea and the region of Taiwan, which began in the 1950s, all playing a positive role in poverty alleviation and the eventual elimination of absolute poverty.13 Land reform in China in the 1950s had a direct effect on poverty reduction and can be seen as an important policy for institutional poverty reduction. At the same time, changes in the land system provided a social basis for equity.

Poverty eradication was the primary objective of China’s path of modernisation, adopted after the 1950s. Under this strategy, China began implementing broad changes to the structure of the national economy, starting with education, health care, science and technology, and infrastructure. China’s illiteracy rate fell from 80% in 1949 to 22% in 1978.14 Its irrigated farmland increased from 19.959 million hectares in 1952 to 45.003 million hectares in 1978, and the amount of fertiliser used across the country increased from 78,000 tonnes in 1952 to 8.84 million tonnes in 1978. China’s per capita grain holdings exceeded 300 kg by 1978, a significant improvement even though the FAO standard of 400 kg per capita — a measure of food security — was not attained.7

In fact, farmers’ enthusiasm for production stimulated by the rural reform was grounded largely in the country’s long-term investments in agricultural infrastructure — including in irrigation, agricultural machinery, fertiliser and especially agricultural science and technology — before the reform and opening up. 45% of the country’s arable land was irrigated in 1978, and that percentage has not increased significantly since the reform and opening up.

Another important factor in China’s development and poverty reduction before 1978 was the relatively equitable starting point. Around the year 1978, the national Gini coefficient was 0.318,15 and the Gini coefficient in rural China was around 0.212,16 which shows the equity of income distribution in Chinese society at that time. There is a complex relationship between the pattern of income distribution and economic growth. Generally speaking, income disparity is considered to affect economic growth in four ways. One view holds that equal income distribution better promotes the division of labour among different levels of skill holders, thus promoting economic growth.17 A second view, based on the assumption of imperfection in credit markets, argues that income inequality affects growth by influencing occupational choices, with poorer groups finding it difficult to access occupations that require high levels of investment.18 A third view takes a political economy perspective, arguing that income disparities are redistributed through government taxation and fiscal spending, which has an impact on economic growth.19 Finally, a fourth view says that, from the perspective of consumer demand, demand is the main driver of economic growth and that inequality in income distribution reduces consumer demand and thus constrains economic growth.20 Thus, although China’s pre-1978 policies suffered from economic inefficiencies, the relatively equitable social distribution that resulted from them provided an important basis for the high economic growth and massive poverty reduction that followed the reform and opening up. Reconciling income distribution and poverty reduction is a major issue for many developing countries as they enter into social transition, and for many countries in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, one of the major problems in reducing poverty is the high incidence of poverty, but also the high inequality in income distribution. The incidence of poverty in sub-Saharan African countries under the US$1.9 international poverty line has only slowly declined from 54.9% in 1990 to 42.3% in 2015,21 with such countries still facing significant pressure to reduce poverty. During the same period, the Gini coefficient in sub-Saharan African countries hovered at a high level — between 0.4% and 0.5%. The inequality of income distribution greatly affected the effectiveness of poverty reduction, and its income distribution inequality was only better than that of Latin America.22

II. Pro-poor economic growth

China’s pro-poor economic growth was primarily grounded in the agricultural development, industrialisation and urbanisation that it experienced since the reform and opening up. Since that time, China has developed different mechanisms for poverty reduction at different stages of its history, and there is an organic relationship between these mechanisms, which together form a continuous and sustainable system of poverty reduction tools.

The alleviation of non-income-based poverty before 1978, the construction of infrastructure, and the conditions of social equity all formed an important basis for China’s high economic growth after 1978, and it was the same basis that provided for the poor to benefit relatively fairly from the economic growth and get rid of poverty.

China’s post-1978 economic reforms began in the countryside. The introduction of the contract responsibility system unleashed farmers’ enthusiasm for production. 1978-1985 saw China’s agriculture enter a phase of extraordinary development, driven by the reform of the rural economy. At this time, the average annual growth rate of China’s agricultural GDP was 6.9%.23 At the same time, the annual per capita income of Chinese farmers also grew at unprecedented rates. From Table 1, we can see that from 1978-1984, the annual per capita income growth rate for Chinese farmers was 16.2%. From 1978-1984, China’s agricultural growth and farmers’ income growth remained relatively high compared to other periods.24

In terms of the characteristics of the economic and social structure, for a long time after 1978, China’s population was mostly rural, with only 17.9% of the Chinese population living in cities in 1978. Farmers’ incomes were dominated by agricultural operations. Agriculture made up more than 35% of China’s national GDP. In terms of the development of agriculture, the extraordinary growth of agriculture in the early years of reform and opening up was mainly reflected in two aspects. First, the rapid development of crop farming associated with grain production. China’s total grain production grew from 304.77 million tonnes to 379.11 million tonnes between 1978 and 1985, and per capita grain availability increased from 317kg to 358kg. China officially crossed the 300 kg per capita threshold after 1978. The second is the rapid growth of the breeding industry. Crop farming and breeding were the main occupations of small farmers in China and the main source of livelihood for their families. Economic growth in post-1978 China, which began with agricultural development, was vital to poverty reduction. In fact, Martin Ravallion and Chen Shaohua hold that economic growth in the agricultural sector has been the main contributor in increasing the income of the poor. The impact of economic growth in the agricultural sector on the livelihood of the poor is four times that of the industrial or service sector.25 The 1978 reform and opening-up policy effectively utilised the material and human resource base laid down in the area of agricultural development prior to 1978 and became the second interface of China’s poverty reduction mechanism. The relationship between agricultural development and poverty reduction does not always depend on the growth of agriculture or the size of the agricultural population. The effective ability of agricultural development to reduce poverty also depends on population growth, which has been maintained at less than 2% since 1978. The high net growth rate in agriculture has two direct effects, one leading to an increase in output per capita and the other generating a surplus. Many South Asian countries and sub-Saharan African countries have been able to achieve relatively good agricultural development performance following structural adjustment. Although these countries have not been able to sustain agricultural growth rates as high as China’s over a longer period of time, sub-Saharan African countries have largely maintained agricultural growth rates of between 3.5 and 4% over the last decade or so, a rate that is actually quite similar to China’s conventional agricultural growth rate. The difference is that the population growth rates in these countries are higher, in some cases reaching 3%. This is why the net agricultural growth rate is comparatively low, which partly explains the failure of agricultural growth to effectively alleviate poverty in these countries.26

After 1986, China’s agriculture moved from supernormal growth to regular growth, and the growth of farmers’ incomes began to slow down. The role of the poverty reduction mechanism created by the extraordinary growth in farmers’ incomes, which in itself was driven by the extraordinary growth in agriculture, began to decline. After 1986, China’s economic and social development took a new turn. The surplus capital from agriculture, driven by the rapid development of agriculture in the previous period, was rapidly transferred to township and village enterprises (TVEs) which were once mainly in the form of commune and brigade enterprises (CBEs).1 The rural industry then swiftly absorbed the surplus and raw materials, as well as the labour force from agriculture, which constituted a new driving force for China’s poverty reduction. After 1986, peasant non-farm incomes increased year by year, and after the late 1980s, a bottleneck in the development of TVEs emerged and their contribution to peasant incomes began to suffer. On this basis, China began to attract foreign investment on a large scale and created a number of labor-intensive industrialization bases mainly in developed and coastal areas, which induced the large-scale cross-regional flow of Chinese rural labor force. From the late 1990s to the beginning of the century, there were approximately 121 million migrant workers in China each year, and as of 2012, Chinese farmers’ income reached 3,447.46 RMB, accounting for 43.5% of farmers’ per capita net income of 6,977.4 RMB. Driven by industrialisation, the pace of urbanisation in China has also gradually accelerated. China’s urbanisation grew from 17.9% in 1978 to 60.6% in 2019, with nearly 300 million of China’s rural population permanently leaving the countryside. Industrialisation and urbanisation have two effects on poverty reduction, the first being that industry is a highly rewarding sector and cities are spaces of high welfare. The movement of the rural population into industry and cities means an increase in income and welfare, and thus industrialisation and urbanisation have a direct poverty-reducing effect. Without industrialisation and urbanisation, poverty reduction in China is likely to have remained at the level of poverty reduction brought about by the supernormal growth of agriculture, and is unlikely to have produced the massive poverty reduction achieved so far. The second aspect is that the significant decline in the rural population has also meant a relative increase in the labour productivity of those who remained in the countryside and continue to work in agriculture. The TVEs and rural industrialisation have organically linked China’s agricultural development to industrialisation and urbanisation, giving China’s development model a very clear endogenous development character. That is, the growth of the Chinese economy has always been centered around the basic structure of the Chinese economy, while at the same time the mechanisms of poverty reduction in China have been organically aligned with its economic structure and the social transformation of the Chinese economy. The process from agricultural development to urbanisation has always been closely linked to an increase in income and improvement of welfare for farmers, which constitutes a pattern of pro-poor economic growth in China. There is much research by scholars, both domestic and foreign, on the contribution of agricultural development, industrialisation and urbanisation to poverty reduction in China. The main conclusions are relatively consistent, with some pointing out that the driving factors behind China’s massive poverty reduction in the 40 years of reform and opening up were multiple, but the most important was the result of the combined thrust of high economic growth and poverty alleviation and development, which not only made an outstanding contribution to the global anti-poverty cause, but also provided lessons for other countries to learn from;27 there are also arguments that during the 1980s and 1990s, there was skepticism about the sustainability of China’s economic growth and poverty reduction, and the role of economic growth indeed begun to decline in the twenty-first century. However, with the promotion of an inclusive social security system, China’s development has gradually developed into an inclusive development model, from a relatively pro-poor model in the past. This development experience started to be taken seriously in the international arena, and a large number of developing countries have begun to learn from China’s development and poverty reduction experience;28 There is also a lot of discussion and advocacy surrounding the “Chinese model”, with some studies arguing that for many Third World developing countries, the adoption of the Western model has not resulted in socio-economic development and stable functioning of democracy, and that the significance of the Chinese model lies in whether it can be an alternative model to other modernisation models.29 There is also a view in the international academic arena that the uniqueness of China’s development path has become a source of ideas and new development aid that is different from other existing experiences in the post-colonial period.30

The pro-poor mechanisms of China’s economic and social transformation in different periods are very important references for poverty reduction in developing countries. Any developing country wishing to achieve sustainable poverty reduction needs to establish linkages conducive to poverty reduction in all the different stages of economic and social transformation, so that there is no decoupling of economic development from poverty reduction. Sub-Saharan Africa has maintained relatively high economic growth rates over the past decade or so, with GDP growth at 5.575% in 2010 and an average GDP growth of 3.32% from 2010 to 2018, despite falling back to a decade low of 1.6% in 2016 due to the global economic downturn.31 However, the rate of decline in the incidence of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa over the same period has not been satisfactory. An important problem with economic development and poverty reduction in these countries is that there is a decoupling between the structure of economic growth and poverty reduction.32 For example, in many African countries, the fastest growing sectors over the last decade or so have been transport, communications and mining, which are largely concentrated in technology intensive and capital intensive industries. At the heart of the disconnect between economic growth and poverty reduction is the failure to root economic growth in the underlying socio-economic characteristics of these countries, not only from the perspective of economic growth, but also from the perspective of agricultural development. Agricultural growth in most sub-Saharan African countries over the last decade or so has been driven by an expansion in acreage rather than an increase in yields per unit of land area, meaning that agricultural growth has not been based on productivity growth. Having experienced a golden period of agricultural development following structural adjustment in many African countries, the last decade has seen a rush to place agricultural development high on the national development and poverty reduction agenda. However, in many countries, agricultural development has not been complemented by industrialisation, and therefore its performance in reducing poverty has not been further enhanced or sustainable. Paul Collier’s research on African development argues that while agriculture is important for development and poverty reduction in Africa, without the pull of urbanisation, it will be very difficult to achieve economic and social transformation and poverty reduction in Africa.33 Over the past decade or so, countries in Southeast Asia have been undergoing rapid socio-economic transformation and these countries have also achieved varying degrees of poverty reduction. Based on the international poverty line of US$1.25 per person per day, the incidence of poverty in ASEAN countries plummeted from 47% to 14% between 1990 and 2015.34 At the same time, however, it needs to be seen that economic growth and social transformation in Southeast Asian countries has been driven mainly by external investment rather than benefiting from the surplus of their own agricultural development. From the perspective of capital supply, the performance of the socio-economic transformation and poverty reduction that is unfolding in South-East Asia is highly volatile.

III. Addressing inequality-based poverty reduction practices

Numerous studies by development agencies, including the World Bank, and development economists Fosu and Ravallion have shown that persistently widening inequality affects the translation of economic growth into poverty reduction and, in turn, has the effect of eroding poverty reduction gains.35 Ravallion et al. found that while economic development helped to alleviate poverty, the widening gap between rich and poor had the most significant effect on worsening poverty.36 Many Chinese scholars have pointed out that the widening income gap between urban and rural areas and within rural areas in China has reduced the access of the poor to income opportunities and their share of benefits, which is not conducive to the alleviation of rural poverty.37 China has likewise experienced a rise in inequality during its rapid economic growth and social transformation over the past four decades. China’s Gini coefficient rose from 0.288% in 1981 to 0.465% in 2016, making China one of the countries with the largest differences in income distribution in the world. As inequality continues to rise, the pro-poor character of economic development will gradually diminish.

In fact, in the mid-1980s the Chinese government had begun to recognise the multifaceted impact of economic growth on income distribution and regional development. As China’s strategy for economic development since its reform and opening up has been to encourage some people and some regions to get richer first, it is tantamount to saying that the government’s development-oriented policies themselves support the widening of disparities. Therefore, in order to address the issue of inequality, in 1986, the Chinese government formally established a leading agency for rural poverty alleviation at both the central level and at the local level. At the same time, special funds for poverty alleviation were set aside at the central financial level to designate poverty-stricken areas, thus beginning a targeted and planned rural poverty alleviation and development strategy. China’s rural poverty alleviation and development strategy is first and foremost a poverty reduction policy with the aim of complementing and correcting the shortcomings of the development policies of regional and group priorities. For example, with the support of the reform and opening-up policy, the coastal and developed regions have taken advantage of the reform and opening-up policy on a priority basis, and these regions have developed rapidly. At the same time, many marginal and backward regions, which do not have the comparative advantage of regional economic development, have seen the gap between them grow wider. China’s Rural Poverty Reduction and Development Programme targeted these backward regions through the designation of poverty-stricken counties, while providing corresponding support policies. At the end of the last century, both international and Chinese experts conducted systematic studies on the performance of China’s rural poverty alleviation and development. In 1990, the World Bank collaborated with the Chinese government to produce the study “China: Strategies for reducing poverty in the 1990s”, and in 2001, the World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme launched the study “China: Overcoming Rural Poverty”, following a comprehensive and systematic study of China’s poverty reduction efforts. These reports concluded that “China is widely recognized for its achievements in reducing absolute poverty since the adoption of a broad program of rural economic reforms beginning in 1978.” And that China’s “scale and funding of its poverty reduction program, and the sustained dramatic reduction of absolute poverty over the last twenty years of reform, are exemplary by any standards.”38 Domestic scholars argue that since the implementation of planned rural poverty alleviation and development, economic development in poor areas has increased significantly and the incomes of farmers in poor areas have continued to rise.39

Since the turn of the century, China’s economic and social structure has started to undergo a major transformation. This is mainly reflected in the increasing rate of urbanisation, the widening of inequality year by year, and the weakening of the pro-poor character of the economic structure year by year. Under these conditions, China’s urban-rural relationship is also beginning to change, and elements of supporting agriculture are beginning to appear in China’s development policies. The complete abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006 marked the beginning of a change from the days when agriculture was a raw material and capital provider for industrialisation. The implementation of rural low income insurance in 2004 and the gradual realisation of basic rural cooperative medical care coverage for all rural residents by 2010 marked the beginning of a shift in China’s poverty reduction policy from one that was primarily focused on economic development to one that requires a dual mechanism for poverty reduction, which is still centred on economic development and at the same time requires the introduction of a distribution mechanism for safeguards. China’s lack of social protection has been the focus of academic and social criticism and concern.. However, in terms of the effectiveness of poverty reduction, only when the marginal benefit of the developmental poverty reduction is diminishing, can the guaranteed social security poverty reduction mechanism really play an effective role. This is both an important mechanism in China’s response to how to advance poverty reduction in the face of growing inequality, and an integral part of the sustainability of poverty reduction in China. The combination of developmental and guaranteed social security poverty reduction based on economic growth is the most prominent feature of China’s poverty reduction mechanism. Ensuring that those who cannot benefit from economic competition do so through guaranteed social security poverty alleviation, while supporting those who can afford it to escape poverty through targeting mechanisms to compete in the market, is fundamental to China’s poverty reduction achievements.

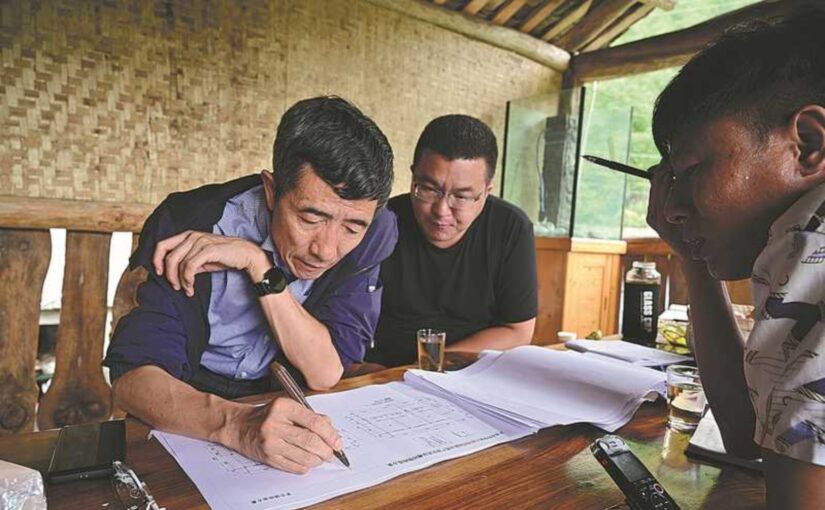

The greatest obstacle to poverty eradication in a context of increasing inequality is the entrenchment of interest groups and a weakening of the pro-poor character of the economic structure itself, which results in economic growth and social structures that are exclusionary to the poor. Since 2014, the Chinese government has upgraded precise poverty alleviation to a poverty eradication campaign. The meaning of the war on poverty is that through the political authority of the Communist Party of China (CPC) to lead society and through the strengthening of government leadership, resources are pooled through extraordinary administrative initiatives, concentrating human, material and financial resources on the poorest areas and neediest groups. The Chinese government has invested an unprecedented RMB 1.6 trillion in the fight against poverty over the past eight years. Measured against the new poverty line set by the Chinese government in 2011, the incidence of poverty in China has fallen from 10.2% in 2012 to 0.6% in 2019.42

IV. Conclusion and Discussion

Poverty reduction in China was a major event in the history of global development in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. How China’s experience of poverty reduction is presented objectively and historically is important not only for how the process itself is understood, but also for development for other developing countries.

Firstly, China’s poverty reduction is the result of a specific historical process of political, economic and social change in the country. The infrastructure that China created through massive labour inputs prior to 1978 played a huge role in the subsequent development of agriculture. And the infrastructure inputs were achieved at an extremely low cost, unlike the debt burden created by many African countries’ reliance on aid money for infrastructure development. That is why Chinese officials tend to emphasise self-reliance when presenting China’s development experience. The equitable social distribution pattern that existed in China before the reform and opening up was in fact an important basis for the rapid economic growth and massive poverty reduction that was possible after China’s reform and opening up.

Second, the foundation for large-scale poverty reduction in China is long-term economic growth, which itself needs to bring about meaningful social transformation. And this process needs to have mechanisms that are conducive to the gains of the poor. Since both large-scale poverty reduction and the eradication of absolute poverty take a long time, poverty reduction mechanisms need to have pro-poor continuity in terms of the mechanisms of economic growth.

Finally, in a context of increasing inequality, the eventual eradication of absolute poverty requires strong political commitment and a strong governmental role. China’s poverty reduction practices since the turn of the century, particularly since 2012, have highlighted the role of the Communist Party and the government. In conditions of increasing inequality and decreasing social mobility, poverty is easily structuralised, and the poverty trap cannot be broken through a general governmental role alone. The experiences of Europe and the United States are the two more prominent extremes in this regard. Europe, with its long tradition of socialism and the repeated rule of socialist parties, has seen the evolution of capitalism in which many pro-poor policies have gradually become law, thanks to the alternating rule of the pro-labour or democratic socialist parties and the widespread influence of socialist thinking, as well as the impetus of the workers’ movement, resulting in a welfare-based system. The US, in contrast, has struggled to make breakthroughs in policy areas with general poverty reduction implications, with its emphasis on individuals working to improve their livelihoods in the market and securing their own welfare primarily through personal income in market mechanisms, such as investing personal income in commercial mechanisms for education, healthcare and pension insurance to ensure the maintenance or improvement of their future welfare. Although the US government has poverty alleviation programmes, particularly social charity assistance, in general, poverty governance in the US does not rely on income transfers.40 The main reason why China was able to finally eradicate absolute rural poverty was because the Communist Party of China relied on its political advantage of unifying society and strongly integrated its political commitment to poverty reduction across all sectors of government and society, breaking the constraints of interest groups and administrative bureaucracy and achieving a redistribution of wealth and opportunities.7

References

- Translators’ note: See ‘The Changing Face of Rural Enterprises’ Source

- Wang Pingping, Fang Huliu, Li Xingping. Comparison of China’s poverty standards and international poverty standards. China’s rural economy, 2006(12):62-68.

- World Bank Database Source

- W. H. Locke Anderson, Trickling Down: The Relationship Between Economic Growth and the Extent of Poverty Among American Families, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol 78(4), 1964, pp. 511–524.

- Asian Development Bank (ADB), 1999. Fighting Poverty in Asia and the Pacific: The Poverty Reduction Strategy of the Asian Development Bank. Manila, Philippines.

- Li Xiaoyun, Wu Yifan, Wu Jin. Targeted poverty alleviation: China’s new practice of state governance. Journal of Huazhong Agricultural University (Social Science Edition), 2019(05):12-20+164.

- Li Xiaoyun, Li Lanlan. China’s Poverty Alleviation from the Perspective of International Poverty Reduction: Relevant Experiences in Poverty Governance. Foreign Social Science, 2020(06):46-56.

- Li Xiaoyun, Yu Lerong, Tang Lixia. The anti-poverty process and poverty reduction mechanism in the 70 years following the founding of New China. China’s rural economy, 2019(10):2-18.

- Guo Dehong. Research on Farmers’ Land Issues in Modern China. Qingdao Publishing House, 1993, pages 187-188.

- Planning Department of the Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. China Rural Economic Statistics (1949-1986). Agriculture Press, 1989: 78-79.

- Griffin K, Azizur Rahman Khan, Ickowitz A. Poverty and the Distribution of Land, Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 2, 2002, pp. 291-292.

- Putzel J., Land Reforms in Asia: Lessons from the past for the 21st century, DESTIN Working Papers, Vol. 4, 2000.

- Zhang Guilin. Reform of East Asian Farmland System. China’s Rural Economy, 1994(09):61-64.

- National Statistical Bureau: “National Annual Statistical Bulletin 1979”, website of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China Source

- United Nations Program and Development Agency Representative Office in China. China Human Development Report 2016. Chinese Translation Publishing House, 2016: 27.

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2001 China Rural Household Survey Yearbook. China Statistics Press, 2001:3.

- A. Fishman and A. Simhon, The division of Labor, Inequality and Growth, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 7, 2002, pp.117—136.

- Abhijit V. Banerjee and Andrew F. Newm. Occupational Choice and the Process of Development, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 101(2), 1993, pp. 274-298.

- Torsten Persson and Guido Tabellini, Is Inequality Harmful for Growth, American Economic Review, Vol. 84, 1994, pp.149—187.

- Kevin M. Murphy, Andrei Shleifer, Robert Vishny. Income Distribution, Market Size, and Industrialization, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 104, 1989, pp.537-564.

- UNDP, Human Development Report 2019/2008/2000

- United Nations, Income inequality trends: the choice of indicators matters, No. 8, Social Development Brief, 2019.

- Huang Jikun. Forty years of China’s agricultural development and reforms and future policy choices. Agricultural Technology and Economy, 2018(03):4-15.

- Huang Jikun. Institutional changes and sustainable development: 30 years of Chinese agriculture and rural areas. Gezhi Publishing House, Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2008:4.

- Ravallion M., Are There Lessons for Africa from China’s Success Against Poverty?, World Development,Vol. 2, 2009, pp. 303-313.

- Li Xiaoyun, Tang Lixia, Xu Xiuli, Qi Gubo and Wang Haimin. What can Africa Learn from China’s Experience in Agricultural Development? IDS Bulletin, 2013, 44 (4):31-41.

- Wang Sangui. Overcoming poverty in development – a summary and evaluation of China’s 30 years of experience in large-scale poverty reduction. Management World, 2008(11): 78-88.

- Lin Yifu. Interpretation of Chinese Economy. Peking University Press, 2012:5-7.

- Zheng Yongnian. The Chinese Model in the International Development Pattern. Chinese Social Sciences, 2009(5): 20-28.

- Large D. Beyond, Dragon in the Bush: The Study of China - Africa Relations, African Affairs, Vol 426, 2008, pp. 5-61.

- World Bank, World Bank Database Source

- Li Xiaoyun, What can Africa learn from China’s agricultural miracle?, in OECD, Development Co-operation Report 2013: Ending Poverty, OECD Publishing, 2013:87-94.

- Collier, Paul and Dercon, Stefan, “African Agriculture in 50Years: Smallholders in a Rapidly Changing World?”, World Development, vol.63(C), 2014. pp. 92-101.

- ASEAN Secretariat, ASEAN Statistical Report on Millennium Development Goals 2017, p. 22 Source

- Ravallion, M., Can high inequality developing countries escape absolute poverty? Economics Letters, vol. 56, 1997. pp. 51-57.

- Ravallion M. and Chen S., “Measuring Pro-poor Growth”, Economics Letters, vol. 78, No. 1, 2003, pp. 93-99.

- Hu Angang, Hu Linlin, Chang Zhixiao. China’s Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction (1978-2004). Journal of Tsinghua University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 2006(05): 105-115.

- World Bank: “Country Report: China Overcomes Rural Poverty”, China Financial and Economic Publishing, 2001.

- Wang Sangui. China’s 40 years of large-scale poverty reduction: driving forces and institutional foundations. Journal of Renmin University of China, 2018, 32(06):1-11.

- M.R. Rank, One nation,underprivileged: Why American Poverty Affects Us All[M]. Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, pp. 10-16.

- Li Xiaoyun, Yang Chengxue. Poverty Alleviation: Alternative Revolutionary Practice in the Post-revolutionary Era. Cultural Aspects, 2020(03): 89-97+143.

- National Bureau of Statistics, China Rural Poverty Monitoring Report 2019

I am from Vancouver,Canada and i wanted to say that when i was young in the 1960s Poverty in Canada was felt every where in Canada. Now in 2024 it is even worse than it was back then. This shows that Poverty under Capitalist Gov’ts increases over the years it don’t decrease.

China got prove that it eliminates poverty and Canada got prove that it along with other Capitalist Countries don’t eliminate Poverty.

Today Western Countries are more interested in keeping the wars going in Ukraine and Palestine than they are in reducing Poverty. People all over the world are demonstrating against this insane Policy of Western Gov’ts every week of the year. People today because of what is happening in Palestine and Ukraine got a lot more Political Conscience than they had before.