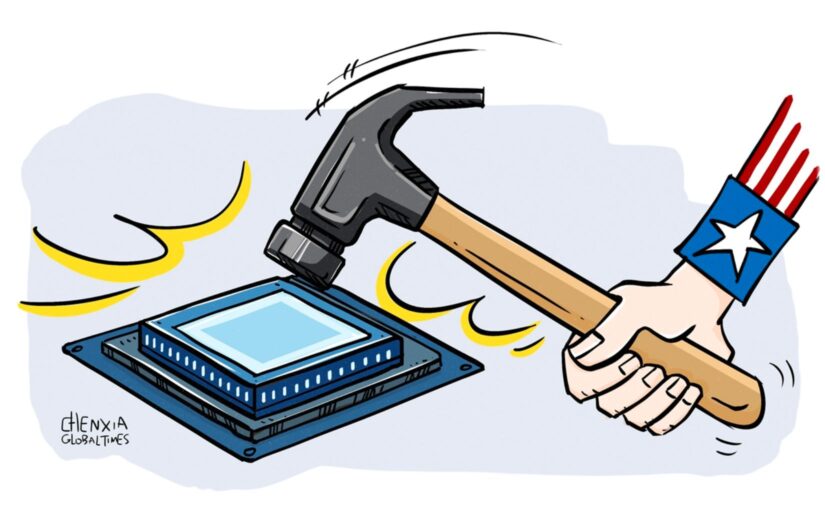

The following article by Bappa Sinha, originally published in People’s Democracy (the English-language weekly newspaper of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)) provides valuable insight into the US-initiated “chip wars” against China, which “show no signs of abating and have escalated further in 2023 with indications of more to come.”

Sinha describes the rationale for the chip wars as being essentially economic, with the US seeking to maintain its technological dominance. “Having already lost its manufacturing leadership due to outsourcing production, the US is critically dependent on its lead in advanced technologies to retain its global dominance. With China catching up and, in many cases, leapfrogging the US in frontier technologies, the US sees the denial of semiconductor technologies with its outsized impact on modern production and economy as an effective mechanism of keeping China down.”

The author details the numerous measures that have been taken by both the Trump and Biden administrations to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductor technologies, including the imposition of export controls, the blacklisting of Chinese companies, and the imposition of sanctions.

However, “China has not been sitting on its hands waiting for its economic development to be choked.” China has been leveraging its particular advantages – its huge internal market, its dominant position in manufacturing, its education system, massive funding for research, and its “socialist economic planning which can set national industrial policy to undertake long term strategic initiatives” – in order to break the US’s technology siege.

In August 2023, Huawei released the Mate 60 pro, powered by a Chinese-manufactured 7nm chip – “precisely the kind of processor that the US sanctions had sought to prevent with their stated goal of denying China access to 14nm and below chip technology.” Industry insiders expect that China will soon be able to produce a 5nm chip. “These releases and announcements indicate China has weathered the storm and is poised to break through the siege that the US sanctions have sought to enforce.”

Sinha concludes that the US’s chip wars are destined for failure.

“Despite its head start in semiconductor technologies and massive financial resources at its disposal, the US, under neoliberal capitalism, is unlikely to be able to put policies in place to be able to remain ahead of China in the long run.”

The chip wars launched by the United States and its allies against China show no signs of abating and have escalated further in 2023 with indications of more to come. These wars are, in effect, a siege on China’s technological progress and economy. These across-the-board sanctions on leading-edge semiconductor chips, technology and equipment are a desperate attempt by the US to hold on to its geopolitical hegemony.

Background

While people are focused on the Ukraine war and Taiwan as frontiers of the geopolitical tussle between the US-led western alliance and the emerging powers of China and Russia, another front where the battle is being waged is in the tech domain – specifically, the semiconductor sanctions that the US is using to curtail China’s access to advance chips and technology to manufacture them. The US’s excuse for these measures is framed in military terms, saying that advanced semiconductors enable China to produce advanced military systems and improve the speed and accuracy of military decision-making. The tired western bogeyman of human rights violations is also cited as a reason for these sanctions. The sanctions are a naked attempt by the US to wage economic war against China. Having already lost its manufacturing leadership due to outsourcing production, the US is critically dependent on its lead in advanced technologies to retain its global dominance. With China catching up and, in many cases, leapfrogging the US in frontier technologies, the US sees the denial of semiconductor technologies with its outsized impact on modern production and economy as an effective mechanism of keeping China down. These actions are akin to technology denial regimes that the US, along with its allies, implemented during the Cold War.

The current round of technology sanctions by the US started in 2018 under the Trump administration. With the US increasingly getting concerned with China’s progress and leadership in telecommunications, especially in 5G, the US barred procurement of Huawei and ZTE equipment by all US federal government agencies, citing security concerns. This was especially ironic given the Snowden revelations about all leading US telecom equipment makers routinely having backdoors in their equipment for snooping purposes by the US intelligence agencies. The ban was preceded and followed by intense US lobbying worldwide, asking foreign governments to implement similar restrictions on Huawei. In December 2018, Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou was arrested in Canada on US request under the pretext of violating US sanctions against Iran. These actions wouldn’t suffice as Huawei was already the global leader in 5G technology, having become the world’s largest manufacturer of telecommunications equipment and the second largest manufacturer of mobile phones, supplanting Apple from that position. In May 2019, the US cut off Huawei from access to American technology. This not only cut off Huawei from procuring US chips but also from designing and getting the chips made from foundries such as TSMC, as those also depended on US technology. On the software side, Google announced that it would cut Huawei’s access to the Android platform. These moves were a fatal blow to Huawei’s phone business as Huawei had no short-term solutions for the loss of access to mobile chips. Their telecom equipment business (such as bay stations) survived as it didn’t depend on leading-edge chips and could be procured locally.

The tech sanctions wouldn’t stop at telecom equipment or Huawei but soon broadened to encompass China’s access to all leading chips and chip manufacturing technology. SMIC, China’s leading semiconductor foundry, was barred from purchasing the leading EUV lithography machine from a Dutch company called ASML in 2019. ASML is the only company producing these EUV lithography machines, each valued at more than 200 million dollars, which are required to manufacture the most advanced chips of 5nm or below (nm stands for nanometers and is a measure of transistor density with lower nm implying higher density and more advanced fabrication processes). ASML uses US technology, which allowed the US to deny ASML the right to sell the machines to SMIC. In 2020, SMIC like Huawei was put on the entity list, blocking its access to all US technology. The new Biden administration further expanded the tech sanctions, and by 2021, hundreds of Chinese companies were also added to the entity list. These actions targeted telecom, semiconductor, artificial intelligence, quantum and super computing companies. By 2022, across-the-board sanctions were placed on China to restrict its ability to import advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers, and manufacture advanced semiconductors. The sanctions would also include any company that uses US technology or products. They were effectively meant to decouple the supply chain of the US and its allies from China. The US managed to coax Japan, South Korea and the Netherlands into joining it in restricting exports of advanced semiconductor tools to China. Finally, in October 2023, the US further tightened the already draconian chip sanctions, restricting China’s ability even to acquire talent. This round was focused on AI chips and silicon wafer fabrication equipment, plugging any loopholes in the previous round of sanctions. They include a ban on ASML DUV lithography machines, one generation older than the already banned EUV machines. In late December 2023, the US announced it would launch a US semiconductor supply chain survey to identify how US companies are sourcing so-called legacy or mature chips (28nm and above) to “reduce national security risks posed by” China. Until this latest announcement, the US efforts targeted the denial of advanced chip (below 14nm) technology to China. The survey’s intention seems to be to deny China market access for the mature chips that China looks set to dominate, which would ensure complete decoupling between the western and Chinese semiconductor supply chains.

Breaking the siege

Meanwhile, China has not been sitting on its hands waiting for its economic development to be choked. China is the largest consumer of chips, consuming 40 per cent of chips produced globally and importing well over 400 billion dollars annually. China has long recognised semiconductors as a foundational technology, and achieving self-sufficiency in it is a strategic national priority critical to China’s sustained growth and competitiveness for the coming decades as it transitions into a developed economy.

While the sanctions regime has hit Chinese companies, especially Huawei, hard and exposed weak links in China’s chip supply chain, the last year has seen significant progress by Chinese companies. On the software side, Huawei announced breakthroughs in Electronic Design Automation (EDA) tools for designing chips at 14nm and above. Huawei also announced the launch of HarmonyOS for smartphones, replacing Google’s Android Platform from which it is banned.

In August 2023, Huawei released its new 5G phone, the Mate 60 pro. This satellite-capable phone stunned the US and the tech world as it was powered by a 7nm chip called the Kirin 9000s manufactured by SMIC. This 7nm chip was precisely the kind of processor that the US sanctions had sought to prevent with their stated goal of denying China access to 14nm and below chip technology. Further, there is speculation that Huawei is working on releasing a 5nm AI Chip as a successor to its Ascend 910B AI chip. Until now, it was assumed that China would be unable to mass produce 5nm chips without access to ASML’s EUV lithography machines. Huawei’s announcement was followed by Chinese carmaker NIO’s announcement of having developed a 5nm chip for autonomous driving.

YMTC surprised the tech world by releasing a 232-layer 3D NAND SSD chip – the most advanced in the world, dethroning memory chip giants like Samsung Electronics, SK Hynix, and Micron Technology. This is despite being put on the US Entity list in 2022.

Another Chinese chipmaker, CXMT, presented a paper showcasing the design of the most advanced DRAMs – indicating its design capabilities for 3nm gate-all-around (GAA) transistors.

These releases and announcements indicate China has weathered the storm and is poised to break through the siege that the US sanctions have sought to enforce. While the sanctions exposed weaknesses in China’s semiconductor supply chain, they galvanised renewed efforts to achieve self-sufficiency and provided a rare opportunity for domestic companies to sell to the large internal market, which has been dominated by foreign players until now. Despite these major advances, China remains far behind in the crucial area of Lithography machines, which are critical for making the most advanced sub-5nm chips. However, there are reports that Chinese firm SMEE has achieved a breakthrough and could start shipping China’s first indigenously produced 28 nm lithography machine – a huge leap over the 90nm machines that they are currently producing. While this would still be behind the EUV machines from ASML, they would catch up to ASML’s DUV machines.

Counterattack

China is not just content with trying to break the semiconductor siege but has now started hitting back. In May 2023, China took a page out of the US playbook and banned Micron chips from its critical domestic IT infrastructure sector, citing “security concerns”. Then, in July, China unveiled export control restrictions on gallium and germanium, which are critical raw materials for many types of semiconductors. China is the leading producer of these materials – producing 60 per cent of the world’s germanium and 80 per cent of the world’s gallium supplies. While these are found in other countries as well in abundance, starting mining operations takes time, which could result in disruptions in the global semiconductor supply chain. Additionally, China, the world’s top producer of rare earth metals, tightened control over their exports and banned the export of rare earth processing technology in December, which could hamper mining efforts in other countries as well

Following the release of Huawei’s Mate 60 pro smartphone, China banned employees of state firms and government departments from carrying Apple’s iphone to work. While these measures are not nearly as restrictive as the US sanctions, they are a shot across the bow that China can also play the same game.

Another front on which China can seriously hurt US interests is in the legacy (28nm and above) chip market. This is a huge market as the advanced 10nm and below chips comprise only 2 per cent of the market. In the legacy space, China already has the technology and is ramping up production capacity. By the end of 2024, the capacity for legacy chip production will be expanded to 32 fabs in China. Chinese companies could grab market share from entrenched western players such as Infineon, Analog Devices, Texas Instruments, ST Microelectronics and NXP Semiconductors, eating into their revenues and fat profit margins, which could then be reinvested in furthering R&D efforts in the advanced chips.

Future

The US chip containment policies on China don’t seem to be working, and China appears to be at the cusp of breaking out of this siege on multiple fronts. While in some areas, China’s progress will be hindered, in the long run, such policies will fail and come back to bite the US as their companies would lose the biggest market for such chips. The Semiconductor Industry Association argued this in their 2021 report, ‘Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Supply Chain in an Uncertain Era’. They had said that de-linking from the Chinese market would lead to China developing its indigenous manufacturing base and deny the US companies the large surplus they currently make from the Chinese market. CEOs of leading western semiconductor companies such as NVidia and ASML have been arguing similarly.

The current approach of packing more and more transistors into a silicon die is running into the limits of physics. As the industry has moved from 5nm to 3nm and, in the next couple of years, 2nm process technologies, we have hit the limits of how far we can go. Below 2nm, a phenomenon known as quantum tunnelling effect causes electrons to jump across barriers, resulting in unreliable transistor behaviour. Making further advances in computing would require alternate strategies. Research on advanced packaging techniques for building things called chiplets, which allow smaller chips to be combined into a larger processing unit, is promising. Further down the road, Quantum computers can provide a leap forward in computing power. China is investing heavily in these research areas as a path to leapfrog the west in computing technologies.

Even though the US and its allies – the EU, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan – are still ahead of China in semiconductor technology, China has some inherent advantages that will ensure that technology denial regimes will not work in the long run. These include China’s huge internal market – the largest in the world for semiconductors, its dominant position in manufacturing, education policy with some of the best technology institutes in the world, which churn out the largest number of STEM graduates, massive funding for science and technology research and its socialist economic planning which can set national industrial policy to undertake long term strategic initiatives. Despite its head start in semiconductor technologies and massive financial resources at its disposal, the US, under neoliberal capitalism, is unlikely to be able to put policies in place to be able to remain ahead of China in the long run.