In the following article, Russel Harland (Deputy Branch Secretary and International Relations Officer, Surrey County UNISON, and a member of the Friends of Socialist China Britain Committee) provides a detailed and throught-provoking description of his experiences on our recent delegation to China.

Discussing the delegation’s field trip to the Beijing headquarters of the ‘12345’ service hotline, Russel observes that this is an example of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in action, using all available resources to work for the common goal of serving the people while responding to reality in the process.” He contrasts this with his own experience working in service provision in Britain: “There were many occasions that I knew when giving vulnerable people advice, either in their homes or on the phone, that it was mostly theatre given the constraints on public services in Britain.”

Russel writes that “fundamental to our visit, unsurprisingly, is what you could call our red education”. Through the Chinese presentation of their own historical and ideological trajectory, it becomes clear that “the red gene flows through the life blood of everything that China is trying to do.” Reflecting on his experiences growing up in Belfast, Russel notes: “The battle for symbols is an important arena on the journey of any country’s rejuvenation, known only too well by those us from former colonies who have spent a lifetime walking past statues and symbols of our colonial oppression… After what our delegation experienced during our visit in China, the North of Ireland has some way to go in matching China’s cultural regeneration before it can truly unburden itself from the past.”

The article also explores the nature of China’s evolving Marxism, in particular Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. Russel emphasises the importance of casting off New Cold War propaganda – and deep-rooted ‘yellow peril’ racism – in order to understand the reality of China today.

It is vitally important for anyone wishing to understand contemporary China, that we attempt to claw ourselves out of the ideological pit of ignorance whence we bathe in untruths, which are then nonchalantly echoed as informed opinion on Xi Jinping, and China in general. Centuries of constructed racism, which we Irish understand only too well, against China from the West, with the alleged threat of the “yellow peril” lurking in the shadows ready to pounce on our “freedoms,” distorts reality and the standing in which President Xi is held, both in China and the non-western world.

Russel concludes: “The Friends of Socialist China 2024 delegation to the People’ Republic of China has born witness to an inspiring alternative that truly puts the wellbeing of all its population first.”

Russel is among the speakers at our webinar on 16 June 2024, China proves that a new world is possible! Delegates report back from China.

A chance quip by a comrade during a discussion on Chinese food one evening stimulated my reflection on the world that had opened up to me before my participation in the 2024 Friends of Socialist China (FoSC) delegation had even been confirmed. For around five years I had been attending online events organised by groups such as No Cold War Britain, the International Manifesto Group, and Friends of Socialist China, where I took inspiration to begin researching Chinese revolutionary history, economics, and Marxist theory. As a child of “The Troubles” in the North of Ireland, as it’s euphemistically known, I was a latecomer to Marxism as a mature student at university in my late thirties. The subsequent new focus on China led me to embrace a world of possibilities that would sit much more comfortably with my working-class experience and global south allegiances.

Reading from many sources, old and new, from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping, I began to formulate a tentative overview of the historical and contemporary Chinese experience, particularly from the time of China’s defeat to the British in the first Opium War in 1840, which ushered in the ‘century of humiliation’. Around this time in Ireland, Britain’s bloody footprint continued to be stamped on the colonised population, as an Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger) was set to ravage the country with devastating consequences still felt to this day as the outcome. Back in China, the crumbling dynastic society was violently exploited and reduced to extreme poverty by foreign invaders, mainly from the industrialised countries of the West and Japan, which ultimately sowed the seeds for the Civil War from 1945-49, which saw the defeated nationalists of the Guomindang retreat from mainland China to Taiwan. Bear in mind that China’s average life expectancy pre 1949 was just 36 years. Thus, the ‘century of humiliation’ left a deep scar on the population’s psyche.

Yet, in all the darkness there shone a glimmering of hope as the embers of something new began to spark. The second half of the century of humiliation witnessed the introduction of Marxism into Chinese Society, spearheaded by Li Dazhao, which then led to the formation of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1921. Mao Zedong, famed for his ability to relay Marxism to the masses by writing in simple and accessible terms,wrote in 1937:

“We must use Marxism, which is positive in spirit, to overcome liberalism, which is negative. A Communist should have largeness of mind and he should be staunch and active, looking upon the interests of the revolution as his very life and subordinating his personal interests to those of the revolution; always and everywhere he should adhere to principle and wage a tireless struggle against all incorrect ideas and actions, so as to consolidate the collective life of the Party and strengthen the ties between the Party and masses…”

As a result, armed with Marxist theory, inspired by the Russian revolution, Mao Zedong built a revolutionary movement, and despite the odds and impoverished conditions secured victory. A new dawn had broken as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was declared on 1 October 1949 which set the country on the road to development based on scientific socialism.

We must remember though that China is much more than the last two centuries. In the formidable words of Victor Gao, China is a 5000-year-old civilisational fact. This bears contemporary relevance for those so-called human rights defenders engaging in scurrilous anti-China talking points emanating from destabilising sources in the West, as it reveals that China’s borders have remained largely the same during this long, sometimes turbulent history, with some differentiation in those alleged “disputed territories”, such as Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. According to Kishore Mahbubani, there are ‘some hard political realities that cannot be changed’ in China by any leader,and the territorial integrity of the country is one of them. Rather than regurgitating flippant and ignorant remarks about China, people in the West should be mindful that humanity needs engagement, not more estrangement during what appears the decaying stage of American Hegemony.

The contrast between the Chinese and Irish experiences of the 20th century is stark. In Ireland, when an already dying James Connolly was carried on a stretcher, tied to a chair, and executed by the barbarous British for his heroic part in the Easter Uprising of 1916, it is said that Ireland’s chances of a Socialist Republic died too. Without Connolly’s Marxism and indomitable voice, an unfulfilled void was left in Ireland, which was soon to see an undemocratic partition in the north of the country which became the Protestant-dominated Northern Ireland. In the post 1949 years, Catholic Ireland in the south was to totally embrace the “red scare” of anti-communism. By the time Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up got underway in 1978, Northern Ireland was witnessing another bloody year of conflict, as the British government was found guilty by the European Court of Human Rights for ‘inhuman and degrading treatment’ of innocent people snatched from their homes by the British army and interrogated in 1971. At this point, the Good Friday Agreement, which would give parity of rights to all citizens in the gerrymandered statelet, was still 20 years away.

This is some of the historical baggage that I was carrying prior to landing in Beijing on Sunday 14 April, although I tried to leave as much of it as I could back in London, in order to approach this delegation with a true open mind. The delegation was made up of 14 people of various ages, experiences, and backgrounds, coming from Ireland, Britain, and the US, but expanding more globally in their origins. For many of us this was our first time in China.

We were met at the airport by our three Chinese representatives from CNIE (China NGO Network for International Exchanges) Ma Jingjing, Xu Luning, and Liu Huihui, who, along with many other people during our stay, played an invaluable role in keeping us on schedule and in the right place during our 10 days in China. I think it is fair to say that by the time that our stay in China came to an end our three hosts had become comrades due to our mutual respect and shared values.

We visited five cities, starting in Beijing, then Jiaxing and Hangzhou (Zhejiang province), before ending our trip in Siping and Changchun (Jilin province). After lingering around the hotel on the Sunday, getting to know each other a little, buddying up, we were swiftly whisked off to the Beijing headquarters of the ‘12345’ hotline on the Monday morning. Up until now all my knowledge of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics was based on books. I was soon to be swept off my feet in fevered awe at what I observed during our first site visit.

In my professional life I have worked supporting prisoners, people living with dementia, marginalised groups, and vulnerable people trying to access social care via the very same kind of government hotline we were about to visit. I have witnessed and listened to people at their most vulnerable, sometimes people who have been cast aside by society or deemed no longer useful because there is no surplus value to be exploited. It is a sobering experience that tends to make you see life from the worm’s eye view, to steal the epithet often given to the works of Maxim Gorky. To see the ‘12345’ in action and to learn of its successes was mesmerising.

As detailed by my delegation comrades Roger McKenzie and Carlos Martinez in their respective articles, the ‘12345’ is an all-in-one 24-hour government service hotline that takes over 60,000 calls a day in serving the Beijing municipality. The average wait time for each call is around 15 seconds, with each enquiry forwarded onto the relevant government body to respond within seven days, with a 90% satisfactory rating. Being an all-in-one service, the calls are diverse, and range from social care to highway maintenance, to even the whimsical in making sure the pandas in Beijing Zoo are fed according the Marxist principle of “to each according to its need”. The successful use of technology and data in developing the service over 30 years has meant ‘12345’ has been replicated across the country. This is Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in action, using all available resources to work for the common goal of “serving the people” while responding to reality in the process. You could see the collective pride on the staff’s faces in their work, safe in the knowledge that whomever of the 1500 staff worked the shifts at ‘12345,’ they were going to make a positive difference to people’s lives.

The contrast to my own work experience could not have been starker. There were many occasions that I knew when giving vulnerable people advice, either in their homes or on the phone, that it was mostly theatre given the constraints on public services in Britain. Ireland and Britain are full of conscientious workers willing and eager to positively contribute to society only to be ground down by decision makers with an alternative agenda not conducive to broader public wellbeing. The British state has a long history of being creative in inflicting harm on the most vulnerable, with one such example being the 1695 Penal Laws in Ireland which brought great poverty and marginalisation, mainly to Catholics, culminating in mass emigration to escape the destitution; an ominous sign of Ireland’s future.

Contemporarily, since 2010 Britain has been living through the “austerity years” which have brought immense financial hardship to those least able to bear it, such as people with disabilities, the poor, racial and ethnic minorities, single parents, women, and children. In a 2018 report for the UN, Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Professor Philip Alston wrote that under the rubric of austerity and saving the public finances, British politicians made the political choice in 2010 to try and ‘achieve radical social re-engineering,’ by seeking to remove the wider social safety net built in the wake of the second world war, while also removing the post-war values that underpinned it. Austerity has recently undergone a revitalisation, with British workers currently navigating what has become known as the “cost of living crisis,” as the reduction of living standards for the working class continues unabated.

Back on the bus after leaving ‘12345’ there was a buzz of enthused conversation taking place as the delegation started to process the immense social benefits of this successful government helpline. However, before too long we were set to be greeted at our next destination. This was to be the nature of our 10-day delegation in China as our senses took a rollercoaster ride of information gathering in our whistlestop tours of historical revolutionary sites, exhibitions centres, museums, think tanks, universities and academies, amongst other places. Not to mention the dialogues with our hosts and discussions between delegation comrades.

At the Peking University and Red Building, we were given a guided tour and presentation (pictured above) at the site of the CPC’s early activities in the premises used in Beijing that fomented the revolutionary cause in China. We jostled for space with members of the public beaming with pride at the contribution their ancestors made to the building of the People’s Republic of China. The walls were adorned with artefacts, pictures, and detailed descriptions of what took place in the building in those early revolutionary years. It is worth noting that some of those revolutionaries pictured did not stay the course of the revolution, but their contribution is rightfully still documented. This was replicated in the Sipingzhanyi Memorial Hall in Siping, Jilin, where war hero Lin Biao is given pride of place as you enter the museum, despite his ignominious demise in a plane crash fleeing China in 1971.

A particularly enjoyable aspect of the trip was being around the universities and the CPC cadre academies. One of our first round table discussions took place when we visited the School of CPC and Party Building at Renmin University of China (RUC). Renmin has 28,649 full-time students at the university including 5044 graduates pursuing doctorates, as well as 1060 international students, with 11 master’s programs on offer in English.

It was during these dialogues that Xu Luning, our translator, established a fan club among the delegation with her sharp intelligence and skilful application of her job. Equally, CNIE program manager Ma Jingjing quickly exercised her composed leadership as our interlocutor during these interactions, as well as when we visited new locations.

The discussions themselves were formally respectful with protocol to uphold on each side. Our delegation leader Keith Bennett demonstrated his masterful knowledge of Chinese history, culture and Marxism, setting the exchanges off on the right tone. Equally, co-editor of Friends of Socialist China (FoSC) Carlos Martinez, known to many Chinese comrades through his books, activism, and social media presence, was on hand to support Keith with formalities and introductions. The dialogues were fascinating and absorbing. At various times the rooms almost shook with enthusiasm from both sides, so keen were people to contribute and engage. This was especially evident at Jilin University, Changchun, an educational institution of 72,033 full-time students, 9,135 in doctorate programs, and a mammoth 2,476 full-time professors, where we sat adjacent a packed hall full of master’s students, PhD’s, and teaching staff, all keen to counteract the bewildering misrepresentation of China they read and hear from Western sources.

Regretfully the meetings were often constrained by time, but not before agreement was always reached that this was just the beginning of the partnership between FoSC and the respective institutions. One such example of this haste was when we visited the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), which is China’s leading non-governmental think tank, headquartered in Beijing, which employs over 100 full-time researchers and professionals, with many branches around the world. After a brief tour of the office, it felt like we had only just begun our dialogue when our tight itinerary dictated that the meeting had ended. The discussions continued with our CCG friends as they escorted us down to our bus. One of my delegation comrades commented that I appeared to be engaged in a heated discussion with one member of CCG. I said no, it was good, we were both speaking rapidly, and when he informed me that “China had some issues with human rights”, I replied “no doubt,” before adding that “China must not be held to a different standard of accountability that the West fails to uphold itself”. A recipe for unequal partnership. We departed on good terms.

Fundamental to our visit, unsurprisingly, is what you could call our red education.

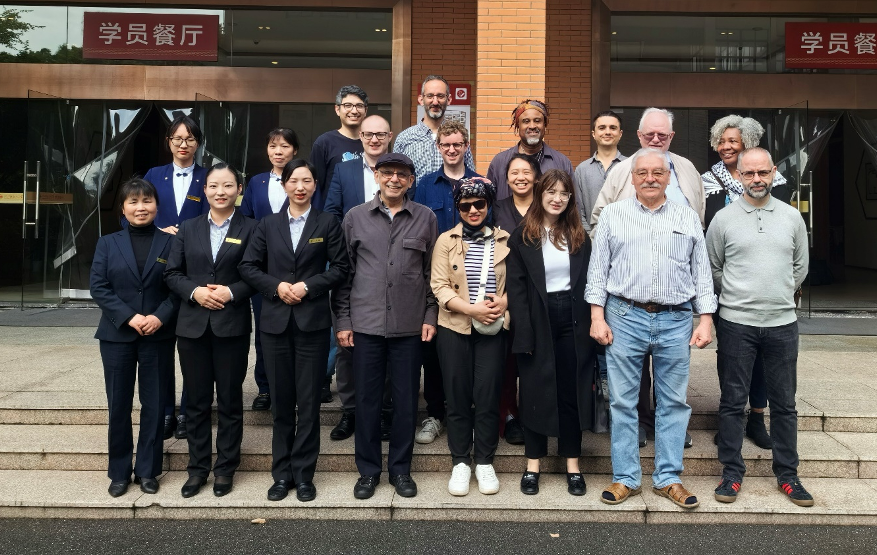

Throughout the five cities we visited the red gene that flows through the life blood of everything that China is trying to do is on display in one way or another. In the above picture are some of our FoSC delegates together with our Chinese comrades in the glorious lobby of the CPC Academy in Changchun. This scene was replicated throughout the places we visited, like the beautiful statue of Marx and Li Dazhao in the gardens of the Zhejiang Redboat Leadership Academy in Jiaxing, or the giant statue of Mao Zedong outside the Changchun Film Studio. Equally the hammer and sickle is everywhere; from the stunning ceiling of the Revolutionary Memorial Hall in Jiaxing to the field behind the agricultural centre we visited outside Siping. All of which were incredibly stimulating.

The battle for symbols is an important arena on the journey of any country’s rejuvenation, known only too well by those us from former colonies who have spent a lifetime walking past statues and symbols of our colonial oppression. American writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin famously wrote:

“It took many years of vomiting up all the filth I’d been taught about myself, and half-believed, before I was able to walk on this earth as though I had a right to be here.”

In the North of Ireland as a result of the Good Friday Agreement there has been a revival of the Irish language, which now enjoys formal recognition. Equally just this year two statues have been unveiled at Belfast City Hall, one of Mary Ann McCracken, a social reformer, abolitionist and educator, together with Winifred Carney, ‘adjutant in the Irish Citizen Army and James Connolly’s personal secretary and political confidante’ during the 1916 Easter Uprising. These two important expressions of decolonisation would have been unfathomable anytime during my childhood. However, after what our delegation experienced during our visit in China, the North of Ireland has some way to go in matching China’s cultural regeneration before it can truly unburden itself from the past.

Arguably the most important aspect of our red education in China was to absorb and bear witness to the theoretical foundation of Marxism, which floats in the air as a caressing guide, with Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era the current ‘ideological banner’ of the country. This latest manifestation of Marxism-Leninism adapted to a Chinese context is a continuation and development of Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of the Three Represents by Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao’s Scientific Outlook on Development. Each of these provides Xi Jinping with the collective historical wisdom of the CPC to develop Chinese Marxism to meet the demands of China’s current stage of socialist development. In this deliberation I am reminded of these words from Antonio Gramsci:

Socialism is not established on a particular day – it is a continuous process, a never-ending development towards a realm of freedom that is organised and controlled by the majority of citizens, the proletariat.

When I first began to read Xi Jinping a few years ago, I was invigorated by the moral intensity of his words where he talked of eradicating poverty, common prosperity, and showing respect and love for ‘those people in straitened circumstances.’In Britain declarations such as these by governing politicians would justifiably be met with derision as Oxbridge educated politicians are the epitome of entitled detachment, duplicitousness, and symbolic violence. For Xi Jinping, his steel was tempered by his formative years as a party official in one of China’s poorest places, living with the locals, sharing their experience, absorbing their day to day life over many years, while also ‘tackling poverty, environmental issues, corruption, and improving education and the protection of minorities’.

President Xi again gave us another glimpse of his personal development when he wrote that ‘reading invigorates my mind, gives me inspiration and cultivates my moral force.’ It is his love of reading, specifically Russian literature, which made me feel some kind of connection with the Chinese president. I pondered over whether he had worn out his copy of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons; or had he paced the room reading aloud Razumikhin‘s monologues in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment; perhaps he passed on his copy of Tolstoy’s War and Peace to a person in ‘straitened circumstances’ as I had done with a prisoner I once supported; no doubt in reading President Xi’s words he had plucked worldly wisdom from the short stories of Anton Chekov.

It is vitally important for anyone wishing to understand contemporary China, that we attempt to claw ourselves out of the ideological pit of ignorance whence we bathe in untruths, which are then nonchalantly echoed as informed opinion on Xi Jinping, and China in general. Centuries of constructed racism, which we Irish understand only too well, against China from the West, with the alleged threat of the “yellow peril” lurking in the shadows ready to pounce on our “freedoms,” distorts reality and the standing in which President Xi is held, both in China and the non-western world. This is in part due to China’s promotion of peace, diplomacy and development based on mutual benefit through the Belt and Road initiative launched by President Xi in 2013. Naysayers would do well not to simplistically refer to Xi Jinping as a demigod or dictator, who himself cautions against ‘relying solely on external forces or blindly following others; doing so inevitably leads to failure or subservience’. President Xi is predominantly guided to serve the people of China by his Marxism which is applied in his ethical approach to other human beings. Once more I am directed to the words of Gramsci who states:

‘Marx is for us the master of spiritual and moral life, not a shepherd wielding a crook. He is the stimulator of mental laziness, the arouser of good energies which slumber and which must wake up for the good fight.’

The second part of our trip found us in Zhejiang province which is located in the south of the Yangtze River Delta on the southeastern coast of China. It is said that Zhejiang boasts ‘a unique charm of the integration of history and reality,’ with natural scenery and historic sites of interest, including the West Lake in Hangzhou, and the Red Boat South Lake Memorial Hall, the birthplace of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in Jiaxing. Zhejiang province has a population of over 60 million, with the provincial capital of Hangzhou accounting for around 12 million of that total, and Jiaxing making up over 3.7 million.

It was in Zhejiang province that I began to comprehend a little more the theory and practice that is distinctive to China’s successful development. When observing how ordinary people interact with one and other, as well as talking to our Chinese comrades during our visits or on the bus, you begin to capture a flavour of the collective consciousness that drives China forward. This is not the austere or robotic effect that Western liberals would have you believe, but a progressively energetic instinct that conjures up Mao Zedong’s theoretical concept of ‘the mass line’, where all citizens are true stakeholders in society, confident that their wellbeing is best served by the structure of China’s political system. This was encapsulated in the Hangzhou Urban Planning Exhibition Hall where citizens can see in 3D digital splendour what the next stage of development will be, juxtaposed to the stage of development they have come from. If Britain had a similar exhibition hall they would be showing urban destruction yesterday, more today, and lots more planned for the future.

The first structural example we were shown of Zhejiang’s people-centred development, was a visit to the Luli Future Community in Jiaxing. This is a housing initiative encompassing Xi Jinping’s vision of balancing the present with the future, with the focus on affordability and wellbeing. This housing development includes reasonably priced childcare on site, fitness areas, and it even has exercise equipment that measures your blood pressure. Part of the rationale behind this initiative is that people would not have to travel off site for some of those essentials conducive to a healthy balanced lifestyle. The wellbeing theme continued when we visited the Party-masses service centre of Jiaxing, which was opposite the Revolution Memorial Hall on Nanhu Lake. This huge glistening building is, amongst other things, a mental health base with a psychological wellness centre where you can see a therapist within 24 hours of booking. It is worth pointing out that when something works in China it is replicated through other parts of the country when practicable.

Whilst driving from Jiaxing to Hangzhou at different times you are hit by the young vegetation everywhere. The motorway has beautifully pristine hedges that separate the lanes, which then become flowers as you get closer to the cities as the speed of traffic reduces. Equally the immaculate maintenance of all green areas around the cities is testament to the ecological consciousness that Xi Jinping set about instilling in Zhejiang around 2004 while Party Secretary of the province. The environmental problems that China has had in the past are well known, which the West has exploited to its fullest in their unique hypocritical way. However, China is a country that learns quick and acts faster and is the leading nation in green development around the world. This is the application of ‘crossing the river by feeling for stones,’ associated with Deng Xiaoping. For China, investment in developing its ecological consciousness has manifold benefits: from creating jobs; developing areas like the West Lake and the National Tea Museum for tourism; meeting global climate obligations; and also creating a visually pleasing environment that generates a soothing atmosphere for all citizens, irrespective of income.

When we visited the ancient water town of Xitang, pictured above, which is described as a ‘fictitious land of peace and happiness,’ I recall a conversation with Luning during our stroll around the picturesque setting regarding people of varying ages wearing traditional clothing. We both agreed it was delightful, and Luning told me it had become much more popular and affordable in recent years. During our conversation we discussed the past of both our countries and without saying, we understood that embracing the past on our own terms is a way of shaking off the alienation implanted on us by indifferent outsiders.

That evening, I sat with Liu Huihui during our evening meal. Huihui is the third of our Chinese hosts who travelled with us throughout our visit and was a reassuring presence on our excursions, always there if needed. I asked Huihui during dinner whether was she taught Marxism at school, to which she replied of course. She told me they are taught from four main texts books covering different topics at High School. I was fascinated and asked her again the next day. She wrote it down:

‘We will learn about the history of socialism from fantasy to theory to practice, productivity and ownership economy, materialist dialectics, historical materialism and other basic knowledge, and then combine with China’s national conditions, introduce China’s political system, economic system and so on…’

I showed my comrade Francisco Huihui’s message and he exclaimed, “China really is nurturing a new kind of human being.” Awestruck, we both deliberated the endless possibilities for young people’s creative development in an environment that encourages the study of reality and what wonderous possibilities it will mean for China, for us all!

On the final morning of our stay in the Zhejiang Redboat Academy as we left for the bus, the workers, who had treated us so kindly and made our stay so peaceful asked for a group picture. We obliged in a flash.

Prior to coming to China, I spoke with a Chinese comrade who was pleased we were going to Jilin as it would be an opportunity to see a more developing region of China in comparison to developed Beijing and Zhejiang. Jilin has a population of 23,470,000, with an estimated 4,800,000 of those in the provincial capital of Changchun, and the province was an important old industrial base for manufacturing and commodity grain which was vital for the PRC’s early development. Now Jilin is known as ‘the cradle of new China’s aviation, automobile and movie industry and also the cradle of people’s aviation,’ and of course there is the Changchun Railway Vehicles Co Ltd, ‘the largest manufacturer for rail transit passenger equipment in Asia.’ Equally Jilin is an important hub for other industries such as petrochemicals, food processing, healthcare, and ecological construction, with 42 percent forest coverage and one of the world’s highest-quality mineral water sources. Moreover, the province is rich in wildlife, with the sika deer, red-crowned cranes, Amur leopards, and Siberian Tigers all thriving in the Jilin environment.

I must confess, Jilin, in northeast China, which borders the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and Russia, was probably my favourite part of the trip. Of course, we already had seven or eight successful days behind us, built up a great camaraderie, and absorbed so much positivity from our day to day exchanges. Perhaps I was just savouring every last moment in the knowledge the trip was coming to an end. Either way, Jilin, specifically Siping, a city with a population of around 1.8 million people, which was dusty, somewhat dated, with some daring, if slightly surrealistic architecture on the outskirts of the city, radiated energy and was wholesomely uplifting. For some reason Siping reminded me of the northeastern Turkish city of Kars, as described by Orhan Pamuk in his 2002 novel Snow. Pamuk’s novel forlornly describes the political and cultural tension of East meeting West in an isolated part of Turkey close to the borders of the old Soviet republics of Georgia and Armenia. Unlike Kars described then by the novelist, the people in Siping conveyed no such pessimism with the atmosphere of the city portraying one beginning to emerge from chrysalis.

Our first stop before entering Siping City was a visit to an agricultural centre in Lishu County visited in 2020 by President Xi, who has shown a great concern to make sure that the precious black soil, which covers 65 percent of the cultivated land in Jilin, while producing over 80 percent of its grain, is protected for future generations. This highlights the seriousness of not only protecting Jilin’s huge agricultural industry but also safeguarding food security for 1.4 billion Chinese people. We then stopped off for a wonderful lunch in what appeared to be a roadside cafe, reminiscent of places I had visited as a child with my father during school holidays on his long trips as a lorry driver. Loaded trucks kick up dirt in both directions, moving with purpose, disciplined, unwilling to deviate from the task of driving China forward, unaware of our delegation, keen to contribute to the rejuvenation of the country. As we left the restaurant one of the delightful people who had helped serve us food, as seen in the picture below, had my dear comrade Francisco and I whirling like two catherine wheels in excitement at the genuineness exuding from our host, “we hope you enjoy China, we want you to invest in our country,” she said in broken phrases.

Next stop was Sipingzhanyi Memorial Hall in Siping where we were greeted by a welcoming party at the entrance, including a formidable young man dressed in a Soviet-style coat who ushered us into the hall to begin our tour. The museum was a wonderous memorial to the heroic actions of the CPC who fought four battles with the KMT during the war of liberation in Siping which made it become known as the ‘City of Heroes.’ At the end of the guided tour, we descended on the gift shop like gluttons, ravenous for red memorabilia, enthused by the chronicle of the local revolutionary history just recounted. The staff, mindful of our schedule, hurried to keep us on track, at which point my delegation comrade Danny Haiphong started nudging me saying “look at the police officer helping out in the gift shop, there’s no way that would happen in the States.”

With dusk approaching we left the memorial hall to walk onto the expansive Hero Square, appropriate in its vastness to enable peaceful reflection upon leaving the war museum. As we started to take pictures and wander, we noticed little groups of people singing traditional Chinese songs. Upon our approach, they nodded in appreciation and dedicated a few songs in our direction. In response we applauded in gratitude. It was such a beautifully serene experience that at once I wished to share it with all the people that I love, with everyone.

When we got to the hotel, I detached myself from the group, pounding a few miles on the treadmill in the hotel gym which overlooked the city on one of the upper floors. I then determined to take a lone walk down the huge street outside our hotel and take a video diary documenting our safety in China. However, two minutes into my walk I was attracted to the lights and shops to my right, and there at the first café on the left outside were some of the delegation drinking a few beers and eating meat skewers, which my comrade Sage insisted I must absolutely try. The conversation continued on various topics in which I felt somewhat disengaged, lost in my own world, watching the fleeting glances from curious young locals that our out of place group merited.

There is something about the collective consciousness we experienced in China that could evoke a hope long since vanquished in large swathes of the western working class. No longer should we throw our hands despairingly in the air and wallow in the doldrums of Ginsberg or the desolation of Kerouac. NO! China is more like the land of Audre Lorde, where the future has no need to be put on hold waiting for a new messiah, and ‘change is the immediate responsibility of each of us, wherever and however we stand.’ I never took that walk alone through Siping. Instead, I went back to my 11th floor hotel room and lay upon the bed, awake for hours, with my arms behind my head as the city lights shimmered through the window into my darkened room; my eyes wide open, my mind pulsating with energy, thinking a thousand entangled thoughts: thinking of China, of Belfast, of life, of my family in London, of the future.

A week after coming back to London from China I was back in Belfast for a trade union health and safety conference where I sat in the conference hall of the Europa Hotel with trade unionists gathered from across Britain and the North of Ireland. The regional secretary for Northern Ireland gave a welcoming address in which she mentioned the strangulation of public services in this part of Ireland. This is particularly detrimental given the problems of mental health, suicide and post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from the state of anomie, or psychological disruptor, that our post-conflict society has languished due to a failure to deal with the trauma of the past. Professor Philip Alston gives special mention in his UN report to Northern Ireland and its ‘persistent inequalities along religious lines,’ where ‘rates of long term unemployment are more than twice those of the UK as a whole.’ Consequently the British government has little to no interest in dealing with the past, being more concerned in legally covering up state crimes it committed during the conflict so it can live out its sick neo-colonial fantasies on the coattails of the fanatically crumbling American Empire, with the primary focus on attempting to prevent China’s rejuvenation.

The conclusion of the UN Special Rapporteur’s report on his visit to the UK states that the imposed poverty was a political choice and the resources where there to safeguard the poor. James Connolly warned as much for Ireland in an 1897 paper by way of saying that any green flag flying over Ireland will mean nothing to the working class if we are tied to the same corrupt economic system. Yet the Friends of Socialist China 2024 delegation to the People’ Republic of China has born witness to an inspiring alternative that truly puts the wellbeing of all its population first. To our own misfortune may the working class choose to ignore or not fight for such a path with the age of multipolarity upon us. My own task now is to take President Xi’s advice and to pursue depth. I may have visited the PRC but I have a long way to go before I can say I have reached China.

Thank you for such a moving, informative and genuine share of your experiences and thought.

Now I had the chance to read your article, Russ, I really enjoyed it, particularly the way you linked the Irish struggles to that of China. Also made me remember the wonderful comradely spirit expressed by our hosts and everyone during the trip. Thank you for great effort.