In the following article, which was originally published by China Today to coincide with the start of the Year of the Dragon, our co-editor Keith Bennett, noting that the Lunar New Year has increasingly become a common festival of people throughout the world, goes on to illustrate how it has become an integral part of British life, celebrated not only by the Chinese community and all those with a connection to China, but increasingly by people from all communities and all walks of life.

Keith notes how the celebration in London’s Chinatown, which had already become one of the largest and most spectacular outside Asia, was brought to Trafalgar Square by progressive mayor Ken Livingstone, and due in large part to the hard work and efforts of two great friends of China, the late Redmond O’Neill and Jude Woodward.

Highlighting how China’s late Premier Zhou Enlai had stressed that his country’s diplomacy rested on a tripod of state-to-state, party-to-party and people-to-people relations and that President Xi Jinping has often stressed that good people-to-people relations are the foundation for sound state-to-state relations, Keith concludes:

“British people from all walks of life and backgrounds have been increasingly taking Chinese New Year to their hearts. It has become part of our culture and calendar. This is one more reminder that Cold War hostility and bellicosity do not represent the interests of the people of any country and are therefore destined to fail.”

Chinese people, and people throughout the world, are looking forward to welcoming the Year of the Dragon, which falls on February 10, 2024. The Dragon is considered the most auspicious of the 12 signs in the Chinese zodiac and this year is specifically the Year of the Wood Dragon, the first since 1964. According to Lifestyle Asia, “Wood Dragons enjoy fulfilling careers. They’re likely to materialize all their ambitions into actions, coming up with truly revolutionary ideas.”

In the run up to the Chinese people’s greatest holiday, there has already been some good news. On December 22, 2023, the 78th United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution by consensus that, as from 2024, the Chinese, or Lunar, New Year shall be designated as a UN “floating holiday,” to be taken into consideration when drafting the world body’s calendar of conferences and meetings.

This might be best understood as a welcome and quite possibly overdue recognition of reality. The Lunar New Year has long since ceased to be solely a great festival for all Chinese people; for other countries and peoples in East Asia sharing a cultural heritage and numerous neighborly bonds with China; and for overseas Chinese and people of Chinese heritage on the five continents and across the four seas. It has increasingly become a common festival of people throughout the world.

In my country, Britain, it is, of course, a special occasion for our Chinese community and for all those of us with a connection to China. This naturally especially applies to Chinatowns, such as those in London, Liverpool (the oldest in Europe), Manchester and elsewhere.

The London Chinatown Chinese Association (LCCA), one of the U.K.’s most important Chinese organizations, long led by the indefatigable Chu Ting Tang, proprietor of the Imperial China restaurant, works hard throughout each year to stage one of the greatest and most spectacular Chinese New Year celebrations outside Asia, which attracts tens of thousands of people – not just Chinese people, but Londoners from every background in this most multicultural and multinational of cities, joined, too, by visitors and tourists from all over.

This great celebration had long since outgrown the crowded pavements of Gerard Street, Lisle Street, Wardour Street, Newport Place, and others in the heart of Chinatown, when Ken Livingstone, the progressive mayor of London, brought it to the heart of the capital in nearby Trafalgar Square.

This was a key part of Ken’s ambitious program to recognize and celebrate the city’s great diversity, from Ireland’s national Saint Patrick’s Day, to the Notting Hill Carnival (originally inspired by Claudia Jones, a communist of Trinidadian origin, who met Chairman Mao and is now buried to the left of Karl Marx), to the Eid, Diwali, Vaisakhi, and Hannukah festivals of the Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Jewish faiths.

None of this would have been possible without the devoted and tireless work of two great friends of China, who were mainstays of the mayor’s office and administration. Redmond O’Neill and Jude Woodward, socialists, Marxists, and internationalists, left us far too early, but we remember them not least at Chinese New Year. Its central place in London life is thanks in great part to them.

The Chinese New Year is also a focus for all in the business community with an interest in China and the Chinese market. This is now marked by an ever-increasing number of dinners and receptions, but the flagship event has long been the “Icebreakers” Chinese New Year Dinner, customarily held in the ballroom of the iconic Dorchester Hotel, home also to the China Tang Restaurant, founded by the late Sir David Tang, on Park Lane, and organized by the 48 Group Club. Originally hosted by the London Export Corporation (LEC), the first U.K. company to trade with the new China following the establishment of the People’s Republic, and founded by the late Jack Perry, it is now joined by the China Britain Business Council (CBBC) and the China Chamber of Commerce in the U.K. (CCCUK), and features keynote speeches by the Chinese ambassador and other VIPs, both British and Chinese. It has even received letters and messages of greetings from President Xi Jinping and other top Chinese leaders.

For the last couple of decades, the Chinese affiliates, and China interest groups, of the Conservative, Labor and Liberal Democrat parties have all also hosted celebratory dinners, although these have now been somewhat negatively impacted by the new Cold War mentality and the rise of neo-McCarthyism. My personal highpoint from these events – although they have also been attended by a number of serving prime ministers and receptions have been held at 10 Downing Street, the prime minister’s official residence – was when former Chinese Ambassador to the U.K. Liu Xiaoming joined Jeremy Corbyn, the first socialist leader of the Labor Party in at least eight decades, to celebrate at the Phoenix Palace, one of London’s most outstanding Cantonese restaurants, as well as brought the traditional lion dance to life at Labor’s headquarters.

But, as mentioned, Chinese New Year in the U.K. has now gone well beyond those with a specific China interest. It is, for example, marked with special projects and lessons in many of our primary schools up and down the country.

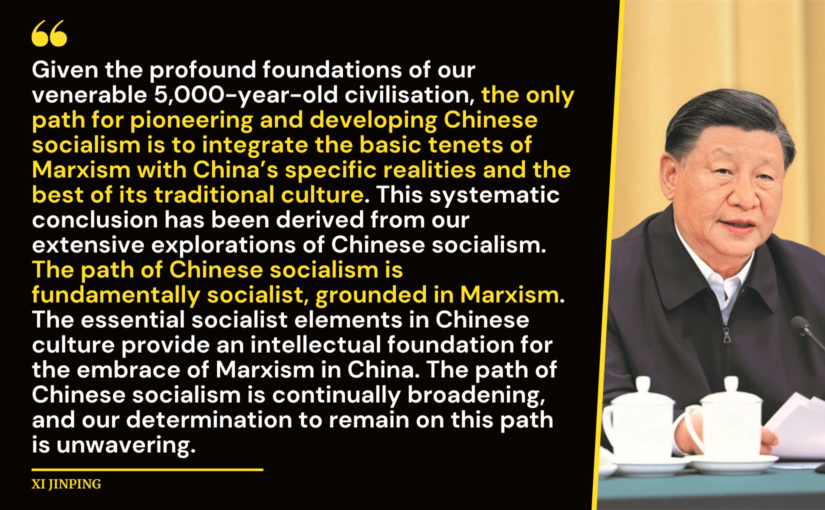

China’s late Premier Zhou Enlai, in my view the greatest diplomat of the 20th century, stressed that China’s diplomacy rested on a tripod of state-to-state, party-to-party, and people-to-people relations.

President Xi Jinping has often stressed that good people-to-people bonds are the foundation for sound state-to-state relations.

British people from all walks of life and backgrounds have been increasingly taking Chinese New Year to their hearts. It has become part of our culture and calendar. This is one more reminder that Cold War hostility and bellicosity do not represent the interests of the people of any country and are therefore destined to fail.

Happy New Year of the Wood Dragon! ![]()