In this thought-provoking, sympathetic, but not uncritical article, Andrew Murray addresses himself to the question of the significance of the Chinese revolution, which, he notes in opening, is “the most important single fact of 21st-century politics.” Andrew demonstrates this by noting that the rise of China is bringing to an end centuries of European/North American hegemony at a global level; is reversing the economic ‘great divergence’ that began with the opium wars of the mid-19th century; and is challenging the monopoly of global violence at the state level exercised by the United States and its allies. As a result, “unipolarity now faces a systemic negation,” with many countries of the Global South now having socio-economic options they did not previously, thereby creating the possibility of a more equal world.

Andrew points out that whilst the concepts of socialism and capitalism have universal application, they are not invariant. “It would be wrong to expect a civilisation as old and developed as the Chinese not to modify our understanding of these unfinishable categories.” He notes that in the 20th century, two tendencies struggled for hegemony in the global socialist movement – the Soviet model, which ultimately collapsed, and social democracy, which in reality was not socialism at all and which can be seen as a product of imperialism. Drawing on Marx’s concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the understanding of socialism as a transitional form, he notes that, despite certain claims to the contrary, “no society has developed much beyond the foundations of socialism … the relatively modest claims made by the Communist Party of China … may be much better founded than the more sweeping claims … [and] the suppression of capitalism by socialism will be the work of a very long time, with numerous zigzags and experiments on the way.”

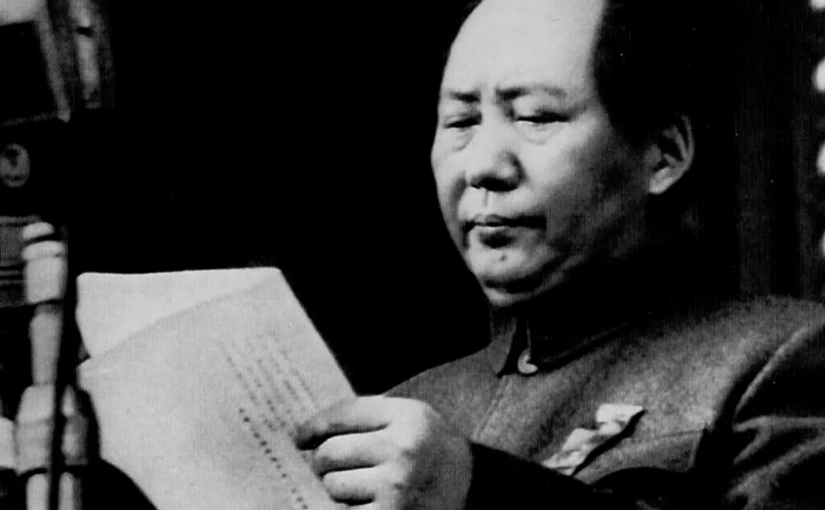

Regarding the concept of the ‘sinification of Marxism’, Andrew asserts that certain concepts of Mao Zedong and his comrades, such as placing the peasantry as a central revolutionary subject, the idea of surrounding the cities from the countryside, and the theory of new democracy, are of enduring importance. “China takes Marxism from the European labour movement and returns it to the world enriched, developed and nearer to universalism, but not, of course, ‘finished’.”

Turning to the changes initiated in China from the late 1970s, and the differences in line between Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, Andrew is of the view that “the former prioritised the transformation of social relations, while the latter prioritised the development of the forces of production. Either can be justified in Marxist terms.” In the author’s assessment, whereas Mao “fetishised” class struggle, his successors, such as Deng and Jiang Zemin, “radically diminished” its importance, “even as class differences have re-emerged quite sharply.” This, however, “did not make the People’s Republic a bourgeois society.”

Bringing the story up to the present, Andrew outlines Xi Jinping’s concept of six phases in the history of socialism, adding that what in China are referred to as the ‘four cardinal principles’, and which were originally advanced by Deng Xiaoping, “underline that there is no absolute rupture between CPC strategy today and that in Mao’s time. Mao himself was a flexible and sometimes contradictory thinker whose works can provide fertile justification for varying strategies.”

Without shying away from complexities, contradictions and caveats, moving towards his conclusion, Andrew notes that, “what is undeniable is that the future of socialism in the world depends very heavily on developments in China and on the leadership of its communist party. As Xi has said, without China socialism risked being pushed entirely to the margins of world affairs after 1991.”

In the view of the editors of this website, Andrew’s article is an important contribution to a vital debate that needs to be read and discussed seriously and widely. The author was previously the Chief of Staff at Unite, Britain’s second-largest trade union, Adviser to Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, and Chair of the Stop the War Coalition. He worked at the Morning Star daily newspaper, 1977-1985, and currently does so again. He is the author of a number of books, including most recently, ‘Is Socialism Possible in Britain?’, published by Verso.

The main themes of this article were first outlined by Andrew in his talk to the Friends of Socialist China meeting on the evolving significance of the Chinese revolution, where he exchanged views with visiting US professor Ken Hammond, at the Marx Memorial Library on 28 November 2022. This article was published in the 2023 edition of Theory and Struggle, journal of the Marx Memorial Library and Workers’ School, published by Liverpool University Press, who hold copyright. This accepted author manuscript is published under a Creative Commons Attribution License and with the kind permission of the author.

The broad significance of China’s rise is evident.1 It is the most important single fact of 21st-century politics and can be simply stated as follows.

First, it is bringing to an end two centuries of European/North American hegemony at a global level.

Second, it is reversing what has been called the ‘great divergence’ in economic power and prosperity, which began with the 19th-century opium war and opened up an enormous gap in favour of the west.

Third, it challenges the monopoly of global violence at the state level exercised by the United States and its allies.

In all these respects, China is bringing to an end the ‘unipolar moment’ that prevailed in world affairs after the end of the Soviet Union more than 30 years ago. Already weakened by US military defeats and the disastrous consequences of ‘Washington consensus’ economics, unipolarity now faces a systemic negation. At the global level, this means many countries of Africa, Asia and South America now have socio-economic options that they did not have previously. They have more room to shape their own futures. All this creates the possibility of a more equal world, with a lessening of the gross disparities that have been a central feature of the imperialist era.

In purely Chinese terms, the country’s development has led to a vast increase in prosperity for the Chinese people. Yet at the same time what was, under Mao Zedong, one of the most equal countries in the world has now become marked by dizzying inequality. Once rock-solid, if very basic, social security was comprehensively undermined and has only recently been reconstructed to some extent (it should be noted, however, that life expectancy has continued to rise throughout this period).

This has long raised the question among the left: what is the China that has done all this? A socialist state, or a capitalist one? What frames its development?

These are bigger questions than can be answered in a single article, particularly one by an author who claims no great expertise on China. Here I just want to advance some considerations for further reflection.

What is China?

To start with the basic question — is China a socialist country, or a capitalist one? — it is questionable that this is the right one to ask.

Socialism and capitalism are certainly social categories with universal application. That does not make them invariant. They were both framed in 19th-century Europe. It should hardly be expected that they would remain unchanged after their interaction with the diversity of cultures and civilisations across the rest of the world and nearly two centuries of time. In particular, it would be wrong to expect a civilisation as old and developed as the Chinese not to modify our understanding of these unfinishable categories. At any event, if China is either socialist or capitalist, it is unlike any other socialism or capitalism we have seen hitherto.

Here is a first complication. Socialists have a clearer sense of what capitalism is, because we all live and struggle within it. Its pillars — commodity production, the exploitation of labour, an alienated working class and endless capital accumulation — are familiar. Those of us of a certain age can also remember a capitalism with a very substantial public sector in industry.

As to what socialism is, we are on shakier ground. Two tendencies struggled for supremacy in the 20th century, but neither is in great shape today. The first was the Soviet model, based on overwhelmingly preponderant state ownership and working- class power articulated primarily through the unchallengeable leadership of a Marxist-Leninist party. In the Soviet Union and eastern Europe, that model collapsed. Its revival, despite the great achievements associated with it, seems improbable.

The second model was not really socialism at all. It was the managed, welfare capitalism that constituted the summit of social democracy’s achievements and, for the most part, its aspirations. This trend can be seen as a product of imperialism above all, which is why it has never enjoyed the purchase outside western Europe that it has done within it. It, too, points no way forward, and the embrace of a slightly diluted neoliberalism by its main protagonists over the past quarter-century has led it into a dead end.

Can an essence of socialism be extracted from this experience? The dictatorship of the proletariat was Karl Marx’s answer, focusing on the question of power. That power would be deployed to implement the programme sketched in The Communist Manifesto of 1848 and would operate, according to Friedrich Engels, in the fashion of the Paris Commune of 1871.

Their socialism is a transitional form, or the initial phase of communism distinguished by distribution according to work done, or bourgeois right. Much ink and some blood has been spilt in the history of Chinese socialism on the issue of whether, when and how to supersede bourgeois right.2 Perhaps this is the central tragedy of 20th-century socialism, arising as it did in countries where for the most part capitalism had only modestly developed and the bourgeoisie had scarcely consolidated as a ruling class.

At any event, we can say that working-class power as opposed to the bourgeois state is the precondition for socialism. The foundations of socialism surely include the circumscription of commodity production, particularly in the areas essential to human well-being, the elimination of exploiting classes (but not necessarily all class differences), a reduction in income inequality and the establishment of full social equality in respect of gender, race or nationality. It seems to me that anything more than that is contingent on circumstances, or awaits the full consolidation of socialism. The point is that no society has developed much beyond the foundations of socialism. Full socialism, which would include the disappearance of all class distinctions and the near-total elimination of commodity production, has nowhere been attained. The Soviet claim to have reached a stage of ‘developed socialism based on a ‘state of the whole people’ did not correspond to reality.

In this case, the relatively modest claims made by the Communist Party of China (CPC) for the development of socialism — that they are in the initial stages only, and that the transition to a fully socialist society will be the work of generations — may be much better founded than the more sweeping claims made regarding a relatively swift dash into a fully formed new society. If we have learned anything from the past hundred years, it must be that the supersession of capitalism by socialism will be the work of a very long time, with numerous zigzags and experiments on the way.

The sinification of Marxism?

Some of the same considerations must apply to the concept of the ‘sinification of Marxism’. Marxism was the product of the emergence of the working-class movement in Europe, of the analysis of the first capitalist societies, and was rooted in the western philosophical tradition, of Kant and Hegel, or more exactly in a critique of it. It is again inconceivable that Marxism would, could or should remain unchanged after the prolonged engagement with different societies, cultures and civilisations. Marxism is a method (historical materialism) but not a finished set of definitive conclusions.

The idea of the ‘sinification of Marxism’ therefore bears two meanings. The first is that it consists of the application of Marxism as a given set of principles to the particular social conditions of China. Indeed, Mao Zedong and his comrades set about this work. In particular, they placed the peasantry at the centre of communist politics as a revolutionary subject, and developed the concept of ‘new Democracy’ among other innovations. These are of enduring importance.

The second meaning posits the transformation of Marxism through the practice and thought of China, of the Chinese people (more than one-fifth of humanity) and the Chinese revolution. In this understanding, China takes Marxism from the European labour movement and returns it to the world enriched, developed and nearer to universalisation, but not, of course, ‘finished’.

There is no stark division between the two. A recent official publication of the CPC puts it thus: ‘The history of the Communist Party of China was formerly the history of the localisation of Marxism in China, but from now on it will be the history of the development of Chinese Marxism.’3 Here is the inversion of subject and object, from the local application of the Marxism of Lenin, Stalin and the Communist International to Chinese conditions to developing a new and distinctive Marxism that will doubtless have lessons for the rest of the world, albeit not as a new model.

So far, so good. But what is this Chinese Marxism? Again, we should look first of all at what the CPC says about its ideological foundations. According to its rules, the party has a six-layered ideology comprising Marxism-Leninism, Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping Theory, the Theory of Three Represents, the Scientific Outlook on Development and Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.4

The CPC has adopted the practice of embodying the ideas of each of its successive leaderships in a formulation canonised in its rule book. This is of doubtful utility except as a map to navigate the party’s ideological development. Clearly the six formulae cited above do not carry the same weight. Marxism-Leninism sits alone in this litany as a theory developed outside China and held to be of universal application. Mao Zedong Thought is perhaps itself transitional in that, while evidently Chinese in its origins and directed first of all to Chinese circumstances, it was held for some time by the CPC to have also been a universal development of Marxism. This the CPC no longer insists on.

The final four formulae — one for each leadership — have guided the CPC since its turn to ‘market socialism’ in 1978. They reflect Chinese conditions and are not held out as having more general application.

It is not necessary here to dilate much on the subject of Marxism-Leninism. It is understood, or often misunderstood, but its global significance in the 20th century is recognised. It was the doctrine of international socialist revolution, the Marxism of the era of imperialist wars and proletarian revolutions. It framed the Chinese revolution, contextualising national revolution and social modernisation (things accomplished elsewhere by bourgeois movements) within the world socialist revolution. Marxism-Leninism, and international communist leadership, meant that the CPC and the Chinese revolution could retain an overall working-class character and socialist orientation as it fought for national independence and new democracy while isolated from the anyway small Chinese working class for the most part.

The global movement gave a decisive imprint to events, at the same time as the Mao leadership adapted its general principles to Chinese conditions. It may be that the Chinese revolution was the greatest and most enduring consequence of the October Revolution in Russia. The issue of global framing has contemporary relevance too, as Chinese society develops in a world in which socialism has very largely otherwise disappeared as a systemic alternative and the world communist movement is a shadow of its former force.

It is often speculated that the Soviet Union could have survived had the CPSU followed a reform policy similar to that adopted in Beijing. Maybe so, although it is also true that China might not have developed as it did had the Soviet Union survived as a socialist state. Deng Xiaoping’s ‘southern tour’, which turbocharged market- oriented development, took place in 1992, a not-insignificant date.

Mao Zedong Thought — the original ‘sinification of Marxism’ — left lasting lessons too, as noted, particularly with regard to the revolutionary role of the peasantry. The revolutionary tactic of ‘the countryside surrounds the city’ has endured well, as recent events in Afghanistan have shown, allowing a socially moribund movement such as the Taliban to defeat US imperialism. There were interconnected nationalist and anti-imperialist aspects to Mao Zedong Thought, which remain part of the CPC’s orientation today.

Deng Xiaoping Theory

The main disjuncture is between Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. The latter formed the guiding principles of the period of ‘reform and opening up’ from 1978. The gap between the approaches of Mao and Deng is obvious. The former prioritised the transformation of social relations, while the latter prioritised the development of the forces of production. Either can be justified in Marxist terms, but there is little point in pretending that they are the same thing. Mao’s China was relatively poor and very equal; Deng’s China became much wealthier and much more unequal, to the point where one can speak of class stratification.

This is the key point, but which the CPC seems reluctant to acknowledge — the persistence of class contradictions. Whereas Mao fetishised class struggle in a socialist society, the concept has radically diminished in the CPC’s lexicon, even as class differences have re-emerged quite sharply. Mao saw, and exacerbated, contradictions and antagonisms where none had existed or where they were at least susceptible to peaceful resolution; Deng and subsequent leaderships have played down very real antagonisms that have arisen since the turn to the market.

This is theoretically disabling, and echoes the error made by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at its 20th congress in 1956. There the party leadership denounced the crimes of the Stalin period and at the same time prevented itself from understanding them by denying the persistence of class struggle under socialism through the embrace of concepts such as ‘the state of the whole people’, which in principle has no warrant in Marxism and also bore not much relationship to the realities of Soviet society and the functioning of the socialist state. Likewise the CPC leadership, in wanting to avoid any theoretical premise that might open the door to a rerun of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), has obliged itself to deal with sharp social contradictions while setting aside the compass for doing so. The CPC is far from repudiating Mao wholesale, as the CPSU did Stalin, but the departure from previous policy is if anything even more stark.

The Theory of Three Represents

Still, class contradictions develop whether or not they are acknowledged. The next- in-line theoretical lodestar — the Theory of Three Represents associated with the recently deceased Jiang Zemin — represented a high point of bourgeois-influenced thinking in the CPC, despite some neo-Marxist packaging. Coming after the end of the Soviet Union and the world socialist system, it represented an attempt to recalibrate the social base and mission of the CPC at a time when ruling communist parties had gone from being quite normal to anomalous on a world scale.

The Three Represents prioritised absolutely ‘advanced productive forces’ and accompanied the radical liberalisation of the Chinese economy and its partial adaptation to capitalist globalisation. It also opened the door of the CPC to Chinese capitalists, who were growing in number and influence at the turn of the century.5

This did not make the People’s Republic a bourgeois society. Here it is helpful to separate out several questions. Is there capitalism in China? Undoubtedly there is — much, probably most, of the economy is in private hands and the whole is based more on regulated commodity production than on central planning, with a fairly high degree of integration with the world capitalist system. Xi Jinping has spoken of strengthening the role of the state, but this may be contested within the CPC leadership to judge by some of the most recent pronouncements.

Is there a capitalist class in China? That is a more difficult issue. To answer positively one would have to demonstrate a consistent degree of cohesion among China’s capitalists, the formation of class organisations striving to dominate the state, and the development of a bourgeois culture bidding for hegemonic influence. On those grounds the existence of a capitalist class seems currently moot, although the basic material for such a class — that is, owners of the means of production able to appropriate surplus value — is surely extant.

Then, finally, are capitalists in control — are they the ruling class? It is more than probable that Mao Zedong, at least the Mao of his later years, would answer ‘yes’, given that he damned the Soviet Union and the apparatus of the CPC as representing bourgeois power on a very much thinner evidential basis. Obviously, that does not settle the matter. Capitalists seeking political influence are obliged to try to join a communist party, advocating a socialist society. The most recent CPC congress, the 20th, seems to have elected few if any to the party’s central committee.

The most comprehensive attempt, at least outside China, to develop a theoretical basis for commodity production under socialism (something even Stalin acknowledged as unavoidable to some extent) has been undertaken by the late Giovanni Arrighi. He found the possibility of a non-capitalist market economy in the works of Adam Smith as well as Marx.

Arrighi argued that ‘the capitalist character of market-based development is not determined by the presence of capitalist institutions and dispositions but by the relation of state power to capital. Add as many capitalists as you like to a market economy, but unless the state has been subordinated to their class interest, the market economy remains non-capitalist.’6 That is a contentious position, but it arguably corresponds to contemporary Chinese reality.

Elsewhere, Arrighi deepened the point. He argued that equal access to land means that the signal precondition of capitalist development — the separation of direct producers from any control over the means of production — remains unmet. ‘This, of course, does not mean that socialism is alive and well in Communist China, nor that it is the likely outcome of social action. All it means is that, even if socialism has already lost out in China, capitalism, by definition, has not yet won. The social outcome of China’s titanic modernization effort remains indeterminate, and for all we know, socialism and capitalism as understood on the basis of past experience may not be the most useful notions with which to monitor and comprehend the evolving situation [emphasis added].’7

It is worth noting that Arrighi was writing in the first years of this century, before the leadership of Xi Jinping had apparently strengthened the socialist pole in Chinese governance. It is likely he would regard socialism as in better health than it was. However, he focuses attention sharply on the nature of state power and its relation to classes. We will follow him there, but first we should explore the idea that socialism ‘as understood’ cannot be applied willy-nilly and without modification to China in any case.

The spectre of Confucius

If there is a spectre haunting Chinese Marxism, it is of Confucius. Confucianism is deeply embedded in China’s philosophical traditions and the outlook of the Chinese people over many centuries. Space precludes doing anything like justice to its precepts, but it places especial emphasis on social harmony and the idea of the mean. To take one example, Confucius said: ‘If basic essence exceeds cultural refinement it leads to coarseness, but if cultural refinement exceeds basic essence it leads to ostentation.’ The ideal state of things is harmony between two complementary pairs. Confucius held that rulers should use morality and not coercion to govern the state.8 It has both conservative and reformist interpretations, as many broad philosophical systems do (including Hegel’s).

Here we should examine whether socialism, even Marxism, is recalibrated in China on a neo-Confucian basis. Certainly, some in the CPC leadership believe it is so. Classical Marxism derived its method in significant part from Hegel, while revisionist Marxism tended to neo-Kantianism. That Marxism in the 21st century should be enriched by different philosophical traditions is no necessary cause for alarm.

Xi Jinping has been explicit. In 2013, he said that ‘Confucius has had a great influence on the thinking of the civilised progress of humanity, and the sinification of Marxism. To handle China’s affairs well, we must use methods that are consistent with conditions in China… We should think of Confucius’s thought in terms of historical materialism; today’s China is a product of China’s history, and it should adhere to this attitude, adhere to Marxist methods, adopt a Marxist attitude in the study of Confucius.’9

Xi was not breaking entirely new ground. For one thing, ‘Western function serves Chinese essence’ was a popular saying in China in the late 19th century.10 More recently, scholars and officials had been dipping toes in the water of a Marxist- Confucian synthesis for some time. To return briefly to the layered cake of the CPC’s ideological precepts, we come, after the Three Represents, to the Scientific Outlook on Development associated with Xi’s predecessor as party and state leader, Hu Jintao. This is the least substantial of any of the theories inscribed in the CPC constitution, and is more or less tautological. However, Hu also promoted as a code for cadres the ‘eight honours and eight disgraces’, a heavily Confucian concept.11 Gan Yang, a leading new left intellectual, has asserted: ‘In essence, the People’s Republic of China is a Confucian socialist republic. Therein lies the deeper meaning of the Chinese reforms: to further and develop the content of such a republic […].’12

More controversially, Xi has asserted that Mao made use of Confucian ideas. At an obvious level, this cannot be taken entirely as sound currency. Mao once described himself as a mixture of Marx and Qin Shi Huang, the emperor who unified China but also banned Confucian books and buried Confucian scholars alive. The Cultural Revolution was very much a non-Confucian event, and in general Mao preferred struggle to harmony. One of the final mass campaigns launched under his leadership was to ‘criticise Lin Biao and Confucius’. Given that Lin Biao had shortly beforehand plummeted from being the chairman’s chosen successor to dying while fleeing China after the abortion of an alleged attempted coup against Mao, this does not put the great philosopher in very distinguished company.13

Nevertheless, Mao and Confucius shared some common starting points regarding the malleability of human nature and the view that social values arise from social contradictions. The extent to which Mao was a Marxist, as opposed to a leader who liked the idea of Marxism, is a subject of endless debate, but one can see the Confucian admixture in his politics at various points, as well as the influence of other Chinese traditions. When Mao enjoined ‘let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend’, he was sounding more Confucian, or at least rooted in ancient Chinese thinking, than Leninist. Similarly, for Mao dialectics mainly reduced to the unity of opposites, a position quite at odds with Stalin, for example, who at the end of his life believed the concept should be discarded, for propaganda purposes at least. Polemicising with the CPSU at the height of the Sino-Soviet split, the CPC stated that ‘the law of the unity of opposites is the fundamental law of materialist dialectics. It operates everywhere, whether in the natural world, in human society or in human thought.’14 While Confucius was neither a materialist or a dialectician, he would have found the unity of opposites most congenial, and Mao’s elevation of it owes as much to that tradition than to a novel reading of Marxism, which actually holds that unity is relative and conflict permanent.

Today, when describing the socialist future the CPC wants to build, the party speaks of ‘common prosperity’ and ‘harmonious society’. It is easy to see that these are not classical Marxist concepts. As already noted, the class struggle is not central. They are perhaps of limited value to socialists in a capitalist society. But are they alien to any concept of socialism? These ideas would make sense as a description of socialism to very many people. After all, common prosperity (a phrase Mao also used on occasion) and a harmonious society are two things we very much do not have in Britain today. So the Confucianisation of Chinese socialism is not something that should be lightly dismissed as aberrant or irrelevant. It is not a new model, but it does add new ideas to the socialist storehouse.

Even these goals the CPC sees as attainable only over a fairly prolonged period, something quite different from the Soviet perspective of a swift storming to socialism. In this respect, too, the CPC is repackaging positions it has long held in one form or another. In 1963, the CPC stated ‘socialist society covers a very long historical period […] the socialist revolution on the economic front (in the ownership of the means of production) is insufficient by itself and cannot be consolidated. There must also be a thorough socialist revolution on the political and ideological fronts. Here a very long period of time is needed to decide ‘who will win’ in the struggle between socialism and capitalism. Several decades won’t do it; success requires anywhere from one to several centuries […] it is better to prepare for a longer rather than a shorter period of time [emphasis added].’15

Chinese communists have always taken the long view, it seems. Mao had claimed that ‘class struggle, the struggle for production and scientific experiment are the three great revolutionary movements for building a mighty socialist country’16 The first named has been largely discarded by the CPC today, and it is here that the problem arises.17 Confucianism functions in this respect as a negation of class struggle and as a means of binding together in the name of ‘harmony’ a society otherwise divided. This is its less benign aspect.18

China’s own revolutionary history

China has its own revolutionary history too, distinct from matters of philosophy. Obvious landmarks include the Taiping peasant revolutionary war of 1850-65 which aimed at common ownership of the land — not unreasonably described by one historian as ‘as violent and complete a social revolution against an existing order as was ever attempted’19 — and the anti-imperialist risings of the early 20th century looking to end foreign domination of China. These are powerful antecedents of the outlook of the CPC, both under Mao and subsequently.

Reviewing the history of socialism, Xi Jinping identifies six phases — utopian, or pre-Marxist socialism; scientific socialism associated with Marx and Engels; the October Revolution and Lenin; ‘the development of the scientific model’, which refers to Soviet inter-war socialism under Stalin; the ‘exploration’ of socialism by the CPC (the Mao period); and finally the period of ‘reform and opening up’ in China.20

Xi sees this as an integral process. Three points are worth stressing. First, he does not dismiss the history of the Soviet Union, despite its collapse. Indeed, he states that the collapse was itself the result of intense ideological struggle, and that ‘to dismiss the history of the Soviet Union and the history of the CPSU, to dismiss Lenin and Stalin […] is to engage in historical nihilism.’

Second, he does not emphasise the break between the China of Mao and the China of market reform. Instead he underlines the continuities, and emphasises that China today stands on the shoulders of the China of the Mao period. This is quite different from the approach taken by many bourgeois observers of China, not to mention socialists such as John Ross, who write as if China’s socialist history began in 1978, and who juxtapose it to the experience of the Soviet Union.21

Third, Xi’s last two phases of socialism are China-centred. This is not unjustified on the facts. The CPC has remained true to socialism as it understands it, while socialism has disappeared as a system and diminished as a movement throughout the west (Cuba aside), where it was originally expected to triumph. He addresses a reality that socialism’s future now depends largely on what happens in China, the world’s most populous nation.

The connection of the two periods in China’s socialist history is expressed in the Four Cardinal Principles, which involve upholding the socialist path, the people’s democratic dictatorship, the leadership of the CPC, and Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. This the CPC claims to have done, although self-evidently the principles are somewhat question-begging. However, they underline that there is no absolute rupture between CPC strategy today and that in Mao’s time. Mao himself was a flexible and sometimes contradictory thinker whose works can provide fertile justification for varying strategies.

The critical question of the state

So we return to the critical question of the state. As we have seen, Arrighi posited that it is the nature of the state, rather than market relations or private ownership, which determines the character of the social system in China. This mirrors in a way the Maoist proposition of the 1960s that the overwhelming prevalence of public ownership in the Soviet Union and elsewhere did not guarantee the state’s class character, since a ‘revisionist bourgeoisie’ had seized power. This position may be judged plainly wrong, but its ascribing of a determining degree of autonomy to political functions at the state level may be fruitful. In Britain, we can recall very high levels of public ownership of industry and other activities in the 1960s and 1970s and no socialism at all, since these were subordinated to commodity relations and the dynamics of capital accumulation.

The state controls many of the biggest corporations in China across the basic sectors of the economy, and it further regulates the economy as a whole. Economic actors are ultimately subject to state direction, as they are not in a capitalist society. Land is ultimately owned by public collectives. State regulation and management of economic aggregates have clearly been critical to ensuring the decades of fast economic growth and the avoidance so far of the crises of over-accumulation that mark capitalist systems. But what does this tell us?

The formulations of the CPC point in multiple directions. Let us cite the report by Xi to the 19th CPC congress: ‘China is a socialist country of people’s democratic dictatorship under the leadership of the working class based on an alliance of workers and farmers; it is a country where all power of the state belongs to the people.’22 Many bases are touched here. The first formulation, ‘people’s democratic dictatorship’, generally refers to a class alliance of the working class, peasantry, petty-bourgeoisie, intelligentsia and, in some readings, the national (non-comprador) bourgeoisie. This draws on Mao’s ‘Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People’, written in the aftermath of the CPSU 20th congress and the attempted counter-revolution in Hungary. This is how he explained the presence of capitalists in China’s prevailing class alliance:

The contradiction between the national bourgeoisie and the working class is one between exploiter and exploited, and is by nature antagonistic. But in the concrete conditions of China, this antagonistic contradiction between the two classes, if properly handled, can be transformed into a non-antagonistic one and be resolved by peaceful methods. However, the contradiction between the working class and the national bourgeoisie will change into a contradiction between ourselves and the enemy if we do not handle it properly and do not follow the policy of uniting with, criticizing and educating the national bourgeoisie, or if the national bourgeoisie does not accept this policy of ours.23

Of course, in 1957 China was completing the elimination of private ownership of industry, even if leaving the same managers often in charge, whereas today private ownership has been ‘brought back from the dead’, the better to develop China’s economy and national strength, and plays a very significant part in the overall economy.

To say it is ‘under the leadership of the working class’ was again a common post- war formulation in the socialist countries, and recalls the statement by leaders of those countries in the late 1940s to the effect that ‘people’s democracy fulfils the functions of the dictatorship of the proletariat’. And indeed the distinctions between the eastern European socialist countries under people’s democracy and the USSR under Soviet power were second order.

Then we have Xi’s ‘alliance of workers and farmers’ on which the ‘leadership of working class is based’, which privileges the alliance with the peasantry. With variations this is a very old formulation, dating back to the Russian revolutions of the early 20th century. It is unsurprising that the peasants are so privileged, given that China remains a heavily agrarian society, albeit rapidly urbanising, and political power across much of its territory must rest on the support, or at least acquiescence, of the peasantry. So far, the bourgeoisie in China, if there be such, has not made an appearance.

Finally, Xi appears to negate all of the foregoing by declaring ‘all power of the state belongs to the people [emphasis added]’ — an undifferentiated people, without class distinction. Here we are more or less back to Khrushchev. Superficially, this is all a bit of a muddle, or rather a stew in which almost everyone can find something agreeable. However, that is hardly a satisfactory assessment.

Surely the key lies in the fact that China is in a prolonged period of transition to a matured socialism and beyond that communism, and that throughout this period, as everyone from Marx to Mao accepted, the class struggle will persist. It surfaces at Foxconn, in the struggles against corruption, in disputes over land use and in a thousand other mass struggles occurring every month. Its persistence will arise both from the internal dynamics of China’s heterogeneous development and from the global context which, at present, is not one of the general transition to socialism. However, the Chinese party does not give proper political weight to the existence of this struggle, even as it addresses its manifestations in practice. This may be down to a desire to distance from Mao’s fetishisation of class struggle and often misdirected waging of it, or it may be simply what all governments tend to do — deny or downplay the existence of internal contradictions. Nevertheless, the CPC can only reflect the heterogeneity of Chinese society, even as it avoids generalising from the consequences.

In practice, the Chinese state does not act as the compliant servant of capital accumulation. To take one powerful example, consider its response to the Covid pandemic. Whatever subsequent problems arose, at the outset and for years after its priority was clearly saving lives by all possible measures, regardless of the economic consequences. Needless to say, this was quite different from the conduct of the public power in Britain or the US. And when significant sections of the Chinese people rebelled against continuing restrictions, the government relaxed its measures. But the decisive pressure came from below, not from any bourgeoisie. However, Mao’s insistence on the possibilities of contradictions arising between the people and the party leadership does not seem entirely otiose.

Conclusions

It is idle to pretend that any of these reflections can be definitive. What is undeniable is that the future of socialism in the world depends very heavily on developments in China and on the leadership of its communist party. As Xi has said, without China socialism risked being pushed entirely to the margins of world affairs after 1991. It is welcome that Xi also stresses the socialist essence of China’s state, with all the contradictions and equivocations, and likewise emphasises the ‘final goal’ of communism.

That alone makes the world ideologically multipolar, and not just in terms of the distribution of power which China has also altered irreversibly. It is not the zero-sum ideological confrontation of the Soviet period, based on the assumption of an international revolutionary process unfolding inexorably in the direction of world socialism. But it disputes the hegemony of the capitalist system and of neoliberal centrism. This is a service to humanity which deserves support. Again, this need not be the unequivocal alignment of communists with the Soviet Union for generations. China does not insist on recognition of its model, not does it acquiesce in the inevitability of confrontation with imperialism. But the new cold war being initiated by embittered, recalcitrant and declining imperialist powers must be opposed. It is against the interests of the British people on multiple fronts, and in fighting against it we are serving the interests not of the Chinese state but of working people here.

As for the rest, we can only approach Chinese society in the spirit of Mao’s formulation that ‘man’s knowledge of a particular process at any given stage of development is only relative truth. The sum total of innumerable relative truths constitutes absolute truth.24

Notes

- I am most grateful to Keith Bennett and Jenny Clegg for many insightful comments on the original draft of this article and for seeing me right on various points. They are of course not responsible for any opinions or remaining errors.

- See, for example, Zhang Chunqiao, ‘Do Away with the Ideology of Bourgeois Right’, People’s Daily, 13 October 1958. Zhang was later a member of the notorious ‘Gang of Four’.

- Wu Guoyou and Ding Xuemei, trans. Sun Li and Shelly Bryant, An Ideological History of the Communist Party of China: Volume 3 (Royal Collins, 2020), p. 7.

- Constitution of the Communist Party of China, in Documents of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (People’s Publishing House, 2017), p. 99.

- It is not unprecedented for communist parties to include capitalists (even large ones) in their membership. The CPGB did at one point. But there are no exact parallels here.

- Giovanni Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (Verso, 2007), pp. 331- 32.

- Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing, p. 24.

- Yan Wenming, ed., The History of Chinese Civilizaton: Volume 1 (Peking University Press, 2006), pp. 23, 486.

- François Bougon, Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping (Hurst & Co., 2017), p. 145.

- Rebecca E. Karl, China’s Revolutions in the Modern World: A Brief Interpretive History (Verso, 2020), p. 23.

- ‘Honour those who love the motherland, shame on those who harm the motherland’, and so on, through values such as hard work, trustworthiness and plain living.

- Bougon, Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping, p. 151.

- The campaign as it developed actually targeted the premier Zhou Enlai, and may have reflected the Gang of Four’s aims as much or more than those of Mao, who was nevertheless still chairman of the CPC.

- Communist Party of China, ‘On Khrushchov’s Phoney Communism’, in The Polemic on the General Line of the International Communist Movement (1964; Red Star Press, 1976), p. 471. For Stalin’s view, see Revolutionary Democracy 21.1 (April 2015), p. 159.

- CPC, ‘On Khrushchov’s Phoney Communism’, pp. 471-72.

- CPC, ‘On Khrushchov’s Phoney Communism’, pp. 476-77.

- The preamble to the Constitution of the CPC makes the following solitary reference to class struggle in the course of an 18-page ideological exposition: ‘Owing to both domestic factors and international influences, a certain amount of class struggle will continue to exist for a long time to come, and under certain circumstances may even grow more pronounced, however, it is no longer the principal contradiction’ (CPC, Documents of the 19th National Congress, p. 104).

- See Karl, China’s Revolutions in the Modern World, p. 192: ‘Harmony is an old Confucian value; nothing could be further from class struggle’.

- Franz H. Michael, The Taiping Rebellion: Volume 1 (University of Washington Press, 1966), p. vii.

- Bougon, Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping, p. 87.

- See John Ross, China’s Great Road: Lessons for Marxist Theory and Socialist Practices (Praxis Press, 2021). Ross also confuses bourgeois right with public ownership of the means of production in considering the nature of socialism.

- CPC, Documents of the 19th National Congress, p. 43.

- Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung: Volume 5 (Pergamon Press, 1977), p. 386.

- Mao Zedong, ‘On Practice’, in Mao on Practice and Contradiction (Verso, 2007), p. 64.

I am from Vancouver,Canada and i wanted to say that Communism like Capitalism and Feudalism before that is something that happens gradually. It took Feudalism several hundred years before it was firmly established and the same with Capitalism.

When people say that we had Socialism and it didn’t work they got no idea what they are talking about.We are still living in a Capitalist Society and Gradually things are changing towards a Socialist Society. It takes time and the world don’t change within a few years.

People needs to study these things and then they won’t ask if people are living in a Capitalist Country or a Socialist Country.