In this detailed article, which was originally published by The Real News Network, Ju-Hyun Park, the network’s engagement editor, analyses the implications for regional peace, security and economics of the tripartite summit between the United States, Japan and South Korea, that US President Joe Biden hosted at Camp David in August, and relates them to the intensified crackdown on the labour movement and wider sections of civil society since a new conservative administration took office in South Korea.

According to Park, this budding tripartite alliance is a “dream come true for Washington in the New Cold War. And it wouldn’t be happening without South Korean President Yoon’s [Yoon Suk Yeol] war on labour and the opposition.”

Noting that, at Camp David, “for the first time, South Korea, Japan, and the US pledged to share data on North Korean missiles, coordinate joint military responses to threats in the region, and host a new annual trilateral military exercise,” Park explains: “These outcomes indicate a realignment of forces in East Asia that significantly raises the risks of potential major power conflict with China… The Camp David summit is a sure step towards achieving one of Washington’s long-standing goals: establishing an Asian equivalent to NATO as a bulwark to protect US interests in the Pacific.”

Roping South Korea into an alliance with Japan has been an aim of US policymakers since the Korean War (1950-53), but consummating it has proved elusive, both because of the bitter legacy of Japanese colonial rule on the Korean peninsula and latterly South Korea’s burgeoning and mutually beneficial economic relationship with China:

“China overtook the US as South Korea’s primary trade partner almost 20 years ago, and South Korea’s largest corporations depend on China for labour, production, and markets. While South Korea’s capitalists also benefit from the US military occupation of the peninsula, there are few benefits to them in picking sides in a zero-sum conflict between the US and China.”

Biden’s apparent success, therefore, in binding the two powers together in a joint embrace with the United States may been seen as a victory for deft diplomacy, but “there is another cause that deserves significantly more credit: For the past year, current South Korean President Yoon Seok Yeol has waged a ruthless war on the sections of South Korean civil society standing in the way of Washington’s agenda, attacking labour, peace groups, and the general public.”

Yoon’s principal target has been South Korea’s militant labour movement. In January this year, hundreds of police officers raided the offices of multiple progressive organisations, including the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), which represents over two million workers.

Yoon has also overseen a drastic escalation in the frequency and intensity of joint military exercises between South Korea and the US, with more than 20 planned for this year alone.

According to Park:

“Labour repression within South Korea also plays a significant role in facilitating Washington’s aims to technologically and economically isolate China… The war on Chinese tech goes beyond targeting individual Chinese conglomerates. Under Biden, a strategy has slowly taken shape to attempt to bring as much high-tech production back to the US as possible while simultaneously taking measures to exclude China from existing international supply chains that rely heavily on production in Taiwan and South Korea. Two of Biden’s biggest legislative wins, the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act, contain provisions that effectively force South Korean companies to abandon their investments in China in favour of building electric vehicle and semiconductor factories in the US. South Korean EV battery makers have already committed $13 billion to build new plants and expand existing ones in seven US states.

“This has all come at a steep cost to South Korea. South Korean technology exports to the Chinese market plummeted in the wake of the CHIPS and Inflation Reduction Acts. From 2022 until June 2023, South Korea suffered the most severe trade deficit in its history, haemorrhaging some $47.5 billion in 2022 alone. By far, the leading cause of this deficit was the sudden reversal in trade with China.

“Squeezed between rising inflation and spiralling economic prospects, South Korea’s workers are bearing the brunt of this economic realignment. At the same time, the Yoon government is scrambling to find some way to reverse its poor economic performance without making concessions to workers. Hence, Yoon’s war on trade unions – the only vehicles available for the working class to organise independently and fight back… South Korean labour is one of the only organised obstacles within the US-led bloc to Washington’s economic offensive against China. Crushing the unions means clearing the way for the unhindered reengineering of South Korea’s economy in Washington’s vision.”

Whilst noting that Chinese President Xi Jinping seems determined to maintain cordial relations with South Korea, if at all possible, Park adds that analysts have also warned of the possibility that the trilateral alliance could be used as a mechanism to draw South Korean forces into US wars abroad – including in the Taiwan Strait.

Park also explains that the tightening of a US-led hegemonic bloc in the Pacific inevitably comes up against the law that every action has a reaction, in this case in terms of further consolidating the ties between Pyongyang, Moscow and Beijing:

“North Korea, isolated and encircled for so long, now has a wide and reliable rearguard of support in Moscow and Beijing. As the centre of economic gravity pivots towards China, opportunities for North Korea’s advancement will only proliferate.”

While largely unnoticed by the US public, the trilateral summit between Japan, South Korea, and the US that took place at Camp David this August sent shockwaves throughout East Asia.

US President Joe Biden, South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio punctuated the end of the three-day summit by releasing a joint declaration rife with the kinds of diplomatic ambiguities and appeals to vague principles typical of this sort of affair. The three leaders pledged their support for a “free and open Indo-Pacific,” for an international “rules-based order,” and for “peace and stability” around the world. But, of course, the historic significance of the summit had less to do with the rhetoric and more to do with the concrete commitments made by the three governments.

The Pacific today looks a lot like Europe on the eve of the First World War—a hotbed of military powers sharply divided into opposing blocs driven by irreconcilable interests, ready to be pulled into war at a moment’s notice.

For the first time, South Korea, Japan, and the US pledged to share data on North Korean missiles, coordinate joint military responses to threats in the region, and host a new annual trilateral military exercise.

These outcomes indicate a realignment of forces in East Asia that significantly raises the risks of potential major power conflict with China. Japan and South Korea have been individual allies of the US for decades—but the three have never before been part of a shared military structure. Now, with an agreed-upon “commitment to consult,” tighter military integration and coordination between the three countries than ever before is assured.

While there is no treaty to bind this budding alliance together yet, the unprecedented “trilateral security cooperation” born from the Camp David summit is a sure step towards achieving one of Washington’s long-standing goals: establishing an Asian equivalent to NATO as a bulwark to protect US interests in the Pacific. The result, which is already manifesting, is a much more divided and hostile region than existed before—where the possibility of great power conflict between nuclear states seems to be more a matter of time than a mere hypothetical.

WRANGLING SOUTH KOREA

Roping South Korea into an alliance with Japan has been an aim of US policymakers since the Korean War, when then-Secretary of State Dean Acheson sought to weld South Korea and Japan together into an economic bloc that could revive Japanese industry post-World War II and ward off communist influence in Asia. In recent years, however, the rise of China as an economic powerhouse, coupled with the nuclearization of North Korea, has brought renewed urgency to this long-sought objective.

For years, Seoul proved to be a slippery fish in Washington’s net. Yoon’s predecessor, Moon Jae-In, delicately navigated support for US military expansion in Korea without making ironclad commitments to insert South Korea into an anti-China bloc.

The reasons for South Korea’s previous ambiguity lay in a divergence of interests between Seoul and Washington in light of a rapidly changing world. China overtook the US as South Korea’s primary trade partner almost 20 years ago, and South Korea’s largest corporations depend on China for labor, production, and markets. While South Korea’s capitalists also benefit from the US military occupation of the peninsula, there are few benefits to them in picking sides in a zero-sum conflict between the US and China.

This is all rather inconvenient for those in Washington intent on preserving US hegemony indefinitely. South Korea is not only geostrategically important in a conflict against China—it also has the largest military of any US ally in the region, and is also a crucial producer of advanced technologies which US corporations and the Pentagon depend on. To put it simply, the US needs South Korea to succeed in containing China far more than South Korea needs to participate in this conflict.

Then there’s the other, far thornier issue of Japan’s 35-year colonization of Korea and the deep imprint it has left—and continues to have—on Korea. Japan has yet to fully acknowledge, apologize for, or offer satisfactory compensation for its many colonial crimes against the Korean people. This matter remains an open wound on the Korean psyche, and a thorn in the side of Tokyo and Washington.

The litany of Japanese atrocities in Korea are too many to name here, but the most prominent issue at the moment concerns Japan’s forced conscriptions of Koreans during WWII. From 1939 to 1945, Japan forcibly conscripted hundreds of thousands of Koreans to fight its wars, and mobilized more than 3 million Koreans as forced laborers throughout its empire. Among the most heinous and best known of these crimes was the conscription of an estimated 200,000 Korean women into sexual slavery for Japan’s military—a program euphemistically known as the “comfort women” system.

In 2018, the South Korean Supreme Court ordered Japanese conglomerate Mitsubishi, which profited from wartime forced labor, to pay reparations to their surviving victims. This incident set off a diplomatic row that escalated to the level of a trade dispute that lasted for years.

For Washington, the renewed push to force Japan to address and atone for these historical injustices could not have come at a more inconvenient time. Just a year before, in 2017, India, Australia, Japan, and the US had revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the Quad—a military alliance intended to serve as the main axis of a new anti-China bloc.

The Trump administration was keen to rope South Korea in as a fifth member of the Quad, but this goal never materialized. Entering any kind of explicit alliance with Japan was, and still is, politically toxic in South Korea. Moreover, as the world enters a new era where the US is losing its footing as the globe’s preeminent military and economic power, South Korea, among other nations, was quite sensibly reading the room and attempting to hedge its bets.

Upon entering office, Biden’s administration set achieving a trilateral partnership between the US, Japan, and South Korea as a high priority, seeking to accomplish what its predecessor could not. The Camp David summit represents a major step towards achieving this goal. While the White House and its cheerleaders have already claimed this as a victory for deft diplomacy, there is another cause that deserves significantly more credit: For the past year, current South Korean President Yoon Seok Yeol has waged a ruthless war on the sections of South Korean civil society standing in the way of Washington’s agenda, attacking labor, peace groups, and the general public.

ENTER YOON SEOK YEOL

Despite less than 18 months in office, Yoon has earned the dubious distinction of being South Korea’s least popular head of state ever—not to mention one of the most maligned leaders in the world. His administration has been pilloried by civil society groups and the main opposition Democratic Party for its corruption and ineptitude, while simultaneously characterized as a “prosecutor’s dictatorship” where escalating abuses of executive power are interpreted by many as signs of backsliding towards South Korea’s days of autocratic rule.

Domestically, the Yoon administration has declared war against its political enemies, particularly against the labor movement. In January of this year, hundreds of police officers raided the offices of multiple progressive organizations, including the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, which represents over 2 million workers.

Yoon’s domestic crackdown isn’t taking place in a vacuum separate from the formation of the trilateral alliance. These repressive measures are the necessary internal complement to an international agenda primarily determined not in Seoul, but in Washington.

Wielding trumped-up charges ranging from racketeering to spying on behalf of North Korea, the Yoon administration has weaponized law enforcement to continue its crackdown on labor and progressive organizers throughout this year. Over 1,000 members of the Korean Construction Workers Union alone are currently under federal investigation, and more than 30 are now in jail. One local KCWU leader, Yang Hoe-dong, died by self-immolation in protest of these charges—transforming himself into a martyr for the movement to rally around.

It’s not just labor unions that have found themselves in Yoon’s crosshairs. The 6.15 Committee has also been the target of official persecution. Originally founded in 2000, the 6.15 Committee has chapters on both sides of the Korean peninsula and overseas that work towards building support for Korean peace and reunification through people-to-people exchanges. At the same time that the KCTU’s offices were raided, members of the 6.15 Committee in Jeju province were arrested on espionage charges. The evidence? They had previously hosted a public screening of a North Korean film.

Perhaps most brazenly, the Yoon administration has also escalated attacks on the media. Two news outlets, Newstapa and the Joongang Tongyang Broadcasting Company, were raided by prosecutors on Sept. 14, 2023, for publishing a story in 2022 spotlighting Yoon’s alleged participation in an illegal loan scheme. Press freedom has never stood on firm ground in South Korea, even after the supposed era of “democratization” in the 1990s. Ousted former President Park Geun-hye notoriously maintained a blacklist banning thousands of artists considered unfriendly to her government. Yet no other president since the days of military dictatorship ever dared to use state security forces against a media office, until Yoon.

Yoon’s domestic crackdown isn’t taking place in a vacuum separate from the formation of the trilateral alliance. These repressive measures are the necessary internal complement to an international agenda primarily determined not in Seoul, but in Washington.

OLD AUTOCRACY, NEW COLD WAR

As president, Yoon has overseen several dramatic changes in South Korean foreign policy that benefit US interests and require the repression of internal dissent to achieve: scuttling relations with North Korea, joining US attempts to technologically isolate China, and reconciling with Japan to clear the way for the Camp David summit.

Since coming into office, Yoon has overseen a drastic escalation in the frequency and intensity of joint military exercises between South Korea and the US. These military exercises began in the 1970s as annual affairs—now, there are more than 20 planned for 2023 alone. These war drills routinely rehearse invasions of North Korea within miles of the DMZ, the de facto border that has divided Korea since the 1953 armistice.

The KCTU and other labor groups have provided some of the most stalwart opposition to these war games. Last year, in response to the Ulchi Freedom Shield exercises, the KCTU joined hands with the more moderate Federation of Korean Trade Unions to deliver a joint statement denouncing war maneuvers—a statement that was, significantly, also signed by their union umbrella counterpart in North Korea.

Predictably, Yoon and Biden’s acts of aggression have prompted parallel North Korean shows of force, which then provide the pretext for Washington, Seoul, and, increasingly, Tokyo to escalate in turn. The Biden administration deployed two US nuclear submarines to Korea for the first time in 40 years this summer, and the US and South Korea warned in a joint statement that “Any nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its allies is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime.”

Labor repression within South Korea also plays a significant role in facilitating Washington’s aims to technologically and economically isolate China, a crucial pillar of National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan’s “New Washington Consensus.” Here, the intersection of technological and military power are key. US domination of tech patents is one of the pillars of its premiere position in the global economy—a position it can only hold so long as Chinese attempts to develop domestic tech production capacity are foiled.

Maintaining US dominance of the tech market also has more obvious military implications for Washington, which depends on semiconductors produced in South Korea and Taiwan to operate its weapons of mass destruction. Gregory C. Allen, an analyst with the hawkish Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, describes Washington’s tech offensive against China as “actively strangling large segments of the Chinese technology industry—strangling with an intent to kill.”

Attempts to “strangle” Chinese tech have escalated sharply under the Trump and Biden administrations. Two of the clearest and highest-profile examples of this have been US attempts to sanction Huawei, going as far as to coordinate the arrest of the company’s CFO during a visit to Canada, as well as the push to ban TikTok, which culminated in a bizarre and ridiculous Senate hearing earlier this year.

But the war on Chinese tech goes beyond targeting individual Chinese conglomerates. Under Biden, a strategy has slowly taken shape to attempt to bring as much high tech production back to the US as possible while simultaneously taking measures to exclude China from existing international supply chains that rely heavily on production in Taiwan and South Korea. Two of Biden’s biggest legislative wins, the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act, contain provisions that effectively force South Korean companies to abandon their investments in China in favor of building electric vehicle and semiconductor factories in the US. South Korean EV battery makers have already committed $13 billion to build new plants and expand existing ones in seven US states.

This has all come at a steep cost to South Korea. South Korean technology exports to the Chinese market plummeted in the wake of the CHIPS and Inflation Reduction Acts. From 2022 until June 2023, South Korea suffered the most severe trade deficit in its history, hemorrhaging some $47.5 billion in 2022 alone. By far, the leading cause of this deficit was the sudden reversal in trade with China.

Squeezed between rising inflation and spiraling economic prospects, South Korea’s workers are bearing the brunt of this economic realignment. At the same time, the Yoon government is scrambling to find some way to reverse its poor economic performance without making concessions to workers. Hence, Yoon’s war on trade unions—the only vehicles available for the working class to organize independently and fight back. As President Yoon himself put it, the crackdown on unions is necessary “so that corporate value can rise, capital markets can develop, and many jobs can be created.” South Korean labor is one of the only organized obstacles within the US-led bloc to Washington’s economic offensive against China. Crushing the unions means clearing the way for the unhindered reengineering of South Korea’s economy in Washington’s vision.

Amid this political and economic chaos, Yoon was able to broker a new understanding with Tokyo that put an end to years of diplomatic and economic clashes. In a move many critics described as unconstitutional, the Yoon administration unilaterally modified the 2018 Supreme Court decision ordering restitution from Japanese companies for Korean survivors of wartime forced labor. Instead, the survivors will now be compensated from a fund paid into by South Korean corporations, letting their Japanese counterparts off the hook. Despite being opposed by some 60% of South Koreans, this arrangement allowed for a thaw in Seoul and Tokyo’s relations, which, in turn, set the stage for the summit at Camp David this August.

Analysts have also warned of the possibility that the trilateral alliance could be used as a mechanism to draw South Korean forces into US wars abroad—including in the Taiwan Strait.

The specter of North Korean nuclearization was presented as the primary justification for the Camp David summit and the resulting trilateral security cooperation alliance. But the outcomes of Camp David were not exclusively military in nature. Japan and South Korea also pledged to share data on critical supply chains with the US.

Domestically, Yoon’s participation in the Camp David Summit was widely lambasted as a betrayal of South Korea’s interests. The summit has not only heightened tensions on the Korean peninsula; it has also done significant damage to South Korean relations with Russia and China, although China’s Xi Jinping seems determined to maintain cordial relations. Analysts have also warned of the possibility that the trilateral alliance could be used as a mechanism to draw South Korean forces into US wars abroad—including in the Taiwan Strait.

The Camp David Summit has only brought more darkness to the political climate in South Korea. Days before he left for the US, Yoon gave a national address for Liberation Day, which marks the anniversary of the end of Japanese colonial rule in Korea. Rather than offer reflections on the human toll of the colonial period or the legacy of the Korean independence movement, Yoon fixated on a different target: “The forces of communist totalitarianism have always disguised themselves as democracy activists, human rights advocates, or progressive activists while engaging in despicable and unethical tactics and false propaganda,” he said. “We must never succumb to the forces of communist totalitarianism.”

In South Korea, anticommunism and state repression have gone hand-in-hand since the “Republic of Korea” was first established in a widely opposed, US-sponsored election process in 1948. Before the Korean War officially began in 1950, a mass uprising on the island of Jeju against Korea’s division ended in the slaughter of between 30,000 and 60,000 people. In the early days of the Korean War itself, the South Korean government massacred between 100,000 and 200,000 political dissidents that had previously been forced to register in the so-called National Guidance League.

Throughout the long night of South Korea’s military dictatorships, which lasted from the end of WWII to the 1990s, strikes were broken, activists tortured and disappeared, and families of the massacred and vanished were silenced and surveilled in the name of suppressing the communist threat. When the city of Gwangju took up arms in 1980 to demand democracy and appealed to the US to intervene, President Jimmy Carter greenlit the deployment of South Korean paratroopers from the DMZ to butcher as many as 2,000 of the city’s residents. In the aftermath, the Chun Doo Hwan regime blamed the events in Gwangju on North Korean infiltrators and communists.

For now, the Yoon administration has limited the scale and brutality of its crackdown to incarcerations and prosecutorial witch hunts. But the echoes of Korea’s recent history leave many wondering if, or when, the bloodletting will return. For its part, the Biden administration has followed in the footsteps of every previous administration by refusing to acknowledge the political repression unfolding under Yoon’s South Korea. Corporate media, in turn, has largely ignored the outcry against the Camp David summit by South Koreans themselves.

DIVIDING KOREA, DIVIDING THE PACIFIC

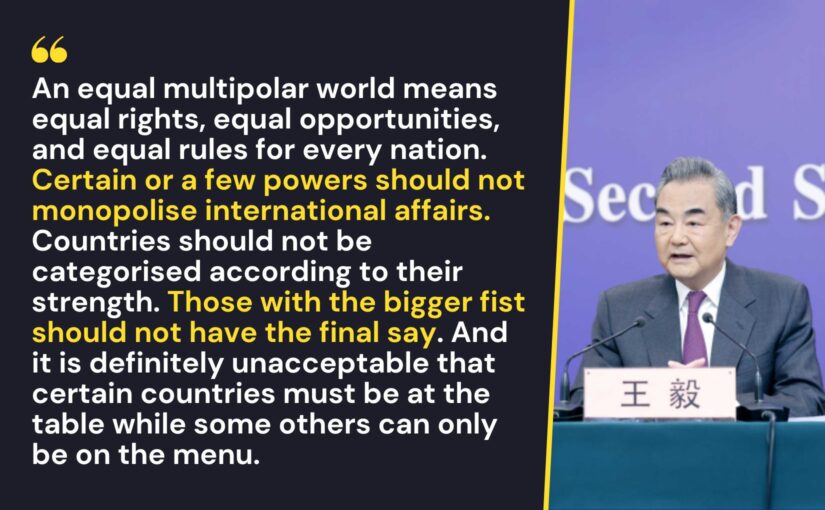

The joint statement delivered at Camp David cast the new US-Japan-South Korean axis in terms of a partnership based on a mutual desire for global peace and prosperity. But the immediate consequences of the summit strongly indicate that things are, in fact, moving in the opposite direction.

Rather than deescalating military tensions and breaking down barriers to international cooperation, the Camp David Summit signals an escalation of military threats coinciding with the tightening of a US-led hegemonic bloc in the Pacific. Every action has a reaction, and the reaction here is coming in the form of a consolidated counter-bloc between Pyongyang, Moscow, and Beijing.

The reestablishment of cooperative relations between North Korea, China, and Russia has been a long time coming. Relations between the three countries turned cold after the destruction of the Soviet Union. For decades, Russia and China acquiesced to UN Security Council sanctions against North Korea—something which they no longer are willing to abide.

In recent years, Beijing and Moscow have increasingly turned to each other, and to Pyongyang, as fellow targets of US sanctions, military encirclement, and propaganda. For all its bombastic proclamations about protecting peace and freedom around the world, Washington has created the conditions for a new unity of interests to emerge among those states it names as its enemies.

Pyongyang, Beijing, and Moscow were all united in their alarm and rejection of the Camp David Summit—and not without reason. All three countries were explicitly named in the Camp David Principles and Joint Statement as problems to be managed by the self-appointed triumvirate. China and Russia also share borders with Korea, which will be the primary site of military escalation by Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul. Beijing and Pyongyang swiftly denounced the new bloc. Moscow even suggested the start of trilateral naval exercises between the three countries as a counter to US-led military maneuvers.

On Sept. 12, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un boarded an armored train for the Russian Far East in his first foreign visit as head of state since 2019. In a meeting with Vladimir Putin, Kim expressed his government’s full support for Russia in its conflict against NATO, and received pledges to assist with developing space technologies from Moscow.

For the time being, the two Korean states have aligned with opposing global interests. The possibility of reunification and reconciliation, which seemed so tantalizingly close just a few years before, now appears to be far out of reach. Yet even as the currents of world politics pull Korea apart once again, opportunities for a different future remain.

South Korea, which ascended economically for decades on Washington’s coattails, now finds itself on the side of a declining power. Already, Seoul is being forced to choose between its objective interests in closer ties with its neighbors and Washington’s contravening political preferences. The result appears to be a declining trend in South Korea’s fortunes—something key stakeholders in the country may not tolerate forever.

North Korea, isolated and encircled for so long, now has a wide and reliable rearguard of support in Moscow and Beijing. As the center of economic gravity pivots towards China, opportunities for North Korea’s advancement will only proliferate. The unintended result in the not-too-distant future could well be two Koreas that can stand on truly equal footing and finally become one, ending the division of Korea and the centrality of that division in manufacturing regional conflict.

But perhaps such predictions are too optimistic for the present moment. After all, Korea must survive intact for such a future to be possible. The Pacific today looks a lot like Europe on the eve of the First World War—a hotbed of military powers sharply divided into opposing blocs driven by irreconcilable interests, ready to be pulled into war at a moment’s notice. That war was so cataclysmic that for a generation it could only be remembered as The Great War. The war to come will be even more vicious, and so far, it’s being served to us with a smile.