We are pleased to republish below an article by Jenny Clegg for the Morning Star explaining how China’s democracy works, focusing on the National People’s Congress (NPC), which met in early March.

Jenny points out that, while the Western media insists on disparaging the NPC as a “rubber stamp” parliament, it is in fact a key institution in China’s system of people’s democracy. While this system of democracy is different from Western “liberal” democracy, it is nonetheless a legitimate political form seeking to empower and represent the people.

Jenny explains that laws passed by the NPC “undergo a prior long and arduous process of deliberation, consultation and revision to ensure disagreements and differences are addressed and ultimately consensus is reached”. The People’s Congress system “involves nearly 3 million deputies, 95 per cent at township and county levels; non-Communist Party members make up at least a third of these. Villages are self-administered — elections, introduced in 1998, are conducted every 3-5 years”.

The article notes that NPC deputies “are expected to serve as ‘a bridge between party, state and people,’ spending the bulk of the recess period conducting research, carrying out inspections and extensive consultations, and then formulating proposals to be subject to rigorous debate and revision.” Trade unions, women’s and other mass organisations are consulted on all relevant pieces of legislation, and those laws that particularly concern the immediate interests of the wider public are put out in draft form for public debate.

Importantly, at a time when democratic processes are under attack in the West, Jenny observes that “the modernisation of socialist democracy in China is a work in progress”, and is being constantly reviewed and updated in order to better serve the people and encourage mass participation.

Jenny is an independent writer and researcher, specialising in China’s development and international role; and a former Senior Lecturer in Asia Pacific Studies at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLAN). She is the author of China’s Global Strategy: towards a multipolar world (Pluto Press, 2009) and Storming the Heavens – Peasants and Revolution in China, 1925-1949 – from a Marxist perspective (Manifesto Press, 2024).

China’s nearly 3,000-member National People’s Congress (NPC) has just gathered for its annual meeting in Beijing. Western mainstream media continually disparages China’s main legislature as a “rubber stamp parliament” — mindlessly repeating the phrase to numb readers’ minds to any thought other than that China must be a dictatorship.

That there are other forms of democracy — the idea of democratic centralism, deliberative democracy, has been around for over 100 years — the mainstream media cannot comprehend.

True, the NPC only meets for two weeks a year and never seems to reject any piece of legislation put before it. However, the reason why laws are passed unanimously is that they undergo a prior long and arduous process of deliberation, consultation and revision to ensure disagreements and differences are addressed and ultimately consensus is reached.

Borrowed from the USSR in 1954 alongside the systems of public ownership and five-year plans, the people’s congress structure operates through tiers reaching from townships up through counties and provinces to the national level. It involves nearly 3 million deputies, 95 per cent at township and county levels; non-Communist Party members make up at least a third of these. Villages are self-administered — elections, introduced in 1998, are conducted every 3-5 years.

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee — the other part of the “two sessions” — forms parallel tiers serving in an advisory and consultative capacity. It includes the eight democratic parties which originally took part in China’s revolution and today continue to represent intellectuals and professionals.

Nominations for congress deputies are encouraged from workplaces, rural and urban communities, trade unions, women’s and other mass organisations. Front-line workers, farmers and national minorities are represented right up to the national level under a quota system. The party and higher state levels oversee elections, approving candidates both to ensure inclusivity across diversified social groups and to vouch for candidate competence.

However, the system relies not simply on elections — it also involves consultations, decision-making, management, and oversight. In line with the Marxist perspective, and contrary to the liberal myth of the separation of powers, executive, legislative and judiciary work closely together, with the party formulating views to be re-examined and substantiated through the people’s congresses, and then transformed into legislation forming the basis for the governance system.

Deputies are expected to serve as “a bridge between party, state and people,” spending the bulk of the recess period conducting research, carrying out inspections and extensive consultations, and then formulating proposals to be subject to rigorous debate and revision.

After ceasing to function during the Cultural Revolution, the NPC has passed an enormous raft of legislation since 1978 — by international standards, the laws are generally progressive. To ensure laws are implemented, congress deputies are also expected to keep contact with courts and supervisory institutions.

So that laws are practicable and feasible, as well as in accord with and understood by the wider public, consultations take place with trade unions, women’s and other mass organisations — as well as with experts and the democratic parties. Laws that particularly concern the immediate interests of the wider public — such as women’s and labour rights — are put out in draft form for public debate and comment: the draft 14th five-year plan received one million suggestions from the public within two weeks.

In 2016 a number of urban districts were selected to serve as basic legislative contact points for the NPC standing committee to increase participation in policy-making. These grassroots units use street-level and “courtyard” forums, with public hearings held in districts, industries, small and medium-sized enterprises as well as government offices, to collect opinions and gather suggestions for legislation and improvements of draft laws.

The Hongqiao Street grassroots legislative unit in Shanghai, for example, held more than 50 forums for legislative proposals in 2020, its first year of existence — more than 1,000 people participated in the call for comments and finally 366 legislative amendments and recommendations were submitted of which 66 were adopted by the Shanghai Municipal People’s Congress. The Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests (Revised Draft) drew considerable public interest, receiving the most comments and suggestions, backed by a degree of NGO lobbying.

The popular “12345 hotline” set up in Chinese cities serves as a mechanism not only for citizens to seek advice, but also to express complaints and criticise the work of local government, helping to highlight areas where both regulations and cadres’ performance required improvement.

In 2018, the NPC also set up a National Supervisory Commission to strengthen Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption system. And in 2021, in a major step forward, a new law was passed to give citizens the right to criticise and make suggestions and complaints about state organs and officials, including the right to sue government officials.

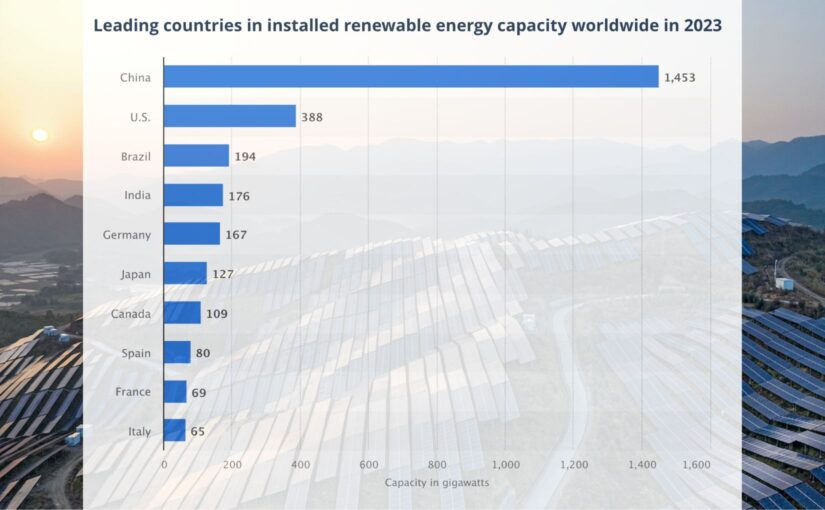

The NPC officially decides economic policy and has this year committed to the same targets as 2024: 5 per cent GDP growth; the creation of 12m jobs; incomes to keep pace with growth; a military spend of 7.2 per cent, that is, above the rate of growth but still below Nato’s soon-to-be-broken 2 per cent of GDP. Support will go to technology investment, green development, increased consumer spending, private and small businesses and a stock market clean-up.

“Too broad and vague,” say Western commentators, but the fact that China is sticking with last year’s targets, stabilising employment, trade and currency, speaks volumes as to the government’s confidence despite Trump’s turmoil.

China’s deliberative democracy still has a long way to go — gender representation for a start is poor, held back in part by differences in retirement age between men and women. Strengthening grassroots participation, representation, accountability and the implementation of the law — all are needed to advance the people-centred approach. The modernisation of socialist democracy in China is indeed still a work in progress.