This article by Casey Ho-yuk Wan, an attorney and independent researcher, analyzes the UN Human Rights Council’s 6 October 2022 vote against a Western-backed motion to hold a debate on China’s alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Casey observes that the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights is at serious risk of further losing credibility, particularly with the countries of the Global South, if it continues to allow itself to be used for a US-led anti-China propaganda campaign.

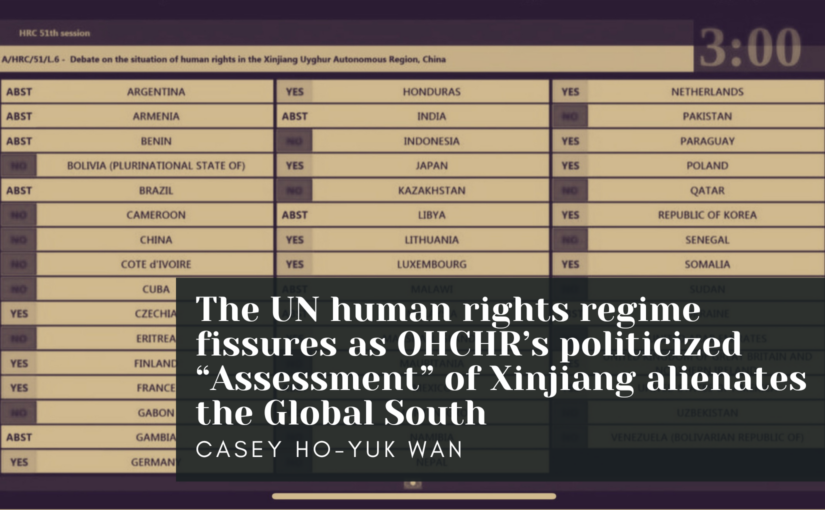

On 6 October 2022, the UN Human Rights Council (“HRC”) rejected the Western-sponsored draft decision A/HRC/51/L.6 (the “draft decision”) proposing that the HRC hold a debate on Xinjiang under agenda Item 2 at the 52nd HRC regular session in February 2023, with 17 supporting, 19 opposed, and 11 abstaining.[1] The draft decision’s defeat and the closure of 51st HRC regular session on 7 October 2022 provide an opportunity to reflect on the deepening fissures in the UN human rights regime, represented by the HRC and the Office of the High Commissioner of the Human Rights (“OHCHR”), and the growing alienation of the Global South, in particular with regards to Western politicization of human rights and the OHCHR’s complicity in the West’s instrumentalization of human rights as a weapon against developing countries.

Item 2 of HRC sessions generally cover “reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General” and thus customarily cover HRC-mandated proceedings. In the recently concluded 51st HRC regular session, Item 2 discussions included the report of the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, established by HRC resolution 39/2, the report of the OHCHR on promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka, authorized by HRC resolution 46/1, and the report of the High Commissioner on the situation of human rights in Nicaragua, authorized by HRC resolution 49/3.

It is on this basis that the West attempted to push the draft decision: “Taking note with interest of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, published on 31 August 2022, [the UN HRC] decides to hold a debate on the situation of human rights in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region at its fifty-second session under agenda item 2.” Even though the OHCHR’s “assessment” of Xinjiang enjoyed no UN HRC mandate which would customarily be required for inclusion as a topic of debate under Item 2, the West pushed ahead with the draft decision, hoping to “legitimize” the “assessment” through an HRC decision.

The OHCHR’s “assessment” of Xinjiang opened the door to the draft decision and the further politicization of the UN human rights regime. By framing the draft decision as due procedure and obscuring the fact that the OHCHR’s “assessment” of Xinjiang never enjoyed an HRC mandate, the West and its allies sought to institutionalize an image of China as a serious human rights violator, one who “may” have committed crimes against humanity, even when the Western campaign to castigate China on Xinjiang never enjoyed the approval of the international community of states. That the vote on the draft decision even happened marked the first time China’s human rights record has specifically been brought up for an HRC vote.[2] By all accounts, this move was a diplomatic escalation, with the blessing and complicity of an OHCHR which acted unilaterally and without a mandate or clearly-defined justification.

The OHCHR through its “assessment” changed the landscape of the HRC. Whereas previously, more states signed joint statements in the HRC supporting China’s position on Xinjiang than states signing joint statements in the HRC condemning China, the vote on the draft decision was of a fundamentally different character than the joint statements. To vote “no” on the draft decision and support China, it was no longer sufficient to uphold the values of non-interference in the context of Xinjiang, as joint statements in the past have done. Countries voting “no” on the draft decision must publicly express their displeasure either with the Western politicization of human rights in the HRC or with the conduct of the OHCHR or with both. In an increasingly delicate time of international turbulence, this was a much higher “ask” than simply reiterating China’s right to sovereignty and non-interference. It is perhaps safe to hazard a guess that the West and its allies were counting on the unwillingness of states to openly express their reservations vis-a-vis the OHCHR and the UN-backed global human rights apparatus behind it to push the draft decision and succeed in their goal of turning China into an international pariah.

The results speak for themselves. While the political implications of siding against the OHCHR seemed to have turned away some countries,[3] the additional pressure from the Western escalation also had the opposite effect of rallying previously silent countries to support China, resulting in only the second motion to be defeated in the HRC in its 16-year history since its founding in 2006.[4]

Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim-majority country, which has stayed silent on Xinjiang in the HRC context, voted no. So did Kazakhstan, the host of a prominent anti-China diaspora group, Atajurt, and the launching site of several Western NGOs and other actors in opposing China on Xinjiang, such as the Xinjiang Victims Database.[5] Senegal too, generally known as one of the more pro-West governments in Africa, voted no, a stance no less significant because Senegal this year holds the rotating presidency of the African Union. Perhaps most surprisingly, Qatar, who hosts the influential Al Jazeera media outlet, a regular critic of China on Xinjiang, also voted no.

Of 17 states voting for the draft decision, only 4 are of the Global South.[6] On the other hand, all opponents and abstainers (sans Ukraine) are of the Global South. Some of the opponents of the draft decision, as outlined above, would seemingly have strong interests in pressing this issue. This points to a latent anxiety on the part of the Global South, as well as to a deepening cleft between the West and its allies and the rest of the Global South in an increasingly bitter and escalating climate in the human rights space.

Global South disquiet with the OHCHR and its “assessment” of Xinjiang, as well as with the politicization of the HRC, was palpable throughout the 51st session. Discussions of Xinjiang at the 51st HRC session took place in an Item 2 “general debate on the oral update by the High Commissioner” on 13 September and in an Item 4 “general debate on the human rights situations that require the Council’s attention” on 26 September.[7]

On 13 September, China and 27 other countries (including Bolivia, Cameroon, Cuba, Eritrea, Nepal, UAE, and Venezuela, who all voted on the draft decision) expressly criticized the OHCHR’s Xinjiang “assessment.” Several states expressly called for respect of China’s sovereignty (for example, Lesotho, Mali). Others urged the OHCHR to follow established protocol and the principles of impartiality, objectivity and non-selectivity, in the spirit of constructive international dialogue and cooperation without double standards and politicization (such as Nigeria, the Philippines, Serbia, Vietnam).

The expressions of disquiet continued on 26 September in discussions about the Council’s attention and role in human rights work. Barbados held that “there is no room for double standards or the politicisation of human rights” before urging respect for the sovereignty of China. Malawi expressed worry of a “recurring perception [that the HRC] has become selective and polarised by politicization.” India argued that “the Council needs to function in a cooperative, non-confrontational, non-politicized and objective manner” and noted that “the deliberations in the Council under this Agenda Item have been unproductive and non-conducive to realization of the intended goals of promotion and protection of human rights.”

Perhaps most notably, Kenya, known as one of the more pro-West governments in Africa, and a state that has previously kept silence on the Xinjiang issue, issued an unusually strong statement on 26 September.

“Further, independence and territorial integrity of sovereign States and non-interference of their internal affairs represent the basic norms that govern international relations. In this regard, issues related to China’s internal affairs in Xinjiang should be left to China to address.

We are concerned that the Council may be used to pursue matters that have not been duly investigated or even authenticated. We, therefore, maintain that all states should promote and protect human rights through constructive dialogue and cooperation and firmly oppose politicization of human rights and double standards.”

Continued appeal for the HRC to embrace a constructive approach and reject politicization persisted on 6 October during the vote on the draft decision. While critical voices such as Bolivia accused the West of instrumentalizing the HRC for its own geopolitical ends and of using the cover of “procedure” and “debate” to open up a channel of continual attack on China, even moderate voices also expressed concern over the deepening politicization of the HRC.

In voting no on the draft decision, Indonesia reiterated that “[ensuring the safety and well-being of Muslims in Xinjiang] should be the sole focus of the Human Rights Council” and that the draft decision to hold a debate on Xinjiang would not make meaningful progress “especially because it does not enjoy the consent and support of the concerned countries.” Qatar similarly called for the HRC to “refrain from steps that could be described as politicization and could exasperate the situation” and reaffirmed the need to respect the principles of non-interference in internal affairs and the sovereignty of states, urging dialogue to settle differences in opinion. In abstaining, Mexico noted that it has consistently supported debate on the human rights situation in various regions of the world, so long as the debate is done constructively, and urged against politicization of the HRC’s work.

The picture of the HRC and the UN’s human rights regime, in light of all the foregoing, is grim. Far from being a system dedicated to the technical and non-political promotion of human rights, the UN human rights regime is more split, politicized, and polarized than ever before. An air of distrust and antagonism dominates discussions in the HRC. The fact that all country-specific resolutions of the HRC are aimed at developing countries[8] only highlights the roots of Global South frustration with the UN’s human rights regime, made visible through the Global South’s reaction to the politically-motivated draft decision.

The OHCHR shares no small part of the responsibility for this sorry state of affairs. While the OHCHR is purposed to be a professional and technical body dedicated to the impartial promotion of human rights, the OHCHR has seemingly already sided with the West and its allies over China through its “assessment”. The OHCHR also enabled the draft decision through its “assessment”, thereby perpetuating the historic HRC bias against the Global South. This cannot but instill a sense of worry and foreboding among the Global South.

The OHCHR’s “assessment” enabling the draft decision was startling biased, disregarded input from China’s government, civil society, and people, did not enjoy the mandate of the UN HRC, and violated the principles and guidelines of the general mandate of the OHCHR as outlined in Resolution 48/141, under which the OHCHR claimed it was authorized to pursue the “assessment.”[9] The conduct of the OHCHR in selectively ignoring the high-profile human rights violations of Western countries, including alleged crimes against humanity such as war crimes, while seemingly embarking on an unsanctioned crusade against a major developing country, is nothing more than double standards at best and a willingness to abet Western countries in instrumentalizing and politicizing human rights as a tool against developing countries at worst. From the perspective of the Global South, the OHCHR has become little more than an instrument for the West to impose its will on developing countries, seemingly beholden only to the interest of Western countries, the citizens of whom constitute 80% of the OHCHR’s staff.

The context of increasing hostility in the HRC and the appeals of Global South countries urging the OHCHR to return to protocol, the principles of impartiality, objectivity, and non-selectivity points towards an OHCHR that has alienated the Global South through its action, not least through its unsanctioned and flawed “assessment” of the situation in Xinjiang. That a Western-initiated motion, given powerful political impetus by the OHCHR’s work and “assessment”, would fail along partisan lines dividing the West from the rest is, in itself, a highly concerning indication of the OHCHR’s loss of credibility and currency with the governments and people of the Global South.

The alienation of the Global South in human rights spaces, which threatens the efficacy of the UN human rights regime, is set to only increase over time, unless the OHCHR can rectify its behavior and return to its mandate of impartiality, objectivity, and non-selectivity, or Western countries cease politicizing human rights and work instead to create a constructive and technical environment for the promotion of human rights.

Footnotes

[1] The draft decision was sponsored by Albania, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Marshall Islands, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Slovakia, Sweden, Türkiye, the United Kingdom, and the United States. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/G22/505/63/PDF/G2250563.pdf?OpenElement.

To pass, the decision must have had more supporting than opposed, as absentations are not counted.

Voting in favor were: Czechia, Finland, France, Germany, Honduras, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Marshall Islands, Montenegro, Netherlands, Paraguay, Poland, the Republic of Korea, Somalia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Voting against were: Bolivia, Cameroon, China, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Eritrea, Gabon, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Mauritania, Namibia, Nepal, Pakistan, Qatar, Senegal, Sudan, UAE, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela.

Abstaining were: Argentina, Armenia, Benin, Brazil, Gambia, India, Libya, Malawi, Malaysia, Mexico, Ukraine.

The UN HRC is made up of 48 states who are elected on staggered terms. Russia is currently suspended from the HRC due to a 7 April 2022 UN General Assembly resolution, leaving 47 members. The UN HRC mandates 13 members from “African States”, 13 members from “Asia-Pacific States”, 6 members from “Eastern European States”, 8 members from “Latin American and Caribbean States”, and 7 members from “Western Europe and Other States” (which includes, among other countries, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Türkiye, and Israel).

The geographic spread of the votes are: African States 1-8-4, Asia-Pacific States 3-7-3, Eastern European States 4-0-2, Latin American and Caribbean States 2-3-3, Western Europe and Other States 7-0-0. https://hrcmeetings.ohchr.org/HRCSessions/RegularSessions/51/DL_Resolutions/A_HRC_51_L.6/Voting%20Results.pdf.

[2] Han Chen, UN Human Rights Council rejects debate on Xinjiang abuses, Axios, https://www.axios.com/2022/10/06/un-human-rights-reject-debate-china-xinjiang-abuses.

[3] Benin, Gambia, and Libya previously signed joint statements in support of China on Xinjiang but abstained in the draft decision vote, while Somalia, also a signatory of previous supportive joint statements, voted for the draft decision.

[4] The first time a motion was defeated in the HRC was last year 7 October 2021, A/HRC/48/L.11, which sought to extend the mandate of the Group of Eminent International and Regional Experts in Yemen for another two years. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/G21/267/64/PDF/G2126764.pdf?OpenElement; https://hrcmeetings.ohchr.org/HRCSessions/RegularSessions/48session/DL_Resolutions/A_HRC_48_L.11/Result%20of%20the%20vote.pdf.

The defeat was seen in Western media circles as a defeat of a Western initiative by a Saudi-led effort. Stephanie Nebehay, U.N. ends Yemen war crimes probe in defeat for Western States, Reuters, October 8, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-ends-yemen-war-crimes-probe-historic-defeat-rights-body-2021-10-07/.

[5] Atajurt is an activist organization in Kazakhstan centered around Chinese diaspora of Kazak nationality in Kazakhstan and has been a significant actor in the Xinjiang controversy. As such, Kazakhstan likely has domestic considerations in how it approaches China, making its decision to vote no on the draft decision surprising. That said, Kazakhstani authorities appear to have a difficult relationship with Atajurt.

Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, a foreign volunteer with Atajurt, estimates that “almost 70-80 percent of the information about the concentration camps in Xinjiang came from Atajurt, especially in the early days of the struggle [2017-18].”

Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, Documenting the Tragedy in Xinjiang: An Insider’s View of Atajurt, The Diplomat, January 16, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/documenting-the-tragedy-in-xinjiang-an-insiders-view-of-atajurt/

Gene Bunin, manager of the website “Xinjiang Victims Database” and at one point based in Almaty, Kazakhstan, has stated that “There probably would not be a [Xinjiang Victims Database] without Atajurt, because a lot of the useful data that’s in there comes from their work.”

Gene A. Bunin: On Xinjiang, Atajurt, and Serikjan, The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, March 18, 2019, https://livingotherwise.com/2019/03/18/gene-bunin-xinjiang-atajurt-serikjan/.

[6] Honduras, the Marshall Islands, Paraguay, and Somalia. Somalia is especially surprising, as it had supported China in joint statements at the HRC before, only to vote for the draft decision here.

[7] Oral statements of states in HRC sessions can be reviewed on the HRC Extranet: https://hrcmeetings.ohchr.org/Pages/default.aspx.

[8] Statement of H.E.Ambassador CHEN Xu at the 51st Session of the Human Rights Council Opposing Xinjiang-related Draft Decision(A/HRC/51/L.6) Tabled by the U.S. and Some Other Countries, http://geneva.china-mission.gov.cn/eng/dbtxwx/202210/t20221007_10777584.htm.

[9] Alfred de Zayas, The Flaws in the “Assessment” Report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on China, Counterpunch, September 6, 2022, https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/09/06/the-flaws-in-the-assessment-report-of-the-office-of-the-high-commissioner-for-human-rights-on-china/.

I am from Vancouver,Canada and i wanted to say that the OHCHR will be a problem while it allows the US Gov’t to tell it what to do. The problem with the UN overall is that the US Gov’t got to much influence in the decisions that are made by the different bodies of the UN like the OHCHR. That has to change before these bodies of the UN can make correct decisions.

This is a very interesting analysis.