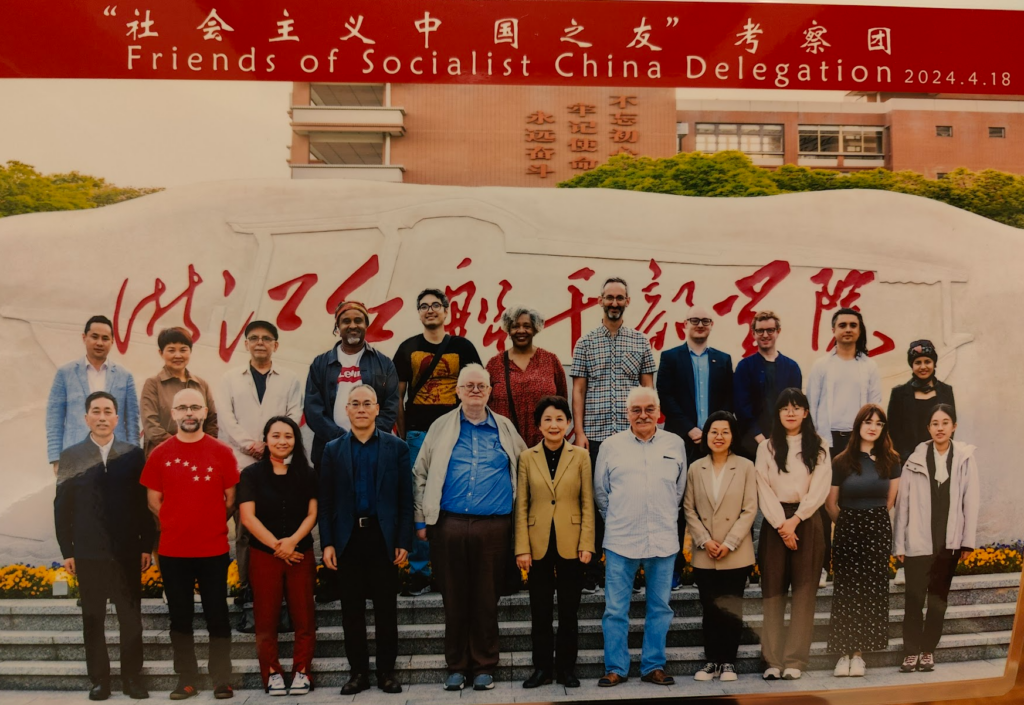

The first exclusive Friends of Socialist China delegation to the People’s Republic of China took place from 14 to 24 April 2024.

Invited by the China NGO Network for International Exchanges (CNIE), which works under the direction of the International Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (IDCPC), 14 comrades (11 from Britain, two from the United States and one from Ireland) visited Beijing, Hangzhou and Jiaxing (Zhejiang province), and Changchun and Siping (Jilin province). The packed program featured visits to public service and community facilities, historic revolutionary sites and museums, political, scientific, cultural, industrial, and agricultural organisations, exhibition centres and cooperatives, and famous scenic spots among others.

Serving the people

Our first site visit, on 15 April, was to the Beijing headquarters of the ‘12345’ government service hotline, where 1,500 employees (mostly CPC members) work in shifts to provide a single point of access for any and all problems and queries – for example, rubbish being left on the street, heating not working, or older people not receiving food deliveries. The service aims to provide “a bridge connecting people, party and government”, and is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, free of charge. We were told that the Beijing HQ typically receives 60,000 calls a day, and 90 percent of these are resolved to the user’s satisfaction. The service in some form has been operating for 30 years, with substantial improvements over that period, including most recently support for more languages allowing visiting tourists and international residents to utilise the hotline.

Thanking our hosts at the 12345 hotline HQ, head of delegation Keith Bennett observed that the service embodies three important characteristics of the Chinese Revolution. Firstly, it represents a modern implementation of the slogan ‘serve the people’. Secondly, it is consistent with the mass line: “take the ideas of the masses (scattered and unsystematic ideas) and concentrate them (through study turn them into concentrated and systematic ideas), then go to the masses and propagate and explain these ideas until the masses embrace them as their own, hold fast to them and translate them into action, and test the correctness of these ideas in such action”. Lastly, the 12345 service is an example of using modern technology in order to carry out social investigation, “investigating the conditions of each social class in real life”. The use of big data allows the local government to notice trends in residents’ enquiries and proactively solve problems and improve services.

The spirit of serving the people was also evident at the Party-masses Service Centre of Jiaxing, Zhejiang, which we visited on 19 April. Opened in 2021, it’s a hub for training, exhibitions, volunteer services, social organisation incubation, and provision of mental health services. Delegates were amazed to learn that people can register for counselling and get an appointment booked for the next day – free of charge. Also impressive were the meeting spaces and lecture halls that could be hired free of charge for use by the local community. The therapy is framed within a context of public health, and is based on the principle that “only with peace of mind can the people and the country be safe.”

The birth of Marxism in China

One of the central aims of the delegation was understanding the early development of Marxism in China. Towards that end, we visited the Red Building of Peking University and the Red Boat in Jiaxing, Zhejiang.

The Red Building was the main campus of Peking University from 1918 to 1952, and was a key hub for the New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Movement, which were pivotal events in the early stages of the revolution and the spread of Marxism within the country. Peking University was the first college in China to introduce Marxism to its students, thanks primarily to the efforts of Li Dazhao, co-founder of the CPC. The building was renovated and reopened as a museum in 2021, and features 1,357 artefacts along with six reconstructed rooms made to appear as they did in the 1920s, when Li Dazhao, Mao Zedong, and other pioneers of Chinese Marxism worked there.

The museum’s curator explained how the progressive New Culture Movement that emerged in the mid-1910s formed the intellectual breeding ground for the May 4th Movement – an anti-imperialist student movement which arose to protest the Chinese government’s shameful acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles (which allowed Japan to hold on to the territories in Shandong which had been surrendered by Germany in 1914). The May 4th movement in turn was the immediate precursor of the CPC and the anti-imperialist united front.[1] As Mao Zedong wrote, the May 4th Movement “marked a new stage in China’s bourgeois-democratic revolution against imperialism and feudalism… With the growth and development of new social forces in that period, a powerful camp made its appearance in the bourgeois-democratic revolution, a camp consisting of the working class, the student masses and the new national bourgeoisie.”

In the discussion at the Red Building, the significance of the October Revolution was also mentioned. The May 4th Movement arose in 1919, just a year and a half after the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, charting a course for the peoples of the world to overcome capitalism and break with imperialism. One of the first acts of the revolutionary government in Russia was to tear up the unequal treaties that had been imposed on China by the tsarist regime. Thus the October Revolution had a profound impact on the development of the revolutionary and anti-imperialist movement in China. In Mao’s words: “The salvoes of the October Revolution brought us Marxism-Leninism. The October Revolution helped progressives in China, as throughout the world, to adopt the proletarian world outlook as the instrument for studying a nation’s destiny and considering anew their own problems.”

While the Chinese revolutionary movement was very much inspired by the example of October, there were also important differences between the Chinese and Russian revolutions. At Renmin University’s School of Marxism Studies, where we exchanged views with Wu Fulai (vice-chair of Renmin University council) and several other prominent academics, it was noted that the successes of the CPC over the course of a century are due in large measure to its adaptation and development of Marxism in the light of China’s conditions. In the 1920s and 1930s, the industrial working class only constituted a tiny fraction of the Chinese population, and capitalism was only in the early stages of its development. Mao’s profound insight was that it was possible to unite the vast majority of the (largely peasant) population around a working class ideology in a revolution against imperialism and feudalism. Hence the first Chinese Soviet, in the border region between Jiangxi and Hunan, drew important lessons from the Bolsheviks but was nonetheless markedly different to the Petrograd Soviet.

Our delegation spent three days in Jiaxing, Zhejiang, which is the site of the Red Boat, where the first National Congress of the CPC concluded in 1921 and where the founding of the party was proclaimed. The Red Boat symbolises “the starting point of the Party’s century-long journey and also the beginning of great changes for China and its people.”

At the Zhejiang Red Boat Executive Leadership Academy, Professor Peng Shijie, director of the Department of CPC History, gave a detailed and fascinating talk on the early dissemination of Marxism in China, painting a vivid picture of the Chinese people’s attempts in the late 19th and early 20th century to put an end to the Century of Humiliation – the tragic period of Chinese history beginning with the First Opium War in 1839.

Professor Peng noted that several attempts had been made to solve China’s problems with Western ideas – including in the Westernisation Movement and the Reform Movement of the late Qing Dynasty, and the New Culture Movement in the 1910s. He described three major events that contributed to China’s progressive youth settling on Marxism as their primary ideological weapon: World War 1, the October Revolution, and the May 4th Movement.

The immense devastation caused by World War 1 caused many Chinese intellectuals to lose their confidence in Western capitalism. Then the October Revolution changed the world forever, showing that the oppressed peoples could rise up and take control of their own destiny. Then the May 4th movement coalesced popular opinion around anti-imperialist action, and confirmed the belief that the task of liberating China could only be carried out by the Chinese people. Marxism, combined with Chinese traditions and applied to China’s circumstances, provided the theoretical framework for devising a strategy to defeat imperialism, dismantle feudalism and achieve national rejuvenation.

Professor Peng pointed out that while China’s creative adaptation and application of Marxism started with Mao Zedong Thought, it remains a constant feature of the Chinese revolutionary process. Reform and Opening Up is also an important example of China’s creative adaptation of Marxism, as is Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era.

Chinese modernisation

At the Zhejiang Provincial Committee Party School in Hangzhou, we had a detailed discussion about China’s socialist modernisation, led by Chen Lixu, the school’s former vice-president. Professor Chen pointed out that, since World War 2, the only developing countries that have successfully modernised are South Korea and Singapore – both with significant assistance from the US, which nurtured these capitalist economies as part of its long-term campaign against communism. Even today, there are no ‘developed’ countries in Africa or Latin America. This shows how difficult the process of modernisation is, and how the West’s prescriptions for modernisation—‘liberal democracy’ and free markets—don’t work. Developing countries need to find their own path to modernisation.

China’s modernisation is a particularly difficult and complex case, due to its enormous population, and the fact that in 1949 at the time of China’s revolution its level of development was among the lowest in the world. Professor Chen observed that, of the 37 countries that have achieved modernisation, 22 of them have a population of under 10 million. Furthermore, as a socialist country, China has a responsibility to build a modernisation characterised by common prosperity, that adheres to the principles of ecological sustainability, and that will “neither tread the old path of colonisation and plunder, nor the crooked path taken by some countries to seek hegemony once they grow strong.”

On the other hand, China does have certain advantages. The leadership of the CPC ensures that the interests of the masses are kept in mind at all times, and allows the country to pool resources for major projects. Furthermore, the Chinese Revolution succeeded in “toppling the three mountains” of imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism, and the early decades of socialist construction wiped out illiteracy, spread education and healthcare throughout the country, and almost doubled life expectancy. This provides the basic foundations upon which China’s modernisation project is being built. Such foundations have allowed for the people of China to achieve the first of their Two Centenary Goals (with the building of “a moderately prosperous society in all respects” being achieved in 2021), and to be in a strong position to complete the second goal of “building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects” by 2049.

Green revitalisation

Our delegation visited Jilin in Northeast China. With a population of 23 million, Jilin borders both Russia and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and—along with the other Northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang and Liaoning—was China’s earliest industrial base and an important area for grain cultivation.

Much like former industrial heartlands elsewhere in the world, Jilin has struggled to adapt to a changing economy characterised by rising levels of automation and digitalisation. However, unlike Britain’s largely-fictional program of “levelling up”, or the US’s empty talk of reviving the Rust Belt, the revitalisation of China’s Northeast is proceeding apace.

A highly important feature of Jilin’s revitalisation program is its integration with China’s ecological objectives. For example, the Jilin-based state-owned CRRC Changchun Railway Vehicles is the world’s leading manufacturer of high-speed rail (HSR), and has played a crucial role in the extraordinary expansion of HSR in China over the last two decades (China currently accounts for two-thirds of the world’s network). Earlier this year, China’s first hydrogen-powered urban train, was successfully tested in Jilin’s provincial capital, Changchun, “achieving a full-system, full-scenario and multi-level performance verification”.

Another area of revitalisation and development was the strengthening of co-operative organisations, particularly in the agricultural sector, one of which we visited. By combining ownership of farming equipment, pooling their buying power, and coordinating marketing and negotiation strategies, the local agricultural workers were able to continually improve their harvests, enhance their income, and build a more resilient industry in the area.

Clean energy makes up 60 percent of Jilin’s power mix, the result of vast investment in solar and wind power, along with key innovations in the new energy industrial chain. Jilin’s forest coverage stands at 45 percent, and its 36 nature reserves take up 17 percent of land area. One of our site visits was to a demonstration zone for green food production in Lishu County, where we learned about the elaborate efforts to protect the region’s carbon-rich and highly fertile black soils, which are under significant threat arising from climate change and biodiversity loss. Xi Jinping described China’s black soil as being “as treasured as giant pandas”. The methods of soil protection developed in Lishu are being promoted and implemented throughout Northeast China.

It’s extremely inspiring to see how seriously ecological issues are treated in China, and the degree to which they are built into economic planning and policy-making. We learnt about the appointment of river, lake, forest, and field chiefs, who champion the protection of their respective natural environments, with powers of veto over development projects that could cause damage. China’s modernisation really is the modernisation of harmony between humanity and nature. The West certainly has something to learn from China on this score.

Study of Marxism

Our delegation visited schools of Marxism at both Renmin University (Beijing) and Jilin University, as well as CPC training schools in Jiaxing, Hangzhou, and Changchun. One thing that’s abundantly clear is that in China the study and development of Marxism is taken extremely seriously, and there are hundreds of departments doing serious and innovative work in this field. Furthermore, their work is integrated with practice in the construction of socialism and the pursuit of a global community of shared future.

Coming from Britain, the US, and Ireland, it was refreshing and inspiring for our delegates to see the prominence given to Marxist ideas in the academic world, particularly given the increasingly hostile environment that exists for progressive and anti-imperialist academics in the West. It’s an oft-repeated trope that the West, unlike China, enjoys academic freedom. In reality, China allows a far broader range of opinion within academia than the West, but its default ideology is that of the working class. Meanwhile in the West there is escalating repression of progressive ideas, and the default ideology is that of the capitalist class.

Building friendship, developing people-to-people links, and opposing the New Cold War

In Beijing we had fascinating exchanges with Yuan Zhibing, Secretary General of the Chinese Association for International Understanding (CAFIU) and Ai Ping, Vice President of CAFIU. We discussed the importance of developing people-to-people links between China and the West; the continuing evolution of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics; the global relevance of China’s anti-poverty campaign; the escalating US-led New Cold War being waged against China; the growing social and economic problems in the West; and more. Yuan Zhibing expressed his strong support for Friends of Socialist China’s first delegation, saying that when comrades from abroad visit China, “it shows us Chinese that we are not alone on the path to socialism.”

In Beijing we also had an inspiring meeting with comrades from Contemporary World Press (CWP), the publishing house of the International Department of the CPC. Chief Editor Li Shuangwu described CWP’s efforts to strengthen exchanges and cooperation with other parts of the world and to spread understanding abroad of China’s policies and successes. We discussed the importance of countering the relentless anti-China New Cold Propaganda emanating from the West, and the value of telling China’s stories well, particularly in relation to its world-historic achievements in poverty alleviation and green energy, its contributions to Marxist theory, and its role in international affairs – pursuing a multipolar future and a global community of shared future for humanity.

At the headquarters of the Center for China and Globalization think tank in Beijing, we had a thought-provoking and wide-ranging discussion on the importance of global cooperation, particularly in relation to artificial intelligence (AI) governance. AI has enormous potential to improve human wellbeing, but it is also associated with major—even existential—threats. As with climate change, pandemics, antimicrobial resistance and the threat of nuclear war, it’s only possible to manage the risks of AI through deep and thorough-going global cooperation. Unfortunately the West, led by the US, is more focused on containment of China than on cooperation with China. For this reason, it’s crucial to build people-to-people links between China and the West, to develop people’s understanding of China, to show the masses of people in the imperialist heartlands that China is not their enemy, and to create a powerful movement against the New Cold War.

All members of the delegation learned an enormous amount about China’s ongoing socialist revolution, and were hugely inspired by China’s progress and its commitment to peace, to sustainability, to common prosperity, and to global development. The famous phrase from Confucius “it is such a delight to have friends coming from afar” was a theme amongst those academics, workers, party members, and others with whom we met on our delegation, and we were extremely grateful for their friendliness, generous hospitality, and, most importantly, their willingness to answer our many questions about China’s socialist path, from the highly theoretical to the realities of day-to-day life. In 1989, Deng Xiaoping commented to former Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere that, “so long as socialism does not collapse in China, it will always hold its ground in the world.” Those words certainly resonate for socialists visiting China today.

[1] At time of writing it is the 105th anniversary of the May 4th movement, and contemporary parallels with the global anti-imperialist student movement opposing the genocide in Gaza have been commented upon both inside and out of China.

15 thoughts on “Delegates from Britain, Ireland and the US learn about the past, present and future of Socialist China”