November 21 is the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Jamaica. Coming 10 years after the Jamaican people won independence from British colonial rule, the country became the second in the English-speaking Caribbean, and the first of the islands, to establish relations with the People’s Republic after Guyana had led the way some five months previously.

Jamaica’s move came eight months after the People’s National Party (PNP) assumed office, with Michael Manley becoming Prime Minister. Manley sought to take his country in the direction of socialist orientation, not only recognising the People’s Republic of China, but especially forging close ties with socialist Cuba and giving strong support to the liberation movements in southern Africa. He established a minimum wage for all workers, including domestic workers, introduced free education and adult literacy programs, promoted land reform, lowered the voting age, and introduced equal pay for women, alongside a host of other progressive measures. At the 1979 Non-Aligned Summit in the Cuban capital Havana, he declared: “All anti-imperialists know that the balance of forces in the world shifted irrevocably in 1917 when there was a movement and a man in the October Revolution, and Lenin was the man.”

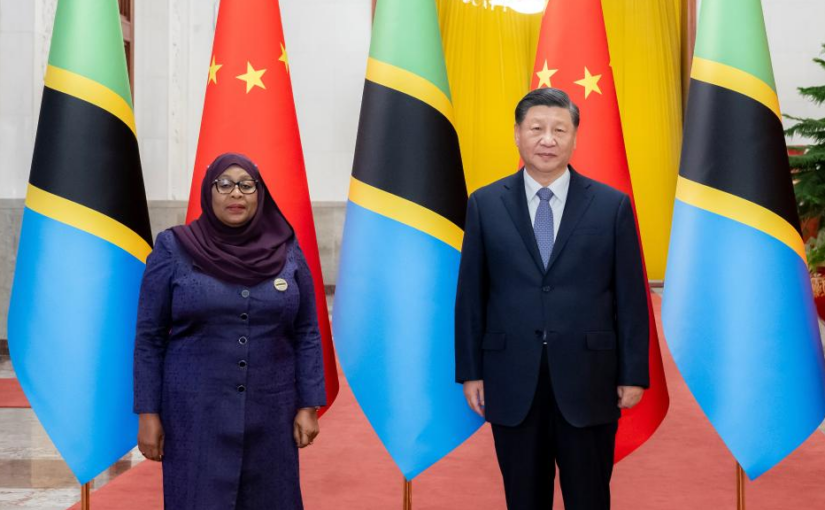

President Xi Jinping greeted the 50th anniversary with an exchange of messages with Jamaican Governor-General Patrick Allen, in which the Chinese leader noted that the two countries’ relations had “always maintained a good momentum of development, with the two sides deepening political mutual trust, achieving fruitful results in practical cooperation and increasing friendship between their people.”

Premier Li Keqiang also exchanged messages with Prime Minister Andrew Holness.

Writing for CGTN, Jamaica’s Ambassador to China, Antonia Hugh said that the two countries had fostered “a strong, dynamic and vibrant partnership.” Although the diplomatic relationship dates back 50 years, people-to-people friendship begins from 1849, when the first group of Chinese arrived on the island.

Ambassador Hugh hailed the countries’ bilateral partnership, highlighting in particular the fields of infrastructure development, health and education.

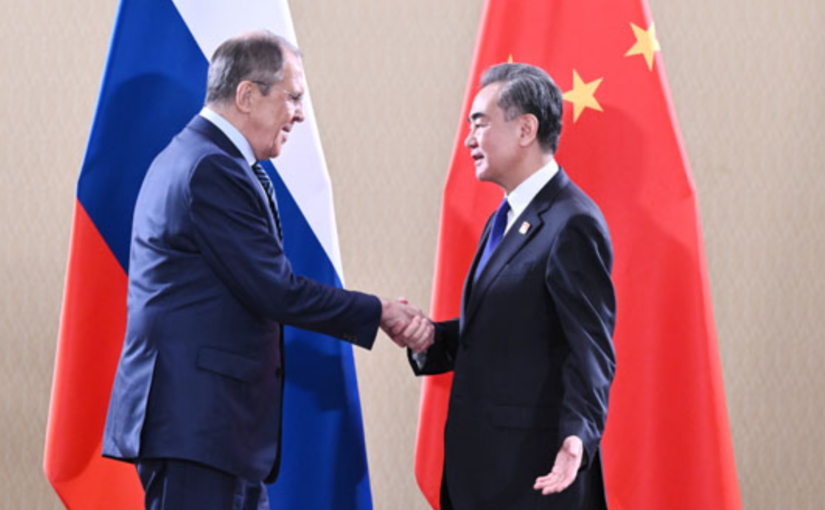

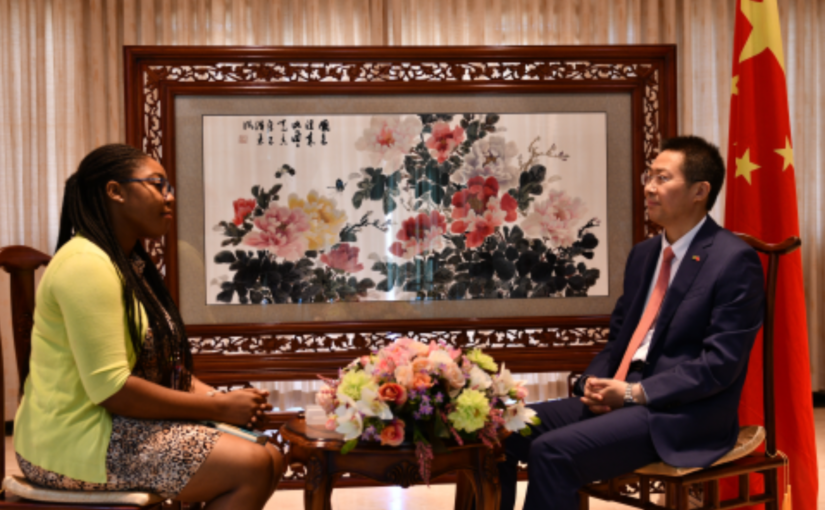

China’s Ambassador to Jamaica, Chen Daojiang took up his post earlier this year. In his first interview, given to Jamaica Information Services (JIS) on July 29, Ambassador Chen hailed the 60th anniversary of Jamaican independence and continued:

“Slavery and colonialism have brought catastrophic sufferings to the world and left a very disgraceful page in human history. The days when Western colonists could do whatever they want have gone. However, we must also realize that the colonialist thinking and its derivative power politics and bullying are still manifested in various forms in international relations, which are still severely impacting the normal international order and seriously undermining the sovereignty, security, and development interests as well as political, economic and social stability of relevant countries. The international community still has a long way to go to completely eliminate the impacts of slavery and colonialism.

“There is a proverb in Jamaica, which goes ‘Wi likkle, but wi tallawah’. China also always upholds that all countries are equal, regardless of their size. The history of Jamaica’s fight against the colonial rule and slavery was laudable and emotionally moving. The braveness, resilience and wisdom shown by Jamaican people in the fight is very impressive and admirable. China had similar history with Jamaica in modern times when both countries were invaded and suppressed by Western colonialists for a long time and both countries faced same tasks of seeking independence of the nation, prosperity of the country and happiness of the people. Similar history makes our two countries easier to understand and support each other.

“In 1949, under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the People’s Republic of China was established. China has completely expelled the forces of Western imperialists in China, and the Chinese people has truly become the master of the country since then. Under the strong leadership of the CPC, China has successfully embarked on a development path that suits its national conditions, namely the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and has achieved the tremendous transformation from standing up and growing prosperous to becoming strong. China is now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects.”

The following articles were originally published by the Xinhua News Agency and CGTN and on the website of the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

Xi exchanges congratulations with governor-general of Jamaica over 50th anniversary of diplomatic ties

Chinese President Xi Jinping on Monday exchanged congratulatory messages with Governor-General of Jamaica Patrick Allen on the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Jamaica was among the first countries in the English-speaking Caribbean region to establish diplomatic relations with China, Xi said.

In the past 50 years, China-Jamaica ties have always maintained a good momentum of development, with the two sides deepening political mutual trust, achieving fruitful results in practical cooperation and increasing friendship between their people, he added.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, Xi said, China and Jamaica have been helping each other and jointly fighting the coronavirus, injecting fresh impetus into the friendly cooperation between the two countries.

Xi said he attaches great importance to the development of China-Jamaica relations, and is ready to work with Allen, taking the 50th anniversary as a new starting point, to deepen cooperation in various fields, promote high-quality Belt and Road cooperation, jointly lead China-Jamaica strategic partnership to a new level, and work together to build a China-Jamaica community of a shared future in the new era.

Allen said since the establishment of their diplomatic ties, friendly relations between Jamaica and China have been developing continuously with cooperation in various fields yielding remarkable results, which is encouraging.

He added that Jamaica is ready to continue to strengthen cooperation with China and further deepen their strategic partnership.

Also on Monday, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang exchanged congratulatory messages with Jamaica’s Prime Minister Andrew Holness.

Li said Jamaica is an important cooperative partner of China in the Caribbean region, adding that China is ready to work with Jamaica to further deepen and cement the strategic partnership, so as to bring more benefits to their people.

For his part, Holness said Jamaica highly appreciates China’s valuable support for its economic growth and social development and his country stands ready to continue to strengthen cooperation with China to ensure that the strategic partnership will benefit their people.

Jamaica and China’s golden 50: Special bonds of friendship

As the Ambassador of Jamaica to the People’s Republic of China, I welcome this opportunity to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Jamaica and the People’s Republic of China, and to celebrate the special bonds of friendship, which our two countries have enjoyed over these 50 years.

On November 21, 1972, Jamaica proudly created diplomatic history when it became the first English-speaking Caribbean island to support the one-China principle, and establish diplomatic relations with China. Since then, Jamaica and China have made remarkable progress in fostering a strong, dynamic, and vibrant partnership.

Jamaica and China have longstanding people-to-people engagement, which goes beyond 50 years, dating as far back as 1849, when the first cohort of Chinese arrived in the island, followed by a larger cohort in 1854. The 1972 landmark Agreement was, therefore, a consolidation of the special relationship that had long existed between our peoples.

In this regard, we celebrate the fact that today, Chinese Jamaicans have been wonderfully woven into the fabric of Jamaican society and have become an inseparable part of our vibrant cultural heritage. Chinese in Jamaica and Jamaicans of Chinese descent have contributed greatly to Jamaica’s economy, particularly in the areas of retail, banking and the culinary arts, as well as in the political and musical spheres.

The special relationship between Jamaica and China is underpinned by deep mutual respect and shared values, and is continuously reinforced by our extensive cooperation at the bilateral, regional and multilateral levels.

In this connection, both countries have consistently demonstrated an unwavering commitment to the development of a sustained technical and functional cooperation program, which has allowed us to forge and maintain our dynamic and mutually beneficial partnership.

Within a global context, the People’s Republic of China has made an indelible mark on almost every sphere of human endeavor, including in the arts, medicine, education, economics, engineering, science and technology, just to name a few – and as a result, the world is looking to China as a key driver of global economic development, and a partner in addressing common challenges.

China is also home to the world’s largest population. This ancient civilization with a legacy of innovation and focused determination, has become the world’s largest manufacturing economy and the largest exporter of goods, achieving strong, sustained economic growth and inclusive development for its people.

We wish to commend China on its accomplishment of eradicating extreme poverty. We are impressed by the fact that China has met the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development target 10 years ahead of schedule and thus has contributed to greatly to global poverty reduction.

We admire China’s steadfast commitment to the goal of modernization and its relentless pursuit of situating the needs of the people within that mandate and we look forward with anticipation, to the unfolding of its modernization plan from 2020 through to 2035 and beyond.

In light of the foregoing, I would also like to commend China for pursuing, with the same tenacity it pursues national development, international outreach and in particular, South-South Cooperation, through which Jamaica has benefited tremendously.

Through our bilateral cooperation agreements and initiatives, the government of China has provided invaluable support to Jamaica particularly in the areas of infrastructure development, health, and education.

Today, China stands as one of the key partners in Jamaica’s drive for infrastructural development and modernization. Across Jamaica, there are many examples of this fruitful partnership, including the new fit-for-purpose headquarters of the Foreign Ministry and the outstanding Edward Seaga Highway, which connects the north and south of the country.

Jamaicans are appreciative of China’s instrumental role in the achievement of our social development goals. Given the critical role that education plays in development, China has sought to make meaningful contributions to Jamaica’s education landscape.

Through China’s medical scholarship program, the dreams of many ambitious Jamaican students who aspire to pursue medicine are financed and supported. Hundreds of other students have been awarded scholarships to pursue studies in China at top universities and all have expressed their gratitude at the opportunity to use what they have learned in China to build their country.

Within this vein, I am reminded that many Jamaican teachers have been assigned to work across China’s provinces, thereby improving their individual economic realities in practical and fulfilling way.

It is often said that “hard times reveal good friends” and so I would like to seize this opportunity to express my profound gratitude to the Chinese government and people for their support and assistance throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, arguably among the most difficult years of our lives. Throughout this pandemic we observed how the Chinese spirit of solidarity, resilience and innovation has led a nation to rebound from the pandemic with renewed agility.

We observed how China, in the midst of its own trials and challenges, chooses continuously, to cling to hope and extend its goodwill by helping other countries including my own. In this connection, I reiterate our gratitude for China’s commitment in the construction of the Western Children’s and Adolescents’ Hospital in Montego Bay, another first in the English-speaking Caribbean.

China and Jamaica elevated relations to that of a strategic partnership in 2019 during the visit of Prime Minister Andrew Holness to China. This was a watershed moment in our history, which followed the groundwork laid in previous official visits and high-level exchanges, including when we opened the Jamaican Embassy in China’s capital Beijing in 2005; and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Jamaica in 2009, when he was Vice President.

As we celebrate our 50th anniversary, Jamaica intends to increase the frequency and scope of our policy dialogue with China. We look forward to developing innovative and lasting platforms for direct interaction between policymakers, business, and other vital segments of society. We also look forward to finalizing more groundbreaking agreements and MOUs, which will serve to build mutual understanding to create more opportunities for commerce and social programs to thrive.

On a cultural note, cognizant of the fact that Jamaican products provide Chinese people with enriched and diversified access to new cultural experiences, we will continue producing and exporting consistent volumes of the luxurious Jamaican Blue Mountain Coffee to China. We will also seek to provide more delicious lobsters and aged rum and continue to share the magic of Reggae music with the beautiful people of China. Similarly, we encourage landmark institutions such as the Confucius Institute, established at the University of the West Indies in Kingston, to enhance the dissemination of Chinese history and culture among Jamaicans.

On this, our Golden Jubilee – our Golden 50, let us seize this historic opportunity to promote our “win-win” relationship under the guidance of our leaders and endeavor to continue making solid contributions to building a community with a shared future for humanity.

Happy 50th anniversary Jamaica and China!

Happy Golden Jubilee!

Chinese Ambassador to Jamaica Chen Daojiang Gives an Interview to Jamaica Information Services

On July 29, 2022, H.E. Mr. Chen Daojiang, Ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to Jamaica gave an interview to Jamaica Information Services (JIS), expressing congratulations on the 60th anniversary of the independence of Jamaica and answered questions regarding the China-Jamaica relations, the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Jamaica and the Global Development Initiative, etc. The interview has recently been published and broadcast on the website and radio of JIS and RJR (Radio Jamaica). The full interview is as follows:

Ambassador Chen Daojiang: I am very glad to be interviewed by Jamaica Information Services on the occasion of upcoming 60th anniversary of the Independence of Jamaica, and this is my first interview during my tenure. First of all, on behalf of the Chinese Government and Chinese people, I would like to extend warm congratulations and best wishes to the Jamaican Government and Jamaican people. Big up, Jamaica!

I am honoured to come to Jamaica, a shining pearl on the Caribbean Sea, to serve as the Chinese Ambassador to Jamaica. Over the past two months, I have paid courtesy calls on many Jamaican officials and friends from various walks of life, talked with heads of Chinese enterprises and communities in Jamaica, toured several projects contracted by Chinese enterprises, and visited the National Gallery of Jamaica, from which I got some strong feelings that Jamaica is a beautiful, open and vibrant country and Jamaicans are enthusiastic, friendly and optimistic. The friendship between the two governments and two peoples is profound. Jamaica enjoys geographic advantages, unique culture and abundant creativity, and has huge potential and a promising future for economic and social development. I believe that Jamaica will yield more and more development achievements in the future.

JIS: What’s your general remarks on the importance of the island’s Diamond Jubilee? Do the people of China think it’s also important and why?

Ambassador Chen: On 6 August 1962, Jamaica declared its independence from colonial rule, opening a new chapter in Jamaican history. Jamaica entered a stage of rapid economic growth under the leadership of The Right Excellent Sir William Alexander Bustamante, the first Prime Minister of Jamaica. Over the past 60 years, under the strong leadership of Jamaican leaders and arduous efforts of Jamaican people, Jamaica has been making big progress in socioeconomic development, constantly moving forward its cause in the fields of science, education, culture, health and sports, continuously improving people’s living standards, and playing an active and important role in international and regional affairs.

As a Chinese old saying goes, “Feel happy for others’ joy and others will do the same”, Chinese people always sincerely feel happy for their friends’ happy and joyful events. As China’s good friend and partner, Jamaica will celebrate its Diamond Jubilee of Independence, and Chinese people will definitely share this great happiness and joy with brotherly and sisterly Jamaicans.

Currently, the world is witnessing a persistent and unchecked COVID-19 pandemic, accelerating changes unseen in a century and a period of turbulence and transformation globally. Faced by unprecedented challenges, countries around the world are looking for answers and humanity needs to make the right choice. Under such circumstances, the international community should strengthen solidarity and cooperation, jointly meet challenges, and continue to promote the building of a community with a shared future for mankind so as to strive together for a brighter and better future for our world.

Diamond Jubilee of Independence provides a great opportunity for Jamaica to gather national strength and plan for future development. I sincerely wish that Jamaica would achieve the goal of “Reigniting a Nation for Greatness” and become “the place of choice to live, work, raise families and do business”.

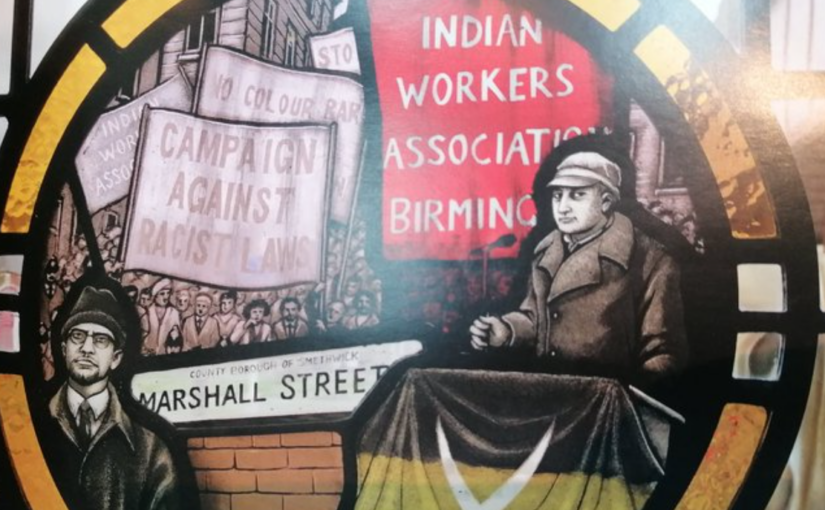

JIS: What are your thoughts on the resilience of the country, which included Chinese natives, to overcome slavery and now live as a free country?

Ambassador Chen: Slavery and colonialism have brought catastrophic sufferings to the world and left a very disgraceful page in human history. The days when Western colonists could do whatever they want have gone. However, we must also realize that the colonialist thinking and its derivative power politics and bullying are still manifested in various forms in international relations, which are still severely impacting the normal international order and seriously undermining the sovereignty, security, and development interests as well as political, economic and social stability of relevant countries. The international community still has a long way to go to completely eliminate the impacts of slavery and colonialism.

There is a proverb in Jamaica, which goes “Wi likkle, but wi tallawah”. China also always upholds that all countries are equal, regardless of their size. The history of Jamaica’s fight against the colonial rule and slavery was laudable and emotionally moving. The braveness, resilience and wisdom shown by Jamaican people in the fight is very impressive and admirable. China had similar history with Jamaica in modern times when both countries were invaded and suppressed by Western colonialists for a long time and both countries faced same tasks of seeking independence of the nation, prosperity of the country and happiness of the people. Similar history makes our two countries easier to understand and support each other.

In 1949, under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the People’s Republic of China was established. China has completely expelled the forces of Western imperialists in China, and the Chinese people has truly become the master of the country since then. Under the strong leadership of the CPC, China has successfully embarked on a development path that suits its national conditions, namely the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics, and has achieved the tremendous transformation from standing up and growing prosperous to becoming strong. China is now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. I wish Jamaica, under the leadership of Prime Minister Andrew Holness and with joint efforts of Jamaican people, would take the 60th anniversary of Independence as an opportunity to find a development path that suits Jamaica’s national conditions so as to achieve better and faster development.

JIS: Could you briefly speak on why China considers its relationship with Jamaica to be so important?

Ambassador Chen: Jamaica is the largest English-speaking country in the Caribbean region with great influence. China and Jamaica established diplomatic relations on 21 November 1972, and Jamaica was among the first several Caribbean countries to establish diplomatic relations with China. Over the past 50 years, under the strategic guidance of the leaders of our two countries, China-Jamaica relations maintain steady and sound development. During his visit to China in 2019, Prime Minister Andrew Holness, together with President Xi Jinping agreed to elevate the bilateral relations to strategic partnership. Since then, bilateral relations have been enjoying accelerated development. Over the past 50 years, China and Jamaica has been supporting each other on major issues involving each other’s core interests. China highly appreciates Jamaica’s consistent adherence to the one-China principle.

China-Jamaica relations is always at the forefront in the Caribbean region. Jamaica was the first Caribbean country to establish strategic partnership with China, and the first Caribbean country to sign the cooperation plan with China on jointly promoting the Belt and Road cooperation. The Confucius Institute at Mona Campus of the University of the West Indies (UWI) was the first Confucius Institute in English-speaking countries in the Caribbean region. Both history and realities prove that China and Jamaica are good brothers supporting each other, good friends going through ups and downs, and good partners seeking common development.

The steady and sound development of China-Jamaica relations brings many tangible benefits to our two countries and two peoples. The China-aid new headquarter of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade of Jamaica, the Chinese Garden at the Hope Royal Botanic Gardens and the Confucius Institute at Mona Campus of the UWI have been the witnesses and symbols of China-Jamaica friendship and cooperation. The China-aid Jamaica Western Children’s Hospital currently under construction, and the Montego Bay Perimeter Road Project, South Coast Highway Project as well as the JISCO Alpart Bauxite Upgrading and Expanding Project contracted or invested by Chinese enterprises will improve medical services, strengthen infrastructure construction, create more jobs and promote economic growth for Jamaica, and these projects will become the new symbols and landmarks of mutually-beneficial cooperation between our two countries. Jamaica’s reggae music, rum, Blue Mountain coffee provide Chinese people with enriched and diversified access to material and cultural experiences. We also welcome more Jamaica-featured products and services such as seafood, pork and tourism being exported to China so as to promote economic recovery and development of our two countries.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Jamaica. Our two countries will host a series of celebrating events, including co-hosting a reception celebrating our jubilee of diplomatic relations. I would like to take this interview as an opportunity to invite representatives from various circles in Jamaica to attend the reception and other celebrating events and jointly embark on a new journey of China-Jamaica relations then. China stands ready to work with Jamaica and jointly take the 50th anniversary of our diplomatic relations as an opportunity to enhance practical cooperation in various fields, pursue high-quality Belt and Road cooperation, and promote China-Jamaica strategic partnership to a higher level so as to bring more benefits to our two countries and two peoples.

JIS: Do you think the Chinese community in Jamaica, also acknowledges and will celebrate the nation’s independence?

Ambassador Chen: I noticed the motto on Jamaica’s national emblem upon my arrival of this country, which reads “out of many, one people”. This saying vividly shows that Jamaica is a multinational country, or a “melting pot”.

As a matter of fact, the first group of Chinese arrived in Jamaica more than 160 years ago, following whom more and more Chinese nationals came. They overcame various challenges and difficulties and actively integrated themselves into Jamaican society and have made important contributions to Jamaica’s economic, social and cultural development. With family ancestry from China, they also act as ambassadors between China and Jamaica and make their own contributions to promoting China-Jamaica relations, deepening bilateral practical cooperation and consolidating the traditional friendship between our two countries.

Today, Chinese Jamaicans have become an important part of the multinational Jamaica. As other Jamaicans, they live and study across the country and work in various fields, promoting the development of their mother country in their own ways. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Chinese communities in Jamaica donated a large number of medical supplies and items to the Jamaican government and people, supporting Jamaica’s fight against the pandemic. I believe that, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of Independence, Chinese communities in Jamaica would take an active part in the celebration activities in various manners.

JIS: How will you celebrate with the country during “Emancipendence” week?

Ambassador Chen: “Emancipendence” week is a very important festival for Jamaica and its people. Chinese President Xi Jinping, Premier Li Keqiang, Sate Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi will send Message of Congratulation to the Governor General, the Most Hon. Sir Patrick Allen, Prime Minister, the Most Honourable Andrew Holness and Minister of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, the Honourable Kamina Johnson Smith respectively to congratulate Jamaica’s 60th anniversary of Independence.

I myself will also contribute a signature article to send my own congratulatory messages to Jamaican people and share the happiness of this festival. In addition, I will watch celebration activities through television and Internet, and I would probably attend some activities in person. I believe this is a valuable chance to have a taste of the colorful and unique history and culture of Jamaica.

JIS: Any China’s future plans that you would like to mention at this time which includes mutual benefit between the two countries?

Ambassador Chen: As developing countries, both China and Jamaica face the task of achieving people-centered development and delivering an enjoyable life to our people. Development is the “master key” to solving all problems. Jamaica has already been involved in the Belt and Road Initiative. China and Jamaica have conducted win-win cooperation and yielded fruitful results in various fields such as economic and trade and infrastructure construction. Recently, Prime Minister Andrew Holness emphasized the necessity and importance of infrastructure construction at the Ground-Breaking Ceremony of the Montego Bay Perimeter Road Project.

Last September, President Xi Jinping proposed the Global Development Initiative (GDI), calling for a more robust, greener and more balanced global development. In July this year, China-Caribbean Development Center was established in my hometown Shandong Province. The Center aims to make the best of the geographical advantages of Shandong Province as a coastal province and promote cooperation between China and Caribbean countries in agriculture, logistics, infrastructure construction, information technology so as to seek common development by fully leveraging our respective strengths.

We welcome Jamaica’s participation in the Global Development Initiative and explore more cooperation in areas such as poverty alleviation, food security, COVID-19 response, climate change and green development, industrialization, digital economy and connectivity. We also welcome Jamaica to enhance its cooperation with the China-Caribbean Development Center. By doing these, Jamaica could allocate more resources for and inject stronger impetus into its socioeconomic development. The Chinese Embassy in Jamaica will play its role of a bridge, promoting practical cooperation in related areas and bring more benefits to our two countries and two peoples.

We also welcome more media friends to pay more attention to and increase coverage on the Global Development Initiative and the China-Caribbean Development Center in order to jointly create a positive atmosphere that promotes mutually-beneficial cooperation between China and Jamaica.

The second half of this year will witness the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Jamaica and we will hold a series of celebration activities. We will fully implement the strategic guidance of the leaders of our two countries and jointly usher in a bright future for China-Jamaica strategic partnership. The CPC will also convene its 20th National Congress, which will offer a panoramic prospect of the two-stage strategic plan for China’s drive to build a great modern socialist country in all respects, and will in particular lay out plans for the strategic missions and major measures in the next five years. More steady steps are to be made by Chinese people under the leadership of the CPC to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. A rich, strong, open and prosperous China will bring more opportunities to Jamaica and the rest of the world. I firmly believe that the future of China-Jamaica strategic partnership would be even brighter and the traditional friendship between our two peoples would be even more profound!