China recently marked the 120th anniversary of the birth of former leader Deng Xiaoping, with the centrepiece being a keynote speech by Xi Jinping.

The anniversary also saw the publication of an important article by Qu Qingshan, the President of the Central Party History and Literature Research Institute of the Communist Party of China (CPC), which reviewed in detail the political background, methodology and historical significance of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in drafting the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China”, which was adopted by the CPC in 1981 and evaluated in particular the role of Comrade Mao Zedong, the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought and the experience of the Cultural Revolution.

Qu notes that: “More than 40 years have passed, and with the complex and profound changes in the domestic and international situation, Deng Xiaoping’s extraordinary courage, superb wisdom and political foresight in making this major strategic decision have become increasingly evident… Whether from the perspective of the time or today, the series of major issues that the Resolution was to solve, especially the evaluation of Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, are major issues concerning the development direction of the Party and the country and the future and destiny of socialism and are ‘major international and domestic political issues.'”

Having noted the existence of various incorrect views, emanating from both the right and the ‘left’ in the period leading up to the drafting of the resolution, along with Deng’s insistence on dealing with issues at the right time and in an orderly fashion, the author sums up his viewpoint as follows:

“How to thoroughly negate the erroneous practices and theories of the Cultural Revolution and resolutely resist the erroneous trend of negating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought is a major test of our Party’s leadership ability, political determination, ruling status and international image. From a domestic perspective, if this issue is handled well, it will unify the thinking of the entire Party, the entire army and the people of all ethnic groups in the country, consolidate the political situation of stability and unity, and enable the Party and the country to move forward in the correct political direction; if it is not handled well, it will cause great chaos, ruin the political situation of stability and unity, and the Party may even mess itself up and collapse. From an international perspective, if this issue is handled well, it will be conducive to the unity of political parties and organisations that support the Communist Party of China and China’s socialist cause, to the unity of the people of the Third World, and to the cause of human progress; if it is not handled well, it may bring about a series of serious problems.”

Qu notes that three general guiding ideologies were proposed, among which the most core, important, fundamental and crucial one was to establish Mao Zedong’s historical status and to uphold and develop Mao Zedong Thought. He quotes Deng as saying: “The evaluation of Comrade Mao Zedong and the exposition of Mao Zedong Thought are not just issues related to Comrade Mao Zedong personally but are inseparable from the entire history of our party and our country.” “This is not just a theoretical issue, but especially a political issue, a major international and domestic political issue.”

A very important section towards the end of the article makes a comparative analysis with previous historical experience of the international communist movement and relates this to the contemporary prospects for socialism in China and the world:

“Today, more than 40 years later, we can gain a lot of inspiration, wisdom and strength from looking back at the history of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in formulating the Resolution at a critical turning point. In particular, by looking back at the road we have travelled, comparing the roads of others, and looking ahead to the road ahead, we can more deeply understand the great significance and far-reaching impact of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in formulating the Resolution, and we can more deeply appreciate Deng Xiaoping’s broad mind and foresight as a great Marxist, a great proletarian revolutionary, politician, military strategist, and diplomat.

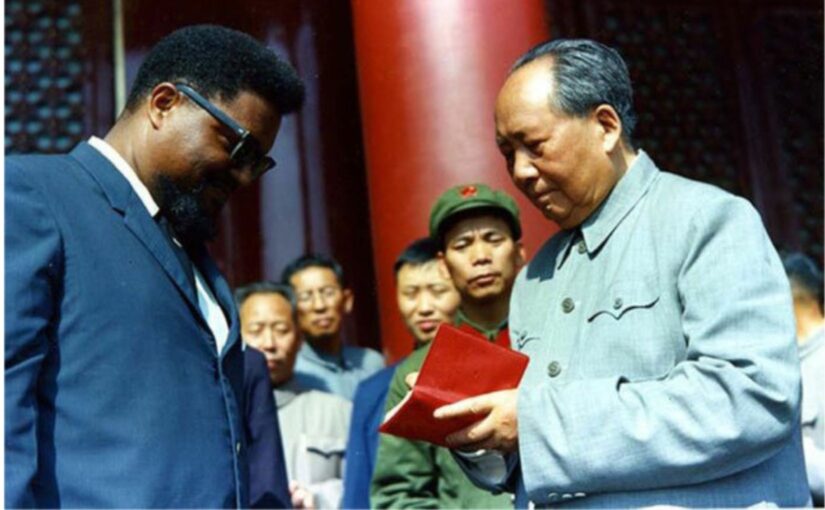

“In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Soviet Union disintegrated, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union collapsed, and Eastern Europe underwent drastic changes, causing serious setbacks to world socialism. The source of this tragedy can be traced back to the secret report of Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which completely denied Stalin. Mao Zedong said: ‘I think there are two ‘swords’: one is Lenin and the other is Stalin. Now, the Russians have lost the sword of Stalin. … Have some Soviet leaders also lost some of the sword of Lenin? I think they have lost quite a lot.” Khrushchev’s secret report caused serious ideological confusion in the world socialist camp at that time. The subsequent development of events was just as Mao Zedong had predicted. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union went from completely denying Stalin to denying and attacking Lenin, denying and attacking Marx and Engels, and denying the entire Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It completely distorted and vilified the entire history of the Soviet Union’s socialist revolution and construction, and fundamentally disintegrated all the supports of the socialist edifice. As a result, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, as big a party as it was, was scattered, and the Soviet Union, as big a socialist country as it was, fell apart.

“Fortunately, the Communist Party of China has always been extremely serious and solemn in its attitude towards its own history and its leaders, showing the style of a truly mature Marxist party. Imagine if Deng Xiaoping had not resisted the erroneous trend of negating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, would our party still be able to stand? Would our country’s socialist system still be able to stand? It would not be able to stand, and if it did not stand, there would be chaos in the world. General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out: ‘If the leadership of the Communist Party of China and our socialist system also collapsed in the domino-like changes of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Soviet Communist Party, and the upheaval in Eastern Europe, or failed for other reasons, then the practice of socialism might have to wander in the darkness for a long time, and would have to wander around the world as a spectre as Marx said.’ China had Deng Xiaoping’s foresight and courageous decision-making at a critical moment, and correctly solved the major political issue of evaluating the historical status of Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, which was related to the future and destiny of the party and the country, and avoided making a ‘historical mistake’, thus laying a solid foundation for the unity of the party, the stability of the country, and the long-term development of the cause of the party and the people. Following the correct direction guided by Deng Xiaoping, our Party not only withstood the impact and stood the test when world socialism fell into a low tide, and held up and stabilised the banner of socialism in the world, but also promoted socialism with Chinese characteristics into a new era, making the historical evolution and competition of the two ideologies and two social systems in the world undergo a profound transformation that is beneficial to Marxism and socialism, and becoming the mainstay of the revitalisation of world socialism. Looking back on the past and comparing the present, it is touching and thought-provoking!”

We reprint below the full text of Qu Qingshan’s article, which deserves to be read carefully and in full. It was originally published in Study Times on August 21. The below version was machine translated from the reprint of the article in The Paper and has been sub-edited by us.

Courage, wisdom and vision: Deng Xiaoping’s major contribution to the formulation of the Party’s second historical resolution

Qu Qingshan, President of the Central Party History and Literature Research Institute

This year marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Comrade Deng Xiaoping. Learning and carrying forward Comrade Deng Xiaoping’s revolutionary spirit and noble demeanour have great practical significance in inspiring us to comprehensively promote the construction of a strong country and the great cause of national rejuvenation through Chinese-style modernisation. Deng Xiaoping made immortal contributions to the cause of the Party and the people throughout his life. One of his great historical contributions was to guide our Party in formulating the “Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of our Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China” (hereinafter referred to as the Resolution), which played a role in raising the flag, setting the direction, turning the tide, and making the final decision at a critical juncture related to the future and destiny of the Party and the country. More than 40 years have passed, and with the complex and profound changes in the domestic and international situation, Deng Xiaoping’s extraordinary courage, superb wisdom and political foresight in making this major strategic decision have become increasingly evident.

Deng Xiaoping’s extraordinary courage in leading the formulation of the Resolution was reflected in his decisive decision-making at a critical historical turning point.

History can often be seen more clearly after the passage of time. The drafting of the Resolution is of great importance because it reviews the history of the Party before the founding of New China, summarises the historical experience of socialist revolution and construction, and evaluates some major events and important figures. In particular, it correctly evaluates Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, distinguishes right from wrong, corrects the wrong views of the ‘left’ and the right, unifies the thinking of the whole Party, and has a significant impact on promoting the Party to unite and look forward, and better promote reform and opening up and socialist modernisation. Whether from the perspective of the time or today, the series of major issues that the Resolution was to solve, especially the evaluation of Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, are major issues concerning the development direction of the Party and the country and the future and destiny of socialism and are “major international and domestic political issues.”

Under what historical background did the Resolution come into being? In general, it came into being during the historical process of emancipating the mind and rectifying the wrongs after the end of the Cultural Revolution. At a critical historical juncture when the Party and the country were faced with a questionable path, Deng Xiaoping began by rectifying the ideological line, emphasising that seeking truth from facts was the essence of Mao Zedong Thought, and clearly opposed the erroneous view of “two whatevers”. He supported and led the discussion on the criterion of truth, promoted rectification of the wrongs in all aspects, and promoted the ideological emancipation of the whole Party. Before and after the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party, there were calls within and outside the Party to summarise and evaluate the history of the Party after the founding of New China, especially Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong Thought, and the Cultural Revolution.

It is crucial to correctly understand and grasp the problem, and it is equally important to choose the right time to solve the problem. In the face of calls from inside and outside the Party, whether and when to formulate the Resolution is related to the future and destiny of the Party and the country, and also tests the political courage of the helmsman of the Party and the people’s cause. When the time is not ripe and the conditions are not met, insisting on doing it, rushing and acting rashly will only backfire; when the situation changes and the conditions are met, prevaricating and hesitating will also miss the opportunity and bring serious consequences. Deng Xiaoping’s extraordinary courage as a Marxist politician is concentrated in the fact that he should not rush to formulate the Resolution when it is not time, and he should not wait when it is time to formulate the Resolution.

Don’t rush. Deng Xiaoping was always good at thinking about problems from a holistic perspective and making strategic decisions at critical moments. On the issue of formulating the Resolution, he believed that the strategic issue related to the overall situation before and after the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party was to achieve a strategic shift in the focus of the Party and the country’s work. The time was not yet ripe to evaluate Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong Thought and the Cultural Revolution. In order to maintain stability and unity, this issue should not be touched upon for the time being. At the Central Working Conference before the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party, when many cadres demanded to seriously summarise the painful lessons of the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping advocated that the summary of the Cultural Revolution should not be carried out immediately. He pointed out:

“The Cultural Revolution has become a stage in the development of our country’s socialist history. It is necessary to summarise it, but there is no need to rush. To make a scientific evaluation of such a historical stage, we need to do serious research work. Some things will take a longer time to fully understand and evaluate. At that time, we may be able to explain this period of history better than we do today.”

The Communiqué of the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party also emphasised that it is necessary to summarise the Cultural Revolution as experience and lessons at an appropriate time, but it should not be done in a hurry. At the Party’s theoretical work retreat in 1979, some comrades expressed the hope that the Party Central Committee would summarise the 30 years of history since the founding of New China as soon as possible, and make a resolution on several historical issues since the founding of New China, just as the “Resolution on Several Historical Issues” was made at the Seventh Plenary Session of the Sixth Central Committee of the Party in 1945. In response, Deng Xiaoping focused on elaborating on the fundamental ideological and political issue of why the Four Cardinal Principles must be upheld in China, which actually showed a clear position on Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought.

We can’t wait. With the full implementation of the rectification of chaos and the promotion of reform and opening up, two erroneous tendencies emerged in the discussion of Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong Thought and the Cultural Revolution. One tendency was that some people were bound by “leftist” thinking and showed a certain degree of misunderstanding and even resistance to the line, principles and policies of the Party since the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee; the other tendency was that a very small number of people took advantage of the opportunity of the Party’s rectification of chaos to distort the slogan of “emancipating the mind” and extremely exaggerate the mistakes made by the Party, attempting to deny the leadership of the Communist Party of China, deny the socialist system, and deny Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought. Not only were people inside and outside the Party very concerned about how the Party Central Committee would evaluate Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong Thought and the Cultural Revolution, but foreign countries were also very concerned about this issue and raised various suspicions. These situations showed that the issue of evaluating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought is a major, sensitive issue with international influence, and it had become increasingly urgent. How to thoroughly negate the erroneous practices and theories of the Cultural Revolution and resolutely resist the erroneous trend of negating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought is a major test of our Party’s leadership ability, political determination, ruling status and international image. From a domestic perspective, if this issue is handled well, it will unify the thinking of the entire Party, the entire army and the people of all ethnic groups in the country, consolidate the political situation of stability and unity, and enable the Party and the country to move forward in the correct political direction; if it is not handled well, it will cause great chaos, ruin the political situation of stability and unity, and the Party may even mess itself up and collapse. From an international perspective, if this issue is handled well, it will be conducive to the unity of political parties and organisations that support the Communist Party of China and China’s socialist cause, to the unity of the people of the Third World, and to the cause of human progress; if it is not handled well, it may bring about a series of serious problems.

In response to the changing situation, in 1979, Deng Xiaoping proposed in the drafting of Comrade Ye Jianying’s speech at the celebration of the 30th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China that this speech should summarise the past 30 years, especially explain the Cultural Revolution, have some new content, and be able to speak at a new level. Ye Jianying’s evaluation of Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong Thought and the Cultural Revolution in the celebration speech received great attention from inside and outside the party and aroused a good response. However, this summary was preliminary after all, and it was impossible to elaborate on the important issues of concern to the party and others in detail. Therefore, the voices inside and outside the party for a formal resolution on historical issues to be made as soon as possible got louder and louder. At this time, Deng Xiaoping evaluated the situation and made a comprehensive judgment, and believed that the time for formulating the Resolution was ripe and could not wait any longer, otherwise it would affect the implementation of the line, principles and policies of the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party. He made a decisive decision and asked to start drafting the Resolution based on Ye Jianying’s celebration speech. He stressed: “With the National Day speech, it will be easier to write a historical resolution. Take the speech as an outline and consider making it more specific and in-depth.” In response to the opinion of some people that the time and conditions were not yet ripe and that there was no rush to make a resolution, hoping to resolve it after the 12th National Congress of the Party or even later, he pointed out: “We must resolve it now, and cannot let future generations resolve it because they do not understand the entire history.” “In the past, some comrades have also raised the question of whether this resolution should be made in a hurry? No, everyone is waiting. Domestically, everyone inside and outside the Party is waiting. If you don’t come up with something, there will be no unified view on major issues. The international community is also waiting. People look at China and doubt our stability and unity, including whether this document can be produced, whether it is produced early or late. Therefore, it cannot be delayed any longer, otherwise it will be disadvantageous.”

Deng Xiaoping’s superb wisdom in leading the formulation of the Resolution is reflected in the creative proposal of the guiding ideology, basic principles, important requirements and scientific methods for drafting the Resolution.

The Resolution was drafted under the leadership of the second generation of the Party’s central leadership collective with Comrade Deng Xiaoping as the core. Deng Xiaoping presided over the drafting of the Resolution from beginning to end and played a decisive role in the promulgation of the Resolution. He proposed the guiding ideology of the Resolution, designed the framework of the Resolution, determined the evaluation of major events, important meetings, and important figures in the Resolution, and made decisions on some major historical and theoretical issues in the Resolution. From March 1980 to June 1981, Deng Xiaoping held 17 talks on the drafting of the Resolution, clarifying the direction and setting the tone for the drafting of the Resolution. Among them, nine talks were included in the Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping. It can be said that Deng Xiaoping’s series of major ideological viewpoints and strategic ideas with overall significance provided a fundamental basis for the formulation of the Resolution.

Three general guiding ideologies were proposed, among which the most core, important, fundamental and crucial one was to establish Mao Zedong’s historical status and to uphold and develop Mao Zedong Thought. In March 1980, Deng Xiaoping proposed three general guiding ideologies for drafting the Resolution when talking with the responsible comrades of the Central Committee, which pointed out the correct direction for the drafting of the Resolution. “First, establish Comrade Mao Zedong’s historical status and uphold and develop Mao Zedong Thought. This is the most core one.” “Second, we must conduct a realistic analysis of the major events in the history of the country over the past 30 years, which are correct and which are wrong, including the merits and demerits of some responsible comrades, and make fair evaluations.” “Third, through this resolution, we will make a basic summary of the past.” He emphasised in particular: “The most important, fundamental and crucial one is still the first one.” Deng Xiaoping constantly expounded on these three principles in relevant speeches and talks, especially on the first one, he repeatedly talked about it on various occasions, and conducted serious and patient persuasion and education on various vague understandings and mistakes. He pointed out: “The evaluation of Comrade Mao Zedong and the exposition of Mao Zedong Thought are not just issues related to Comrade Mao Zedong personally but are inseparable from the entire history of our party and our country.” “This is not just a theoretical issue, but especially a political issue, a major international and domestic political issue. If this part is not written or written poorly, the entire resolution would be worse off.” A member of the drafting group recalled: “If (Comrade Deng Xiaoping) had not unswervingly adhered to this guiding ideology, it would have been difficult for the Resolution to achieve the current effect, receive such good reviews, and would have made it difficult for all party comrades and people of all ethnic groups in the country to achieve unity in thought and understanding, and unite and look forward on the basis of the Resolution.”

Put forward the basic principle of “broad rather than detailed”. How should the Resolution be written? One of the basic principles established by Deng Xiaoping is “broad rather than detailed”. He pointed out: “Generally speaking, historical issues should be treated in a rough and general way, not too detailed.” “This summary should be rough rather than detailed. The purpose of summarising the past is to guide everyone to unite and look forward. We will strive to clarify the thoughts and reach a consensus among the party and the people after the adoption of the resolution, and the discussion of major historical issues will basically end here.” “We cannot dwell on the past but must direct everyone’s thoughts and attention to the four modernisations.” Guided by this basic principle, the Resolution gives a relatively general and rough description of the party’s history, especially the party’s history since the founding of New China. It does not seek to be comprehensive, nor does it dwell on minor details and minor issues. This basic principle is in line with the research methods of contemporary history, because the Resolution involves many parties and many important policies and guidelines, and the evaluation of them will inevitably affect the current overall situation, so it must be cautious. This basic principle is also in line with the characteristics and laws of historical cognition, because many historical facts are not long ago, and the truth of the historical facts needs to be further clarified and our understanding needs to be continuously improved.

Put forward the important requirement of adhering to historical materialism. Deng Xiaoping emphasised: “We are historical materialists. The study and solution of any problem cannot be separated from certain historical conditions.” “We can only affirm what should be affirmed and negate what should be negated in a realistic way.” “When evaluating people and history, we must advocate a comprehensive and scientific viewpoint and prevent one-sidedness and emotionalism.” Deng Xiaoping said this and did it. On the important issue of evaluating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping did not proceed from personal feelings, but from the overall situation of the work of the Party and the country, from the history and cause of the Party, and from the fundamental and long-term interests of the whole Party. This is particularly touching and admirable. Deng Xiaoping pointed out: “Although our party has made some major mistakes in history, including the thirty years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and even made major mistakes such as the Cultural Revolution, our party has finally succeeded in the revolution. China’s position in the world has greatly improved since the founding of the People’s Republic of China.” He demanded “to evaluate the “Cultural Revolution” realistically and appropriately, and to evaluate the merits and demerits of Comrade Mao Zedong. Under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping, the Resolution adheres to the viewpoint of historical materialism, analyses the evaluation of Mao Zedong in the historical conditions of his time and society, correctly analyses the mistakes and twists and turns the Party experienced on its road ahead, and discusses Mao Zedong’s historical status and the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought in a realistic and appropriate manner. The conclusions drawn have withstood the test of history, practice and the people.

Propose scientific methods for evaluating historical figures. Focusing on the core issue of evaluating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, Deng Xiaoping proposed many scientific methods with strong guiding significance. For example, we should distinguish the primary and secondary between Mao Zedong’s achievements and mistakes. When meeting with Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, he said: “We will affirm that Chairman Mao’s achievements are the first and his mistakes are the second.” “We should speak realistically about Chairman Mao’s mistakes in his later years.” “From the perspective of the feelings of the Chinese people, we will always commemorate him as the founder of our party and country.” The portrait of Chairman Mao on Tiananmen Square “should be preserved forever.” For example, distinguishing Mao Zedong Thought from the mistakes of Mao Zedong in his later years, he pointed out: “Mao Zedong Thought should be distinguished from the mistakes of Comrade Mao Zedong in his later years, so as to avoid a lot of confusion. Of course, this does not mean that Comrade Mao Zedong did not express correct opinions in his later years.” For example, the most important reason for Mao Zedong’s mistakes was the system problem. He pointed out: “All problems cannot be attributed to personal qualities” and “even people with good qualities cannot avoid mistakes under certain circumstances.” He stressed: “A good system can prevent bad people from running rampant, while a bad system can prevent good people from doing good things to their full potential, and even turn them into the opposite. Even a great figure like Comrade Mao Zedong was seriously affected by some bad systems, which caused great misfortune to the Party, the country and himself.” For example, wrong opinions must be resisted and guided. After the draft of the Resolution was formed, in response to the tendency of completely denying Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought that emerged in the “Four Thousand People Discussion”, he “strongly rejected wrong opinions” and pointed out: “There are many good opinions in the discussion, which should be accepted. Some opinions cannot be accepted,” and “We must bite the bullet and resist the wrong opinions of some comrades on some issues.” Because Deng Xiaoping demonstrated the Party Central Committee’s rock-solid position and uncompromising attitude on the most controversial, most divergent, and most fundamental and core issues at the time, this provided the most important conditions for the Resolution to eliminate interference and succeed.

In short, Deng Xiaoping’s superb political wisdom provided the general ideas, general principles and general compliance for the drafting of the Resolution, and especially played the role of a stabilising force on major key issues. It was under the guidance of the guiding ideology, basic principles, important requirements and scientific methods proposed by Deng Xiaoping that the drafting of the Resolution firmly grasped the key of scientifically evaluating Mao Zedong’s historical status and the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought, summed up the party’s major historical events and important lessons, distinguished right from wrong, unified thoughts, enhanced unity, and promoted the development of the party and the people’s cause. The formulation of the Resolution marked the successful completion of the party’s rectification of the chaos in the guiding ideology.

Deng Xiaoping’s political foresight in leading the formulation of the Resolution was reflected in determining the correct direction for the development of the Party and the country, guiding the whole Party to unite and look forward, and creating a new situation for the development of the cause.

Deng Xiaoping pointed out: “Summarising the past is to guide everyone to unite and look forward.” Summarising history is looking back, but looking back is to better look forward and to better open up the future. This clear orientation of “looking forward” is not only reflected in the guiding ideology and essence of the Resolution, but also in the timing and venue of passing historical resolutions. The Resolution was passed at the Sixth Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Party, just as Deng Xiaoping hoped: “Strive to pass this resolution at the Central Plenary Session before the Twelfth National Congress, so that there will be a unified understanding of past issues and a conclusion. The Twelfth National Congress will speak new words and talk about looking forward.”

Under the guidance of Deng Xiaoping, the Resolution, based on summarising the positive and negative experiences since the founding of New China, summarised the main points of the correct road of socialist modernisation construction that the Party has gradually established since the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party, which is suitable for the country’s national conditions, in ten aspects. This is actually a theoretical summary of the correct road of socialist modernisation construction that has been opened up since the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Party, which is suitable for the country’s national conditions, and preliminarily raised the question of what kind of socialism to build in China and how to build socialism. In other words, the Resolution actively explored the major historical issue of establishing the correct road of socialist modernisation construction in the country in accordance with the new reality and development requirements, showing our Party’s strong determination to follow the trend of the times and the people’s wishes and bravely open up a new road to build socialism. It made full preparations for the 12th National Congress of the Party to put forward the major proposition of “building socialism with Chinese characteristics” and to create a new situation in reform and opening up and socialist modernisation and laid an important foundation for the creation of the road of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out: “Comrade Deng Xiaoping guided our party to systematically summarise the historical experience since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, solved two interrelated major historical issues: scientifically evaluating Comrade Mao Zedong’s historical status and the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought, and establishing the correct path for China’s socialist modernisation construction based on new realities and development requirements. He completely negated the erroneous practices and theories of the Cultural Revolution, resolutely resisted the erroneous trend of thought that negated Comrade Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought and determined the correct direction for the development of the Party and the country.” This is a scientific summary and high evaluation of Deng Xiaoping’s historical achievements in leading the formulation of the Resolution. It should be noted that the two interrelated historical issues of scientifically evaluating Mao Zedong’s historical status and the scientific system of Mao Zedong Thought and establishing the correct path for China’s socialist modernisation construction based on new realities and development requirements are two aspects of a general issue. If any of the historical issues is not resolved, the resolution of the other historical issue is out of the question. Fundamentally speaking, these two historical issues have profound internal consistency, because the great practice of revolution, construction, and reform led by our party is a historical process of continuous struggle. Deng Xiaoping emphasised many times: “After the Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee, we restored the correct things of Comrade Mao Zedong, that is, accurately and completely studied and applied Mao Zedong Thought. The basic points are still the same. In many ways, we are still doing what Comrade Mao Zedong had proposed but did not do, correcting what he opposed wrongly, and doing well what he did not do well. We will still do this for a considerable period of time in the future. Of course, we have also developed, and we will continue to develop.” “We are carrying out reform and opening up, focusing our work on economic construction. We have not abandoned Marx, Lenin, or Mao Zedong. We cannot abandon our ancestors!”

Today, more than 40 years later, we can gain a lot of inspiration, wisdom and strength from looking back at the history of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in formulating the Resolution at a critical turning point. In particular, by looking back at the road we have travelled, comparing the roads of others, and looking ahead to the road ahead, we can more deeply understand the great significance and far-reaching impact of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in formulating the Resolution, and we can more deeply appreciate Deng Xiaoping’s broad mind and foresight as a great Marxist, a great proletarian revolutionary, politician, military strategist, and diplomat.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Soviet Union disintegrated, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union collapsed, and Eastern Europe underwent drastic changes, causing serious setbacks to world socialism. The source of this tragedy can be traced back to the secret report of Khrushchev at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which completely denied Stalin. Mao Zedong said: “I think there are two ‘swords’: one is Lenin and the other is Stalin. Now, the Russians have lost the sword of Stalin. … Have some Soviet leaders also lost some of the sword of Lenin? I think they have lost quite a lot.” Khrushchev’s secret report caused serious ideological confusion in the world socialist camp at that time. The subsequent development of events was just as Mao Zedong had predicted. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union went from completely denying Stalin to denying and attacking Lenin, denying and attacking Marx and Engels, and denying the entire Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It completely distorted and vilified the entire history of the Soviet Union’s socialist revolution and construction, and fundamentally disintegrated all the supports of the socialist edifice. As a result, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, as big a party as it was, was scattered, and the Soviet Union, as big a socialist country as it was, fell apart.

Fortunately, the Communist Party of China has always been extremely serious and solemn in its attitude towards its own history and its leaders, showing the style of a truly mature Marxist party. Imagine if Deng Xiaoping had not resisted the erroneous trend of negating Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, would our party still be able to stand? Would our country’s socialist system still be able to stand? It would not be able to stand, and if it did not stand, there would be chaos in the world. General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out: “If the leadership of the Communist Party of China and our socialist system also collapsed in the domino-like changes of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Soviet Communist Party, and the upheaval in Eastern Europe, or failed for other reasons, then the practice of socialism might have to wander in the darkness for a long time, and would have to wander around the world as a spectre as Marx said.” China had Deng Xiaoping’s foresight and courageous decision-making at a critical moment, and correctly solved the major political issue of evaluating the historical status of Mao Zedong and Mao Zedong Thought, which was related to the future and destiny of the party and the country, and avoided making a “historical mistake”, thus laying a solid foundation for the unity of the party, the stability of the country, and the long-term development of the cause of the party and the people. Following the correct direction guided by Deng Xiaoping, our Party not only withstood the impact and stood the test when world socialism fell into a low tide, and held up and stabilised the banner of socialism in the world, but also promoted socialism with Chinese characteristics into a new era, making the historical evolution and competition of the two ideologies and two social systems in the world undergo a profound transformation that is beneficial to Marxism and socialism, and becoming the mainstay of the revitalisation of world socialism. Looking back on the past and comparing the present, it is touching and thought-provoking!

History is the best textbook, the best teacher, and the best sobering agent. The historical process and great achievements of Deng Xiaoping’s leadership in formulating the Resolution will always illuminate our party’s great journey of learning from history and creating the future. We must unite more closely around the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core, further deeply understand the decisive significance of the “two establishments”, enhance the “four consciousnesses”, strengthen the “four self-confidences”, and achieve the “two safeguards”, and strive to comprehensively promote the construction of a strong country and the great cause of national rejuvenation with Chinese-style modernisation!