This article by Jenny Clegg – a revised and enlarged version of a three-part series originally published in the Morning Star (part 1 | part 2 | part 3) – provides a broad overview of China’s political trajectory in the present era.

Jenny takes on the media caricature of Xi Jinping as an “authoritarian” leader, analysing his political development over the course of several decades, noting in particular his longstanding commitment to combating climate change, his dedication to poverty alleviation, and his belief that China should shift away from using GDP growth as the central metric of economic success. As CPC General Secretary and China’s President, the most prominent aspects of Xi’s record have been the extremely rigorous (and popular) anti-corruption campaign; the success in eliminating extreme poverty; a major focus on environmental questions; and the centring of a common prosperity agenda that is already operating to reduce inequality and improve the conditions of the poor.

Sympathetic but not uncritical, the article provides valuable insights and a realistic assessment of China’s prospects for developing into a “modern advanced socialist country that is strong and prosperous” by the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (2049).

1. Who is Xi Jinping?

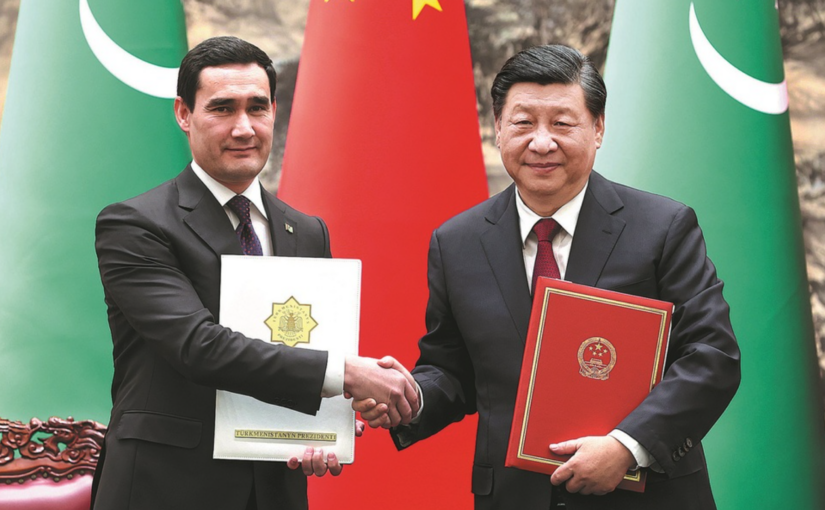

The Communist Party of China’s 20th Congress confirmed Xi Jinping as General Secretary for a third term. According to the mainstream media, China is lurching once again toward ‘one-man rule’ under the ‘thrice crowned’ leader. But what kind of rule will this be? China is the world’s second largest economy and the politics of its leader is of great consequence for the world.

So what are Xi’s politics? What has his leadership over the last 10 years meant for China and what direction does he intend the country to take over the next 5 years and beyond?

Xi’s political development

The son of a revolutionary hero who became a vice premier of China in the 1950s only to later fall victim to political turmoil in the Mao period,[1] Xi himself was a ‘sent down’ youth spending seven years from the age of 15 working in a poor community in China’s West. Serving for a time as a commune leader, he adopted the work style of ‘plain living and hard work’ – the ideal followed by the CPC from its earliest days.

Whilst these formative experiences moulded his core political outlook, it was through his work as Party Secretary of Zhejiang Province from 2002 to 2007 that a more concrete politics took shape.

Zhejiang is a commercialised province, one of those key Eastern seaboard areas which have driven the country’s hi-speed growth. After China joined the WTO in 2001, local cadres were exhorted to promote business, help new enterprises and court foreign investment, creating new jobs and opportunities.

But rapid industrialisation also brought increasing inequality, environmental degradation as well as corruption as the boundaries between politics and business blurred. Now in the senior ranks of Party leadership, one of some 3,000, Xi expressed his concerns in a series of articles in which he put great stress on the moral standards of the cadres and the need to prevent Party officials from solidifying into a privileged elite removed from the rest of society.

Power, he argued, was not a personal possession, to be used not for self-aggrandisement but for the public good. Grass roots levels were crucial – this was where the Party worked together with the people to build a better future. Emphasising the quality not just the quantity of growth – ‘not everything has to be done for GDP’; and the importance of the environment – ‘there is only one world and only one environment’ – Xi was paving a new way forward.[2]

Cleaning up the Party

By 2012, when Xi became Party leader, China had recovered rapidly after taking a serious hit in the 2008/9 world financial crisis, resuming the fast growth that had seen the economy more than double in the previous decade. It was up to him now to realise the previously set goals of achieving a ‘moderately prosperous society’ by 2020.

Xi’s first step was to refocus the Party on its high values of public service, launching a far-reaching anti-corruption campaign targeted at ‘tigers’ at the top as well as ‘flies’ at the bottom. His insistence that his immediate family should not undertake any business dealings struck a chord with people, gaining him much popularity.

A graduate in chemical engineering, with a PhD in Marxist legal theory, Xi was also a good communicator, a skill acquired during his years in the countryside, and the fact that he could put over his political message in an accessible manner, avoiding stilted rhetoric, also added to his popularity.

Determined to restore ideology to the heart of the Party, he encouraged Marxist study as well as wider Marxist intellectual debate, these not for the sake of theorising but in order to drive policy and practice forward.

His affirmation in 2013 of the role of the market as playing ‘a decisive role in the allocation of resources in the economy’ saw a widening of market reforms whilst a new emphasis on commercial law which, together with the wider establishment of enterprise-based Party committees, vastly improved business practice. From 2015, a massive infusion of government support reinforced the role of state-owned enterprises at the centre of economic policy.

Two particular advances of Xi’s first term were, on the domestic front, the 2016 Made In China Initiative which laid the basis of China’s technological upgrading to a higher stage of modernisation; and, of international consequence, the Belt and Road Initiative, setting out a new mode for China’s integration with the world community.

Continue reading China under Xi Jinping: putting politics in command