We are very pleased to republish this important article by Roland Boer, Professor of Marxist Philosophy in the School of Marxism at China’s Dalian University of Technology, and a member of our advisory group.

Professor Boer makes a detailed and systematic theoretical and comparative analysis of the economic reforms undertaken in China since the end of the 1970s and the earlier reforms carried out in a number of East European socialist countries, particularly the two countries whose reforms were most extensive – Yugoslavia, with its decentralised system of self-managed worker enterprises in a ‘labour-managed market economy’, developed following the country’s expulsion from the Cominform in 1948; and Hungary, which initiated its New Economic Mechanism (NEM) in 1968.

He notes that the results were very different. With the exception of Belarus, Eastern Europe devolved into capitalist “shock therapy”, whereas “China took its reforms to a point where we are now entering yet a new stage in socialist construction, based on the prosperity that has been achieved. Along the way, many lessons have been learned, concerning planning, markets, ownership and liberation of productive forces, and indeed how the relations and forces of production interact with one another during socialist construction. It is precisely in light of these experiences that a systematic comparison becomes possible.”

His comparison looks at four major aspects:

1) The de-linking of a market economy from a capitalist system, and the concomitant de-linking of a planned economy from a socialist system;

2) The question as to whether a market economy is a neutral instrument that can be used in any system, or whether it is a component that is shaped by the system of which it is a part;

3) Planning and markets within a socialist system;

4) The relationship between ownership of the means (and forces) of production and liberation of productive forces, and thus the interactions between relations and forces of production.

Boer notes that both Eastern Europe and China achieved rapid economic growth by adopting the centrally planned economic model in the years following the establishment of a socialist state. Indeed, in the case of China, he notes: “This was necessary at the time, not merely in terms of overcoming the devastating effects of semi-colonialism, feudal relics, and comprador capitalism, but also to get the economy moving from decades of revolutionary struggle and war. The results were stunning for a time, outstripping any other developing country.”

However, in both Eastern Europe and China, contradictions gradually mounted, leading to the search for a new economic paradigm. He further notes that whilst China took the road of economic reform later, it has also taken its reforms much further.

Boer poses the question of how one should define a market economy. In Eastern Europe it was seen as a mechanism, or neutral tool, but the author argues that China has taken “an important step beyond the instrumentalist position, in which a market is simply a neutral tool that can be used in different social systems. Instead, the institutional forms of market and planned economies are shaped, are determined in their nature, by the system in question.” Therefore, the institutional form becomes not “market socialism” but rather a “socialist market economy”. As a Chinese scholar cited by Boer observes: “There is no market economy institutional form that is independent of the basic economic system of society.”

Having analysed some of the factors that caused socialism in Eastern Europe to collapse but to prevail in China, Boer notes that: “In the midst of China’s stunning economic success, a spate of well-documented and widely-studied problems became apparent during the ‘wild 90s,’ and even into the early 2000s: declining conditions for workers and consequent unrest; illegal appropriation of collectively owned village lands; a growing gap between rich and poor regions; environmental degradation; ideological disarray, with proposals ranging from the recovery of Confucianism to bourgeois liberalisation; and a rift between the CPC and the common people, leading to corruption and lack of knowledge of Marxism even by leading cadres.”

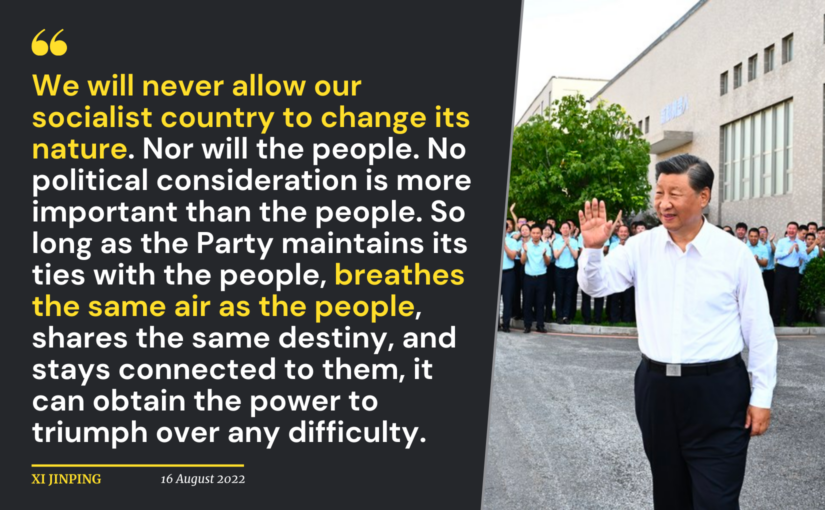

Tackling these issues has become the theme of the next, and current, stage of the Chinese revolution, since Xi Jinping assumed the leadership of the party in 2012. Boer argues that: “We can already begin to see clear results: about 800 million rural and urban workers have been lifted out of poverty, with almost 500 million now in a ‘middle-income’ group (and not a ‘middle class’); the gap between rich and poor has been decreasing now for about a decade; rural and urban workers are engaged in all aspects of China’s ever-strengthening socialist democratic system; in light of ecological civilisation, China has become a world leader in ‘green growth’; and the almost 100-million strong CPC is more united, more knowledgeable about Marxism, and more focused on the task ahead than at almost any time in its past.”

This is an extremely important article which deserves close study. It was originally published in the journal World Review of Political Economy (published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and produced and distributed by Pluto Journals).

Abstract: This study offers a comparative analysis of economic reforms in Eastern Europe and China. Some CMEA countries—especially Yugoslavia and Hungary—undertook reforms in the 1960s, while China launched its reform and opening-up in 1978. In light of the lessons learned—concerning planning, markets, ownership of means of production and liberation of productive forces, and the interaction of relations and forces of production during socialist construction—it is possible to provide a systematic comparison. After providing background to the reforms, the comparison has four steps: 1) de-linking a market economy from a capitalist system, and the concomitant de-linking of a planned economy from a socialist system; 2) whether a market economy is a neutral instrument usable in any system, or whether it is a component shaped by the system of which it is a part; 3) planning and markets within a socialist system; 4) the relationship between ownership of the means of production (and control over the forces of production) and liberation of productive forces in the process of socialist construction. The fourth topic leads to the more foundational question of the dialectical interactions between relations and forces of production, since on this matter the economic definition of socialism turns.

Key words: Eastern Europe; China; economic reforms; comparison

In light of the renewed interest in the nature of market reforms within socialist systems, I offer a systematic comparative analysis of Eastern European and Chinese experiences. Some CMEA countries—especially Yugoslavia and Hungary—undertook such reforms in the 1960s, while China launched its reform and opening-up in 1978. That they had very different results is well known, with Eastern Europe (apart from Belarus) devolving into capitalist “shock therapy” while China took its reforms to a point where we are now entering yet a new stage in socialist construction, based on the prosperity that has been achieved. Along the way, many lessons have been learned, concerning planning, markets, ownership and liberation of productive forces, and indeed how the relations and forces of production interact with one another during socialist construction. It is precisely in light of these experiences that a systematic comparison becomes possible. The comparison that follows has four main steps: 1) the well-established de-linking of a market economy from a capitalist system, and the concomitant de-linking of a planned economy from a socialist system; 2) the question as to whether a market economy is a neutral instrument that can be used in any system, or whether it is a component that is shaped by the system of which it is a part; 3) planning and markets within a socialist system; 4) the relationship between ownership of the means (and forces) of production and liberation of productive forces, and thus the interactions between relations and forces of production. While the first three items concern the specific question of markets and planning within a socialist system, the fourth topic opens up the comparison to the more foundational question of the relations and forces of production. Foundational, since on this matter the very definition of socialism turns, specifically in terms of economic matters. While the topic itself concerns economic reform in a socialist context, my underlying concern is philosophical, seeking to determine the theoretical underpinnings of the similarities and differences between Eastern Europe and China.

Background to Economic Reforms

For readers not familiar with the historical background, I offer a brief summary.[1] Many of the countries in the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA)[2] began experimenting with market reforms in the 1960s. Initially, the new communist governments had seized control of production from the former ruling class and instituted old-style centralised planning. However, by the 1960s the early breakaway economic growth began to falter, and new contradictions emerged. A range of reforms began, with all of them entailing elements of market relations (Wagener 1998a, 8–9). Some went cautiously, maintaining a predominance of centralised management, such as the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Romania, and—after an initial burst of more far-reaching reforms—Czechoslovakia.[3] The DDR (East Germany) also had a period of reform in the 1960s, drawing lessons from the practice so as to enhance its centralised planning in the 1970s (Melzer 1982; Kraus 1998). The most significant market reforms took place in two countries, Yugoslavia and Hungary. The specific steps and mechanisms may have differed due to local conditions, but they shared an overall framework in terms of the scope of reforms, institutional adjustments, planning, and market incentives.

Yugoslavia made its initial moves early (due to expulsion from the Cominform in 1948) and eventually developed a decentralised system of self-managed worker enterprises in a “labour-managed market economy.”[4] They felt their way forward, since the path had never before been followed. By the 1960s, Yugoslavia had ended central planning, permitted worker-managed enterprises to determine what would be paid as salaries and what would be retained, transferred money from “social investment funds” to the banks, and sought integration with the global economy. Decentralisation was the watchword, moving ever outward to the republics, banking sector, and basic organisations of associated labour (BOALs). While Yugoslav economists spoke of moving from political to economic determination of the economy, from the state owning the means of production to workers doing so, questions remain as to how far they actually went.

In Hungary, the major step was the New Economic Mechanism (NEM) of 1968, which took on the dialectical challenge of improving planning by stepping back from direct planning.[5] The approach was described as “indirect centralisation,” preferring indirect economic levers. In place of centrally determined input and output, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were to compete, establish supply chains, set prices in light of material needs and production, be sensitive to consumer demands, and be driven to innovate. The result was a growth of worker cooperatives and a substantial non-state sector of the economy. While Hungary sought a fine balance between planning and a market, it experienced significant swings back and forth between what they saw as the centralising tendency of planning and the decentralising pull of markets (Szamuely and Csaba 1998).

China stuck to a centrally planned economy longer than the countries of Eastern Europe (although not the Soviet Union), but it has also taken the process of reform much further. For the first thirty years, accelerated socialised ownership of the means of production and a planned economy were the notable features. This was necessary at the time, not merely in terms of overcoming the devastating effects of semi-colonialism, feudal relics, and comprador capitalism, but also to get the economy moving from decades of revolutionary struggle and war. The results were stunning for a time, outstripping any other developing country (Cheng and Cao 2009; Cheng 2020, 99–101), but they eventually faced mounting contradictions leading to the launch of the reform and opening-up in 1978. At first tentative, drawing on farmer experiments in household responsibility and on market economic mechanisms in light of the overall planned economy, soon enough the reforms gathered speed. The four modernisations took off, the drive to prosperity became a major focus, and a socialist market economy became a foundational feature of logistics and distribution, albeit always coupled with a planned economy. It is constantly emphasised that all these developments have been undertaken for the purpose of socialist construction in light of the Four Cardinal Principles, so as to avoid rightist (bourgeois liberalisation) and leftist (an over-hasty leap to communism) deviations. We are now at a recognised point that China is moving into yet another stage, but I will say more in the comparative material to follow.

De-linking

In light of this background summary, I move to comparing the experiences in Eastern Europe and China. To begin with, both Eastern European and Chinese approaches assume the necessity of de-linking: a “market economy” is not by definition a capitalist market economy; and socialism is not exclusively defined by a planned economy. This de-linking is by no means new, but a few too many are still influenced by the deceptive slogan of one of the godfathers of a now defunct neoliberalism, Count Ludwig von Mises (1932, 142): “the alternative is still either Socialism or a market economy.” Why deceptive? Mises slipped in the assumption that socialism means a planned economy and that a market economy means a capitalist market economy. It is perhaps better if Marxist analysts do not hold to such a neoliberal assumption.

By contrast, the de-linking move has a long history, from Marx’s observations concerning the ancient Roman slave market economy, through ancient military market economies and feudal markets, before we even arrive at the possibility of markets within a socialist system (Marx [1894] 1983, 583–599; Boer 2015; Kula 1976). Thus, market economies have existed throughout human history, but only one form has become a capitalist market economy. As for the theoretical possibility of a market economic form within socialism, this emerged in an explicitly Marxist framework in the proposals of the Polish economist, Oskar Lange, and became a given position in Eastern Europe (Lange 1936, 1937; Bajt 1989; Horvat 1989).[6] By the 1970s in China, we find that Deng Xiaoping and his circle began to reaffirm this insight from Eastern Europe, now developed in light of Chinese conditions (Deng [1979] 2008, 236; see also Yang 2009, 174; Yang 2010, 11–13).[7] Clearly, we are on common and uncontroversial ground on the question of de-linking, although some of those who are unfortunate enough to have been brought up in a Western liberal context still need to be reminded of this common position.

Mechanism or Institutional Form

Given that a market economy is by no means coterminous with capitalism and can be deployed within other systems (including socialist ones), the next point of comparison concerns how one is to define a market economy. The dominant position in Eastern Europe was that a market is an “economic mechanism” (Szamuely 1982, 1984). In other words, a market was seen as a neutral economic instrument or tool that could be used within different systems. For example, Kornai (1959) argued in an earlier work that a market economic mechanism could be deployed in a socialist system through direct and indirect levers. The direct levers should be centralised through the state: direction of production, allocation of production materials, regulation of foreign trade, and managerial appointments. For Kornai, the problem thus far had been over-centralisation and the dominance of direct levers. Thus, he proposed a greater role for a number of indirect levers, specifically investment, the monetary system, the price system, and the wage fund.

Some of the earlier Chinese material—especially from the 1980s—used similar terminology: we find “method [方法fangfa],” “means [手段shouduan],” and “mechanism [机制jizhi]” (Deng [1990] 2008, 363–364; [1991] 2008, 367; Zhao 1987). Here too was a tendency to see a market as a neutral instrument, which could be deployed to “serve [服务fuwu]” the community and the common good. However, by the early 1990s specific terminology began to be used, distinguishing between an overall socialist system (制度 zhidu) and the specific institutional forms or structures (体制 tizhi and at times 体系 tixi)[8] within such a system (Deng [1992] 2008, 370; Jiang [1992] 2006; Huang 1994). In economic matters, there are two main institutional forms: a market economy and a planned economy. The institutional form of a market economy organises the forces and relations of production in a particular way, allocating resources and distributing products by means of the law of value, price signals, and competition. A planned economy organises the forces and relations of production by means of regulation, long-term calculation of means and ends, dealing with challenges, and setting perimeters for what can and cannot be done. The key point is that these two institutional forms are not necessarily antagonistic, for they may also work together within an overall system.

The specific terminology and the conclusions reached were the result of considerable debate in the late 1980s and into the 1990s. But why make this crucial distinction? It takes an important step beyond the instrumentalist position, in which a market is simply a neutral tool that can be used in different social systems. Instead, the institutional forms of market and planned economies are shaped, are determined in their nature, by the system in question.[9] Thus, if one has a foundational or “basic socialist system [社会主义基本制度shehuizhuyi jiben zhidu]” (Peng 1994, 13), then the institutional form of a market economy becomes not “market socialism” (which assumes an instrumentalist position), but a “socialist market economy.”[10]

We may also use the terminology of universal and particular: a market is a universal or commonality that may be deployed in the particularity of different systems, whether ancient Rome, feudal Europe, Western capitalism, or socialism. As Peng Lixun points out, the difference between a socialist market economy and a capitalist market economy is “not the generality [一般性yibanxing] of the market economy, but the particularity [特殊性teshuxing] of combining it with the basic socialist system” (Peng 1994, 13; see also Huang 1994, 4). Thus, to confuse an overall system with an institutional form is a profound category mistake. One final step: lest one still entertains the illusion that a market economy is an independent entity (“the market” as the neoclassical ideologues would have it), Huang Nansen (1994, 5) observes: “There is no market economy institutional form that is independent of the basic economic system of society.” One cannot have the institutional form of the market economy separate from the system of which it forms a part.

Planning and Markets

The third point of comparison concerns how the relations between market and planning were and are understood in Eastern Europe and China.

Eastern Europe: The Limit of Hard Budget Constraints

In Eastern Europe, they could not really get past the either-or opposition between planning and markets. The opposition took a number of forms, such as centralisation and decentralisation, state control and worker (economic) democracy, or vertical and horizontal relations. Much turned on whether one valued market relations or the state’s role. For some, the state was a hindrance, blocking the full development of a market “proper”;[11] for the majority, however, the state was seen as a distinct positive, especially since a strong and efficient state was the initial means for transforming the economy, society, education, and culture in a socialist direction (Brus 1973, 1975, 65; Brus and Laski 1989; Kozma 1982, 94). The ideal became “central planning with a regulated market” (Brus 1973, 1–20), with market relations functioning in many areas while the state oversaw the whole process and ensured equity, since the interest of society could not be reduced to the sum-total of individual interests. These remained ideals, for too often planning and markets were seen in opposition to one another. Thus, there were starts and stops, two steps forward and then a step back, as well as the differences between Hungary and Yugoslavia (which went much further) and other CMEA countries that retreated to central planning after tentative experiments.

How far did they go? How many market mechanisms could one use? As many Eastern European economists argued, market socialism includes market choices by individuals and enterprises, supply-and-demand price mechanisms, “profit” as a necessary bottom line for an enterprise’s viability, division of labour, and wage differentials. However, they stopped short in three crucial areas: hard budget constraints (entry and exit) for enterprises; pricing determined fully by market dynamics; and the law of value. Let me use the example of budget constraints in Yugoslavia, which had one of the most developed forms of market socialism. Despite the complexity of “soft” budget constraints, with the need for perpetual bargaining and elements of “hard” constraint where the state enforced reforms to ensure economic viability, the Yugoslav government was ultimately not willing to allow enterprises to “exit” if they failed to be financially viable (Kornai 1986, 1992, 487–496; Nove 1991). Thus, the state continued to “underwrite” enterprises so that none of them would suffer bankruptcy. As for prices, these were always regulated in some way, and they were never really able to tackle the law of value.

China: Reshaping the Law of Value

The contrast with China is notable. Here they have “gone all the way,” as it were, implementing all of the crucial common features of a market institutional form. This includes market pricing for most goods, hard budget constraints and thus “entry” and “exit” for many enterprises (including inefficient SOEs in the 1990s), and the law of value. Of course, the key SOEs, which remain the main economic drivers in China, are subject to “soft” budget constraints. But—staying with the metaphor—there is a distinctly hard edge to such constraints: the SOEs have been undergoing constant reform, learning from market efficiencies, ensuring the budget bottom line, and emerging as hubs for innovation and expansion.

Let me say a little more concerning the law of value, which is seen as a basic principle (基本原则jiben yuanze) of Marxist political economy. This is not an ossified basic principle, unchangeable for all time, since even the basic principles need constant deepening and development in light of the theoretical implications of specific solutions for particular problems (Cheng 2020, 102). In terms of the Marxist law of value, the distinction between use value and exchange value, and the identification of surplus value produced by workers as the key to capitalist exploitation, arose through the analysis of a capitalist system. But does the labour theory of value also apply to socialist construction and a socialist system? If so, how? One may find plenty of statements to the effect that one must have a law of value if one has a market institutional form (Yang 1994, 6; Zhang and Zhuang 1994, 5; Gao and Zheng 1996, 4; Huo 2011).[12] But how does it work in the qualitatively different context of a socialist system?

On this matter, Cheng Enfu and his colleagues have been among the foremost proponents for reworking this basic principle, which they see as an inescapable part of a market institutional form (Cheng, Wang, and Zhu 2005, 2019; Cheng 2007, 16–21). Cheng defines Marx’s theory as follows:

all labour that directly produces material and immaterial goods for market exchange, as well as labour that directly serves the production and reproduction of labour goods, including the internal management labour of natural and legal entities and scientific and technological labour, are value-creating labour or productive labour. (Cheng 2007, 16)

Already we can see the effort to develop the theory beyond Marx’s focus on: a) production of material goods in industry, agriculture, construction, and so on; b) transport or circulation of goods. Cheng and his colleagues go much further, arguing that value is also produced in: c) “intangible spiritual [无形精神wuxing jingshen]” goods, by which is meant activities that contribute to cultural vitality, such as education, research, art and literature, media, and so on; d) “service labour [服务劳动fuwu laodong]” involved in activities such as medical care, health, and sports; e) management and direction of enterprises, in the sense that such labour involves the management of socialised labour, along with the surplus value that arises from private ownership; f) changes in the objective and subjective conditions of labour (leading to complex outcomes depending on where changes are located), with the main trajectory of such changes being the increase in the complexity, proficiency, and intensity of labour so as to improve the total value of goods and the total social value. This brief summary indicates sufficiently well the effort at reworking the labour theory of value, although Cheng also adds wealth and distribution, in terms of the “total factors involved in wealth production” (land, resources, finance, ecology) and “distribution according to work [按劳分配anlaofenpei]” (along with other forms of distribution).[13] Together, these three—living labour, wealth, and distribution—form a whole, with labour at the core.

What is the outcome of this proposal concerning the “creation of value by living human labour [活劳动创造价值huolaodong chuangzao jiazhi]”? First, the theory of value applies not merely to the industrial worker (工人gongren) but to all forms of labour (劳动laodong)—of which there are hundreds recognised in China. Second, this proposal clearly emphasises the social production of value: it takes place not merely through the selfish individual producer seeking self-aggrandisement (as assumed by neoclassical economics [Cheng 2007, 21–24]), but is a social reality. Third, it follows that the theory of value applies not merely to the socialist market economy, but to the whole of socialist society. On this matter, there is some difference of opinion among Chinese scholars, with some arguing that the law of value applies only to the market institutional form, while others argue that it should be extended to embrace social or public value. I suggest that Cheng Enfu’s proposals also move in the latter direction, especially when he speaks of the increase in “total social value [社会价值总量shehui jiazhi zongliang].” Or, as he proposes elsewhere, the “Gross Domestic Welfare Product [国内生产福利总值guonei shengchan fuli zongzhi],” or GDWP, which draws together the areas of economy, nature, and society in order to determine a comprehensive “final gross welfare product [最终福利总值zuizhong fuli zongzhi]” (Cheng and Cao 2009; Cheng 2020, 101).

Planning, Market, and Non-antagonistic Contradictions

To return to the question of relations between planning and market, we find in Chinese scholarship a range of formulations, although they are not mutually exclusive: fairness of planning and efficiency of a market; benefits for all and innovation; public economy and private economy; regulation according to proportion and regulation according to value; and so on. Through such formulations, the emphasis is on seeking ways for the two institutional forms to enhance one another, with planning focused on improving conditions for market mechanisms and ensuring that they work for the public good, and markets providing insight into improved efficiency and functionality for planning. But let me step back for a moment and put this in more philosophical terms: in the context of contradiction analysis, the category of non-antagonistic contradictions is the key. Stemming from Lenin and thoroughly reworked in a Chinese context, it is very clear that during socialist construction contradictions continue to appear.[14] But such contradictions are now by default non-antagonistic. To be sure, they need to be managed so as to maintain such a non-antagonistic nature (Mao [1957] 1977), but this is to ensure the norm rather than trying to soften the hard edges such as in—for example—a rampant capitalist system. So also with the institutional forms of planning and market. It is in this light that we should understand the moves to speak of a dialectical transcendence (超越chaoyue) or sublation (扬弃yangqi, a translation of the German Aufhebung) of the old opposition of planned and market economies in what more and more are beginning to see as a distinct new stage of China’s development (Zhang 2009, 139; Fang 2014, 63; Zhou and Wang 2019, 41).

Ownership and Liberation of Productive Forces

The question of planning and market leads to the wider question of the relationship between ownership of the means (and forces) of production and liberation of productive forces, which is a specific manifestation of the foundational dialectic of relations and forces of production. But let us step back for a few moments: since this topic is a basic principle of Marxist analysis and takes us to the heart of the economic definition of socialism, I begin with some exegesis of texts by Marx and Engels. These texts will enable me to establish a framework for identifying the historical emphases and shifts in Eastern Europe and then China.

Marx and Engels

In the “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” Marx and Engels look forward to the exercise of power by a communist party after a successful proletarian revolution for the sake of socialist construction:

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production [Produktionsinstrumente] in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total of productive forces [Produktionskräfte] as rapidly as possible. (Marx and Engels [1848] 1974, 481)

There are two main parts in this sentence. The first concerns the gradual—“by degrees”—seizure of capital and the centralisation of all the instruments or means of production in the hands of a proletariat that now controls the reigns of power. In short, this is the centralised ownership of the means of production by the proletariat embodied—at this point—in the state. The second part concerns the accelerated increase of productive forces, or what we may call, following standard Chinese practice, the liberation of productive forces (解放生产力jiefang shengchanli).[15] Clearly, for Marx and Engels both ownership of the means of production and liberation of productive forces are needed for the process of socialist construction.

Let us stay with ownership for a moment: does such ownership pertain only to the instruments or means of production? Here Engels’s overview in “Karl Marx” is revealing:

The productive forces of society [gesellschaftlichen Produktivkräfte], which have outgrown the control of the bourgeoisie, are only waiting for the taking possession [Besitzergreifung] of them by the associated proletariat in order to bring about a state of things in which every member of society will be enabled to participate not only in production but also in the distribution and administration of social wealth, and which so increases [steigert] the productive forces of society [gesellschaftlichen Produktivkräfte] and their yield by planned operation of the whole of production that the satisfaction of all reasonable needs will be assured to everyone in an ever-increasing measure. (Engels [1877] 1985, 109; see also [1847] 1972, 377; [1894] 1973, 263–264)

Notably, Engels takes a step further than the “Manifesto,” speaking here of “productive forces” (Produktivkräfte 生产力) in regard to both ownership and liberation. Thus, the productive forces require a seizure, a taking possession (Besitzergreifung) by the proletariat, with the outcome that the productive forces will increase (steigert). In this case, the taking possession or ownership also leads to a planned economy, as the flow of Engels’s text indicates. For Engels, ownership—entailing a range of meanings that includes seizure, possession, and control—applies to both the means of production and the forces of production. It is in this sense that I will use the terminology of “ownership” below.[16] However, some questions remain. Are these relatively brief programmatic statements relevant only after the initial seizure of power through a proletarian revolution? Is there a causal relationship between one or the other term?[17] How will the dialectic of liberation and ownership unfold over the long process of socialist construction? Marx and Engels were very careful to note that they had no experience of the construction of socialism, with a communist party in power, so they stressed that the actual results could be determined only from experience and “only scientifically [nur wissenschaftlich]” (Marx [1875] 1985, 22), and that to “attempt to answer such a question in advance and for all cases would be utopia-making” (Engels [1873] 1984, 77).

One further question: what is the starting point of ownership (of both means and forces of production)? Given that this ownership is by the proletariat as a class, the perspective is that of the relations of production. By contrast, liberating the productive forces begins from the perspective of such forces, which include human labour and means of production.[18] It follows that the questions of ownership and liberation are specific manifestations of the core dialectical interaction between relations and forces of production.[19] Let me emphasise that this is a dialectical relation, requiring both features in a constantly unfolding process: the one needs the other, with constant readjustments as one side leaps ahead and the other side needs to be brought up to speed (Stalin [1952] 1997, 196–205).[20]

The First Stage: An Emphasis on Ownership

I have devoted some attention to the material from Marx and Engels and its implications, since it provides the necessary framework for understanding how economic emphases have unfolded in the historical process of socialist construction. We may distinguish initially between two periods, which for now can be designated in terms of an emphasis on ownership of the productive forces, and then by a shift in favour of their liberation—albeit always in a dialectical relation to one another.

To begin with, in both Eastern Europe and China there was a common assumption that the emphasis immediately after a revolutionary seizure of power should be radical changes in the relations of production, manifested specifically in terms of the seizure, ownership and thus control of the means and indeed forces of production. The logic behind this move was straightforward: drawing from Marx and Engels, they identified the main contradiction of a capitalist system in terms of socialised labour and the private ownership of the means and forces of production by the bourgeoisie and remnants of the landlord class. It followed that a communist party in power should seek to transcend the contradiction by socialising such ownership (Engels [1894] 1973, 260). Other factors made this a necessary move, particularly the need to prevent counter-revolution and instigate the economic structures needed both to overcome the previous system and begin the process of socialist construction—abolition of bourgeois private property, industrialisation in light of “backward” economic conditions, collectivisation of agriculture, and a fully planned economy.

Not unexpectedly, this initial move led to an intense focus on production relations, predicated on the belief that the elimination of private ownership would produce equality and social justice. In Eastern Europe, it was very soon assumed that production relations constituted the main subject of Marxist political economy and thus policy-making. In some cases, this focus moved in a volitional direction, assuming that human beings could create, amend, and abolish economic laws themselves (Kraus 1998, 286).[21] In China and in light of its cultural tradition, we do not find such extreme expressions. Already from the time of Mao’s lectures on dialectical materialism (Mao [1937] 1984), the dialectical interaction of the forces and relations of production was a crucial analytic approach. Thus, while Mao did seek to overcome the contradiction inherent in capitalism (Mao [1937] 2009, 318) through the socialisation of ownership, he saw this as a means to liberate production forces (Mao [1945] 2009, 1079; [1956] 2009).

This is precisely what happened in the initial period. There is abundant evidence to show that in both Eastern Europe and China economic production leapt ahead. For example, the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany became highly industrialised economies, and the other countries of the CMEA saw significant growth (Höhmann 1982, 1–2; Kozma 1982, 99–104). In China, the “first economic miracle” included significant developments in science and technology, an independent industrial and national economic system, development of education, culture and health, population growth (in numbers and life expectancy), great improvement in socio-economic well-being, and China’s emergence in international affairs, all the way from the United Nations to increased appeal in and engagement with developing countries (Cheng and Cao 2009, 6–8).

The Second Stage: New Means of Liberating Productive Forces

Nonetheless, internal contradictions began to mount. In Eastern Europe, the almost exclusive public ownership (through the state) and the fully-planned economy was showing signs of a limit-point, with supply-side structural blockages, rapid and uneven development over a relatively short period, constant tensions between expanding or modernising production, the risk of overspending national incomes for the sake of production so as to meet consumption demands, and the decline in creative solutions. In short, economies began to stagnate, leading to increased tensions in the relations of production that threatened to become antagonistic (Kozma 1982, 172–176; Kraus 1998, 315–316). In China too problems started to become apparent. Even with all of the achievements noted above, there had been signals of mounting contradictions including the persistence of poverty in rural areas and many regional cities, the emphasis on class struggle in the 1960s, and the increased focus on liberating productive forces through sheer volitional effort (Lin 1969, 8).[22] By the 1970s, intractable contradictions in China’s economic development had become all too apparent (Deng [1982] 2008, 16; Wang and Yang 1994, 105).

The response in both Eastern Europe and China was to seek alternative ways to liberate productive forces, and the approach was to develop in various ways a market institutional form within a socialist system. As already noted, the Eastern European efforts were tentative: they were feeling their way forward along a new path and never managed to resolve many of the new questions in the time they had remaining. China managed to avoid the snares that caught Eastern European countries, in part through careful studies of what went wrong in Eastern Europe, and in part through “pilot projects” that carefully tested new measures before they were implemented country-wide. Thus, while the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe succumbed to the contradictions and suffered the devastating effects of capitalist-imposed “shock-therapy,” China launched itself on a path that has led to its status today as a global economic power. While nominally the “second largest economy” in terms of GDP, on other measures it contributes more than any other country to the global economy (more than 30%), its industrial output and foreign exchange reserves are the highest in the world, it has the largest internal market, it has developed a comprehensive system of quality education, health, and welfare, and it has seen Hong Kong and Macao return (Cheng and Cao 2009; see also Cheng 2018, 2–3; Cheng 2020, 99–101).[23]

Let us pause for a moment and assess the shift to the second stage of economic development. In terms of the dialectic of forces and relations of production, the initial period entailed radical transformations in the relations of production, focused on ownership of the means of production and control over productive forces, so as to spur economic development. Over time, the relations of production became a drag on productive forces, since the latter had leapt ahead and the former had not kept pace. Hence the reforms in Eastern Europe of the 1960s and the reform and opening-up in China from 1978. However, this was not necessarily the way such developments were perceived on the ground. As noted earlier, in Eastern Europe there was a tendency to focus on the tensions between planning and market, with questions turning on the nature of ownership. By contrast, it can be argued that in China the key was liberating productive forces: the question concerned the best means to enable such liberation. Was it to be accelerated ownership of the productive forces, which was the emphasis of the first stage? Or was it to be a socialist market economy in conjunction with planning, as in the second stage?

In order to understand this emphasis, let us turn to another country with the same initial problem as China: Vietnam. Here too was a poverty-stricken country seeking a socialist path of development, but Vietnam was able to enter into this path somewhat later and thus benefited from the experiences and insights of others. Here the emphasis on productive forces never really slipped into the background. For example, a consistent theme of Le Duan’s speeches from the 1960s—before the success of the revolutionary struggle that united north and south—is that the new production relations require an adequate content through the advancement of productive forces. More concretely, this means building “a material and technical basis for socialism” that is embodied in “large-scale industry capable of providing all branches of the national economy” with the necessary technical equipment. The reason: “only on this basis can we carry out a rational new division of labour in our society, a rational utilisation of our country’s labour power and resources, and attain a high labour productivity” (Le 1963, 180; emphasis added; see also Le 1960, 22–23). In Vietnam, this dialectical coordination of the forces and relations of production was seen as the only way to satisfy the people’s material and cultural needs. Clearly, the lessons from China, and indeed from Eastern Europe, had pressed upon Vietnam the need for economic development, of emphasising the inescapable importance of productive forces and their liberation, so as to provide content for the relations of production.

This was, of course, the signature emphasis of Deng Xiaoping. While he acknowledged the fact that Mao Zedong too had wanted to develop productive forces, Deng pointed out that “not all of the methods Mao used were correct” (Deng [1985] 2008b, 116). For Deng the “development of the productive forces . . . is the most fundamental [最根本zui genben] revolution from the viewpoint of historical development” (Deng [1980] 2008, 311). “Poor socialism” is not socialism; instead, socialism should seek to develop productive forces, improve the country’s strength and the lives of the people (Deng [1986] 2008, 172; [1992] 2008, 372).

A New Stage: Dialectical Sublation (扬弃yangqi)

Thus far, I have outlined two main stages in the path of socialist construction. With varying emphases and time-frames, we can see these stages in both Eastern Europe and China. That the second stage, involving a market institutional form, went in diametrically opposed directions in each place is well-known—albeit not for want of hoping for a fully functional “market socialism” in Eastern Europe (Balcerowicz 1989; Bajt 1989; Brus 1989, 1992; Dyba 1989; Horvat 1989).[24] At this point, Eastern Europe drops out of our analysis, but it needs to be asked: why did Eastern Europe—with the notable exception of Belarus[25]—devolve into “shock therapy” capitalism? Many are the potential answers, but in terms of the analytic framework used here, I propose two reasons. First, they did not embrace the dialectical need to develop a full market institutional form for the sake of the socialist road. Instead, it was precisely the half measures, the swerving this way and that, that set up a capitalist turn. Second, they lacked the strong state structures—a crucial feature of socialist systems since the Soviet Union in the 1930s—to enable such a dialectic.[26] On both counts, China has succeeded.

As a result, in China it is becoming apparent that a new and third stage is now well underway. This stage is usually dated from 2012, the beginning of Xi Jinping’s tenure as General Secretary of the CPC and President of the People’s Republic of China. Before considering the many indicators of such a stage, let me step back a moment and focus on the new contradictions that arose as a result of the resolute emphasis on liberating productive forces during the decades of the reform and opening-up. In the midst of China’s stunning economic success, a spate of well-documented and widely-studied problems became apparent during the “wild 90s,” and even into the early 2000s: declining conditions for workers and consequent unrest; illegal appropriation of collectively owned village lands; a growing gap between rich and poor regions; environmental degradation; ideological disarray, with proposals ranging from the recovery of Confucianism to bourgeois liberalisation; and a rift between the CPC and the common people, leading to corruption and lack of knowledge of Marxism even by leading cadres. In light of these new contradictions, two core questions arose. First, were they systemic to the reform and opening-up, as a few too many Western observers assumed, or were they contingent and incidental to the overall process? The answer comes straight of Marxist dialectical analysis: they were incidental to the larger process of socialist reform (Lo 2007, 120–121, 129). Second, what was to be the solution? Here the answer too is dialectical, deploying contradiction analysis: the way to solve these internally generated contradictions was to deepen the reform process itself (CPC Central Committee 2013; Xi 2018; Zan 2015).

One way to consider the results in China is in terms of public ownership. In light of repeated warnings from scholars and policy advisers such as Cheng Enfu concerning a drift away from public ownership as the mainstay (Cheng 2007; Cheng and Xie 2015, 59–60), there has been a notable tightening up on private companies,[27] and a strengthening and reform of state-owned enterprises so that, as efficient hubs of innovation, their role as the backbone of the economy is being enhanced (Xi 2017). But this is only one perspective, and it risks seeing the shift in emphasis as a type of return to the features of the first stage.[28] Instead, the process of deepening reform is far more comprehensive (全面quanmian), covering a full range from the economic base to superstructural components. We can already begin to see clear results: about 800 million rural and urban workers have been lifted out of poverty, with almost 500 million now in a “middle-income” group (and not a “middle class”[29]); the gap between rich and poor has been decreasing now for about a decade; rural and urban workers are engaged in all aspects of China’s ever-strengthening socialist democratic system; in light of ecological civilisation, China has become a world leader in “green growth”; and the almost 100-million strong CPC is more united, more knowledgeable about Marxism, and more focused on the task ahead than at almost any time in its past. The formulations of the new stage vary, such as China “has stood up, become better off, and grown in strength [从站起来、富起来到强起来]” (Xi 2020b, 12) and the “third economic miracle [第三个经济奇迹di san ge jingji qiji]” (Cheng and Cao 2009, 6) or “socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era [新时代中国特色社会主义]” (Xi 2020b, 1).

Conclusion

In this comparison between Eastern Europe and China, I began with the specific question of market and planning institutional forms within a socialist system. On this matter, I found common ground on the question of de-linking, and in terms of the underlying dynamics that led to reforms in Eastern Europe in the 1960s and China from 1978. Differences also emerged: in seeing a market as a neutral “economic mechanism” or as an institutional form that is shaped by and indeed inseparable from the system of which it is a part; in a tendency to see planning and market in an either-or tension and thus seeking a delicate balance, or to seeing them in a both-and relation, with the one enhancing the other in terms of non-antagonistic contradictions.

The treatment of planning and market led me to address the more foundational question of ownership (of both means and forces of production) and liberation of productive forces, and thus the dialectic of relations and forces of production. There is no need to repeat the detail of that discussion here, so let me conclude with a more philosophical observation concerning the approach to contradictions. Eastern Europe reveals some influences from the Western philosophical tradition’s emphasis on either-or, or zero-sum.[30] Thus, we found a heavy focus on ownership—at least in the initial stage—and a tendency to see this emphasis in tension with liberating productive forces through a market mechanism. As noted earlier, this either-or approach was manifested in a series of related oppositions: centralisation and decentralisation, state control and economic democracy, or vertical and horizontal. By contrast, in countries such as China and Vietnam the emphasis has arguably been on finding the best way to liberate productive forces. Undeveloped economic conditions, as well experiences of European imperialism, play a significant role in this emphasis, but there is also a cultural and philosophical emphasis on both-and, in the sense that “what is contradictory is also complementary [相反相成xiangfan-xiangcheng].” In Marxist terminology, we may speak of non-antagonistic contradictions in socialist construction. So the key question was: how to enable such liberation? Through radical transformation of the relations of production, characteristic of the first thirty years? A resolute emphasis on productive forces, as we find with the reform and opening-up? Or a people-centred approach, as a dialectical transformation of the first two stages? Historically, the answer is obviously affirmative for all three questions. That there will be new contradictions—such as the policy of “dual circulation [双循环shuang xunhuan]”—goes without saying.

[1] For more detail, see a couple of earlier works (Boer 2021a; 2021b, 115–138).

[2] The CMEA included all Eastern European countries, along with Mongolia, Cuba, Vietnam, and Yugoslavia as an equal trading partner in 1964.

[3] Country by country economic surveys may be found in Nove, Höhmann, and Seidenstecher (1982) and Wagener (1998b).

[4] On Yugoslavia there is a wealth of rarely-studied material available (Vanek 1972; Dubey 1975; Rusinow 1977; Estrin 1983; Lydall 1984; Brus and Laski 1989, 87–101; Nove 1991, 175–184; Gligorov 1998; Mencinger 2000).

[5] Again, there are many studies of the Hungarian experience (Brus and Laski 1989, 61–72; Nove 1991, 162–175; Swain 1992; Szamuely and Csaba 1998; Bockman 2011, 105–132).

[6] Lange’s approach was that of Marxist political economy, but he was heir to a longer non-Marxist theoretical tradition that examined the possibilities of markets and competition in a “socialist state.” Thus, Walras suggested that only such a state would provide the necessary institutions for market competition and just distribution, and Pareto and Barone argued for a “Ministry of Production” that would ensure competitive markets, determine equilibrium prices, and so maximise socio-economic well-being, including redistribution where needed. For Barone, this may be conceivable theoretically, but was—he opined—practically impossible. In part, Lange’s studies sought to show that it was very much possible (Walras [1896] 2014; Pareto 1896, 56–59; 1902; Barone [1908] 1935).

[7] In a Chinese context, the issue was raised in an initially ignored study by Yu Zuyao (1979), only to be picked up by Deng Xiaoping and others within a few months.

[8] If one consults a Chinese dictionary, one will find 体制tizhi translated as structure, organisation, and set-up. But since the terminology became very specific, I translate the word as “institutional form,” a term drawn from Régulation Theory (Boyer and Saillard 2002). An “institutional form” is a specific building block or component of a larger system, and it is one among others.

[9] Of all the Eastern European sources I have studied, only Horvat (1989, 233) makes this point: “It is not the market that determines a social system; it is, on the contrary, the socio-economic system that determines the type of the market.”

[10] As Xi Jinping observes,

The term “socialist” is the key descriptor, and this is something that we must never lose sight of. We call our economy a socialist market economy because we are committed to maintaining the strengths of our system while effectively avoiding the deficiencies of a capitalist market economy. (Xi 2020a)

[11] This position is particularly noticeable in Janos Kornai, who began as a proponent of a market mechanism within a socialist system and ended up as an ideologue for a capitalist system (Kornai 1992, 1993; 2006, 273–275).

[12] The necessity of a law of value was already emphasised by Mao Zedong in the late 1950s, and came to the fore again in the 1980s with Deng Xiaoping (Mao [1959] 2009; Deng [1985] 2008a, 130; [1988] 2008, 262).

[13] 按劳分配anlaofenpei is a four-character rendering of the principle of socialism initially identified in the Soviet Union of the 1920s and 1930s: from each according to ability, to each according to work (Boer 2017, 30–36).

[14] As Lenin famously put it in his notes on Bukharin: “Antagonism and contradiction are not at all the same thing. Under socialism, the first will disappear, the second will remain” (Lenin 1920, 391). Drawing on Engels and Marx, Lenin ensured that the category of non-antagonistic contradictions would become a staple of Marxist dialectics until this day (Boer 2021b, 55–84).

[15] We already see this terminology emerging in the 1950s (Mao [1956] 2009), and it became a signature emphasis of Deng Xiaoping.

[16] It should be noted that the terminology was not fully clarified in the works of Marx and Engels (see especially Engels [1894] 1973, 263–264), and it would take later developments to achieve such clarity. Most of the terminology was developed and established in the Soviet Union, and one may usefully compare the three editions of the authoritative Great Soviet Encyclopedia to see how the terminology was clarified (Berestnei 1940; Malyshchev 1955; Vasilchuk 1975). Here we find that the productive forces are defined as the combination of human labour power with the means of production so as to transform the raw materials of nature in the creation of socio-economic well-being (and thereby determine the level of society). In this definition, the means of production are a subset of the forces of production, but the term has a specific meaning: the means of production constitute all of the materials necessary for human beings to engage in production. Or, as Marx suggests in the first volume of Capital (Marx [1867] 2004, 131), labour resources (劳动资料laodong ziliao) and the objects of labour (劳动对象laodong duixiang) together constitute the means of production.

[17] Engels in particular suggests that there is a causal relation, as the text quoted above indicates, as well as his fuller statement in Anti-Dühring (Engels [1894] 1973, 263–264).

[18] Here I follow standard usage (see note 16): while human labour is one of the productive forces, the specific relations of human beings to one another in the process of production, which is often manifested in terms of class relations, constitute the relations of production (生产关系shengchan guanxi).

[19] This is not to say that the framework of forces and relations of production is the only way to analyse developments. For sake of clarity and focus, I leave aside—or at least mention briefly—the question of volitional or ideological features at certain points, the role of the state not merely in planning but also in overseeing a market institutional form, and the relations between formal and real socialisation (see footnote 27).

[20] Stalin pointed out that certain economic laws have a valence in socialist construction—not least the contradictions between the forces and relations of production. On the one hand, the radical shift in relations of production—public ownership and collectivisation—had a profound effect on unleashing productive forces after the October Revolution; on the other hand, the dialectic of forces and relations of production changes in light of specific conditions. In a certain situation, the forces of production lag and become a fetter on production relations, while in another situation the reverse applies. The solution: the laggard needs to be brought up to speed. Notably, Stalin’s text produced a temporally shortening effect: while the Soviet Union had already experienced three decades of socialist construction, with the consequent experience of new problems in Eastern Europe Stalin’s text appeared early in the piece in relation to their economic development. It would take a decade or more for the practical implications to emerge in terms of the reform programs.

[21] This emphasis led to significant debate concerning the nature and range of ownership, which included: the nature of private property in a socialist system in which public ownership of the means of production was the norm; the various types of ownership that were emerging; and the distinction between public ownership (by the state on behalf of society) and social ownership, in the sense of society having effective disposition over the means of production it owns (Horvat 1969; Brus 1975; Brus and Laski 1989).

[22] In some respects, the emphasis on volitional solutions, characteristics of leftist emphases, may be seen as an over-compensation for the initial inability to overcome the problem of lagging productive forces. Many thanks to Antonis Balasopoulos for this insight.

[23] During this time, we also find a significant reassessments of the category of ownership. The oft-repeated principle is that public ownership should be the mainstay, while other forms of ownership can also exist in a “mixed ownership economy [混合所有制hunhe suoyouzhi].” In this context, there was an emphasis on the diverse forms that public ownership may take. Instead of a single form of public ownership, we find state-owned enterprises, cooperatives, collectively owned farm land, and the public dimensions of private enterprises with their CPC units and social responsibility reports. While a significant diversity of private ownership also arose, this was never seen in terms of neo-liberal privatisation (Thesis Group 2009, 94–95; Cheng and Xie 2015, 61).

[24] I have deliberately not included Gorbachev’s perestroika in the Soviet Union, since this was a distinctly non-socialist experiment.

[25] The case of Belarus requires another study. Belarus responded to the chaotic and economically destructive privatisation in the former Soviet Union with a deliberate shift to realising “market socialism” when Lukashenko came to power in 1994. For a careful study, see Li and Cheng (2020).

[26] On the Soviet Union and its breakdown, see further Cheng Enfu and Liu Zixu (2018, 70–71), who identify ideological confusion from the time of Khrushchev’s extreme negation of Stalin, the breakdown of organisational discipline that enabled non-communists to rise to leadership, and resultant disavowal of scientific socialism by such leaders. A major reform and renewal of the socialist path requires a united, disciplined, and theoretically knowledgeable communist party, and thus a well-functioning governmental apparatus to see the process through.

[27] This strengthening and tightening up of regulation may be seen more recently with regard to Ant Group and Evergrande.

[28] On this question, another level of analysis can also be deployed, now in terms of formal and real socialisation of production. While this approach would require a different study from the present one, it may be argued that the initial stage of socialist construction tended towards formal socialisation, with accelerated ownership of the means of production and control over the forces of production. By contrast, real socialisation can take place only with the liberation of productive forces, thereby providing substantive resources for socio-economic well-being. This liberation—as argued—began in the second stage, but is beginning to be realised in the third stage, with its emphasis on common prosperity for all. I would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for suggesting this perspective.

[29] This brief observation touches on a topic of significant debate in China that would require another paper to address adequately. My comment takes sides in a debate, indicating that “middle class [中产阶层zhongchan jieceng]” in English carries with it a semantic field associated with the growth of capitalism in Europe, especially traders and merchants in towns who came to form a “bourgeoisie” (the term originally meant town-dwellers) that eventually were the agents of bourgeois revolutions. It is due to these connotations with capitalist development that “middle class” in English is inappropriate for socialist construction. Thus, the more neutral “middle-income group [中等收入群体zhongdeng shouru qunti]” is the appropriate term. On this matter, I follow the trend of recent research (Cai 2018; W. Li 2018; 2021; Liu and Liu 2021).

[30] Given the either-or emphasis in the Western tradition, it is notable that Western definitions of socialism focus on the ownership of the means and forces of production and neglect the liberation of such forces. It should also be obvious that such an emphasis arises from contexts where—at least until recently—productive forces have been relatively highly developed.

References

Bajt, A. 1989. “Socialist Market Economy.” Acta Oeconomica 40 (3–4): 180–183.

Balcerowicz, L. 1989. “On the ‘Socialist Market Economy.’” Acta Oeconomica 40 (3–4): 184–189.

Barone, E. (1908) 1935. “The Ministry of Production in the Collectivist State.” In Collectivist Economic Planning: Critical Studies on the Possibilities of Socialism, edited by F. von Hayek, 245–290. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Berestnei, V. 1940. “Proizvoditelʹnye sily obshchestva i proizvodstvennye otnosheniia liudei” [The Productive Forces of Society and the Production Relations between People]. In Bolshaia sovietskaia entsiklopediia [The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia], vol. 47, 1st ed, edited by O. I. Schmidt, 145–162. Moscow: Gosudarstvennyi institut.

Bockman, J. 2011. Markets in the Name of Socialism: The Left-Wing Origins of Neoliberalism. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Boer, R. 2015. The Sacred Economy of Ancient Israel. Library of Ancient Israel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox.

Boer, R. 2017. Stalin: From Theology to the Philosophy of Socialism in Power. Beijing: Springer.

Boer, R. 2021a. “Socialism and the Market: Returning to the East European Debate.” New Political Economy Online: 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1926958.

Boer, R. 2021b. Socialism with Chinese Characteristics: A Guide for Foreigners. Singapore: Springer.

Boyer, R., and Y. Saillard, eds. 2002. Régulation Theory: The State of the Art. London: Routledge.

Brus, W. 1973. The Economics and Politics of Socialism: Collected Essays. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brus, W. 1975. Socialist Ownership and Political Systems. Translated by R. A. Clarke. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brus, W. 1989. “From Revisionism to Pragmatism: Sketches towards a Self-Portrait of a ‘Reform Economist.’” Acta Oeconomica 40 (3–4): 204–210.

Brus, W. 1992. “The Compatibility of Planning and Market Reconsidered.” In Market Socialism or the Restoration of Capitalism?, edited by A. Åslund, 7–16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brus, W., and K. Laski. 1989. From Marx to the Market: Socialism in Search of an Economic System. Oxford: Clarendon.

Cai, W. 2018. “Be Wary in Using Concepts Like ‘Middle Class’.” [In Chinese.] Leading Journal of Ideological and Theoretical Education no. 8: 93-98.

Cheng, E. 2007. “Four Theoretical Hypotheses for Contemporary Marxist Political Economy.” [In Chinese.] Social Sciences in China, no. 1: 16–29.

———. 2018. “The Significant Achievements of Marxism and the Theory of Sinification—On Xi Jinping’s Economic Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.” [In Chinese.] Southeast Academic Research 2018 (5): 1–8.

Cheng, E. 2020. “Ten Major Points of View of Marxism in the Context of an Academic Career.” [In Chinese.] Research on the Theories of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, no. 5: 97–107.

Cheng, E., and L. Cao. 2009. “How to Establish an Accounting System for the Gross Domestic Welfare Product.” [In Chinese.] Economic Review, no. 3: 1–8.

Cheng, E., and Z. Liu. 2018. “An Analysis of the Economic Development of the Soviet Union and the Reasons for Its Disintegration.” [In Chinese.] Journal of Theoretical and Political Education, no. 1: 67–71.

Cheng, E., G. Wang, and K. Zhu. 2005. A Normative and Empirical Study of the Value Created by Labour—A New Wholistic Theory of the Value of Living Labour. [In Chinese.] Shanghai: Shanghai University of Finance and Economics Press.

Cheng, E., G. Wang, and K. Zhu. 2019. The Creation of Value by Living Labour: A Normative and Empirical Study. Edited by A. Freeman. Translated by L. Hui and Y. Sun. 2 vols. Berlin: Canut.

Cheng, E., and C. Xie. 2015. “On the Mixed Ownership Systems of Capitalism and Socialism.” [In Chinese.] Studies on Marxism, no. 1: 51–61, 158–159.

CPC Central Committee. 2013. “Decisions by the CPC Central Committee concerning Several Major Issues on Comprehensively Deepening Reform.” [In Chinese.] People.cn, November 15. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1115/c1001-23559207.html.

Deng, X. (1979) 2008. “Socialism Can Also Develop a Market Economy (1979.11.26).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 2, 231–236. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1980) 2008. “Socialism Must First Develop the Productive Forces (1980.04–05).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 2, 311–314. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1982) 2008. “In the First Decade, Prepare for the Second (1982.10.14).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 16–18. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1985) 2008a. “The Reform and Opening-Up Is a Great Experiment (1985.06.29).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 130. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1985) 2008b. “Develop Democracy in Terms of Politics, Implement Reform in Terms of the Economy (1985.04.15).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 115–118. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1986) 2008. “Replies to the US Journalist Mike Wallace (1986.09.02).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 167–175. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1988) 2008. “Rationalise Prices and Accelerate Reform (1988.05.19).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 262–263. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1990) 2008. “Take Advantage of Opportunities to Solve Development Problems (1990.12.24).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 363–365. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1991) 2008. “Talks during an Inspection Tour of Shanghai (1991.01.28–02.18).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 366–367. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Deng, X. (1992) 2008. “Essentials from Talks Given in Wuchang, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shanghai (1992.01.18–02.21).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, vol. 3, 370–383. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Dubey, V. 1975. Yugoslavia: Development with Decentralization: Report of a Mission Sent to Yugoslavia by the World Bank. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dyba, K. 1989. “On a Socialist Market Economy—From a Czechoslovak Viewpoint.” Acta Oeconomica 40 (3–4): 219–221.

Engels, F. (1847) 1972. “Grundsätze des Kommunismus” [Principles of Communism]. In Marx Engels Werke [Marx and Engels Works], vol. 4, 361–380. Berlin: Dietz.

Engels, F. (1873) 1984. “Zur Wohnungsfrage” [The Housing Question]. In Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe [Marx and Engels Complete Works], vol. I.24, 3–81. Berlin: Dietz.

Engels, F. (1877) 1985. “Karl Marx.” In Marx Engels Gesamtaugabe [Marx and Engels Complete Works], vol. I.25, 100–111. Berlin: Dietz.

Engels, F. (1894) 1973. “Herrn Eugen Dührings Umwälzung der Wissenschaft (Anti-Dühring)” [Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science (Anti-Dühring)]. In Marx Engels Werke (Marx and Engels Works), vol. 20, 1–303. Berlin: Dietz.

Estrin, S. 1983. Self-Management: Economic Theory and Yugoslav Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fang, J. 2014. “Major Developments in the CPC’s Theory of Economic Well-Being since the Beginning of the Reform and Opening-Up—Deploying the Marxist Philosophical Method as the Main Line of Inquiry.” [In Chinese.] Studies on Marxism, no. 10: 58–67.

Gao, J., and M. Zheng. 1996. “The Philosophical Foundations of Deng Xiaoping’s Theory of a Socialist Market Economy.” [In Chinese.] Journal of the Xinjiang Institute of Education 31 (12): 1–4.

Gligorov, V. 1998. “Yugoslav Economics Facing Reform and Dissolution.” In Economic Thought in Communist and Post-Communist Europe, edited by H.-J. Wagener, 329–361. London: Routledge.

Horvat, B. 1969. An Essay on Yugoslav Society. Translated by H. Mins. London: Routledge.

Horvat, B. 1989. “What Is a Socialist Market Economy?” Acta Oeconomica 40 (3–4): 233–235.

Huang, N. 1994. “Philosophical Foundations of the Theory of a Socialist Market Economy.” [In Chinese.] Marxism and Reality, no. 11: 1–6.

Huo, B. 2011. “A Discussion of the Law of Value and Macro-Control under the Conditions of a Socialist Market Economy.” [In Chinese.] Capability and Knowledge, no. 27: 226–227.

Höhmann, H.-H. 1982. “Economic Reform in the 1970s—Policy with No Alternative.” In The East European Economies in the 1970s, edited by A. Nove, H.-H. Höhmann, and G. Seidenstecher, 1–16. London: Butterworths.

Jiang, Z. (1992) 2006. “Accelerate Reform, Opening-Up and Modernization and Achieve Greater Success in Building Socialism with Chinese Characteristics (1992.10.12).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Jiang Zemin, vol. 1, 210–254. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Kornai, J. 1959. Overcentralization in Economic Administration: A Critical Analysis Based on Experience in Hungarian Light Industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. 1986. “The Soft Budget Constraint.” Kyklos 39: 3–30.

Kornai, J. 1992. The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. 1993. “Market Socialism Revisited.” In Market Socialism: The Current Debate, edited by P. Bardhan and J. Roemer, 42–68. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kornai, J. 2006. By Force of Thought: Irregular Memoirs of an Intellectual Journey. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Kozma, F. 1982. Economic Integration and Economic Strategy. Translated by G. Hajdu and A. Bródy. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kraus, G. 1998. “Economics in Eastern Germany, 1945–90.” In Economic Thought in Communist and Post-Communist Europe, edited by H.-J. Wagener, 264–328. London: Routledge.

Kula, W. 1976. An Economic Theory of Feudalism: Towards a Model of the Polish Economy, 1500–1800. Translated by L. Garner. London: New Left Books.

Lange, O. 1936. “On the Economic Theory of Socialism: Part One.” The Review of Economic Studies 4 (1): 53–71.

Lange, O. 1937. “On the Economic Theory of Socialism: Part Two.” The Review of Economic Studies 4 (2): 123–142.

Le, D. 1960. “Leninism and Vietnam’s Revolution (20 April, 1960).” In The Socialist Revolution in Vietnam, vol. 1, 9–56. Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Le, D. 1963. “Enthusiastically to March Forward to Fulfill the First Five Year Plan (18 May, 1963).” In The Socialist Revolution in Vietnam, vol. 2, 171–212. Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Lenin, V. I. 1920. “Zamechaniia na knigu N. I. Bukharina ‘Ėkonomika perekhodnogo perioda’” [Marginal Notes on the Book by N. I. Bukharin, “The Economics of the Transitional Period”]. In Leninskii Sbornik [Lenin Collection], vol. 40, 383–432. Moscow: Institute of Marxism-Leninism.

Li, W. 2018. “Values and Social-Political Attitudes Among the Middle-Income Group.” [In Chinese.] Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Social Science Edition) no.6: 1–10.

Li, W. 2021. “Differentiating Between Middle Class and Middle-Income Group.” [In Chinese.] Social Sciences Digest no. 1: 56–58.

Li, Y., and E. Cheng. 2020. “Market Socialism in Belarus: An Alternative to China’s Socialist Market Economy.” World Review of Political Economy 11 (4): 428–454.

Lin, B. 1969. “Report to the CPC’s Ninth National Congress (1969.04.14).” [In Chinese.] http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64162/64168/64561/4429445.html#.

Liu, Z., and H. Liu. 2021. “Measurement Criteria and Changes in Size of the Middle-Income Group: An Analysis Based on CHNS.” [In Chinese.] Journal of Hebei University of Economics and Business 2021 (6): Online pre-publication.

Lo, C. 2007. Understanding China’s Growth: Forces that Drive China’s Economic Future. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lydall, H. 1984. Yugoslav Socialism: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Clarendon.

Malyshchev, I. V. 1955. “Proizvoditelʹnye sily i proizvodstvennye otnosheniia” [Productive Forces and Relations of Production]. In Bolshaia sovietskaia entsiklopediia [The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia], vol. 34, 2nd ed, edited by S. I. Vavilov and B. A. Vvedenskii, 628–630. Moscow: Gosudarstvennyi institut.

Mao, Z. (1937) 1984. “On Dialectical Materialism.” [In Chinese.] In Mao Zedong Works, Supplements, vol. 5, edited by T. Minoru, 187–280. Tokyo: Sōsōsha.

Mao, Z. (1937) 2009. “On Contradiction (1937.08).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 1, 299–340. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Mao, Z. (1945) 2009. “On Coalition Government (1945.04.24).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 3, 1029–1100. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Mao, Z. (1956) 2009. “The Goal of the Socialist Revolution Is to Liberate the Productive Forces (1956.01.25).” [In Chinese.] In Collected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 7, 1–3. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Mao, Z. (1957) 1977. “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People (1957.02.27).” [In Chinese.] In Selected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 5, 363–402. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Mao, Z. (1959) 2009. “The Law of Value Is a Great School (1959.03–04).” [In Chinese.] In Collected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 8, 34–37. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Marx, K. (1867) 2004. “Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Erster Band. Hamburg 1867” [Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 1, Hamburg 1867]. In Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe [Marx and Engels Complete Works], vol. II:5. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Marx, K. (1875) 1985. “Kritik des Gothaer Programms” [Critique of the Gotha Program]. In Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe [Marx and Engels Complete Works], vol. I.25, 3–25. Berlin: Dietz.

Marx, K. (1894) 1983. “Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Dritter Band. Hamburg 1894” [Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 3, Hamburg 1894]. In Marx Engels Gesamtausgabe [Marx and Engels Complete Works], vol. II:15. Berlin: Dietz.

Marx, K., and F. Engels. (1848) 1974. “Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei” [Manifesto of the Communist Party]. In Marx Engels Werke [Marx and Engels Works], vol. 4, 459–493. Berlin: Dietz.

Melzer, M. 1982. “The GDR—Economic Policy Caught between Pressure for Efficiency and Lack of Ideas.” In The East European Economies in the 1970s, edited by A. Nove, H.-H. Höhmann, and G. Seidenstecher, 45–90. London: Butterworths.

Mencinger, J. 2000. “Uneasy Symbiosis of a Market Economy and Democratic Centralism: Emergence and Disappearance of Market Socialism and Yugoslavia.” In Equality, Participation, Transition: Essays in Honour of Branko Horvat, edited by V. Franičević and M. Uvalić, 118–144. Houndmills: Macmillan.

Mises, L. von. 1932. Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis. Translated by J. Kahane. London: Jonathan Cape.

Nove, A. 1991. The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited. 2nd ed. Hammersmith: HarperCollins.

Nove, A., H.-H. Höhmann, and G. Seidenstecher, eds. 1982. The East European Economies in the 1970s. London: Butterworths.

Pareto, V. 1896. Cours d’économie politique [Course on Political Economy], vol. 1. Edited by F. Rouge. Paris: Pichon.

Pareto, V. 1902. Les Systèmes Socialistes [Socialist Systems]. Paris: V. Giard and E. Brière.

Peng, L. 1994. “The Philosophical Foundations of Deng Xiaoping’s Theory of the Socialist Market Economy.” [In Chinese.] Academic Research, no.2: 11–16.

Rusinow, D. 1977. The Yugoslav Experiment, 1948–1974. London: C. Hurst for the Royal Institute of International Affairs.

Stalin, I. V. (1952) 1997. “Ėkonomicheskie problemy sotsializma v SSSR” [Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR]. In Sochineniia [Works], vol. 16: 154–223. Moscow: Izdatelʹstvo “Pisatelʹ.