In the following analysis for Beijing Review, Carlos Martinez assesses British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s January visit to China as a significant moment in the recalibration of Britain-China relations amid accelerating geopolitical changes. The trip – the first by a British prime minister in eight years – signals a cautious thaw after a prolonged diplomatic “ice age” marked by security rhetoric, sanctions, and absurd propaganda.

Carlos contextualises the visit within Britain’s domestic economic pressures and the wider strain on the US-led international order. Accompanied by senior politicians and a broad business delegation, Starmer’s meetings with Xi Jinping and other senior Chinese leaders produced tangible outcomes, including visa-free entry, tariff reductions and new cooperation frameworks across trade, climate and education. The breadth of agreements reflects Britain’s urgent need for growth and investment in a stagnant economy.

The article argues that London’s previous hardening stance toward Beijing was driven largely by alignment with Washington’s containment strategy. However, as US pressure intensifies and transatlantic relations grow more volatile, the US’s traditional allies are starting to gradually reassess the extent to which their interests are served by subjugating themselves to Washington. China, by contrast, has proven itself to be a reliable advocate of multilateralism and mutually beneficial cooperation.

While resistance from US officials, British “China hawks” and sections of the media remains strong, the article contends that full Atlanticist alignment is increasingly untenable. Starmer’s visit, while bearing relatively modest fruit, reflects a broader shift toward multipolarity. Britain now faces a strategic choice: continue subordinating its interests to Washington, or adapt pragmatically to a world in which engagement with China is economically and politically unavoidable.

The Starmer visit is further explored in articles we posted on 4 February: Breaking the ice: Starmer’s pragmatic turn to China and Keir Starmer’s small-stick diplomacy.

British Premier Keir Starmer’s visit to China on January 28-31 was the first trip by a British prime minister to Beijing in eight years. It came at a time of uncertainty in both British domestic politics and international relations, reflecting wider geopolitical shifts.

Starmer was accompanied by a substantial delegation: senior politicians, including Business Secretary Peter Kyle, alongside around 60 representatives from the British business, finance, law, science, culture and higher education sectors. The breadth of the delegation in se was a signal that the visit went beyond mere symbolism and sought to re-establish close economic and diplomatic ties.

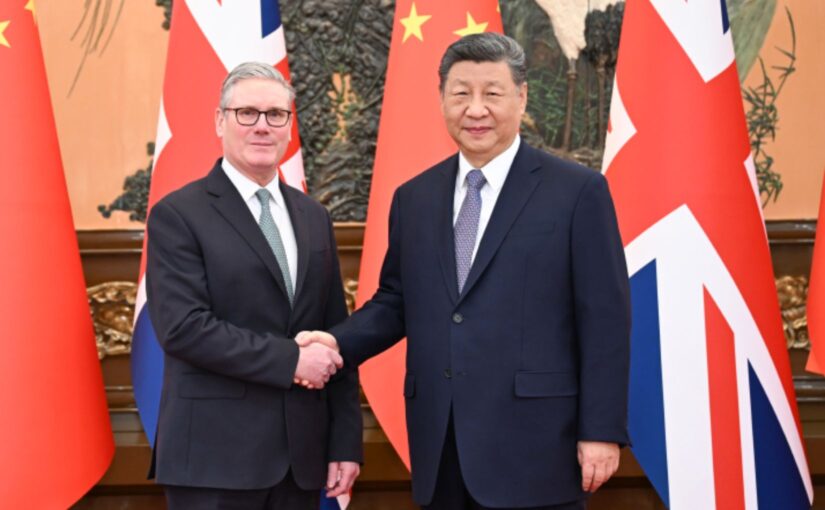

Starmer held extensive meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Premier Li Qiang and Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, China’s top legislature, Zhao Leji. Talks covered trade and investment, services, climate cooperation, financial regulation, people-to-people exchange and global affairs.

Concrete outcomes were announced, including a visa-free regime for short-term British travel to China, reduced Chinese tariffs on whisky, new cooperation frameworks in climate and nature, as well as a set of intergovernmental agreements spanning trade, agriculture, education, media and law enforcement.

The visit was part of an emerging diplomatic pattern: In recent weeks, Beijing has hosted a sequence of Western leaders, from Canada’s Mark Carney and Ireland’s Micheál Martin to Finland’s Petteri Orpo, with Germany’s Chancellor Friedrich Merz set to visit later this month. This flurry of engagement reflects a reassessment by U.S. allies of how to protect their own economic and strategic interests amid growing volatility in Washington.

From golden age to deep freeze

The significance of Starmer’s visit should be situated within the longer arc of Britain-China relations. The much-vaunted “golden age” proclaimed by David Cameron and George Osborne in the mid-2010s feels like a very long time ago. That period saw Chinese investment welcomed into different sectors of the British economy, including energy, infrastructure and telecommunications, in spite of persistent pressure from Washington, which had already embarked upon its “pivot to Asia” in 2011.

The golden age unraveled in the latter part of the 2010s, the victim of a perfect storm of growing U.S.-China tensions, the first Donald Trump administration’s aggressive unilateralism and the fallout from Brexit, which left Britain more economically vulnerable and dependent on Washington.

Over the subsequent eight years, relations slid into what Starmer himself has called an “ice age”: dominated by security rhetoric, sanctions, mutual suspicion and near-total diplomatic paralysis. Britain increasingly aligned itself with Washington’s strategy of containment, decoupling, slander and ideological confrontation, often at the cost of its own economic interests.

Recalibration

The current recalibration started to some degree under the previous British Government, headed by Rishi Sunak, with then foreign secretary James Cleverly referring to China as a potential “partner for good” and visiting Beijing in August 2023—the first visit to the country by a British minister since 2018.

However, Starmer’s Labour government has pushed this process substantially further, driven largely by its urgent need to break out of economic stagnation. Starmer came to power promising economic renewal, higher living standards and a green transition. Yet Britain’s growth rate is barely above zero, investment levels are weak and productivity growth is anemic. Compounding this, Labour’s poll ratings have slumped to historic lows, with the far-right Reform UK party exploiting public discontent and leveraging racist and anti-immigrant prejudices.

In such a context, cooperation with China is hugely important. The country is Britain’s fourth-largest trading partner, a vast market for goods and services, and a central node in the global supply chains for green technologies, electric vehicles, pharmaceuticals and advanced manufacturing. For a post-Brexit Britain still struggling to define its economic role, the idea that growth can be delivered while excluding meaningful engagement with China is frankly implausible.

Pressure from Washington – and from within

Yet any British move toward engagement faces fierce resistance. The U.S. continues to exert intense pressure on its allies to maintain a hard line on China, framing economic ties as security threats. Trump’s public criticism of Starmer’s visit—stating on January 30 that it’s “very dangerous” for the United Kingdom to do business with China—is a reminder of how quickly Washington moves to keep Britain in line.

Within Britain, China hawks in parliament, sections of the security services, and a largely hostile media environment amplify these pressures. Allegations of espionage and ritual denunciations over human rights dominate public discourse. As with Russia, China has become a convenient external villain—a way to deflect attention from domestic economic failure and political decay.

A shifting global context

The U.S. remains fixated on containing China, but its relationships with historic allies are under strain. Trump’s tariff threats, his open hostility to European strategic autonomy and his extraordinary threats regarding Greenland have deepened doubts about the sustainability of a U.S.-led world order.

China, by contrast, has time and time again demonstrated its commitment to peaceful coexistence, non-interference, respect for sovereignty, adherence to international law and mutually beneficial cooperation. Xi has been using his meetings with Western leaders to stress multilateralism and opposition to unilateral coercion, implicitly contrasting Beijing’s approach with Washington’s use of sanctions, tariffs and military aggression from Venezuela to Iran.

Carney captured this shifting mood in his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in late January, warning that “middle powers” must adapt pragmatically to a new reality in which the “great powers”—clearly referring to the U.S.—”have begun using economic integration as weapons, tariffs as leverage, financial infrastructure as coercion, supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited.”

This dynamic carries echoes of the past. In 1954, Mao Zedong told a visiting delegation of the British Labour Party that the U.S. sought to dominate an “intermediate zone” of countries, including Britain, with the objective of bullying them, controlling their economies, establishing military bases on their territories and seeing to it that they are increasingly weakened. Mao called on Britain to reject domination and pursue a sovereign course, engaging as equals with China for the mutual benefit of the British and Chinese people. “China, the Soviet Union, Britain and all other countries should move closer to one another. Defrost one’s views, and things will improve.”

The limits of Atlanticism

Ever since World War II, the so-called “special relationship” with the U.S. has shaped British foreign policy, security strategy and political culture. This has often meant subordinating British interests to those of Washington, even when they diverge sharply.

However, a full “Atlanticist” position—unquestioning alignment with U.S. strategy—is becoming increasingly and obviously untenable. Along with it, the narrative of wholesale “decoupling” from China is collapsing under the weight of economic reality. Even Washington’s closest allies now openly acknowledge that disengagement is neither feasible nor desirable.

Britain, however, remains more constrained than most. Brexit has narrowed its options, a hoped-for U.S. trade deal continues to loom large, security ties remain deeply embedded and the “special relationship” exerts a powerful gravitational pull.

As such, it’s highly likely that the other European capitals will progress further and faster toward partnership with China than London. Nonetheless, Starmer’s visit was a modest step in the right direction, opening space for mutually beneficial cooperation—in climate, health, education, science and trade—that Britain can ill afford to forgo.

Above all, the trip reflects the growing pains of an emerging multipolar reality. As the Cold War consensus dissolves, powers like Britain face a difficult choice: Cling to the U.S.’ fading hegemony, or adapt to a multipolar world.