In the following article, which was originally published in People’s Democracy, the weekly English-language newspaper of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPIM), Prabhat Patnaik takes up the contradictions in the view taken by parts of the western left with regard to China and its growing contradictions with US imperialism.

He begins by stating that, “significant segments of the non-Communist Western Left see the developing contradiction between the United States and China in terms of an inter-imperialist rivalry.” (One would just observe here that Comrade Patnaik is being either diplomatic or charitable, or quite possibly both, as a number of western communist parties, not least the Communist Party of Greece [KKE], are at least equally prone to this fundamental political error.)

Such a characterisation, Comrade Patnaik notes, “ironically makes these segments of the Left implicitly or explicitly complicit in US imperialism’s machinations against China… since the two countries are at loggerheads on most contemporary issues, it leads to a general muting of opposition to US imperialism.”

Comrade Patnaik further notes that this deviation is not new on the part of some sections of the left, citing attitudes to NATO’s bombing of the former Yugoslavia and current conflicts in both Ukraine and Gaza.

Regarding the claims that China is a capitalist country, Patnaik writes:

“As for China being a capitalist economy, and hence engaged in imperialist activities all over the globe in rivalry with the US, those who hold this view are, at best, taking a moralist position and mixing up ‘capitalist’ with ‘bad’ and ‘socialist’ with ‘good’. Their position amounts in effect to saying: I have my notion of how a socialist society should behave (which is an idealised notion), and if China’s behaviour in some respects differs from my notion, then ipso facto China cannot be socialist and hence must be capitalist. The terms capitalist and socialist however have very specific meanings, which imply their being associated with very specific kinds of dynamics, each kind rooted in certain basic property relations. True, China has a significant capitalist sector, namely one characterised by capitalist property relations, but the bulk of the Chinese economy is still State-owned and characterised by centralised direction which prevents it from having the self- drivenness (or ‘spontaneity’) that marks capitalism. One may critique many aspects of Chinese economy and society but calling it ‘capitalist’ and hence engaged in imperialist activities on a par with western metropolitan economies, is a travesty. It is not only analytically wrong but leads to praxis that is palpably against the interests of both the working classes in the metropolis and the working people in the global south.”

Hence:

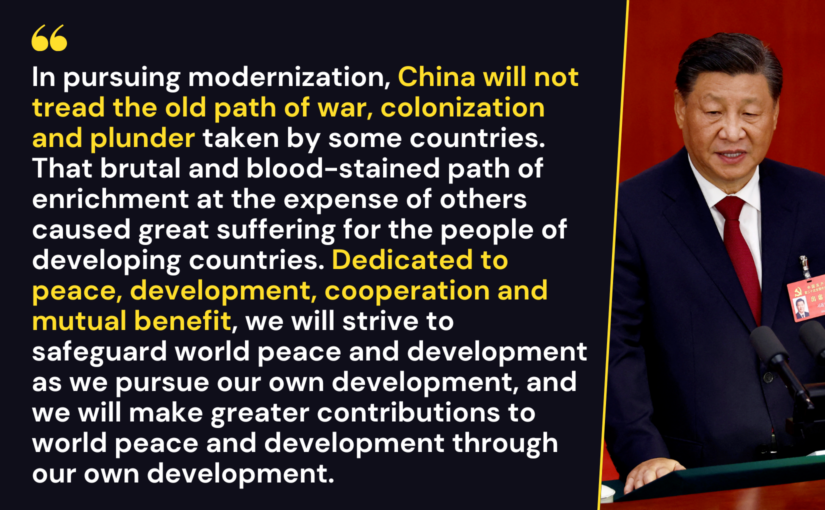

“It is not inter-imperialist rivalry, but resistance on the part of China, and other countries following its lead, to the re-assertion of hegemony by western imperialism that explains the heightening of US-China contradictions.”

Significant segments of the non-Communist Western Left see the developing contradiction between the United States and China in terms of an inter-imperialist rivalry. Such a characterisation fulfils three distinct theoretical functions from their point of view: first, it provides an explanation for the growing contradiction between the US and China; second, it does so by using a Leninist concept and within a Leninist paradigm; and third, it critiques China as an emerging imperialist power, and hence by inference, a capitalist economy, which is in conformity with an ultra-Left critique of China.

Such a characterisation ironically makes these segments of the Left implicitly or explicitly complicit in US imperialism’s machinations against China. At best, it leads to a position which holds that they are both imperialist countries, so that there is no point in supporting one against the other; at worst, it leads to supporting the US against China as the “lesser evil” in the conflict between these two imperialist powers. In either case, it leads to the obliteration of an oppositional position with regard to the aggressive postures of US imperialism vis-à-vis China; and since the two countries are at loggerheads on most contemporary issues, it leads to a general muting of opposition to US imperialism.

For quite some time now, significant sections of the western Left, even those who otherwise profess opposition to western imperialism, have been supportive of the actions of this imperialism in specific situations. It was evident in their support for the bombing of Serbia when that country was being ruled by Slobodan Milosevich; it is evident at present in the support for NATO in the ongoing Ukraine war; and it is also evident in their shocking lack of any strong opposition to the genocide that is being perpetrated by Israel on the Palestinian people in Gaza with the active support of western imperialism. The silence on, or the support for, the aggressive imperialist position on China by certain sections of the western Left, is, to be sure, not necessarily identical with these positions; but it is in conformity with them.

Such a position which does not frontally oppose western imperialism, is, ironically, at complete variance with the interests and the attitudes of the working class in the metropolitan countries. The working class in Europe for instance is overwhelmingly opposed to NATO’s proxy war in Ukraine, as is evident in many instances of workers’ refusal to load shipment of European arms meant for Ukraine. This is not surprising, for the war has also directly impacted workers’ lives by aggravating inflation. But the absence of any forthright Left opposition to the war is making many workers turn to right-wing parties that, even though they fall in line with imperialist positions upon coming to power as Meloni has done in Italy, are at least critical of such positions when they are in opposition. The quietude of the western left vis-à-vis western imperialism is thus causing a shift of the entire political centre of gravity to the right over much of the metropolis. And looking upon the US-China contradiction as an inter-imperialist rivalry plays into this narrative.

As for China being a capitalist economy, and hence engaged in imperialist activities all over the globe in rivalry with the US, those who hold this view are, at best, taking a moralist position and mixing up “capitalist” with “bad” and “socialist” with “good”. Their position amounts in effect to saying: I have my notion of how a socialist society should behave (which is an idealised notion), and if China’s behaviour in some respects differs from my notion, then ipso facto China cannot be socialist and hence must be capitalist. The terms capitalist and socialist however have very specific meanings, which imply their being associated with very specific kinds of dynamics, each kind rooted in certain basic property relations. True, China has a significant capitalist sector, namely one characterised by capitalist property relations, but the bulk of the Chinese economy is still State-owned and characterised by centralised direction which prevents it from having the self- drivenness (or “spontaneity”) that marks capitalism. One may critique many aspects of Chinese economy and society, but calling it “capitalist” and hence engaged in imperialist activities on a par with western metropolitan economies, is a travesty. It is not only analytically wrong but leads to praxis that is palpably against the interests of both the working classes in the metropolis and the working people in the global south.

But the question immediately arises: if the US-China contradiction is not a manifestation of inter-imperialist rivalry, then how can we explain its rise to prominence in the more recent period? To understand this we have to go back to the post-second world war period. Capitalism emerged from the war greatly weakened, and facing an existential crisis: the working class in the metropolis was not willing to go back to the pre-war capitalism that had entailed mass unemployment and destitution; socialism had made great advances all over the world; and liberation struggles in the global south against colonial and semi-colonial oppression had reached a real crescendo. For its very survival therefore capitalism had to make a number of concessions: the introduction of universal adult suffrage, the adoption of welfare State measures, the institution of State intervention in demand management, and above all the acceptance of formal political decolonisation.

Political decolonisation however did not mean economic decolonisation, that is, the transfer of control over third world resources, exercised till then by metropolitan capital to the newly independent countries; indeed against such transfers imperialism fought a bitter and prolonged struggle, marked by the overthrow of governments led by Arbenz, Mossadegh, Allende, Cheddi Jagan, Lumumba and many others. Even so, however, metropolitan capital could not prevent third world resources in many instances from slipping out of its control to the dirigiste regimes that had come up in these countries following decolonisation.

The tide turned in favour of imperialism with the coming into being of a higher stage of centralisation of capital that gave rise to globalised capital, including above all globalised finance, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union that itself was not altogether unrelated to the globalisation of finance. Imperialism trapped countries in the web of globalisation and hence in the vortex of global financial flows, forcing them under the threat of financial outflows into pursuing neo-liberal policies that meant the end of dirigiste regimes and the re-acquisition of control by metropolitan capital over much of third world resources, including third world land-use.

It is against this background of re-assertion of imperialist hegemony that one can understand the heightening of US-China contradiction and many other contemporary developments like the Ukraine war. Two features of this re-assertion need to be noted: the first is that metropolitan market access for goods from countries like China, together with the willingness of metropolitan capital to locate plants in such countries to take advantage of their comparatively lower wages for meeting global demand, accelerated the growth-rate in these economies (and only these economies) of the global south; it did so in China to a point where the leading metropolitan power, the US, began to see China as a threat. The second feature is the crisis of neo-liberal capitalism that has emerged with virulence after the collapse of the housing “bubble” in the US.

For both these reasons the US would now like to protect its economy against imports from China and from other similarly-placed countries of the global south. Even though these imports may be occurring, at least in part, under the aegis of US capital, the US cannot afford to run the risk of “deindustrialising” itself. The desire on its part to cut China “down to size” so soon after it had been hailing China for its “economic reforms” is thus rooted in the contradictions of neo-liberal capitalism, and hence in the very logic inherent to the reassertion of imperialist hegemony. It is not inter-imperialist rivalry, but resistance on the part of China, and other countries following its lead, to the re-assertion of hegemony by western imperialism that explains the heightening of US-China contradictions.

As the capitalist crisis accentuates, as the oppression of third world countries because of their inability to service their external debt increases through the imposition of “austerity” by imperialist agencies like the IMF, and in turn calls forth greater resistance from them and greater assistance to them from China, the US-China contradictions will become more acute and the tirades against China in the west will grow shriller.