The video below is an interview of Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez by Jason Smith, for CGTN’s The Bridge podcast. In this wide-ranging discussion, touching on a range of issues from the war in Iran to the nature of China’s whole-process people’s democracy, Carlos opines that “democracy” is not an abstract universal but always has a specific class content. What the West calls liberal democracy is more accurately described as capitalist democracy: a system in which the ruling class – those who own and deploy capital – dominates political life, and government is fundamentally oriented towards preserving existing production relations and expanding capital. As Marx observed, the oppressed are permitted once every few years to choose which representatives of the oppressing class shall govern them.

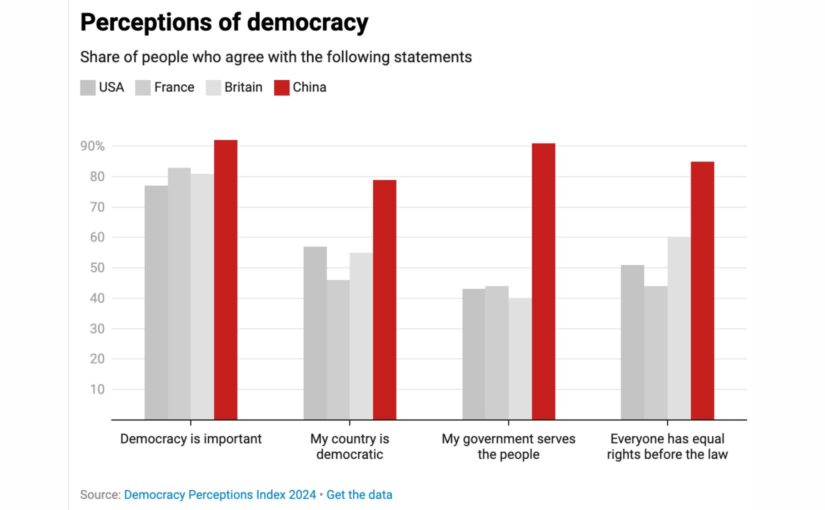

China operates a different democratic model suited to a different social system. The capitalist class cannot organise politically, cannot direct state power in its own interests, and cannot dictate to the government – for example, Huawei does not tell Beijing what to do. The Communist Party, with over 100 million members, is a party of the working class and its allies, obliged to maintain legitimacy by actually delivering – on poverty alleviation, healthcare, pollution control, housing, renewable energy and more. The result, borne out by polling data including a Harvard Kennedy School survey showing 94 percent government approval, is that Chinese citizens report far higher levels of satisfaction with their democracy than citizens of the US or Britain. The Two Sessions – the annual meetings of the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference – give concrete institutional expression to this whole-process people’s democracy, translating debates from across society into national policy, including this year’s 15th Five-Year Plan.

The US-China rivalry is not a conventional geopolitical contest between two comparable powers. The US helped integrate China into the global economic order in the late 1970s on the assumption that China would remain permanently at the bottom of the hierarchy – making cheap goods, opening up to Western capital, abandoning its socialist orientation through peaceful evolution. The reality has been entirely different: China is now the world’s largest economy, the leading force in renewables, telecoms, advanced infrastructure and space exploration, and is advancing an alternative model of modernisation that operates entirely outside the paradigm of imperialism – without war, occupation, austerity or the Washington Consensus. That is the real threat: not military aggression, but the ideological and material demonstration that another development path is possible. The hybrid war against China – sanctions, tech controls, military encirclement, demonisation – is aimed at preventing China’s further rise, weakening its global relationships, and ultimately reversing the Chinese Revolution. China, for its part, simply wants to develop and to cooperate.

The multipolar project is in essence a demand that the principles of the UN Charter – sovereign equality, non-interference, peaceful coexistence – be actually observed, not merely invoked rhetorically. The record of US-led imperialism in the postwar period, from the Korean War to the 1953 coup in Iran to the current wars on Venezuela and Iran, makes clear these principles have never been adhered to by Washington. Institutionally, multipolarity means strengthening the UN, building out BRICS, the SCO, the NAM and the G77+China, developing alternative financing, and expanding south-south cooperation backed by China’s economic weight and the Belt and Road Initiative. This project increasingly has institutions, momentum and a trajectory – though it faces the enduring obstacle of US military hegemony and the reckless aggression of a declining empire.

For those in the West who want to engage constructively, the starting point is to resist the war propaganda that saturates mainstream media, tell the truth about China, and actively participate in anti-war movements – making the case for maximum global cooperation on climate, peace and development.