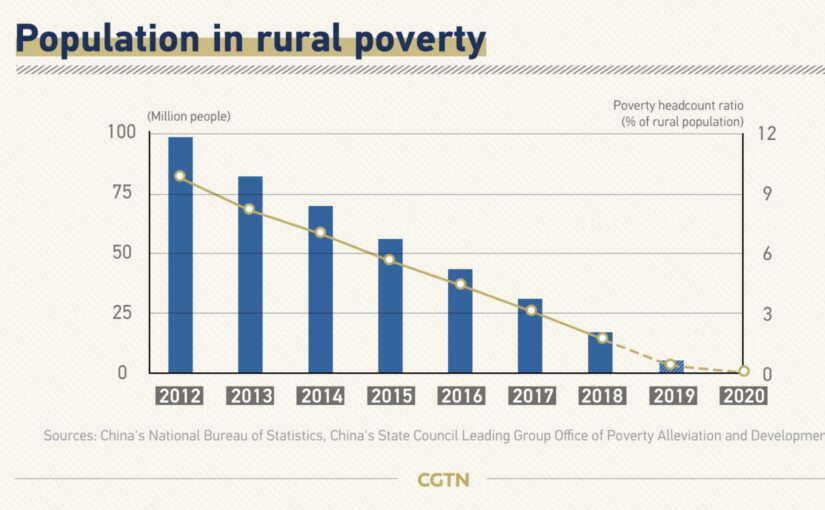

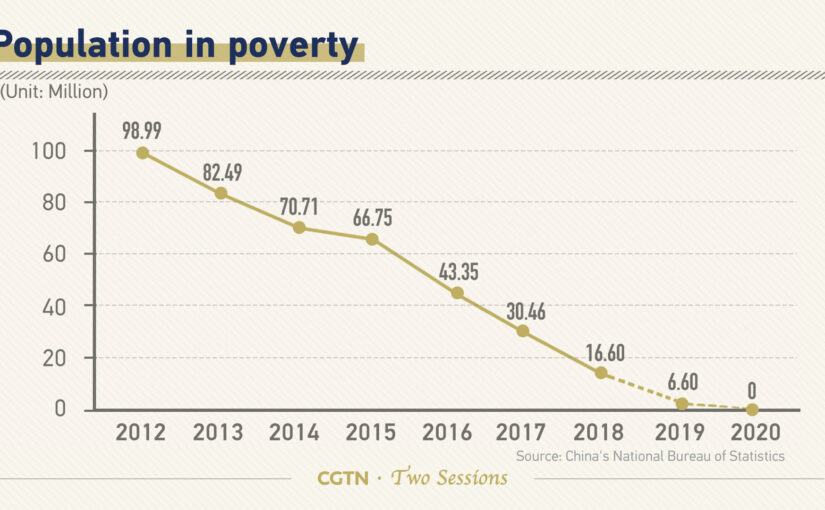

In recent years, public discussion about China in the United States – and the West more generally – has been dominated by accusations, slander, McCarthyite fear-mongering and geopolitical posturing. The relentless anti-China narrative has meant that one of the most consequential social achievements of the modern era has been almost entirely ignored: China’s eradication of extreme poverty.

As global inequality deepens and economic insecurity becomes a defining feature of life for millions in the West, the refusal to seriously examine how China transformed the lives of hundreds of millions of people is a consequential political failure.

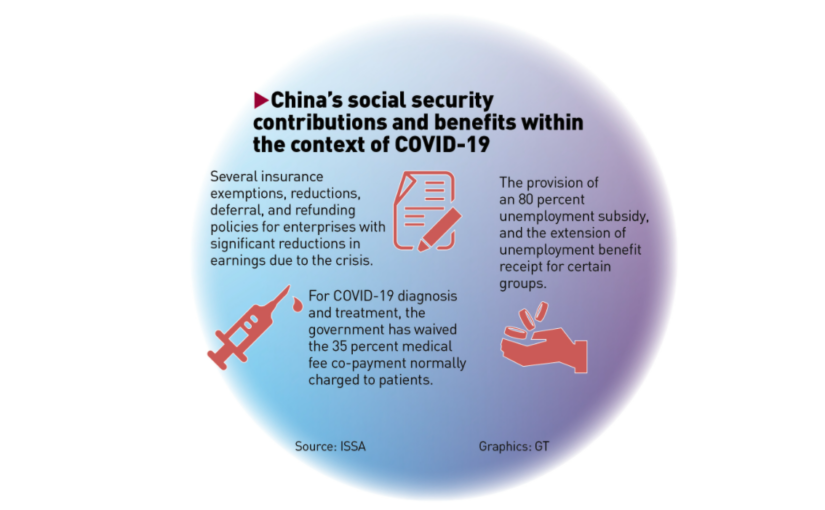

Megan Russell’s article for CODEPINK, republished below, confronts this silence head-on by juxtaposing two starkly different realities. On the one hand is the growing exposure, even within China itself, of the fragility of life in the US – a society where healthcare, housing and survival itself often rest on a razor-thin margin. On the other is China’s systematic, state-led effort to ensure its entire population can enjoy fundamental human rights: a minimum income level, guaranteed housing, adequate food and clothing, free healthcare, universal education, running water and access to modern energy.

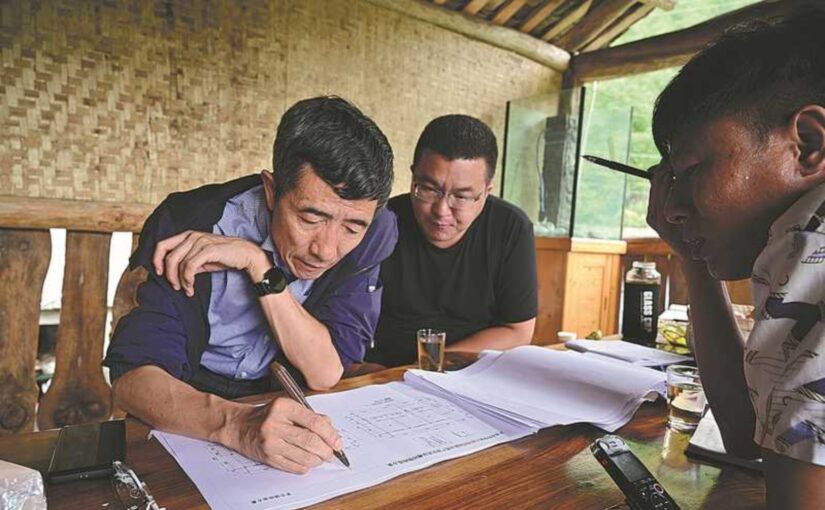

Rather than treating poverty as an individual moral failing, China approached it as a structural problem requiring coordinated national action, public accountability and sustained investment in human well-being. The result has been the largest poverty alleviation campaign in human history.

Megan argues that the suppression of these facts in the US – through media omission, political censorship and ideological hostility – prevents meaningful learning at a moment when it is urgently needed. If global cooperation is to replace confrontation, and human needs are to take precedence over militarism and profit, then China’s experience must be examined honestly, not buried. The article concludes:

We need to stop funneling vast resources into military expansion and foreign intervention. We need to prioritize the needs of the people over the profits of the elite. We need to end preparations for a war on China and the propaganda campaigns that justify it. Most importantly, we need the United States, China, and the rest of the world to work together to end global inequality and ensure a just and sustainable future for all. If this does not happen, we will all face the consequences.

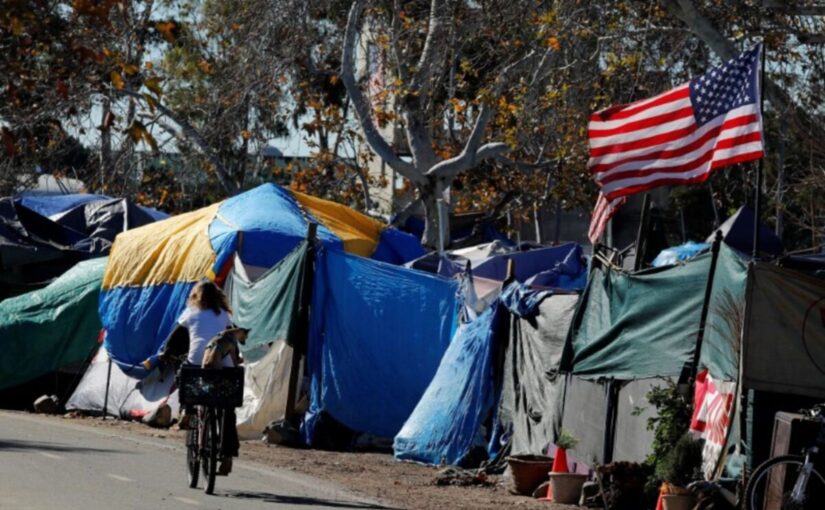

Over the past month, Chinese social media platforms like Xiaohongshu and Bilibili have begun dismantling the myth of the “American dream,” replacing glossy imagery with firsthand accounts showing that life in the so-called “land of the free” is far from bright and picturesque. In its place, a new concept has emerged, borrowed from video games, when a character’s health drops so low that a single hit can end everything. It’s called the “kill line,” and the term has rapidly entered mainstream political discussion in China.

The “kill line” describes the fragile margin of survival in the lives of many Americans, where one medical emergency, job loss, or unexpected expense can push a person into homelessness or permanent poverty. This precarious balance is a constant threat embedded in the structure of a society that prioritizes profit over people. One mistake, one illness, or one stroke of bad luck can place someone’s entire life in jeopardy.

Continue reading Ignoring China’s poverty alleviation success is costing us all