This insightful article by CGTN reporter Zhou Jiaxin, first published in the Morning Star, analyses the increasingly hostile rhetoric employed by US politicians in relation to China – in particular that China is undermining the “rules-based international order”. Such rhetoric provides a cloak for expanding NATO’s scope to the Pacific and for developing anti-China military alliances such as AUKUS and the Quad. Zhou Jiaxin contrasts the aggressive actions of the US and its allies with China’s consistent multilateralism, its support for organisations such as BRICS, its emphasis on cooperation, and its role in “counterbalancing and reshaping the world into one that is no longer dominated by only Western powers”.

When USAF C-17 took off from Kabul International Airport last year, shocking videos showed people plunging to their deaths as hundreds of Afghans tried to cling onto the final departing flight. It marked the bloody and chaotic end to the US’s longest war overseas.

Almost a year later, the world order remains threatened by what Beijing calls the politics of “small circles” — and this is creating confrontation and insecurity.

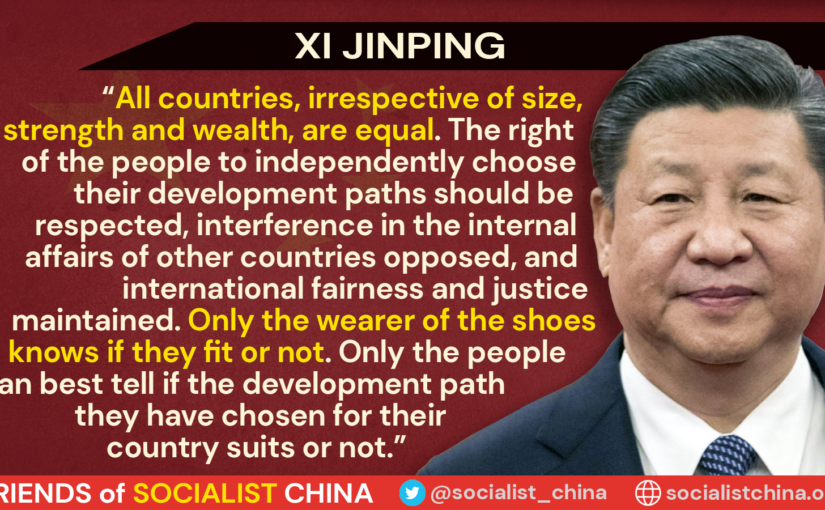

“Some countries are now seeking absolute security via expansion of military alliances to force other countries to take sides and create bloc confrontation, to overlook other countries’ interests and rights and seek supremacy,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said at the latest Brics summit, attended by major developing countries Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa.

The message from Beijing closely follows rhetoric from Moscow that has described six rounds of Nato eastward expansion as a threat amid Ukraine’s anticipated accession to the military bloc.

When finally the Kremlin’s demand that Kiev not be allowed to join Nato went ignored, Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his “special military operation” in Ukraine. Russian troops have since taken control of Ukraine’s eastern region that borders Russia.

There’s no sign yet when Moscow and Kiev will resume peace negotiations. But given continuous military support from Nato, in particular heavy weapons and aid of more than $7 billion from the US, it is Brussels and Washington — not Kiev — who could weigh more when it comes to a ceasefire.

At the Nato public forum, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken accused China of seeking to undermine the rules-based international order, saying the US and its allies are its upholders and not looking for conflict.

But Washington has called China a “competitor” in the Indo-Pacific and established its own bloc in the region, alongside Japan, India and Australia. The group known as the Quad is sometimes seen as an “Asian Nato” — an attempt to counter China. The Nato summit in late June even saw South Korea invited to join the anti-China coalition for the first time.

“If such dangerous trends are allowed to continue, the world will witness even more turbulence and insecurity,” Xi said at the Brics summit.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian has called these developments an attempt to “mislead the public.”

“The US has worked hand in glove with Nato to hype up competition with China and stoke group confrontation,” he told journalists — however, he continued, “The narratives and gambits that the US employs are not so clever.”

From Bosnia and Herzegovina to Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, Nato has been accused of creating conflict and waging wars that have turned into grave humanitarian disasters, with 400,000 civilians killed since 2001 and tens of millions displaced.

“Even to this day, there is no sign of change,” Zhao said. “Facts have proven that it is not China that poses a systemic challenge to Nato, but Nato that brings a looming ‘systemic challenge’ to world peace and security.”

Beijing has repeatedly pointed out that it has never invaded another country nor launched proxy wars, nor participated in or put together any military blocs.

It has always seen what the US calls the “rules-based international order” as a bunch of rules made by a small circle of countries to serve the interests of the US in seeking hegemony.

For example, the G7 summit in late June concluded with a “leaders’ communique” targeting China on matters concerning Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Taiwan — despite China’s firm opposition.

“The ‘democracy versus authoritarianism’ narrative keeps the world entrenched in a cold-war mentality,” Zhao said in response to the communique. “We urge the G7 to earnestly step up to its responsibility and due international obligations, uphold true multilateralism, and stop applying double or even multiple standards,” he said at the Foreign Ministry daily press conference.

Beijing has emphasised the success of Brics. In his speech at the latest summit, Xi said that, despite the challenges of Covid-19 and increasingly salient peace and security issues, Brics countries have remained “open and inclusive.” He called on members to act with a sense of responsibility to bring positive, stabilising and constructive strength to the world.

“We need to speak out for equity and justice,” Xi said. “We need to encourage the international community to practice true multilateralism.”

Brics leaders have pledged to play a leading role in driving global economic growth in the post-pandemic era. The mechanism has been lauded over the years as not just a talking shop but as the new leader of global governance.

Set up in 2009, Brics represents 40 per cent of the world population, accounts for 25 per cent of the global economy and contributes 50 per cent to the world’s economic growth.

These major economies have helped counterbalance and reshape the world into one that is no longer dominated by only Western powers. Within this multipolar world, shared security and prosperity can be only achieved though co-operation, not “small circles” politics built around hegemony.