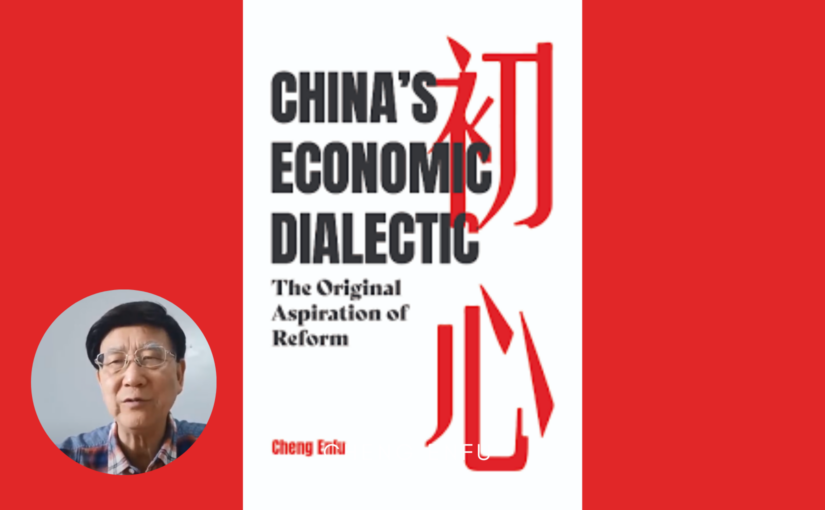

We are pleased to republish Andrew Murray’s thoughtful and critical review of ‘China’s Economic Dialectic’, a recent book by Cheng Enfu, one of China’s foremost Marxist scholars, published by New York-based International Publishers. It was originally published in the Morning Star.

Andrew begins by noting that “there are few more important endeavours for the international left than understanding China’s extraordinary development and its meaning for world socialism,” and bemoans the general lack of reference to the work of Chinese scholars and the Communist Party of China in this regard.

Noting that Professor Cheng “locates the present mix of public ownership with substantial private enterprise and preponderant market relationships as appropriate for the primary stage of socialism, but looks forward to advancing to a fully public model to be attained under advanced socialism and finally communism,” Andrew points out that the author is “far from blind to the problems that have emerged as a result of the reforms” and “not afraid to criticise the Chinese government from within a position of overall support.”

In outlining his view of the shortcomings in Cheng’s work, Andrew cites a lack of “real reflection on the strengths and shortcomings of the ‘planned product economy’ as it actually existed in the USSR and in China itself until 1978.”

In conclusion he recommends it as “rewarding for those wanting to really grapple with the exceptional dynamics of China’s development and its socialist nature.”

The editors of this website do not necessarily agree with all of Andrew’s observations and assertions, but we unequivocally welcome the serious attention given to this subject by one of Britain’s most erudite Marxists and his contribution to a vital debate.

AS THE late Giovanni Arrighi stated: “If China is socialist or capitalist it is not like any previously encountered model of either,” and there are few more important endeavours for the international left than understanding China’s extraordinary development and its meaning for world socialism.

Such work is often bedevilled by an over-reliance on Western-generated analyses of China, as if the studies and understandings of Chinese scholars and the Communist Party of China themselves were of little use.

Cheng Enfu’s book is extremely helpful in this context. Cheng is a leading Chinese Marxist academic who has clearly thought deeply about China’s development as a socialist state.

His book examines economic policy in China from a variety of angles.

He locates the present mix of public ownership with substantial private enterprise and preponderant market relationships as appropriate for the primary stage of socialism, but looks forward to advancing to a fully public model to be attained under advanced socialism and finally communism.

Correctly, he claims that “the tremendous achievements China has realised during its 30 years of reform and opening up are not the result of following Western mainstream economics, or of implementing policies the derive from it”, and not least in respect of making the finance sector serve the productive economy.

But Cheng is far from blind to the problems that have emerged as a result of the reforms, including large-scale privatisation, that were first embarked upon in 1978 and intensified significantly from 1992.

He draws attention to China’s world-leading standards of inequality between rich and poor, and points out the falling share of income accruing to labour over two generations associated, as he acknowledges, “with the rapid growth of capital income.”

He attributes much of this to the decision to promote China for many years as a centre of low-wage production for foreign investors. “Today… the era when China could compete on the basis of low labour costs has passed.”

Cheng is not afraid to criticise the Chinese government from within a position of overall support. For example, he writes that “the opening up of the auto industry in China has been an obvious failure, and the large aircraft industry an even bigger one” because foreign involvement disrupted strong indigenous development and research activities.

More public ownership over the medium to long term is the solution Cheng favours. “A future socialist society must fundamentally eliminate capitalism by rooting out the system of private property ownership on which social exploitation depends,” he writes.

He also champions, rightly in my view, the policy of “common prosperity” as being synonymous with the basic premises of socialism. It is “a realistic path for China’s socialist modernisation drive and a concrete manifestation of the institutional advantages China has achieved through the establishment of our socialist system.”

One issue that Cheng repeatedly raises but that requires further examination is his belief that public ownership guarantees distribution according to work. It is clear that the latter cannot be attained except through public ownership, but it is not so clear, to this reviewer at least, that public ownership is sufficient in itself to secure distribution by work if it is operating in a commodity exchange economy.

China today, he argues, is a “planned commodity economy”, yet in another passage he asserts that “a decisive role must be assigned to the invisible hand in the allocation of general resources, at the same time recognising the leading role of governments at all levels.”

Here is an inherent and continuing struggle, which Cheng sees as ultimately resolved in the transition to a “planned product economy” in which the law of value is no longer operative.

Here are two shortcomings of Cheng’s stimulating book.

First, there is no real reflection on the strengths and shortcomings of the “planned product economy” as it actually existed in the USSR and in China itself until 1978. Both achieved spectacular growth rates alongside undoubted difficulties in shifting to intensive production and qualitatively superior rates of productivity. How will those problems be avoided “second time around”, as it were, in China?

Second, how is this transition to advanced socialism to be effected?

In common with many Chinese Marxists the role of class struggle is ignored. Cheng’s introductory definition of Marxism does not make even a passing mention of it.

This reticence on the subject of class is doubtless a reaction to the disastrous abuse of the concept of class struggle that characterised CPC policy in the period of the Cultural Revolution, 1966 to 1976.

Nevertheless, the absence disables the analysis of contemporary Chinese society. Just this month we can read of disturbances in one province by migrant workers over unpaid wages, where the local government supported the employers; and demonstrations by pensioners in another over government cuts to medical benefits.

It is still more disabling when considering the forces that could lead to Cheng’s desired transition to advanced socialism and communism. Merely relying on the beneficence and wisdom of the CPC leadership, directing a heterogeneous class society, does not seem sufficient. One cannot positively direct the class struggle if one doesn’t acknowledge its existence.

This is a challenging book and may not be for the general reader. However, it is rewarding for those wanting to really grapple with the exceptional dynamics of China’s development and its socialist nature.

From your review of Cheng Enfu’s book, it appears to be a long exposition and implicit endorsement of the Menshevik theory of productive forces: a country must develop industrial capitalism before it can become socialist. But you do not say it; your ratio of praise versus critique is upside down.

The Menshevik stageism isn’t simply about the need for developing industrial capitalism to advance to socialism. That was something done by the NEP (which was perhaps too short-lived out of historical necessity at the time). The Mensheviks thought that Russia couldn’t have a proletarian revolution and a socialist superstructure until it goes through the stage of bourgeois revolution and industrial capitalism. China has a socialist superstructure and a socialist base, but carrying the birthmarks of the capitalist mode of production which they develop beyond.