In this concise review of Carlos Martinez’s The East is Still Red, Graham Harrington summarises the book’s main arguments, describing it as a “very readable and able defence of the current People’s Republic of China.”

Graham notes that, while the socialist market economies of China and Vietnam are controversial among many Marxists in the West, it is important to recognise these countries’ achievements – particularly in relation to poverty alleviation – and to assess them from a position of humility. “Given the lack of any revolution in the West, we should perhaps not be so dismissive of what has been achieved in China, or look at China from an ivory tower.”

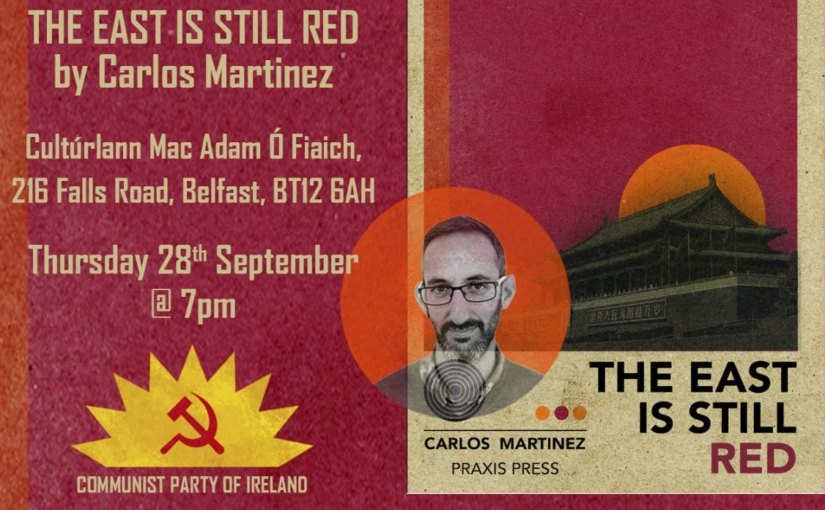

The review originally appeared in Socialist Voice, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of Ireland (CPI).

The CPI is hosting book launches for The East is Red at Connolly Books, Dublin, on Wednesday 27 September 2023, and Cultúrlaan Mac Adam Ó Fiach, Belfast, on Thursday 28 September 2023.

For those based in the EU, Connolly Books is the best place to order a paperback copy. Elsewhere, we recommend buying from Praxis Press.

The East Is Still Red is a very readable and able defence of the current People’s Republic of China. The basic argument of the book is that China is on the right path with regard to building socialism, despite the controversy a statement like this causes among the Western left.

The Chinese Revolution of 1949 put an end to what Chinese call their “century of humiliation,” the period of the Opium Wars, Japanese colonialism, famine, and warlord rule. It was also the culmination of decades of struggle by the Communist Party of China, which had endured massacres and guerrilla struggle before the revolution.

The new People’s Republic managed to unite the country, double the life expectancy of China’s people, end horrific misogynist practices such as foot-binding in some areas, and eliminate landlordism and inequality. This was despite failures and mistakes, such as the Great Leap Forward.

For the author, China’s achievements are not just historical but in fact continue to this day. The reform and opening-up period did not mark a break with socialism in China. At the time of Mao’s death the People’s Republic had achieved many advances. Its economy had impressive successes in heavy industry, but the majority of its people continued to languish in objective poverty, and it was this fact that made the CPC examine the direction of the country.

Essentially, the argument of the CPC for reform was that if poverty remained in the country it would threaten socialism. In the 1970s China’s neighbours, including Japan, South Korea, and Malaysia, were experiencing economic booms, while China’s citizens lived on state rations. The leadership felt that this was a threat to the existence of the People’s Republic. Foreign investment was encouraged, as was a domestic private sector. The rest is history. China is now the world’s second-largest economy.

Despite the huge increase in inequality, the author argues that the reforms were still necessary for development and people’s needs. The strongest argument for this is that China has taken some 800 million citizens out of absolute poverty. The reforms did indeed create billionaires, but they also eliminated absolute poverty. If China is capitalist, then this presents major challenges to the Marxist understanding of capitalism.

We may add the existence of the second economy in the socialist states, past and present, as documented in Roger Keeran and Thomas Kenny’s book Socialism Betrayed (2010). The second economy incorporated the black market, those who hoarded state-subsidised goods and in effect provided the material basis for the destruction of socialism in the country where it was born. In no country today is there a perfect socialism, where there is no private sector or markets. Martinez writes how carefully the Chinese leadership analysed the defeat of the USSR.

Along with several quotations from Mao in the PRC’s early days, Martinez gives a quotation from Lenin in 1921 to show how the CPC’s post-reform thinking was not something new: “What we must fear is protracted starvation, want and food shortage, which create the danger that the working class will be utterly exhausted and will give way to petty-bourgeois vacillation and despair.”

While China’s recent trajectory is not popular among leftists in the West, the author believes it should perhaps give us some reason to examine how Western leftists can over-idealise socialism into a utopia, while countries such as China or Vietnam have to provide for their people’s basic needs after decades of imperialist underdevelopment. Given the lack of any revolution in the West, we should perhaps not be so dismissive of what has been achieved in China, or look at China from an ivory tower.

The environment, and specifically China’s response, is looked at in a very important chapter of the book. While China’s economic boom produced much pollution, China now produces more solar panels than any other country, and is first in investment in renewable energy. It has also doubled its forest coverage.

Additionally, it is noted that China’s pollution cannot be compared with historical pollution by the likes of the United States and Britain. Per capita, China’s emissions are similar to those of Ireland and Austria. A huge amount of greenhouse gas emissions is in fact caused by production for Western consumption: American and Canadian households emit nine times the emissions of the average Chinese household. In effect, the West has exported its polluting to China, leaving it with the blame.

The book does not pretend to be a comprehensive overview of China, nor a justification of every policy taken. It seeks to examine China and explain why we need to examine it seriously, not rating it out of ten but instead seeing how China has remained much closer to its original path than Western leftists believe it to be.