The London Region of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) held its 2025 Annual Conference online on Sunday 12 January.

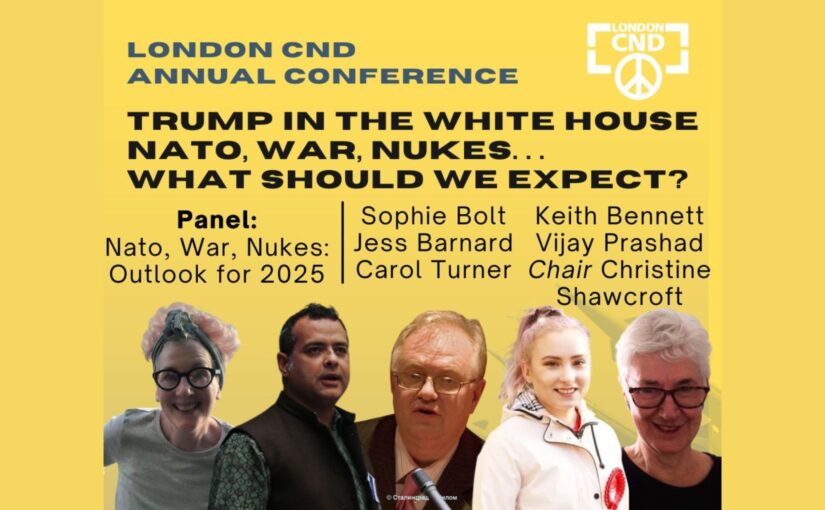

Friends of Socialist China co-editor Keith Bennett was among the speakers in a session entitled, NATO, war, nukes: Outlook for 2025, where he was joined by CND General Secretary Sophie Bolt; Jess Barnard, a member of the Labour Party’s National Executive Committee (NEC); Carol Turner, Chair of London CND and a Vice Chair of national CND; and Vijay Prashad, Director of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research. The session was chaired by Christine Shawcroft, a Vice Chair of London CND and editor of Labour Briefing.

A keynote opening speech on Prospects for Peace and Justice was given by Jeremy Corbyn, former Leader of the Labour Party and now the Independent Member of Parliament (MP) for Islington North, introduced by Murad Qureshi, a Vice President of London CND and a former Chair of the Stop the War Coalition.

Further discussions focused on Ukraine and the Middle East as testing grounds for new tech weapons, with expert input from Peter Burt, a researcher for Drone Wars UK; and Dave Webb, Convenor of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space; chaired by former MP Emma Dent-Coad; and a final session on Peace Movement Priorities, with Baroness Jenny Jones from the Green Party; Tony Staunton, a Vice Chair of CND; and Angie Zelter, a founder of Lakenheath Action for Peace; chaired by Hannah Kemp-Welch, a Vice Chair of London CND.

Keith’s speech focused on the prospects for relations between China and the United States during Donald Trump’s second presidency. We reprint it below.

An edited version was also carried by Labour Outlook. The full conference proceedings can be viewed on the YouTube channel of London CND.

Thank you to London Region CND for the invitation to take part in this distinguished panel.

With war raging in Ukraine for nearly three years and with the unrelenting genocide in Gaza, now well into its second year, both naturally forming the main day-to-day focus of most peace campaigners, is it self-indulgence or overreach to also turn our attention to the Asia Pacific region?

I would argue that it is not. No analogy is ever exact, but a clear parallel can be drawn with events in the 1930s. Local conflicts, in Spain, Ethiopia and, indeed China, were the proverbial canaries in the mine, which presaged the global conflagration of World War II.

Today, no bilateral relationship is more important, more strategic and more fraught than that between the United States and China. On the potentially positive side, the world needs these two powers to work together constructively if humanity is to meet an existential threat like climate change. Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of China, and of a couple of US politicians, there is little sign of this happening. Something that will most likely be exacerbated when Trump quits the Paris Climate Change Accord. Again.

Faced with the peaceful rise of China, a rise unparalleled in human history, it has essentially become a consensus among the otherwise contending wings of the US ruling class that the preservation of US global hegemony necessitates taking China as Washington’s principal adversary. From Greenland to the South Pacific. And from semiconductors to TikTok. And increasingly throughout the Global South. A New Cold War which, like its predecessor, can all too easily turn hot.

As with Cold War One and the Soviet Union, the US seeks to reverse China’s progress and, at best, bring it to heel, through a combination of a debilitating arms race, ideological subversion and economic and technological strangulation. A key difference is that not only has China drawn lessons from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Whereas the USA and the USSR were essentially economically insulated from one another, China has spent the best part of half a century integrating itself into the global economy, creating such facts on the ground in the process as ever more complex global supply chains, and with China accounting for some 11% of US foreign trade.

So, what does Trump’s return mean for China/US relations?

First, Trump revels in his role as Disruptor-in-Chief, so the first thing we should expect is the unexpected. Certainly, if he carries through on even a fraction of his recent threats regarding tariffs, not only will China face an economic challenge. The entire global economy, in a parlous enough state as it is, and not least the US economy itself, will be plunged into crisis.

But overall, there seems little reason to anticipate a fundamental change of direction. When Biden assumed the presidency, many had hopes for a return to a more rational and constructive China policy in Washington. This did not materialise. Far from reversing Trump’s anti-China measures, the Biden administration ratcheted them up substantially, especially in terms of trying to restrict China’s access to computer chips and other advanced technology.

To the extent there was change under Biden, it came essentially in two areas:

- His administration largely eschewed the openly racist rhetoric of Trump (kung flu, Chinese virus, etc.), which undoubtedly made life more tolerable for many Chinese and other Asian and Pacific Islander Americans.

- Whereas Trump was an ‘equal opportunities bully’ when it came to insulting and threatening allies and adversaries alike, Biden’s team worked hard, and with a considerable degree of success, to reinforce cohesion in NATO, get the EU onside, and reinvigorate and reinforce old alliances, such as those with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines, all with a view to confronting China, along with Russia, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and other states in Washington’s crosshairs.

So, even if Trump ups the ante with China, it will not break the essential continuum established by Barack Obama and Hilary Clinton with their 2011 ‘pivot to Asia’.

One reason why Trump presents as the Disruptor-in-Chief is that his opinion on any given question so often appears to be that of the last person he happened to have spoken to. The ‘team of rivals’ he has been assembling certainly lacks the intellectual brilliance of that forged by Abraham Lincoln, but it is not monolithic on China.

Trump himself cares little for ‘liberal democracy’ and, on that level, his antipathy to China probably lacks the deep ideological foundation that the US Democratic Party has come to increasingly embody. His motivation is more straightforwardly venal. He will fight ruthlessly but may be prepared to cut a deal if he feels the terms are good. Or, perhaps as importantly, can present it as a win. We need to think only of his current stance on TikTok, doubtless related to its ability to help feed his social media obsession.

The same cannot be said for his proposed Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who clearly will not be satisfied with anything less than the overthrow of the Communist Party of China.

A similar orientation can be seen on the part of a number of Trump’s other nominees, including those to be given trade or related portfolios.

But this, in turn, is different from the stand of Trump’s current ‘bestie’ (although for how long is anyone’s guess) Elon Musk, whose Shanghai factory accounts for half of Tesla’s global production.

In a sense, the fissure this creates between Musk on the one hand and a long-established Trump acolyte like Steve Bannon on the other mirrors the recent dispute over H-1B high skilled visas between Trump supporting plutocrats and the MAGA base.

Another area where this pattern can be expected to assert itself is in diplomacy and hence on the international balance of forces. As mentioned, while the Biden administration strove, with considerable success, to unite the imperialist camp, in the case of Trump, from Angela Merkel to Justin Trudeau, if there’s one thing he seems to enjoy more than insulting America’s adversaries it’s insulting America’s allies.

How this will play out remains to be seen. Just yesterday, two of the headlines in the South China Morning Post, Hong Kong’s well-respected English language daily, read as follows:

- Ishiba’s snub by Trump may push Japan toward China, sparking concerns about US influence (Ishiba is the current Japanese Prime Minister); and

- US national security adviser fears Trump might push some Indo-Pacific nations toward China

The Asia Pacific region is where key issues still unresolved from the 1940s continue to fester and where the interests of nuclear powers, principally the United States, China, Russia and the DPRK, collide and at times coincide. How will Trump, in his second presidential term, react to tensions in the Taiwan Straits or the South China Sea?

On the Korean peninsula, will he once again resort to threats of unleashing “fire and fury” or will he seek a further meeting with Kim Jong Un, something no other serving US president dared to do?

Answers to such questions will have a major bearing on the future of the world.