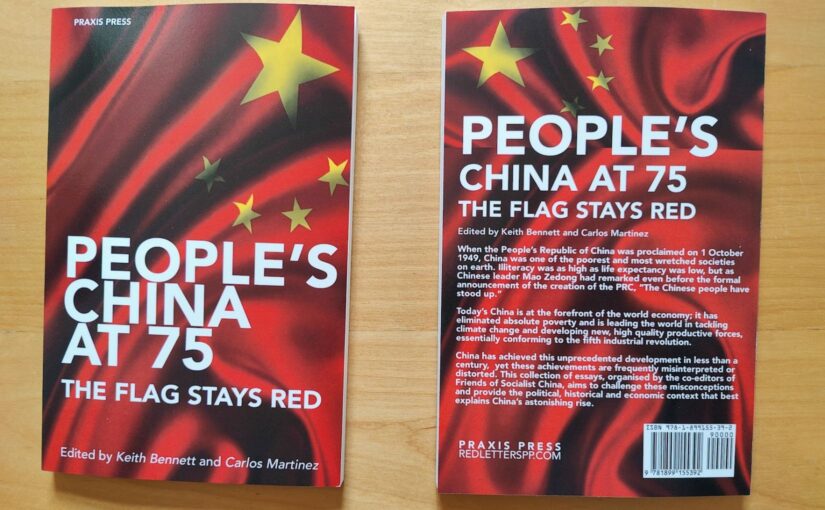

We are very pleased to republish below a comprehensive review by Gabriel Rockhill of “People’s China at 75: The Flag Stays Red”, edited by Keith Bennett and Carlos Martinez, the co-editors of this website, and published by Praxis Press.

Recalling how Lenin rejoiced when the October Revolution outlasted the Paris Commune, Gabriel notes: “Karl Marx, writing on these events at the time, celebrated the unprecedented advances of the workers’ movement while lucidly identifying its principal limitation: it had not crushed the bourgeois state and founded a proletarian state capable of defending its interests. This is a lesson that Vladimir Lenin had taken to heart, and his reputed dance in the snow feted the practical success of a correct theoretical assessment.”

On October 1st, 2024, for which anniversary this book was published, the People’s Republic of China eclipsed the longevity of the Soviet state.

How should those “who support the struggle for a more egalitarian and ecologically sustainable world” respond?

Gabriel notes that the book “seeks to respond to these questions and others through rigorous materialist analysis and a coherent theoretical framing of the PRC’s place in world history. Comprised of eleven incisive analyses framed by a capacious introduction, the book serves as a useful guide to anyone interested in a crash course on China by some of the world’s leading experts on the question. Given its readability, with concise essays and a total length of just under 150 pages, it is particularly well suited for full-time organisers and a broad readership outside of academic circles. Since it covers so much terrain and tackles many pressing questions head-on, it is, in many ways, a perfect primer on China. At the same time, it is packed with empirical details, extensive references, and insightful analyses that will be of interest to those with a strong working knowledge of the PRC.”

He goes on to argue that every socialist project has had to chart new territory in its own unique circumstances and explore ways of eking out an existence in a hostile, imperialist world intent on destroying it. Implicit in the book’s argument is the rejection of the idealist approach to the question of socialism, which consists in defining it in the abstract and then dismissing anything in the real world that does not live up to this speculative abstraction. Instead, Bennett and Martinez invite us to approach the issue of socialism from a dialectical materialist vantage point. This means recognising that it is a process that takes on specific forms in different material circumstances, and we, therefore need to analyse the complexities of practical reality rather than simply relying on theoretical definitions from the sidelines of history.

Outlining some of China’s achievements, as presented in the book, he writes that:

“Since many of these facts are undeniable and even admitted by the imperialist powers, there has been an attempt to attribute China’s meteoric rise to its supposed embrace of capitalism in the post-Mao era. Many analysts, including self-proclaimed Marxists, embrace a schematic and reductivist version of history that simply juxtaposes a socialist age under Mao to a capitalist epoch begun with Deng Xiaoping. One of the many strengths of this book is its dialectical and materialist approach to the history of the People’s Republic, which provides a fine-grained elucidation of the concrete realities of the PRC’s developmental strategy rather than falling prey to metaphysical ‘all or nothing’ assumptions.”

Echoing the conclusion of Deng Xiaoping’s November 1989 talk with Julius Nyerere, the founding president of Tanzania, Gabriel summates:

“As long as China remains on the socialist path, approximately one sixth of the world’s population will be living under socialism and striving – against great odds – to chart uncharted territory. As one of the longest lasting and largest socialist experiments on planet Earth, there is much to learn from it. This book is an indispensable guide to understanding the PRC and appreciating its impressive accomplishments in only seventy-five years of existence.”

Gabriel Rockhill is the Founding Director of the Critical Theory Workshop / Atelier de Théorie Critique and Professor of Philosophy at Villanova University, USA.

“People’s China at 75: The Flag Stays Red” can be purchased from the publishers in paperback and digital formats.

This review was originally published by Black Agenda Report. It has also been republished by Popular Resistance and Internationalist 360°. An abbreviated version was published by the Morning Star.

One of the most legendary scenes of revolutionary joy in the history of the world socialist movement is said to have occurred when Vladimir Lenin reportedly went out to dance in the snow in order to celebrate the fact that the recently minted Soviet Republic had outlasted the Paris Commune. The workers who had taken over the French capital in 1871 and launched a collective project of self-governance were able to hold out for seventy-two days before the ruling class trounced this experiment in a more egalitarian world. Karl Marx, writing on these events at the time, celebrated the unprecedented advances of the workers’ movement while lucidly identifying its principal limitation: it had not crushed the bourgeois state and founded a proletarian state capable of defending its interests. This is a lesson that Vladimir Lenin had taken to heart, and his reputed dance in the snow feted the practical success of a correct theoretical assessment.

The Soviet Union lasted for seventy-four years if one includes the five years of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1917-1922). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) recently outstripped it by celebrating its seventy-fifth birthday (1949-2024). Measured in years rather than days, the celebration organized in the Great Hall of the People was much more sober than Lenin’s purported frolic in the snow. It included a balanced appraisal of what has been accomplished thus far and what remains to be done. President Xi Jinping delivered a speech that stressed how the Communist Party of China (CPC) “has united and led the Chinese people of all ethnic groups in working tirelessly to bring about the two miracles of rapid economic growth and enduring social stability.”[1] Reactions in the imperial core, known for its histrionics regarding China’s imminent collapse, were markedly different. The title of one of the Associated Press’s articles directly contradicted Xi Jinping’s claim: “China marks 75 years of Communist Party rule as economic challenges and security threats linger.”[2]

Has the PRC undergone a miraculous and largely peaceful transformation in its seventy-five years of existence, or is it economically unstable and a threat to security? Given the centrality of the “China question” to political debates around the world, it is inevitably bound up with a number of other pressing issues. For instance, is the PRC’s extraordinary economic growth due to its particular form of socialism, or has it taken the capitalist road since the reform and opening up in 1978? For those who support the struggle for a more egalitarian and ecologically sustainable world, should the fact that China has become one of the longest lasting, as well as the largest, self-declared socialist countries be a cause for celebration and maybe even a gleeful dance in the snow à la Lenin? Or should it be met with trepidation, perhaps even stalwart condemnation, as some leading Western intellectuals have maintained?

People’s China at 75, a Praxis Press publication edited by Keith Bennett and Carlos Martinez, seeks to respond to these questions and others through rigorous materialist analysis and a coherent theoretical framing of the PRC’s place in world history. Comprised of eleven incisive analyses framed by a capacious introduction, the book serves as a useful guide to anyone interested in a crash course on China by some of the world’s leading experts on the question. Given its readability, with concise essays and a total length of just under 150 pages, it is particularly well suited for full-time organizers and a broad readership outside of academic circles. Since it covers so much terrain and tackles many pressing questions head-on, it is, in many ways, a perfect primer on China. At the same time, it is packed with empirical details, extensive references, and insightful analyses that will be of interest to those with a strong working knowledge of the PRC.

Bennett and Martinez are known to many for their indefatigable struggle against imperialist propaganda with their platform Friends of Socialist China, which has sought to build an understanding of, and support for, Chinese socialism. Their introduction lays out the importance of recognizing, when examining contemporary China, that there is “no ready-made blueprint or master plan” for socialism (vi). Every socialist project has had to chart new territory in its own unique circumstances and explore ways of eking out an existence in a hostile, imperialist world intent on destroying it. Implicit in their argument is the rejection of the idealist approach to the question of socialism, which consists in defining it in the abstract and then dismissing anything in the real world that does not live up to this speculative abstraction. Instead, Bennett and Martinez invite us to approach the issue of socialism from a dialectical materialist vantage point. This means recognizing that it is a process that takes on specific forms in different material circumstances, and we, therefore need to analyze the complexities of practical reality rather than simply relying on theoretical definitions from the sidelines of history. One of the things that this bottom-up approach reveals, on their account, is that there is “no great wall” between the Mao period and the reform and opening up under Deng Xiaoping (x). Far from being a neoliberal capitalist, the latter resolutely defended what he called the Four Cardinal Principles: “the dictatorship of the proletariat (generally referred to as the people’s democratic dictatorship in the conditions of China), the socialist road, the leadership of the Communist Party, and Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought” (xi).

This dialectical materialist understanding of contemporary Chinese history frames the book as a whole and undergirds its evaluative claims. Although it marshals a strong defense of the PRC against imperialist propaganda and those who believe it, it does not seek to paste over its mistakes and limitations. Authors point out, for instance, “the failure of the state to respond effectively in the years of famine from 1959 to 1962” (20) and, in post-Mao China, “the dizzying levels of income inequality, the persistence of unemployment and the intrusion of market relationships into basic public services” (36). They also highlight the fact that, in spite of its impressive contributions to developing an environmental civilization, the PRC’s ecological record has been “far from perfect” and it was “the world’s largest coal consumer” in 2023 (111 / 106). The rise of the People’s Republic has been an arduous struggle, and it has often had to make significant tactical compromises in order to advance its overall strategy. Any evaluation of it needs to be grounded in a balanced assessment, as well as a clear-eyed understanding of the concrete, material context. Kenny Coyle brings this to the fore in his contribution, which he punctuates with an insightful quote from Marx: “defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby” (53).

What is remarkable, however, is that despite setbacks, mistakes, tactical compromises, and incredible adversity, China has made truly awesome progress in its seventy-five years of existence. Having suffered a “century of humiliation” through extreme colonial underdevelopment prior to 1949, it has totally transformed itself under the rule of the CPC. As Martinez writes in his excellent concluding chapter:

Living standards have increased dramatically; extreme poverty has been eliminated; China has become a global leader in science and technology; it leads the way in addressing the climate crisis; Chinese society is highly stable; and the government enjoys an outstanding level of popularity and legitimacy (134).

The People’s Republic has become a moderately prosperous society in all respects, and it leads the world in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP). The average annual growth rate between 1978 and 2023 was an incredible 9.4 percent, which “exceeded that of almost all capitalist countries” (42). It must be remembered that this development has been accomplished within what amounts to the approximate lifespan of a single human being in a developed country (seventy-five years). China is thus at the very beginning of its ascent toward socialism. In this brief time, it has already nearly doubled the life expectancy of its 1.4 billion people, which now stands at seventy-eight years of age (see 28).

Since many of these facts are undeniable and even admitted by the imperialist powers, there has been an attempt to attribute China’s meteoric rise to its supposed embrace of capitalism in the post-Mao era. Many analysts, including self-proclaimed Marxists, embrace a schematic and reductivist version of history that simply juxtaposes a socialist age under Mao to a capitalist epoch begun with Deng Xiaoping. One of the many strengths of this book is its dialectical and materialist approach to the history of the People’s Republic, which provides a fine-grained elucidation of the concrete realities of the PRC’s developmental strategy rather than falling prey to metaphysical “all or nothing” assumptions. The reform and opening up, beginning in 1978, did not simply abandon socialism in favor of capitalism. It sought, through a gradual process based on practical experimentation and constant reassessment, to use capitalism in order to develop the productive forces, while maintaining Communist control of the state and the towering heights of the economy. This tactic was developed in a very specific context in which the Chinese were studying and learning from the mistakes of the Soviet Union, whose economy stagnated from the mid-1970s. It also became essential for fighting one the dominant forms of U.S.-led imperialism, namely neocolonialism. If an anticolonial revolution could be made through the use of arms and the seizure of the state, the control of banks and capital, as China has insisted on, were necessary in order to fend off the pernicious forces of neocolonialism.

Far from turning its back on Mao and the Marxist-Leninist tradition, the Deng administration made tactical decisions that had precedents in the Mao era. In fact, as Coyle points out, they can even be traced back to Lenin, who wrote in 1921:

Inasmuch as we are as yet unable to pass directly from small production to socialism, some capitalism is inevitable as the elemental product of small production and exchange; so that we must utilize capitalism (particularly by directing it into the channels of state capitalism) as the intermediary link between small production and socialism, as a means, a path, and a method of increasing the productive forces (56-57).

This is not without its risks, of course, but the Chinese state has set itself the task of using capitalism for people-centered development rather than being used by it for profit-centered expansion.

This is clear, for instance, in its complete rejection of colonialism and neocolonialism, which have been driving forces behind capitalist development. The People’s Republic is dedicated to peaceful coexistence, including with capitalist and imperialist states (see 143). It has not been involved in a significant military conflict since the 1970s, and it only has one military base outside of its mainland, which is for fighting piracy off the Horn of Africa. The primary goal of its foreign policy is to promote global peace and foster win-win development. According to Cheng Enfu and Chen Jian, the PRC “has always insisted on the equality of all countries, irrespective of their size, strength, and wealth, and has respected the sovereignty and territorial integrity of each country and its path to development and the social system that has been chosen by its people” (47).

This egalitarian, people-centered approach to foreign policy is also readily visible in its domestic politics. Pushing back forcefully against imperialist propaganda, the book foregrounds the important fact that China has implemented a “whole process People’s Democracy” that far outstrips the empty formalism of bourgeois democracies (43). As Cheng Enfu and Chen Jian explain, this means at least three things: (1) the people not only have the right to vote but also the right to broad and meaningful participation in governance; (2) there is a “systematic ‘full-chain democracy” that includes “the five major democratic processes of democratic election, democratic consultation, democratic decision-making, democratic management, and democratic supervision” (44); (3) “China has basically established the institutional, procedural, and standardized rules for the operation of power,” including a system of laws that, crucially, are practically implemented (45). As Jenny Clegg points out, China’s legal system has been marked by transformative democratic legislation. This includes “the Marriage Law of 1950 [that established]… equal rights for men and women” and the “arrangements for regional autonomy” that enshrined, in 1953, “equal rights for China’s 55 national minorities… legislating freedom to develop their own languages and to preserve or reform their traditions and religious beliefs” (15).

China’s people-centered development model, very much in line with the dialectical understanding of the relationship between humanity and nature, involves a growing dedication to fostering an “environmental civilization” in order to counter the catastrophic consequences of capitalist-driven ecocide. It is certainly true that the PRC was forced, by an imperialist world, to make tactical environmental sacrifices in order to develop the productive forces. However, in successfully arriving at incrementally higher stages of development, what has also become increasingly clear is the extent to which China’s strategic objective is to fully modernize society through ecologically sustainable development. As Efe Can Gürcan explains in his data-filled essay, the administration of Hu Jintao (2003-2013) put forth a “vision of a harmonious society [that] extended beyond social equality and justice to include balanced development across urban and rural areas, regions, socio-economic spheres, human-nature relations, and domestic and international contexts” (104). The PRC has since instigated a veritable ecological revolution whose scale is truly inspiring. Some of its impressive achievements include the following:

- “By 2009, China became the leading global investor in sustainable energy technology” (106).

- “By 2015, China had become the world’s largest producer of solar, wind, and hydroelectric power… In 2023, China installed more solar panels than the entire cumulative total in the United States” (106).

- “China is by far the leading country in installed renewable energy capacity” (106).

- “China leads the world in renewable energy consumption (including geothermal, wind, solar, biomass, and waste)” (106).

- “China ranks 38th among the world’s biggest per capita carbon emitters, with a significantly lower performance (8 tons of CO2) than the United States (14.9 tons of CO2)” (107).

- “By 2015, China had achieved the highest net increase in forest coverage of any country” (108).

- “China’s cities have also joined the ranks of those with the strongest sewage treatment capacity in the world. In addition, China has the most electric vehicles, bikes, and efficient public transportation” (108).

- “By 2015, China had developed or planned 284 of the world’s 658 major eco-cities” (108-109).

As People’s China at 75 lays out in detail, all of these accomplishments are due to the fact that—as the book’s subtitle explains—The Flag Stays Red. It is Marxist theory and socialist practice that have been the driving forces behind the PRC’s remarkable socio-economic rise, people-centered development, and emergent environmental civilization. Bennett and Martinez’s book brings this clearly into focus, and its authors marshal their extensive expertise to provide copious empirical data to support the volume’s overall argument. As a theoretical rejoinder to Lenin’s frolic in the snow, feting seventy-five years of the PRC rather than seventy-three days of the Soviet Republic, it should be a cause for much joy among those beleaguered by endless imperialist wars, rising fascism, non-stop capitalist social murder, and unrelenting ecocide. As long as China remains on the socialist path, approximately one sixth of the world’s population will be living under socialism and striving—against great odds—to chart uncharted territory. As one of the longest lasting and largest socialist experiments on planet Earth, there is much to learn from it. This book is an indispensable guide to understanding the PRC and appreciating its impressive accomplishments in only seventy-five years of existence.

[1] “A Reception to Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China Grandly Held in Beijing: Xi Jinping Delivers an Important Speech,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The People’s Republic of China (September 30, 2024), https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/xw/zyxw/202410/t20241001_11502067.html .

[2] “China Marks 75 Years of Communist Party Rule as Economic Challenges and Security Threats Linger,” Associated Press (October 2, 2024), https://apnews.com/article/china-communist-party-foundation-day-russia-south-china-sea-5f140a2c8db38029ea0c0f2769e9f619#.