We’re pleased to republish this article from Global Times, shining a light on a powerful and inspiring episode in the history of China-Africa solidarity.

It was the beginning of the year 1970. News came that Wang Xingguo was about to work on a railway project in Africa. His wife Zhang Yunhua was very reluctant to let him go: Africa is so far away and their sons are still too little — the elder one is three years old and the younger one is only two. Wang tried to explain: He is a cadre, a CPC member; when duty calls, he must be the first to sign up. In October that year, Wang, together with over 1,000 co-workers, got on board the ocean liner Jianhua in Guangzhou and left for Tanzania.

The Civil Affairs Bureau of Taixing City still keeps a copy of an article written by Wang Xingguo in 1971. He began the article with two quotes from Chairman Mao Zedong. One goes, “I am for the slogan ‘fear neither hardship nor death.'” and the other, “China ought to make a greater contribution to humanity.” For Wang, the first quote reflects his attitude; the second explains why he decides to go to Africa.

In Tanzania, Wang Xingguo took part in the construction of the Irangi Number 2 Tunnel. Undeterred by the risks of flood and possible collapse of the soil structure, he was working with frontline workers on the foundation pit of the tunnel portal when the structure suddenly came down. He was buried underneath right away and died from lethal injury despite the best efforts of doctors. For the cause of world revolution, Wang made the ultimate sacrifice. He was only 35 years old.

The Chambeshi River Bridge was the largest railway bridge in Zambia, spanning a length of 267 meters. The river below was 5.6 meters deep. To survey the riverbed, Li Jinyu and three of his colleagues from the Chinese engineer team, jumped into the river without any diving or underwater lighting equipment but only a rope tied around their waists. Repeated exposure to freezing waters caused Takayasu arteritis and permanent loss of sensation in both of Li’s legs. He had to be amputated and was paralyzed for life. Carpenter Cai Jinlong was diagnosed at a late stage of stomach cancer, and threw up everything he tried to eat. Despite the biting pain, he insisted on working on the scaffold and refused to leave his post. When he was finally sent back to his wife in China, Cai was thinned to the bone.

Chama, a 64-year-old railway engineer, has worked on the Tanzania-Zambia Railway (Tazara) for more than four decades, and witnessed almost the entire process of the railway’s operation. Chama describes himself as a student of the Chinese master workers. He still remembers his first Chinese teacher Mr. Liu, from whom he benefited immensely both in work style and expertise. Chama started learning from Mr. Liu in 1978 on how to make railway parts. Every time Chama finished a product, Mr. Liu would examine it carefully and make sure it meets all quality standards before allowing him to move on to the next one. Chama believes that he has remained competent for the job over the years thanks to a strict tutor like Mr. Liu. Though the full name of Mr. Liu can no longer be figured out, one can tell from Chama’s recount his deep respect for his Chinese teacher.

The Tazara Railway is 1,860.5 kilometers long, linking the former Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam in the east with the town of Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia’s Central Province in the west. It runs through four regions in Tanzania and two provinces in Zambia, and crosses the Great Rift Valley, known as the scar of the Earth, as well as harsh terrains with extreme height variance — from rugged mountains, precipitous valleys, deep canyons, to rivers, lakes, forests, savannas and huge swamps. After visiting the railway, a Western engineer exclaimed that only the people who had built the Great Wall could have completed such a high-quality railway.

Both Tanzania and Zambia gained independence in the 1960s amid a wave of national liberation in Africa. However, economic development in both countries faced enormous difficulties due to external blockade. Their leaders appealed to a number of countries for assistance in building a railway linking the two nations. After conducting their survey, Western countries declared the railway as without commercial sense.

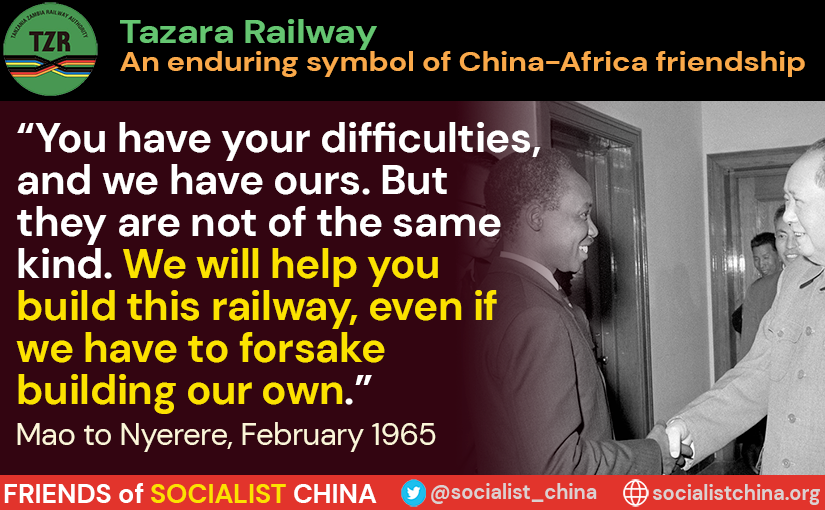

In February 1965, then Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere visited China. During their meeting, Chairman Mao Zedong said to him, “You have your difficulties, and we have ours. But they are not of the same kind. We will help you build this railway, even if we have to forsake building our own.”

President Nyerere, one of the initiators of Tazara, had this to say about the railway: In the past, construction of railways by foreigners in Africa was for the purpose of plundering Africa’s wealth. The Chinese did it for a totally different purpose; they built it to help us grow our national economy. Kenneth Kaunda, Zambia’s founding President and leader of the independence movement in the southern part of Africa, described that part of history emotionally, “The history of Tazara is that former President Nyerere of Tanzania and I, myself went to the West and told them we need this railway between Tanzania and Zambia… The West rejected that proposal. They said… don’t think of this. President Nyerere and I then went to see Chairman Mao, and the prime minister (Zhou Enlai). We talked and put it to them, and they readily agreed, ‘we’ll go together to build that railway,’ this came. They came as brothers and sisters, as friends, as comrades with common struggle… So you can see, the friendship is genuine. When others thought it was not necessary… we built it. What more friendship do you want to see more than that?”

On September 5, 1967, the governments of China, Tanzania and Zambia signed an agreement in Beijing on building the Tazara Railway. When many countries and international organizations all declined to help, China provided an interest-free loan of 988 million yuan with no conditions attached. In addition, China sent nearly 1 million tons of equipment and materials, as well as experts for the construction, management and maintenance of the railway and the training of local technicians. After the construction officially began, China sent a total of 56,000 engineers and workers to the project, with as many as 16,000 Chinese workers on site at its peak. The work involved the construction of 320 bridges, 22 tunnels and 93 stations;however, this Uhuru Railway (Uhuru being the Swahili word for freedom) was completed in just five years and eight months — all construction and installation efforts finished in 1976. A West German correspondent wrote about the China speed in a press piece: The Chinese and Americans are in a bitter wrestling in Eastern Africa. Today, one thing is for sure — The Chinese undoubtedly has the upper hand. The Chinese railway project is a year and half ahead of schedule, whereas the Americans are months behind theirs.

Today, across the vast savanna between Tanzania and Zambia, the Tazara Railway, a symbol of true friendship and sincere assistance of the Chinese people toward the people of Africa, is still running day and night. More than 60 Chinese workers rest forever on this land far away from home; the youngest of them, Jin Chengwei, was not yet 22. In recent years, another two China-assisted rail lines — the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway and the Mombasa-Nairobi Railway — have both been put into operation. These rail projects have played an important role in promoting economic and social development of regional countries and faster industrialization in Africa.

Martyrs fall and are laid to rest in a foreign land, but their spirit lives on and continues to inspire people today. Generations of Chinese aid workers have made selfless contributions and demonstrated the great spirit of internationalism, honoring China’s commitment to African brothers with life and blood. They are the heroes who have forged the immortal friendship between China and Africa .