The following is the main body of a speech delivered by Friends of Socialist China Co-Editor Keith Bennett at a dinner held in West London on Sunday June 27 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China.

The event was organised and hosted by Third World Solidarity and its Chair, Mushtaq Lasharie, a distinguished political and social activist in Pakistan and Britain. It was attended by a number of prominent members of the Pakistani community in Britain and veteran friends of China from various walks of life.

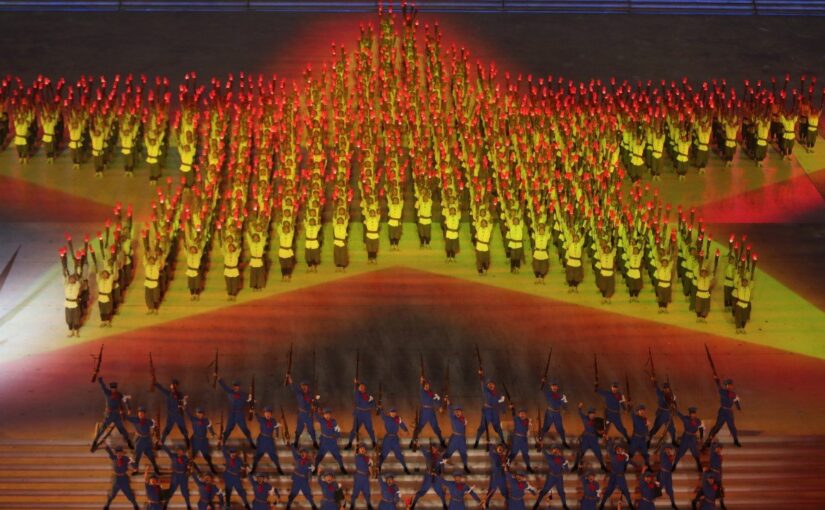

This coming Thursday, July 1st, marks the Communist Party of China’s centenary.

Whatever your opinions, this is an important occasion. This party has a membership of some 92 million people. Considerably greater than the entire population of the UK. It leads a country of 1.4 billion people. That country is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and is the world’s second largest economy. By some measures it is already the largest economy. Whether it be international financial crisis, pandemic, climate change or regional hotspots, the management and solution of global problems cannot today be considered separate from the role of China.

To take this snapshot of where China is today is to reflect on the extraordinary journey this country has undergone since some 13 people, representing a little over 50 members, met in Shanghai, a city then under the effective control of foreign imperialists, in conditions of great secrecy and danger, to found the communist party.

With a history of some 5,000 years, China is the world’s longest, continuous and recorded civilisation. Its origins are roughly contemporaneous with the Indus Valley civilisation centred on today’s Sindh province in Pakistan. Many of the world’s great inventions, such as printing, the compass, gunpowder (which the Chinese used for fireworks not for military purposes) and countless others originated from China. If one looks at the last twenty centuries of human history, China was the largest economy in the world for about 17 of them. The other biggest economy was that of an obviously pre-partitioned India. Together these civilisations traded with their counterparts as far as Europe along the ancient silk routes that in considerable measure prefigure today’s Belt and Road Initiative.

However, history does not develop in a straight line but according to a process of uneven development.

Western powers, in time followed by Japan, embarked on a process of colonial expansion, dividing the wealth and riches of the world amongst themselves and fuelling their industrial revolutions.

China, in turn, under the rule of feudal dynasties, fell into a period of complacency, stagnation and decline. It was ripe for picking by greedy, rapacious imperialist powers.

Whilst never completely colonised China became a semi-colonial, semi-feudal country. Bits of territory were snatched away. Unequal treaties were imposed. Imperialist powers enjoyed extra territorial privileges in major cities and elsewhere. The mass of Chinese people endured unimaginable misery.

Perhaps most criminally of all, British capitalists, organised, for example in the East India Company, forced opium onto the Chinese market, leading to terrible problems of addiction for the Chinese and enormous profits for the British.

When a patriotic Chinese official, Lin Zezu, attempted to stamp out this trade in death the British response was war. In the name of ‘free trade’ of course. Two opium wars resulted in bitter defeats for China, not least the loss of Hong Kong. Those in the Conservative Party, and indeed the Labour Party, who continue to speak of Britain’s supposed ‘responsibilities’ towards the people of Hong Kong should do more to reflect on, and repent for, that shameful history.

For the Chinese people, with their long history of civilisation, this period is known as the ‘century of humiliation’. Chinese patriots and enlightened people searched for a way out – through huge peasant revolts, reform movements, learning from the West and from Japan, and finally a democratic revolution led by an outstanding figure, Dr. Sun Yat Sen. But all these ended in failure and disappointment. The country remained in ruins. The people remained impoverished.

World War I and its immediate aftermath offered a further brief ray of hope. China had entered the war on the side of the eventually victorious allies. Organised as the Chinese Labour Corps (white imperialists did not really trust Chinese working people with guns), tens of thousands of Chinese made a contribution to the allied victory, enduring huge casualties, terrible conditions and brutal discipline that might be likened to slavery.

When the victorious powers gathered at Versailles, Chinese people expected their sacrifice to be rewarded. They were given some cause. US President Woodrow Wilson talked big about the ‘right of nations to self-determination’. However, it was to become clear that in the mouth of Wilson, who was actually an associate of the notorious Ku Klux Klan, self-determination was for white people only – and not even all of them, as the Irish and some others could attest.

When, in 1919, the German concession of Shandong province, rather than being returned to China, was handed to Japan, the people of China, with youth and students, a number of them influenced by Marxism, in the foreground rose in a great mass struggle known as the May 4th Movement.

It was at this moment that the idea of looking to and following the West died among enlightened Chinese. As Mao Zedong, who was to go on to lead the Chinese revolution and found the People’s Republic of China, memorably put it, people could not understand why the master was always beating the student.

However, another external event, itself impelled in no small measure by the impact of world war, was also to now make its mark in China. To the north, the Russian Revolution had occurred in 1917, which was to lead to the birth of the Soviet Union and the building of the world’s first socialist state. And in stark contrast to the actions of the victorious powers at Versailles, among the very first acts of the new Soviet government in foreign affairs was to reject and repudiate the unequal treaties that the previous Tsarist regime had imposed on China.

This had an electric impact on a China that was already in ferment. And it was inspired by the Russian Revolution, and with the assistance of the Communist International (also known as the Comintern), that had been formed in Moscow, that the Communist Party of China was, as I’ve already mentioned, formed by just a handful of people.

From such tiny and modest beginnings the Chinese Communist Party grew rapidly, especially among the young and extremely militant Chinese working class. The other key factor impelling its growth was the formation, with the advice and assistance of the Comintern, of a united front with the Guomindang, the nationalist party formed by Dr Sun Yat Sen, who had led the 1911 revolution that had overthrown the Qing dynasty and formed a republic.

Also influenced by the October Revolution, Dr Sun had moved to the left and now advocated alliance with Soviet Russia, cooperation with the Communist Party and support for the workers and peasants.

However, Dr Sun passed away in 1925 and his successor as leader of the Guomindang, Chiang Kai Shek, was a very different person – far more opposed to socialism and the working people than he was to the warlords, who then still controlled much of China, and imperialism.

In 1927, in what became known as the Shanghai Massacre, Chiang unleashed brutal repression on the communists and anyone even remotely suspected of supporting them. Many thousands were killed. The party’s survival hung by a thread, its survivors forced to either flee or go deep underground.

It was at this point, when the party had hit rock bottom, that Mao began to properly formulate what I consider his greatest contribution to the science of the liberation of oppressed people, not only in China, but in many other countries, too. From a peasant background himself, the young Mao had already distinguished himself, for example in the very first article in his Selected Works, the Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society, by the importance he attached to the peasantry, as the largest class in Chinese society, and in his grasp of its enormous revolutionary potential.

From here begins the transition from tragedy to triumph, with the formulation of a set of strategies and tactics that embraced the building of stable revolutionary base areas, the waging of protracted people’s war in the primary form of guerrilla war, and surrounding the cities from the countryside so as to ultimately seize nationwide political power. This was something completely new in Marxism, which had always hitherto stressed the central role of an urban industrial working class.

Another key turning point was World War II. Actually you can say that World War II began not in Europe but in Asia, with Japan’s invasion of northeast China in 1931 and then the rest of the country in 1937. Despite the rivers of blood between Chiang Kai Shek and the communists, Mao and his comrades like Zhou Enlai saw that it was necessary for all the forces of the nation to join together to fight the Japanese aggression. Very reluctantly – in fact he had to be kidnapped and held prisoner by two of his own generals to secure his compliance – Chiang agreed to the formation of a second united front with the communists.

China’s resistance, which saw tens of millions of casualties, made a major contribution to the allied victory over fascism. In particular, by tying down millions of Japanese forces, it ensured that the Soviet Union never had to fight on two fronts at once.

In the immediate post-war period some efforts were made to continue the united front and to form a democratic coalition government, but these foundered as a result of both Chiang’s deep-seated anti-communism and the shift to the right in the United States with the death of Roosevelt and the onset of the Cold War.

Thus, from 1946, a revolutionary civil war ensued, culminating in a communist victory in 1949. I would cite three main reasons for this victory:

- The role played by the communists in the anti-Japanese resistance.

- The hopeless corruption and venality of the Chiang regime, which led to problems like hyper-inflation and alienated not only working people but also intellectuals, national and patriotic capitalists and other sections of the population

- Significant levels of support from the USSR.

On October 1st 1949, Chairman Mao stood on the rostrum of Tiananmen Square, in the heart of Beijing, and proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China with the words: “The Chinese people have stood up.”

The Chinese people may have stood up but they had reclaimed a broken nation. Poverty, hunger, disease and illiteracy were rampant. Life expectancy was pitifully low. China was practically the poorest country in the world.

In their way, the years from 1949 have been as momentous and tumultuous for China as the years from 1921-1949.

Scarcely one year later China was again at war as the United States threatened to extend their vicious war in Korea into an invasion of China. At home a massive programme of land reform uprooted feudalism and landlordism, while a state-directed mixed economy, combined with significant aid from the Soviet Union, started to lay the foundations of industrialisation and modernisation.

But it was not all plain sailing. A tendency towards increased and excessive radicalisation combined with a damaging estrangement from the Soviet Union led to a succession of mass movements, culminating in the Cultural Revolution, which broke out in 1966 and lasted in one shape or another until Mao’s death in 1976. The Cultural Revolution, whatever its original intentions, ruined lives, inflicted deep wounds on society and retarded economic development. Nevertheless important achievements were still scored in this period, including China’s successful development of the H bomb in 1967, which obviously enhanced national security in a critical period, and the launch of its first satellite, appropriately playing the revolutionary song, The East is Red, in 1970.

Whatever the mistakes China made in this or any other period it successfully solved the basic problems of providing food, clothing, shelter, education and health care, the most essential and fundamental human rights, to nearly a quarter of the world’s population. This would have been impossible without the revolution and is something that has singularly eluded other large and broadly similar developing countries such as India, whose social and economic position, whilst not good, was better than China’s at the end of the 1940s.

Following Mao’s death the country’s new leaders, with Deng Xiaoping as their foremost representative, summed things up and embarked on a programme that they called ‘reform and opening up’.

The decades that have followed have seen nothing less than the most remarkable economic transformation in human history. China has lifted nearly a billion people out of poverty – constituting the absolute majority of global poverty reduction. From a negligible actor in the global economy, China has become, as I stated at the start of my talk, the world’s second largest economy. China’s space programme has landed on Mars and become the first country to land on the dark side of the moon.

These are among the many, countless achievements of the Chinese Communist Party and although the things I have just mentioned have occurred in the reform period that began in late 1978 they cannot be separated from the revolutionary struggles waged from 1921-49 and from the foundations of a new society built between 1949-78. They are achievements of 100 years.

Not least, as China constitutes around 22% of humanity, such achievements and transformation cannot but also have a profound impact on the world scale.

China has become an alternative source of trade and investment for countries around the world, the great mass of developing countries in particular. It is China’s great economic strength that has allowed it to launch the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as an unprecedented programme of investment in infrastructure and connectivity, with, as I mentioned earlier, its contemporary echoes of the ancient silk routes.

In the front of the BRI is, of course, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship project that reflects the very special friendship between Pakistan and China, whose 70 years of diplomatic relations was marked by both countries less than two months ago. In 2017, I was fortunate to visit Islamabad, Karachi, Gwadar, Quetta, Rawalpindi and Karot and to see how CPEC is already transforming the lives of people in Pakistan. And the closeness between the people of the two countries could be seen not only in Pakistani and Chinese workers working side by side, but also by seeing Chinese people wearing shalwar kameez and speaking fluent Urdu.

The fact that China is increasingly able to offer an alternative to the whole world is, in my view, a key factor in the dramatic ramping up of hostility to China that we have increasingly seen on the part of the major western powers.

The United States and other major western powers had two key expectations when they engaged with China in the reform period:

- That China would remain a cheap labour global factory and assembly point rather than advancing to the front ranks of science and technology, innovation, research and development.

- That as China became increasingly integrated into the global economy and society, it would give up socialism, give up the leadership of the communist party and adopt some variant of the political and economic system prevalent in the West.

It didn’t happen. In fact China’s present leader, Xi Jinping, is clearly totally determined to make China both more developed and more socialist.

Hence we see a dangerous new Cold War against China. This Cold War, like its predecessor, is against the interests of humanity. Global challenges that threaten every person on earth, such as the current pandemic and the looming threat of climate change, cannot be tackled without the active and constructive input of China. Without China and its growing strength, developing countries such as Pakistan would have very few options. They would to a great extent be at the mercy of the colonial and imperialist powers and their international financial institutions.

I’d like to ask you to keep this background and this big picture in mind when you come up against the huge lies that are currently being told about Xinjiang. I’d like to ask you to remember and reflect on what the western powers and their key allies have done to the Muslim world over this last period. How many innocent Muslims have they massacred, or starved with sanctions, in Iraq, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan (with their drone strikes), Iran, Lebanon, Palestine, Yemen, Somalia, Kashmir, and so on? And yet the rulers of the United States and Britain, the very people responsible for these atrocities and crimes against humanity, want to pose as the guardian angels of Muslims in China? I think this strains credibility. No wonder that not a single government of a Muslim-majority nation, despite some undoubtedly serious pressure, has taken the West’s side against China on this matter. In fact they nearly all, if not all, enjoy a great and mutually beneficial friendship with China.

In the course of its history, of course the Chinese Communist Party has made mistakes. Even a minor human activity cannot be free from error, leave alone one as enormous as this. But the achievements of the CPC are unprecedented and greater than those of any other political party in history without exception. They have changed the face of China and the world and this centenary is one worth celebrating.