A high-level delegation from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, headed by its Chair, Dr. Heinz Bierbaum, visited China in March. The foundation is closely associated with Germany’s Die Linke (Left Party).

The following article, which we reproduce from the foundation’s website, details the background to the delegation, reports its visits and meetings in Beijing, Zhejiang and Shanghai, and outlines the key themes for its future work with China. Giving an overall context, the article notes:

“Over the span of two generations, the People’s Republic of China has gone from one of the poorest countries in the world to its second-largest economy and a rising global power, and did so while maintaining its own, distinct developmental model. Its state-directed market economy has lifted over 800 million people out of poverty, and garnered the attention of other developing countries looking to extract themselves from the middle-income trap.”

It adds that the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation is working to reinvigorate ties between China and progressive parties and movements in Germany, in the spirit of fostering a global debate on the nature of socialism in the twenty-first century.

Moving forward, the work of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Beijing Office will focus on exchanges between European and Chinese Marxists, translating Chinese debates into Western contexts and vice-versa.

Dr. Jan Turowski, office director since 2017, argues that different historical contexts must always be taken into account when evaluating debates on Marxism and socialism:

“In China, and particularly in the Communist Party, socialism is treated less as a state of affairs than a goal-oriented strategic process… As a theoretical debate in constant interplay with practical developments, conflicts of interest, and policy demands, it changes, experiments, conforms, and yet continues to structure the political process, giving it direction over the longer term… In contrast, the debate in the West as to whether China is socialist or not often focuses — rather unproductively — on a state of affairs and set of binary categories: either a society is socialist or it is not. Many Western leftists discuss China’s contradictions as good or bad, right or wrong, rather than confronting them as an integral part of the socialist experiment. Nevertheless, bringing Chinese and Western debates on socialism together in an open-minded and interested way, without denying the many differences, might well spark some creative ideas.”

The observation is as banal as it is true: China’s economic and geopolitical rise over the past four decades has transformed both the country and the world around it, and will continue to do so for decades to come. Over the span of two generations, the People’s Republic of China has gone from one of the poorest countries in the world to its second-largest economy and a rising global power, and did so while maintaining its own, distinct developmental model. Its state-directed market economy has lifted over 800 million people out of poverty, and garnered the attention of other developing countries looking to extract themselves from the middle-income trap.

It was thus only natural for the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation to begin supporting projects in China in 2002, and open one of its first international offices there in 2008. Since then, our Beijing branch has grown from a modest outpost to a fully-fledged regional office, organizing high-level exchanges and joint conferences and publications with a number of universities, research institutions, and even the Communist Party of China. Against a backdrop of growing geopolitical tensions, the foundation’s work seeks to maintain and expand corridors for debate and exchange, and learn from each other’s experiences in the interest of mutual understanding. The many differences between China, Germany, and Europe notwithstanding, we are convinced that only through dialogue can conflicts be resolved in a constructive manner.

As the COVID pandemic draws to a close and travel restrictions ease, the office has intensified its activity by hosting several international delegations and organizing a series of seminars and workshops in China and Germany. Together with the launch of a new bilingual website, the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation is working to reinvigorate ties between China and progressive parties and movements in Germany, in the spirit of fostering a global debate on the nature of socialism in the twenty-first century. Chinese scholars often emphasize that their experience is unique and cannot be seen as a blueprint for movements and parties in other parts of the world. Nevertheless, any discussion of socialism’s prospects today cannot afford to ignore the experience of 1.4 billion people living under a system that describes itself as “socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

Friends from Afar

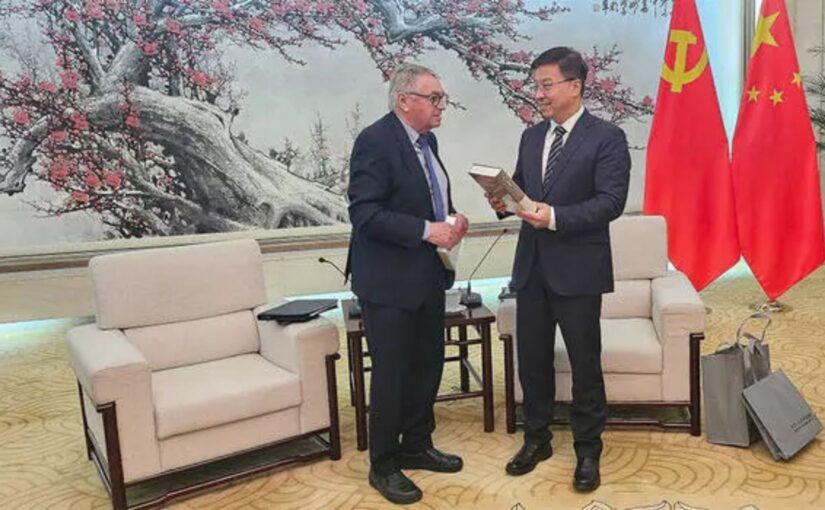

A recent sign of the office’s renewed activity was a high-level delegation to China in late March, hosted by the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) and led by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s chair, Dr. Heinz Bierbaum. Together with representatives from the foundation’s Executive and Academic Advisory Board, Bierbaum visited Beijing, Hangzhou, and Shanghai, and met with representatives of municipal administrations, cultural institutions, and the Communist Party.

The delegation began its trip with a visit to the Central Party School in Beijing, where Vice President Li Yi discussed China’s socialist modernization with participants and emphasized the need for mutual cooperation in international relations. Later in the day, delegates were received by CPAFFC President Yang Wanming, who emphasized the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s longstanding role in strengthening person-to-person exchanges between China and Germany, and expressed optimism that relations between the two countries would continue to develop positively. Further meetings with representatives of the International Department of the Central Committee and the National People’s Congress underlined the depth of cooperation the foundation has developed in China over the past two decades.

The country’s high-speed rail network has helped to transform China’s transportation system, and demonstrates what kind of green infrastructural development is possible under the right conditions.

After taking in the sights of Beijing, the delegation travelled south to Hangzhou, capital of the eastern coastal province Zhejiang. Here, participants visited the nearby model village of Xiaogucheng, where the local Party leadership has instituted a number of effective anti-poverty strategies and pioneered new structures of community governance. Hangzhou has also broken ground in its attempts to integrate high-tech development with environmentally sustainable urban planning, as the delegation learned in Dream Town, a major tech hub along the city’s historic waterfront that seeks to integrate, rather than replace, the existing ecological and urban space.

The delegation’s visit concluded in Shanghai, China’s largest and wealthiest city, where participants met with Chen Jing, President of the Shanghai People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, and learned about the city’s unprecedented growth within the framework of the state-led market economy. The Shanghai Master Plan, which runs from 2017 to 2035, seeks to turn Shanghai into a “modern socialist international metropolis” seamlessly integrating life, work, and the surrounding environment. It stands as an exemplary case of China’s approach to development, whereby the fundamental parameters of economic growth are laid out in a series of five-year plans, leaving ample room for experimentation and creativity at the local and regional levels.

Perhaps most remarkable for delegation participants was the substantial progress the People’s Republic has made in terms of what in China is referred to as “ecological civilization”. Electric vehicles were to be seen in every city the delegation visited, marked by their silent engines and green license plates that set them apart from the rest of the fleet. Indeed, in Shanghai, over half of new vehicle registrations are electric. The country’s high-speed rail network, which consists of 45,000 kilometres of track and encompasses two-thirds of all high-speed rail in the world, has helped to transform China’s transportation system, and demonstrates what kind of green infrastructural development is possible under the right conditions. Summing up his impressions, Dr. Bierbaum remarked that he was “deeply impressed by the level of economic and technical development achieved, above all by the fact that a high degree of qualitative and, in particular, ecological aspects have been taken into account.”

Expanding the Conversation

Moving forward, the work of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Beijing Office will focus on exchanges between European and Chinese Marxists, translating Chinese debates into Western contexts and vice-versa.

Dr. Jan Turowski, office director since 2017, argues that different historical contexts must always be taken into account when evaluating debates on Marxism and socialism:

In China, and particularly in the Communist Party, socialism is treated less as a state of affairs than a goal-oriented strategic process. The Chinese socialism debate is fundamentally a background melody to the practical business of politics, shaped by the various socioeconomic challenges and constraints of everyday policymaking. As a theoretical debate in constant interplay with practical developments, conflicts of interest, and policy demands, it changes, experiments, conforms, and yet continues to structure the political process, giving it direction over the longer term.

Not least, socialism provides Chinese policymakers with a normative albeit abstract set of goals and a complex catalogue of concepts and historical references. In contrast, the debate in the West as to whether China is socialist or not often focuses — rather unproductively — on a state of affairs and set of binary categories: either a society is socialist or it is not. Many Western leftists discuss China’s contradictions as good or bad, right or wrong, rather than confronting them as an integral part of the socialist experiment. Nevertheless, bringing Chinese and Western debates on socialism together in an open-minded and interested way, without denying the many differences, might well spark some creative ideas.

For the last two years, Turowski has edited a series of volumes together with Chinese colleagues, collecting contributions from Chinese Marxist debates and making them accessible to a German-speaking audience. The first, co-edited with Yang Ping of Wenhau Zongheng, focused on translations of domestic debates on socialism with Chinese characteristics. Rather than talking about Chinese socialism, the series seeks to stimulate engagement with it. How do Chinese politicians and scholars theorize Chinese socialism? Do binary oppositions between market and plan, or democracy and authoritarianism really do justice to China’s reality, or are more nuanced conceptions needed? What criticisms do Chinese thinkers have of their own system, and what do they defend?

The second volume, co-edited with Meng Jie of Fudan University’s Institute of Marxism, adopts a similar approach in seeking to explain how China’s market socialism functions and how it is understood within China itself. By collecting a number of contributions from across the Chinese academy, the volume conveys points of convergence and controversy and lays out, for foreign readers, the general parameters of discussion in China about the Chinese model. Upcoming volumes will address the relationship between Chinese and Western understandings of modernization and the potential implications of China’s rise for international socialism.

At a time when the world’s largest countries should be working together to tackle challenges like climate change, a new ideology of division has set in that threatens to hold back progress on both sides.

The office’s new website seeks to play the same role for an English-language audience by regularly publishing translations from the aforementioned Wenhau Zongheng, a leading journal of theory and social science in China. Its ongoing translation series, “Debate Unblocked”, publishes highlights from recent Wenhau Zongheng issues in an effort to literally “unblock” global debates on China’s contribution to international socialism by making source material accessible to non-Chinese audiences. The office also publishes translations of Chinese research papers and periodically conducts interviews with Chinese intellectuals and policy experts as further resources for international readers to inform themselves about China’s socialist model.

These publications, together with the “China Basics” series, which unpacks dozens of opaque-sounding Chinese terms for foreign ears, are conducted in the interests of making the Chinese experience more accessible to the international Left. Visitors may not agree with everything they read, but that is the point — opening up the conversation and dispelling preconceptions.

Reflecting on the Western reception of China’s domestic political discourse, Turowski noted:

China discusses about itself with itself, and this Chinese China discourse must be taken seriously in terms of its own logic and historical conditionality. Chinese voices have their say, discussing the country with and against each other in a differentiated and complex context of political questions and problems. Taking such a discourse seriously also means being confronted with positions and concepts that are rather alien, sometimes uncomfortable. This strangeness or discomfort does not have to be accepted uncritically. But in order to understand China, it is necessary to read it with its own terms and concepts.

Within China itself, the office will continue to facilitate international debate throughout 2024 and beyond. This year, the office will extend its close cooperation with the China Research Group on Socialist Eco-civilization (CRGSE), which it founded together with the Institute for Marxism Research at Peking University in 2017 and is becoming increasingly influential in the Chinese debate. The two will collaborate on symposia and conferences on various policymaking aspects and the strategic question of social-ecological transformation. The office will also hold a joint workshop with the Chunqiu Institute for Development and Strategic Studies on security and geopolitics in East Asia, as well as a joint workshop with the Institute for Party History and Literary Research entitled “Modernization and Political Organizations”, discussing how social and technological changes affect parties and organizations and how these can be productively addressed.

Tackling Global Problems Together

In the days after the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s delegation returned to Berlin, US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen also visited China, where she issued sharp criticisms of its export sector, accusing the Chinese of flooding Western markets with “cheap goods” and overwhelming Western manufacturers. These sorts of comments reflect growing animosity towards China on the part of the US and its European allies at a time of renewed geopolitical tension and, tragically, the outbreak of devastating wars in Ukraine and Gaza — along with many others that too often go overlooked. At a time when the world’s largest countries should be working together to tackle challenges like climate change, a new ideology of division has set in that threatens to hold back progress on both sides.

The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s influence on geopolitics is modest, to say the least, but both its office in Beijing along with its dozens of offices around the world are determined to contribute to a world in which mutual security is built on a foundation of peace and international relations are guided by cooperation, rather than rivalry and unbridled competition. By translating publications and facilitating person-to-person dialogues between China and the international Left, we hope to deepen understanding of China’s remarkable rise and, at the same time, explore what insights China can take from experiences in the rest of the world. The challenges our societies face are global — by learning from each other, we can tackle them together.