The following article by Sara Flounders, based on a talk given at our event Peace delegates report back from China: Building solidarity and opposing the New Cold War, calls for a joined-up anti-imperialism, positing that “the best way to oppose the new Cold War with China is to be the most militant opponent of every US war.”

Sara observes that the events of 7 October 2023 “opened a new chapter in the worldwide class war”. US imperialism is backing Israel to the hilt, desperate to protect its interests in the region – part of defending and expanding US global hegemony. “That means Palestine fights for all of us”, and those that oppose the US-led program to encircle and contain China should also stand with the people of Palestine.

Further, we should be standing firmly against the US’s unilateral sanctions, which are being used to undermine and destabilise a total of 40 countries currently.

The US and its allies are also engaged in a proxy war against Russia in Ukraine. The over-arching strategy is to “impose regime change on Russia, which would be a key step to their next move — against China.”

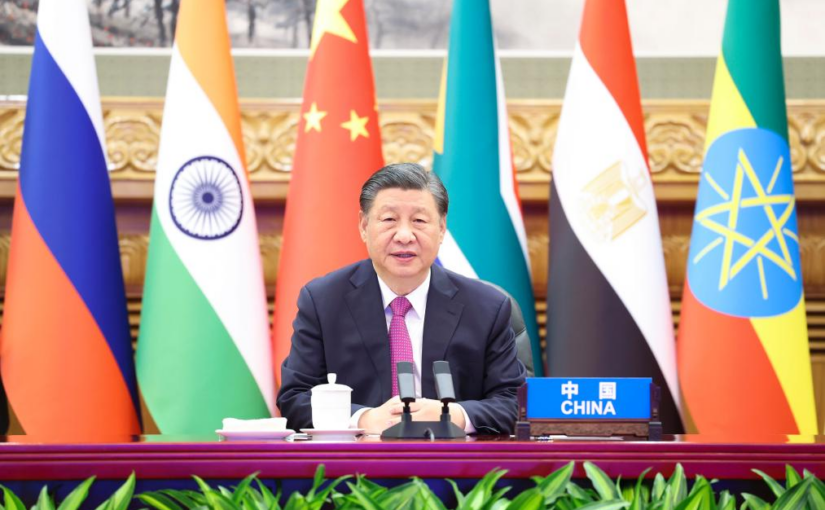

The basic dynamic in geopolitics today is the contest between a moribund imperialism and a rising multipolarity. As Sara writes, “China’s very existence as a prosperous, developing country confirms that humanity has another choice. The developing world, the Global South, looks to China — not to U.S. imperialism. That is a threat to imperialism.”

Sara concludes by calling on our movement to unite behind the slogans: “Hands off China! Full solidarity with Palestine!”

This article appeared first in Workers World.

With U.S. wars coming thick and fast, the best way to oppose the new Cold War with China is to be the most militant opponent of every U.S. war.

If Israel succeeds in crushing Palestinian resistance, based on U.S. financial, political and military support, then U.S. imperialism is stronger on a world scale. That means Palestine fights for all of us. Palestine’s resistance has ignited a global resistance.

Before October 7, Israel, after 75 years of U.S. backing, seemed all powerful. Now the Israeli military has been frustrated at every turn by the indomitable spirit of Palestinian resistance. The Israelis face ambushes without end.

There is a sea change in the U.S. working class. For the first time, a majority of the population supports Palestine. There is sharp opposition to U.S. policy, shown by mass marches, shutdowns, walkouts. Let’s build on this global outrage over the U.S. role as the “enabler” of this genocide!

Global support for Palestine

On a world scale, people side with Palestine, whose resistance is our resistance. The liberation of Palestine is an important step in the liberation of humanity.

October 7 opened a new chapter in the worldwide class war. The Israeli regime’s genocidal crimes against the people of Gaza demand our international solidarity.

Faced with an unwinnable quagmire, the U.S. and Israel have expanded this war. Just this week, they bombed Muslims in Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Three days ago, they blew up two main natural gas pipelines in Iran, leaving millions of Iranians without heat and cooking fuel in winter. This is the way the U.S. and Israel fight wars — they target essential civilian infrastructure.

The U.S. and NATO countries cut off all food, medical care and schools to all Palestinians — even in Jordan and Lebanon, and on the West Bank, by cutting off funding to UNRWA [United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East].

I raise all of this, because the U.S. media and politicians claim they want to protect Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. The sheer hypocrisy of this claim is blatant. Yet it is the basis of the sanctions! This false charge is a big weapon in the war on China and in lining up and demanding compliance of all U.S. allies against China.

Thousands of Volkswagen, Audi, and Porsche cars are impounded on ships at U.S. ports, just because they include a small Chinese electronic part. These German auto corporations are told they must pay U.S. fines, remove the offending part and agree to U.S. charges against China regarding Xinjiang.

Bales of clothing made in Vietnam and Malaysia go through isotopic testing at U.S. Customs. If even a thread of cotton comes from Xinjiang, the clothing is destroyed. This is because the U.S. authorities allege there is slave labor in Xinjiang — even though Xinjiang’s cotton industry is fully mechanized.

Anti-war activists need to militantly oppose the wanton use of economic sanctions, which are used against not only China but a total of 40 countries, inhabited by one-third of the world’s population. Applying sanctions is a powerful weapon of economic destabilization.

However, this is a double-edged sword. Enforcement of these sanctions now widens U.S. isolation. They intensify trade wars with Washington’s imperialist “partners” — or are they better called imperialist rivals?

Much to the frustration of U.S. imperialism, sanctioned countries are finding new roads to cooperation and trade.

Continue reading Hands off China! Full solidarity with Palestine!