On Sunday 21 September, Friends of Socialist China (FoSC) and the International Manifesto Group (IMG) jointly organised a webinar on the theme, ‘World War Against Fascism: Remembering China’s Role in Victory 80 Years On’.

Speakers were:

- Ken Hammond (Historian and China scholar)

- Chen Weihua (Former EU bureau chief of China Daily)

- Jodie Evans (Co-founder of Code Pink)

- Jenny Clegg (Author and peace activist)

- Keith Bennett (Co-editor of Friends of Socialist China)

- KJ Noh (Journalist, writer and educator)

- Radhika Desai (International Manifesto Group), Moderator.

Below we carry the full text of Keith’s contribution. (It was shortened somewhat on delivery due to time constraints.)

The livestream of the webinar may be viewed here. And all the individual speeches as delivered may be found on the IMG’s YouTube channel.

On May 8, 1945, people in Britain celebrated VE Day. Six years of all-out war in Europe against Nazi and fascist tyranny had come to a victorious conclusion.

But whilst the nation struggled with a collective hangover the next day, it did so with the knowledge that the war in East and Southeast Asia, and in the Pacific, continued. And, at that point, nobody could be sure for how long.

Given the circumstances of the time, the war in the East may have seemed remote to many. But not to those whose loved ones were fighting in Burma or elsewhere or worse still were enduring the dreadful cruelty that characterised being a Japanese Prisoner of War.

While, as events transpired, the war in Asia-Pacific was to last just a few more months – due not least to the decisive intervention of the Soviet Red Army rather than to the criminal bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – this does serve to underline that the world anti-fascist war began first in the East, specifically in China, and that it lasted the longest.

Conventional British history would have us believe that the war began on September 3, 1939. Although it may not have seemed that way to the peoples of Spain, whose courageous fight against fascism began in 1936. Or to the people of Ethiopia – their country invaded by fascist Italy the previous year.

But the Chinese people’s war of resistance against Japanese aggression began in 1931, after Japan rigged up the puppet state of Manchukuo in northeast China.

This in turn became a nationwide war of resistance in 1937, with the Marco Polo, or Lugou, Bridge Incident heralding Japan’s all out invasion.

At that time, while progressive people around the world rallied to the support of China, the only state to take a clear stand in support of the Chinese people’s resistance was the USSR. And this clearly impacted on the entire geopolitical pattern in the region.

As President Xi Jinping noted in his article for the Russian media, published just prior to his state visit to attend the victory celebrations in Moscow this May: “In the darkest hours of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, the Soviet Volunteer Group, which was part of the Soviet Air Force, came to Nanjing, Wuhan and Chongqing to fight alongside the Chinese people, bravely engaging Japanese invaders in aerial combat—many sacrificing their precious lives.”

And as Hu Jintao said in 2005, marking the 60th anniversary of the Chinese people’s victory: “The victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese aggression was inseparable from the sympathy and support of all the peace- and justice-loving countries and peoples, international organisations and various anti-fascist forces. The Soviet Union was the first to provide invaluable aid to the Chinese people in the war.”

The Soviet contribution to the defeat of Japanese militarism did not begin with the declaration of war on August 8, 1945, the date agreed between the USSR, the United States and Britain at Yalta.

A key front was opened more than ten years previously in the Mongolian People’s Republic, with hundreds of clashes on the border with the so-called Manchukuo starting from January 1935.

As tensions mounted, it clearly became a matter of when not if a major confrontation would take place between Soviet and Japanese forces in or adjacent to Mongolia. The stakes would be high. A decisive Soviet defeat would likely prompt a full-scale Japanese invasion of the Soviet Union, with the equal likelihood that this would prompt a further attack on the Soviet Union from the West, whereas a decisive Soviet victory would contain the Japanese threat for a considerable period and allow the Soviet Union relative freedom to devote its attentions to preparation to meet an attack from the West.

That major confrontation was to take place from May to September 1939. Known as the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, after the river of the same name, this little-known conflict actually deserves to be known as a key battle that shaped the entire subsequent course of the Second World War.

Just one day after the Red Army forces, commanded by Marshal Zhukov, won a decisive victory in Mongolia, Hitler invaded Poland.

One western military historian has described the significance of the Battle of Khalkhin Gol as follows:

“Although this engagement is little-known in the West, it had profound implications on the conduct of World War II. It may be said to be the first decisive battle of World War II, because it determined that the two principal Axis powers, Germany and Japan, would never geographically link up their areas of control through Russia. The defeat convinced the Imperial General Staff in Tokyo that the policy of the North Strike group, favoured by the army, which wanted to seize Siberia as far as Lake Baikal for its resources, was untenable. Instead, the South Strike group, favoured by the navy, which wanted to seize the resources of southeast Asia… gained the ascendancy, leading directly to the attack on Pearl Harbour two and a half years later in December 1941. The Japanese would never make an offensive movement towards Russia again.”

Had the USSR been forced to fight on two fronts simultaneously, the outcome of the war may have been very different, both in Asia and Europe, with cataclysmic consequences for humanity.

Two factors were crucial in this. Besides the clear-cut Soviet victory at Khalkin Gol, what must be acknowledged above all is the Chinese people’s heroic resistance. Alongside the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet peoples, it was the Chinese people who shouldered the greatest burden and made the greatest national sacrifice in the world people’s struggle against fascism.

It was with the strong leadership of the Communist Party of China, which called for nationwide resistance by the whole Chinese nation and people first and most consistently, and with a national united front that would not have been created or sustained without the party’s consistent, persevering, skillful, tenacious and self-sacrificing efforts, that, in the words of Hu Jintao, “For a long time, we Chinese contained and pinned down the main forces of Japanese militarism in the China theatre and annihilated more than 1.5 million Japanese troops. This played a decisive role in the total defeat of the Japanese aggressors. The war of resistance lent a strategic support to battles of China’s allies, assisted the strategic operations in the Europe and Pacific theatres, and restrained and disrupted the attempt of Japanese, German and Italian fascists to coordinate their strategic operations.”

The struggles of the Chinese, Soviet and Mongolian peoples were also closely coordinated with that of the Korean people, who, their country having been colonised in 1910, had suffered under the iron heel of Japanese imperialism for longest. Although the Korean people had never ceased their fight for independence, for example with their Declaration of Independence in the March 1st, 1919, movement, as in China, the bourgeois nationalists proved themselves incapable of effectively leading the anti-fascist, anti-imperialist struggle.

That task fell to the Korean communists led by Kim Il Sung, a brilliant guerrilla commander, who for much of this time was based in northeast China.

In the summer of 1942, the Soviet Union took the initiative to form the International Allied Forces together with Chinese and Korean communists and other patriots. Kim Il Sung wrote in his Memoirs, ‘With the Century’:

“With the organisation of the IAF, a great change took place in our armed struggle. It can be said that, with the formation of the allied forces as a turning point, we switched from the stage of our joint struggle with the Chinese people to the stage of extensive joint struggle, which meant an alliance of the armed forces of Korea, China and the Soviet Union, the stage of a new common front joining the mainstream of the worldwide anti-imperialist, anti-fascist struggle.

“Even when the Soviet Union badly needed the strength of another single regiment or a single battalion because of the extremely difficult situation at the front, it never touched the allied forces but helped them so that they could make full preparations for the showdown against the Japanese imperialists.”

Of course, within the overall context of the anti-fascist war, different forces had different class natures and hence different war aims and strategies.

Hence, just as bourgeois governments in Europe, from France to Norway to Greece, folded in the face of Nazi aggression, so supposed British colonial strongholds and fortresses, like Hong Kong and Singapore, fell to the advancing Japanese forces like skittles in a bowling alley.

Throughout the region, it was the communists and the communist-led forces who led the resistance, fighting a protracted people’s war, tying down the Japanese Imperial Army, surrounding them and ultimately defeating them. In China, Korea, Vietnam, Burma, Malaya, Indonesia, the Philippines and elsewhere.

These different class interests – essentially fighting for liberation or fighting for empire – clearly manifested themselves on the conclusion of the war.

Hence, Ho Chi Minh’s declaration of Vietnam’s independence on September 2, 1945, was met with British forces attempting to control the country until the French colonialists could return, this in turn leading to three further decades of war that would sweep across and devastate Laos and Cambodia, too.

US forces landed in Korea, occupied the southern part of the peninsula, suppressing the people’s committees and imposing a white terror, leading directly to a genocidal war five years later.

The Philippines communists returned to armed struggle, this time against US neo-colonial domination, in 1946.

The leader of the Communist Party of Malaya, Chin Peng, was awarded the OBE (Order of the British Empire) for his wartime role fighting the Japanese, but by 1948 was leading a renewed armed struggle against British imperialism and subsequently against neo-colonialism – one that was only finally comcluded with a peace agreement signed between the Communist Party of Malaya and the Malaysian government in southern Thailand in December 1989.

In China, with Chiang Kai Shek, refusing to abide by the outcome of the Chongqing negotiations and reverting to visceral anti-communist form, the revolutionary civil war, or war of liberation, broke out in 1946, leading three years later to the founding of the People’s Republic of China, which stands today as the single greatest event in history’s long march towards human liberation.

To a great extent, all this could be and indeed was foreseen. Displaying the strategic and tactical brilliance that consistently characterised his approach to international affairs, in his 1940 article, On Policy, Mao Zedong wrote:

“The Communist Party opposes all imperialism, but we make a distinction between Japanese imperialism which is now committing aggression against China and the imperialist powers which are not doing so now, between German and Italian imperialism which are allies of Japan and have recognized ‘Manchukuo’ and British and US imperialism which are opposed to Japan, and between the Britain and the United States of yesterday which followed a Munich policy in the Far East and undermined China’s resistance to Japan, and the Britain and the United States of today which have abandoned this policy and are now in favour of China’s resistance. Our tactics are guided by one and the same principle: to make use of contradictions, win over the many oppose the few and crush our enemies one by one.”

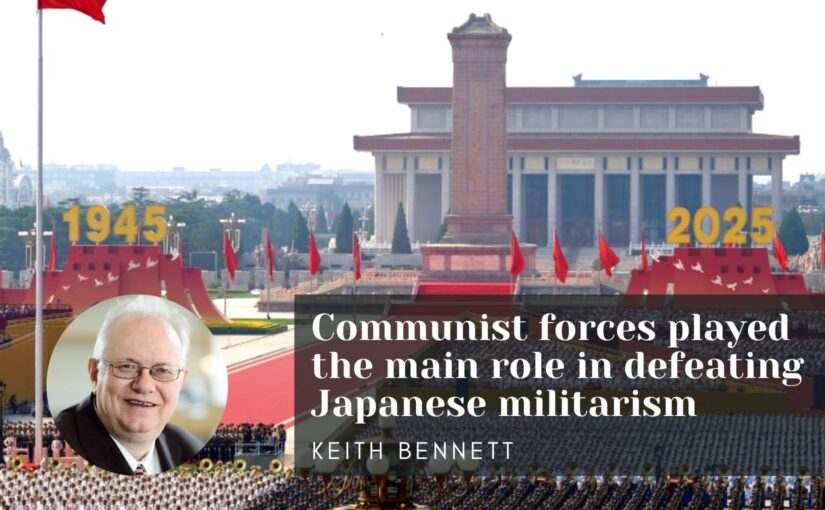

Viewed in this light we can understand – although the western powers and western media either could not or would not – why, on the rostrum of Beijing’s Tienanmen Square, on the 80th anniversary of the September 3rd victory, President Xi Jinping was flanked by Russia’s Vladimir Putin and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s Kim Jong Un. And why they were joined by the Presidents of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan Belarus, and Azerbaijan, and the Prime Minister of Armenia, from the former USSR; by the King of Cambodia, the Presidents of Mongolia, Vietnam, Laos and Indonesia, the Acting President of Myanmar, the Prime Minister of Malaysia, the Deputy Prime Minister of Singapore, the President of the National Parliament of Timor-Leste, and the Speaker of the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea, from among China’s neighbours who together faced Japanese aggression; and by other leaders, such as the President of Serbia, whose people waged the most tenacious anti-fascist guerrilla struggle in Europe, along with those who today who stand on the frontlines of the anti-imperialist struggle, including the Presidents of Cuba, Iran and Zimbabwe, and Nicaragua’s Presidential Adviser.

That the leaders of the United States, Britain and the other imperialist powers chose to absent themselves not only shows who truly carried the main burden of the anti-fascist struggle but also who remains committed to upholding the truth and a correct understanding of World War II and its outcome and hence to standing against fascism and war today.