This article by Casey Ho-yuk Wan, an attorney and independent researcher, provides a rigorous critique of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ recently-released Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the People’s Republic of China.

Casey gives an overview of the contents of the Assessment, noting that it makes no reference to the most serious charge against China – ie that it engaged in a genocide against Uygur people in Xinjiang – and furthermore that its accusations are couched in deliberately ambiguous language, for example “[China’s actions] may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity”.

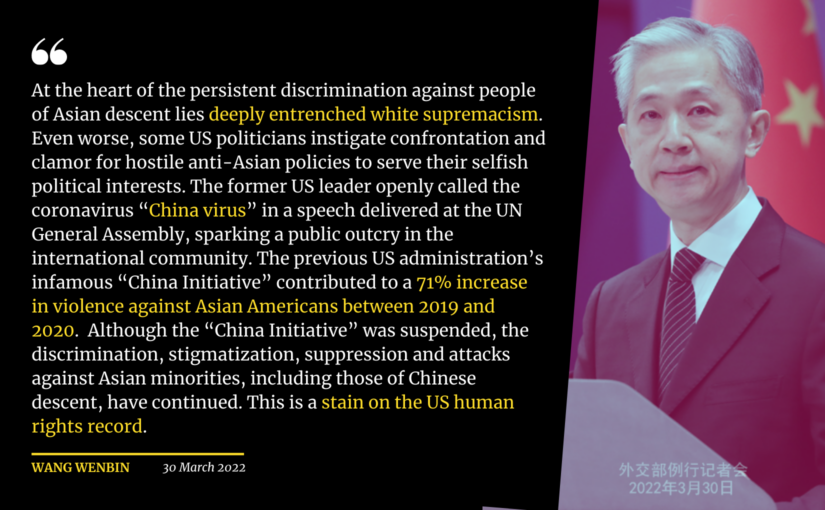

The author observes that Chinese voices are near-absent from the source interviews, in particular Chinese NGOs, academics and individuals. The Assessment does however extensively cite US-funded NGOs such as the Australian Strategic Policy Institute and ideologically-driven anti-communist researchers such as Adrian Zenz. As such, the Assessment suffers from a profound bias. Meanwhile it makes no mention of human rights that the Chinese government has been very actively promoting in Xinjiang: poverty alleviation, development, and safety from terrorist attacks.

Casey makes the crucially important point that the Assessment does not enjoy a mandate from the General Assembly or the Human Rights Council. Through a detailed analysis of voting and statements at the United Nations, he makes it clear that the majority of the world’s countries – and the vast majority of Muslim-majority countries – support China’s position and reject the accusations that have been thrown around by the US and its allies regarding Xinjiang. As such, and given the OHCHR’s relative silence in relation to persistent human rights abuses by the imperialist powers, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the Assessment is politically-motived, produced under pressure from the US, and designed to contribute to the escalating New Cold War. One by-product is that the Assessment “will likely weaken the credibility of the OHCHR in the eyes of the Global South”, thereby causing lasting damage to the entire UN-based human rights framework.

The article is fairly long and detailed, but deserves to be thoroughly read.

Introduction

On 31 August 2022, shortly before the tenure of Michelle Bachelet as UN High Commissioner for Human Rights ended, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released its “Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the People’s Republic of China.”[1]

This write-up is a response to the “Assessment”, which raises serious doubts as to the impartiality, objectivity, and non-selectivity of the OHCHR’s work with implications for the credibility not merely of the Assessment, but of the OHCHR as a responsible international organ capable of conducting human rights work in a constructive manner while avoiding double standards and politicization. This write-up will also speculate on potential political consequences of the Assessment. In summary, the Assessment risks the discrediting of the OHCHR and the politicization of the global human rights regime the OHCHR is mandated to promote, while likely serving to widen the chasm between the OHCHR and the Global South and to aggravate ongoing and potential international conflicts.

The Contents of the Assessment

It is important to identify what the Assessment has stated. While much has been made by mainstream media of the Assessment’s seeming indictment of China’s crimes against humanity[2], the Assessment cannot be definitely said to be a sort of indictment or supposition of fact. Paragraph 148 of the Assessment provides:

The extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups, pursuant to law and policy, in context of restrictions and deprivation more generally of fundamental rights enjoyed individually and collectively, may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.

This sentence is deliberately ambiguous. In particular, the use of the word “may” can take on two different meanings. The sentence could be stating that, given what the OHCHR currently knows, the extent of arbitrary detention likely constitutes crimes against humanity. This interpretation would be strengthened had the sentence been placed in present perfect tense – that the extent of arbitrary detention may have constituted crimes against humanity. Instead, the sentence placed in the present tense gives rise to a second interpretation: that, given the right circumstances, the extent of arbitrary detention could give rise to the level of crimes against humanity. In other words, “may” could imply either a preliminary finding or supposition of fact, or the mere possibility of a fact.

Leaving the sentence ambiguous in this manner seems to serve the purpose of staking out a position but without committing the OHCHR to find one way or the other in regards to China. At any rate, the sentence is by no means a definitive statement of fact that China committed crimes against humanity. The Assessment is also notable for making no mention of genocide, making only a passing reference to slavery, and presenting no definitive finding on forced labor in Xinjiang.

The Assessment limits itself to the evaluation of certain human rights concerns: China’s laws and policies regarding counter-terrorism and extremism; imprisonment and deprivation of liberty (particularly in regards to the vocational education and training centers (VETCs)); conditions and treatment in the VETCs; religious, cultural, and linguistic identity and expression; privacy and freedom of movement; reproductive rights; employment and labor; family separations and enforced disappearances; and intimidations, threats, and reprisals.

A full review of the Assessment is beyond the scope of this write-up. Suffice to say that in each of the areas listed above, the OHCHR found great cause to be concerned, and have definitively concluded that “serious human rights violations have been committed” in Xinjiang that are “characterized by a discriminatory component.”

Concerns Regarding the Assessment

UN General Assembly Resolution 48/141 of 1994 established the post of High Commissioner of Human Rights, who would be “the United Nations official with principal responsibility for United Nations human rights activities under the direction and authority of the Secretary-General; within the framework of the overall competence, authority and decisions of the General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council and the Commission on Human Rights.” Among other responsibilities, the High Commissioner of Human Rights would “promote and protect the effective enjoyment by all of all civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights.”

Resolution 48/141 further emphasized the “need for the promotion and protection of all human rights to be guided by the principles of impartiality, objectivity and non-selectivity, in the spirit of constructive international dialogue and cooperation…” These principles were reaffirmed by UN General Assembly Resolution 60/251 of 2006, which established the Human Rights Council (HRC) to replace the Commission on Human Rights. Resolution 60/251 further aspired to eliminate “double standards and politicization” of human rights issues. Resolution 48/141 also requires the High Commissioner to “respect the sovereignty, territorial integrity and domestic jurisdiction of States”, as well as to recognize that “all human rights – civil, cultural, economic, political and social – are universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated” and to “promote and protect the realization of the right to development”.

The Assessment raises serious concerns about the work of the OHCHR, as the Assessment fails to live up to the principles of impartiality, objectivity, and non-selectivity, risking the proliferation of double standards and politicization in contemporary human rights work.

The Assessment is one-sided, and sets a worrying precedent

The Assessment claims a “rigorous review of documentary material currently available to the Office, with its credibility assessed in accordance with standard human rights methodology.” It pays special attention to the laws, policies, data, and statements of the Government of China, including document leaks by journalists alleged (and accepted by the OHCHR) to be of an official nature. Supplementing the review of documentary material, the OHCHR interviewed 40 individuals with claimed direct and first-hand knowledge of the matter at hand.

However, a review of the 306 footnotes of the Assessment reveals a concerning omission. Citations in the Assessment overwhelmingly consist of Chinese governmental material, “the vast amount of research that has been completed by non-governmental organizations, researchers, journalists and academics over the last years”, and the interviewed individuals. Missing from citations entirely are non-government Chinese material, including material from Chinese non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academics, and individuals. Also missing are Chinese-language sources apart from Chinese governmental materials such as laws and regulations, and mass media reporting.

Continue reading Bachelet’s “Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in Xinjiang” Risks Discrediting the OHCHR and Politicizing the Human Rights Regime