We are pleased to republish the following article on the revolutionary life of Liu Liangmo (1909-1988), a Chinese anti-imperialist, progressive Christian, and pioneer of solidarity between the African-American people and the Chinese revolution. Written by Eugene Puryear, it was originally published by Liberation School, an initiative of the US Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL). As Comrade Puryear explains:

“While excavating this history is important in its own right, it is even more so because the promise and the contradictions of these wartime attempts to build unity among the exploited and oppressed hold important lessons for our own time.”

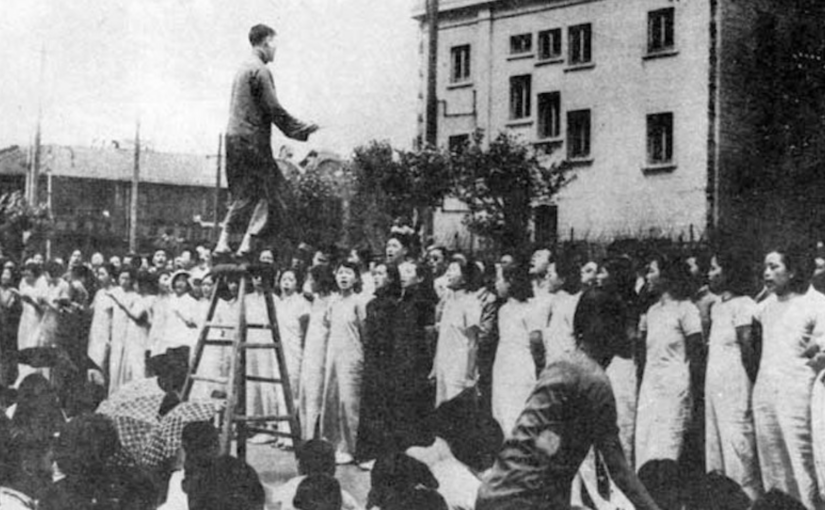

Liu’s political activity began with the progressive cultural circles in Shanghai linked to the underground Chinese Communist Party, where he pioneered the use of mass singing of patriotic and anti-imperialist songs as a means of popular mobilization.

In 1940, he left China for the United States to work with United China Relief, which worked to build support for the Chinese people’s resistance to Japanese aggression, as an arm of the united front that had been re-established between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang. Once in the United States, his interest in cultural work inevitably and rapidly drew him into a close association and friendship with Paul Robeson, with whose work he had already become familiar before leaving China.

Liu began writing regularly for the progressive black press in the United States. In 1942, he reported on a New York rally, also attended by Claudia Jones, demanding the opening of a Second Front in western Europe, at a time when the Soviet people were heroically resisting the Nazis at Stalingrad. Clearly linking this demand to the struggle for the liberation of oppressed people everywhere, he wrote:

“Forty thousand New Yorkers … attended the Second Front rally at Union Square… I was very much interested in the placards which people carried … the most outstanding ones are: ‘Smash Race Discrimination,’ ‘Equal Rights to Negroes NOW!’ and ‘Free India NOW!… It is interesting to me because it clearly demonstrated the inter-relationship of these problems … the reactionaries and Tories don’t want to see Soviet Russia win; neither do they want India to be free, nor Negro people to have equal rights so they delay the opening of a Second Front, they delay in giving freedom to India, and they keep on Jim-Crowing the Negro people in this country. But the people of the world black and white and brown together demand that: a Second Front be opened in Europe NOW; Free India NOW; Equal rights to Negroes NOW.”

Liu returned to China after liberation and the founding of the People’s Republic, but his work and example undoubtedly helped to lay important foundations for ensuing decades of collaboration and solidarity between the black liberation movement and socialist China. Mentioning a number of key people who contributed to this, Puryear writes:

“Harry Belafonte would tell Paul Robeson’s confidante Helen Rosen of his fascination with New China: ‘When Alassane Diop, Guinea’s former Minister of Communications, came back from a visit to the new China in the early 50s, he told me that the city of Shanghai was clean and beautiful, that its citizens had a decency and spirit unequaled anywhere else in the world. I asked myself how a nation devastated by war and riddled with hunger, disease, and illiteracy was able to order the lives of 800 million citizens. I erupted into an insatiable curiosity about China.'”

The great singer, actor and lifelong progressive activist and freedom fighter, Harry Belafonte, passed away this April 25th at the age of 96.

A second article by Puryear sets out the author’s view of the communist movement’s popular front policy, with particular reference to Liu’s work in the United States.

Introduction

Liu Liangmo (1909-1988) was a prominent Chinese anti-imperialist, religious leader and, from 1942-1945, columnist for the Pittsburgh Courier—at that time the nation’s widest circulating Black newspaper. Liu’s columns (and actions as an organizer) were a significant part of efforts by progressive Chinese people, on the mainland and in the diaspora, to build alliances with the Black Liberation movement as part of a broader effort to shape the post-war world.

His words linked the causes of ending colonialism, imperialism, and race discrimination—from the Yangtze to the Ganges to the Mississippi—mirroring the words and actions of millions of others involved in similarly-minded struggles around the world, including Liu’s favorite U.S. singer: Paul Robeson.

Liu’s columns represent the efforts of Communist and aligned currents to turn the allied effort in the favor of the exploited and the oppressed. This was counteracted in the so-called “Cold War,” as imperialist forces worked to make the world “safe for capitalism” in the wake of the World War II.

His columns and activities offer interesting insight into the struggle within the “Second United Front” in China between the Nationalist Kuomintang and the Communists during the Second World War and their differing approaches to the post-war world: whether China should be an anti-colonial vanguard or seek inclusion in the imperialist “great power” club. The “Nationalist” Chinese government’s chose the latter, heavily impacting their approach to racism in the US.

On the other side, the nascent global left-wing coalition hoped to use the new leverage the war created: notably the curtailing of the anti-Bolshevik crusade and the embrace of the USSR as an ally, the attendant rise in the prestige of communism, and the need to mobilize colonial and all resources on the U.S. home-front. This leverage opened some space for the first legal labor and political organizations in colonial Africa and the Black Liberation movement in the U.S. Also critical was the importance of India and China to the overall allied effort against Germany, Italy, and Japan; to end colonialism, Jim Crow, and the old imperialism.

These were dangerous dreams, which is exactly why they were, on the whole, dashed and distorted by the Cold War crusade to prevent the consolidation of socialist and progressive movements, particularly in the colonial and de-colonizing world, where the imperial powers knew no bounds of brutality or depravity.

While excavating this history is important in its own right, it is even more so because the promise and the contradictions of these wartime attempts to build unity among the exploited and oppressed hold important lessons for our own time.

The song leader

Born in 1909 in Ningbo, China, Liu, like many Chinese people at that time, came into contact with the missionary movement early in life. In middle school, Liu converted to Christianity, quickly becoming involved in the YMCA. His involvement in the Christian church led him to attend the Baptist-established University of Shanghai. He took an interest in singing and joined the university choir. Around the same time, Liu became a part of an anti-imperialist fervor that swept the nation after Japan seized Manchuria in northeastern China in 1931-1932.

Within a broad-based movement in Shanghai, a left-wing cultural circle emerged with links to the underground Chinese Communist Party, which encouraged the use of cultural forms as political weapons. Mass singing had already gained popularity due to religious movements and army songs taken up by varying warlords and communist guerrilla armies to raise morale and build unity while on the march.

Liu recognized mass singing could be used as a protest instrument, that mass singing of patriotic and anti-imperialist songs through both the numbers involved and the power of the songs themselves would show how people were resisting Japanese encroachments. He explained:

“If we Chinese want to break free of imperialism’s iron shackles…if we want China to exert itself, our people must be able to loudly and vigorously sing powerful songs full of spirit and vitality. If the people of China can sing these songs, no doubt the sound will shake the earth. Any youth who can sing should spread the “people’s song” movement to each province, city, county, and countryside. The dawning of a new China will arrive when all the people of China can sing these majestic and powerful songs” [1].

Liu decided to move his singing project out of the church and into student groups, where it predominated and organized a “mass singing club for some sixty underprivileged youth—clerks, doorkeepers, office boys, elevator operators, and apprentices” [2]. This group would come to be known as the People’s Song Association and, by 1936, would grow to over 1,000 members.

One of the principal songs in their arsenal was “March of the Volunteers,” written by a fellow leftist cultural worker in Shanghai: Nie Er. The song became famous and, since 1978, has been the official National Anthem of the People’s Republic of China.

The mass song movement in Shanghai was caught in the crosswinds of Chinese politics as it was not simply anti-Japanese but was also critical of the “Nationalist” Koumintang government headed by Chiang Kai-Shek, whose forces at first sought to suppress the song movement as “subversive.” However, the opening of the “Second United Front” between the Communists and Nationalists, who joined together to oppose Japan—which was on the verge of invading all of China—opened up new space for the movement. On the orders of Chiang himself, Liu was sent to the front to teach mass singing to the troops.

Under the auspices of the YMCA, between 1937-1939 Liu and others taught songs to thousands of soldiers and their officers. They trained students to be mass song leaders and organized both to bridge the gap between soldiers and civilians through shared songs and collective singing. His work was greatly facilitated by working under command of the Nationalist General Fu Zuoyi, who later achieved great renown in the country for embracing the Communists and the Chinese revolution in 1949, going on to hold high office in the People’s Republic.

The success of Liu and his compatriots aroused suspicion among the conservative sectors of Chiang’s government who felt—not entirely incorrectly—that the mass singing movement facilitated Communist organizing. They ultimately shut down the project. Liu was further harried and harassed while attempting to regroup in various parts of the country due to his work with the Communist New Fourth Army and for meeting with Communist leader Zhou Enlai.

In a precarious situation in China, Liu left for the United States in 1940 to work with the United China Relief, the U.S. fundraising arm for the United Front forces in China that worked to build support for the battle against the Japanese war machine.

“China Speaks”

Liu quickly jumped into both cultural and political efforts. Notably, through the broader left-wing cultural milieu in the Chinese-American community, in 1940 Liu reached out to Paul Robeson, whose songs he knew from back in China. Just 30 minutes after the phone call, Robeson went to meet Liu. Working with others, Liu translated Chinese patriotic songs into English. Robeson sang these songs in both Mandarin and English at rallies to raise funds for China on the basis of these compositions. In 1941, they released an album together named after “Chee Lai”—or “March of the Volunteers”—a song emphasizing the resistance of “bond slaves,” which Robeson felt best articulated the aspirations of the world’s oppressed and exploited in their liberation struggle [3].

Traveling the country for United China Relief, Liu sometimes appeared with Americans of considerable power, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1942, he spoke at Lincoln University, one of the most prominent Historically Black Colleges and Universities. There he linked the fight against fascism in Europe and Asia with the fight against Jim Crow racism in the U.S. In the audience was P.L. Pratis, editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, the largest Black newspaper in the country. Pratis offered Liu a column to expound upon his views on a weekly basis.

Titled “China Speaks,” Liu’s column carried his observations on a range of issues about China and the broader struggle against fascism and white supremacy. Liu’s general political perspective could be encapsulated in an article from 1943, titiled “Must Fight Fascism at Home and Abroad to Keep This a People’s War.”

In a community meeting in Cincinnati, someone asked if there might be “another war” if the war against the Axis ended without “liberation…for oppressed peoples.” Liu responded, “There can be no peace in the world until all the people are free, and all forces of fascism and oppression are defeated.” In his view, “this war could not be won if Negro, Chinese, Indian, and other oppressed people were not liberated.” Liu’s columns consistently linked the efficacy of the war against fascism to the extent to which the Allies embraced anti-colonial and anti-imperialist aims.

He animated this vision through frequent reporting on political mobilizations. In one 1942 column, Liu reported on a left-wing rally demanding the Allies open a second western front against Nazis, as the Soviets were holding them off heroically at Stalingrad in the east. “Forty thousand New Yorkers…attended the Second Front rally at Union Square…I was very much interested in the placards which people carried…the most outstanding one’s are: ‘Smash Race Discrimination,’ ‘Equal Rights to Negroes NOW!’ and ‘Free India NOW!” Liu continued:

“it is interesting to me because it clearly demonstrated the inter-relationship of these problems…the reactionaries and Tories don’t want to see Soviet Russia win; neither do they want India to be free, nor Negro people to have equal rights so they delay the opening of a Second Front, they delay in giving freedom to India, and they keep on jim-crowing the Negro people in this country. But the people of the world black and white and brown together demand that: a Second Front be opened in Europe NOW; Free India NOW; Equal rights to Negroes NOW” [5].

Comrades-in-arms

Liu clearly took great care to uplift the most uncompromising voices for Black freedom in his columns. In the above article on the second front, for instance, he quoted the Black newspaper the California Eagle, whose editorial line was informed by the radical political stances of its publisher, Charlotta Bass [6].

Paul Robeson’s words appear throughout Liu’s articles in the Courier. In one, he reported on a series of letters with Indian freedom fighter Rajni Patel, Robeson’s “good friend:”

“The fact that because the Negro people are jim-crowed, persecuted, denied their full rights, they have an even greater stake in this war than the white people…in the sense that [the] war has as its aim the destruction of the most reactionary forces in the world…[creating] unparalleled opportunities for the Negro people together with the oppressed millions of Asia, Africa and Latin America, to move forward freedom and equality” [7].

In a similar vein, Liu spoke alongside Robeson at a “Free India” rally sponsored by the Council on African Affairs in the fall of 1942 [8]. Around 4,000 people attended and also heard from Harlem City Councilmember Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Dr. Channing Tobias of the YMCA, and Mike Quill, president of the Transport Workers Union [9]. Robeson was also the honorary Chairman of the China Defense League, the leading relief organization in wartime China, led by Soong Ching-Ling, a staunch anti-imperialist and one of China’s most influential leaders.

Thus, Liu’s interventions in the Courier—and political interventions more broadly—discussed China‘s struggles within a global worldview aimed at building a particular coalition rooted in the alliance between the Soviet Union and the Communist-led and associated elements of the anti-colonial and labor movements. In addition to Robeson and Bass, this milleu included people like Claudia Jones, whose FBI tail spotted her on the speakers platform of the same 1942 Second Front rally [10]. Langston Hughes was also a part of this grouping [11].

Liu sought to create a strategic connection between these progressive Black and labor forces, the left in China, and the progressive Chinese-American community, appealing directly to the grassroots of the Black masses through the mass circulation of the Courier.

The Pacific color line

Liu’s column addressed the issue of discrimination against Black Americans by Chinese people. In one, he reported on a letter from a Black reader who, along with a friend, was subjected to racism at a Chinese restaurant in New York City. Liu agreed that some Chinese people were “Jim-Crowistic” and sought to “raise their station” by enforcing prevailing Jim Crow attitudes. He promised prompt, personal action, telling his readers to “let me know as specific as possible, the Jim Crow Chinese individuals and shops that you know and I will publish them in the Chinese newspapers” to rally anti-racist Chinese forces against them.

A few months earlier, Liu highlighted that the Editor of the China Daily News, the largest circulating Chinese paper on the East Coast, spoke out against anti-Black racism and preached unity in the fight against national oppression. After the Courier detailed discrimination against Black customers at Chinese owned establishments on the West Coast, the Chinese Consul promised that “every effort” would be made to eliminate said discrimination, and asked for specific complaints as well so they could confront the issue. The Courier editors made sure to include a special note for readers to see Liu’s article in the same issue—the Christmas edition—which included a Christian plea for unity between the Black and Chinese community.

The same issue of the Courier also noted that Liu had translated the Courier article about discrimination against Black patrons in Chinese-owned establishments into Mandarin, and produced a facsimile of the translated article for the China Daily News and the Chinese Journal, two of the largest Chinese newspapers in the U.S. Liu thus pushed Chinese-American papers to cover issues related to racism, noting in one column that Chinese newspapers (presumably at his instigation) started carrying news of all the lynchings in 1942, as well as anti-Poll Tax agitation [12].

The impact of Liu’s efforts is hard to say, but for the Courier’s editorial leadership, it was clearly important to highlight that whatever other contradictions there were, there was a growing cohort of Chinese people willing to stand up to Jim Crow [13].

The overall political struggle among Chinese Americans related to the critical struggle taking place back in China in the United Front against Japan. As Liu himself alluded to, some Chinese thought by discriminating against Blacks, they could mitigate the effects of white supremacy against themselves. Indeed, the United States has made something of an art out of holding out the possibility of limited group uplift to anyone willing to embrace a racial hierarchy where Blacks remained on the bottom. This manifested itself not simply in restaurants in Brooklyn and Santa Monica, but on the international level as well.

The “Two-Line” struggle

Liu was in an interesting position in the U.S. On one hand, he represented United China Relief, an instrument of the United Front in China. However, the United Front was relatively tenuous, and Chiang Kai-Shek was often more interested in weakening the Communists than in fighting Japan and willing to sacrifice the latter goal entirely for the former. So on the one hand, Liu spoke in the United States “for China” as a whole in his Courier column, but his views were not always consistent with Chiang’s government. This was especially clear on issues of national oppression.

Chiang and his co-thinkers were well aware of the political dynamics in the U.S., most notably the stranglehold Jim Crow politics had over everything that happened in Washington, D.C. Anti-racist politics were at best tolerated in official circles, but generally put one on a kind of progressive fringe. It was also critically important from their standpoint to curry as much favor as possible in D.C., because Chiang wanted to leverage support from the Allied forces to marginalize the Communists. This posed a particular problem because a good many Americans were knowledgeable about China and not favorable to Chiang and his “Nationalists.” Their policies reinforcing mass poverty and frequent famines in China, on top of their deeply sectarian fears of losing power to the Communists, contributed significantly to weakening the resistance to the Japanese onslaught since 1936.

To build new friends in Washington, Chiang and his emissaries mainly soft-pedaled racial issues. For instance, on Madame Chiang’s high-profile 1943 tour of the U.S, she declined to mention the issue of Jim Crow and ignored invitations from Black organizations to speak. On the other hand, China won accolades in Black America when the China Blood Bank announced blood donations to China would not be racially segregated [14]. This was especially important for the Black community because the American Red Cross absurdly refused to “mingle” donated blood from Black people with that donated by whites. While the official war propaganda spoke of national unity, donated “Black blood” was given to Black troops and “white blood” to white troops, both of which remained in segregated units. This had an extra sting as it was Dr. Charles Drew, a Black surgeon, who developed the key scientific knowledge for large-scale blood banks being used in the war.

While on its face representing the overall “united front” of anti-Japanese forces in China, Liu clearly represented a very particular line of the Communist-aligned forces. As the war progressed, Liu’s columns reflected the growing divergence between the earnestly anti-imperialist forces—in most cases communist—and those looking to be a new type of exploiter.

Early in the conflict, Liu quoted a statement from Madame Chiang that the war could only be won if “exploitation and Imperialism” were “swept out of existence” [15]. He further reported on Chiang Kai-Shek’s statement to the New York Herald Tribune Forum that “China is not only fighting for her own independence, but also for the liberation of every oppressed nation and people in the world.” In Liu’s words at the time, Chiang was speaking “for all us Chinese people” [16].

However as the war ground on, hints of disagreements and then open polemics started appearing. In May 1943, Liu wrote that the Allies were working to strengthen unnamed “reactionary” and “defeatist” elements among the Chinese United front. He attacked the policies causing hunger and inflation and that any criticism back home was being snuffed out by police forces under the guise of combating “communism” [17].

By 1944, Liu was speaking more openly about the role played by the Communists in the revolution. In the summer that year, he observed how the war effort was harmed by a the Chiang government’s blockade of the Communist-held areas that had “immobilized” over 1 million soldiers. This was all the more galling to Liu because of the social progress taking place in the liberated areas. He wrote for his Courier readers about a recent report from several U.S. journalists who had finally made it to Yenan, the seat of the Communists where, in the words of The New York Times, “Hospitals are built in the caves…They manufacture their own medicines…they manufacture their daily commodities through the development of industrial co-operatives. Considering the fact that this area has been blockaded by the Kuomintang troops…their development is really amazing” [18].

This wasn’t a fluke, but a result of the fact that “democracy is being practiced there,” with a government composed of both United Front parties and locally elected officials. He quoted The New York Times that embracing the Communist forces would “speed victory” over the Japanese [19].

In the last year of WWII, the conflict between the two forces in the United Front was acute. It was clear to just about everyone that any real democracy in China was going to result in a government where Communists had significant influence. Their land reform and governance policies as well as their staunch anti-imperialism in particular brought them great fame. Chiang and the “Nationalists” heightened blunting the Communists, resulting in closing down whatever democratic space they could. They were loath to be wedded to policies that would curb the influence of the landlords and industrialists who backed them.

Liu’s columns in 1945 detailed the state of negotiations between the parties in China on the post-war future. He was keen to reflect the truth that was much less reported in the Western press: the Communists and their allies were the truly democratic ones. He looked to rally support from Black America to use its political influence to support the Chinese negotiating position. He made an implicit link between the broad left-leaning coalition he had sought to rally in the U.S. and Chinese communists. In particular, he declared anti-communism to be the “last trump card” of the fascist forces, which was rearing its head at the war’s end to prevent real “victory” in the sense that Liu always presented it: victory over facism, colonialism, “jim-crow-ism,” and the “old imperialisms.” Asking his readers:

“Haven’t you heard alot lately about the attacks against the ‘Commies,’ the ‘Stallinists,’ and their ‘fellow-travelers?’ haven’t you heard such double talk as ‘the ally of today (meaning Soviet Russia) may be the enemy of tomorrow?’… Let us expose all these enemy agents, be they in China, in Europe, or in this country before they can wreck our country, the United Nations and the peace of the world” [20].

The issue quickly came to a head with respect to the post-war settlement because of the Chiang’s government position on addressing racism and colonialism. A deeply offensive incident arose when Chiang sought to block Black U.S. troops, the same ones who built and conveyed the majority of allied supplies to China along the Ledo Road from the country. The Chicago Defender broke the controversy, causing significant anger across Black America. Notably, the Defender did include the testimony of one those Black soldiers that, “We have worked with the Chinese and they are fine fellows to work with. For some 15 months they have treated us like brothers” [21].

At the UN conference, Chiang’s government backed off previous intimations they would support an explicit plank on racial discrimination in the new UN’s human rights document, which was a major campaigning point around the UN for Black organizations in the United States. The Chinese Communist delegate, Dong Biwu, was totally different [22]. He was, in the words of Alphaeus Hunton, the principal Pan-African organizer in the U.S., “ostracized” by China’s nationalist-led delegation for outspokenly attacking racism in the U.S., including in the pages of the Chicago Defender [23]. Hunton especially noted Biwu’s statement about why the Chinese Communists extended their solidarity to the exploited and oppressed: “The only help we have had has come from the common peoples of the world, from Indians, Canadians, Negroes, Russians and even some Englishmen…is it any wonder we prefer to discriminate against fascist governments–and not against the common people of any race [24]?

Courier publisher P.L. Pratis, however, did not take those distinctions into account when he decided to end Liu’s column in 1945 in order to send a message to China about neglecting Black-Asian solidarity. This was unfortunate because Liu’s voice was exactly the type Chiang sought to silence, one calling for solidarity with the oppressed and exploited, not the capitalist-imperialists.

Liu would continue to write for China Daily News for a few years, which included a 1950 paean to Paul Robeson. However, the pro-Communist Chinese community was persecuted along with the rest of the left in the rising Cold War, and Liu returned to now Communist-led China in 1949, or what was becoming known as “New China.” A prominent voice in favor of the new Chinese government, Liu rapidly ascended to the upper echelons of the “New Democracy” as a prominent representative of the Christian community. He became instrumental in the “Three-Self Patriotic Movement,” which became the dominant current of Protestantism in China.

The Three-Self Movement was rooted in an affinity with the basic anti-imperialist, anti-colonial principles of the Chinese revolution and the “New China.” It sought to establish a Christian denomination that explicitly countered the cultural imperialism of Western Christian missionaries and embraced the ideas of socialist construction. Liu wrote a book, How America Uses Religion to Invade China, in support of the broader movement and also led campaigns to combat “imperialism, bandits, and wicked tyrants” and to “arouse the righteous indignation and accusations of Christians towards imperialism and bad elements in the churches” [25].

From the 1950s into the 1970s, the People’s Republic of China was consistent with the policy espoused in the 1940s for an alliance with the Black Liberation Movement. Friends of China included W.E.B. and Shirley Graham Du Bois, Vicki Garvin, Robert F. Williams, and the Black Panthers. A number of John O. Killens’ novels that skewered racism were translated and taught in Chinese colleges. Imari Obadele, central leader of the Republic of New Africa, described Lin Biao, the head of the People’s Liberation Army, as one of their “leading supporters” [26]. Harry Belafonte would tell Paul Robeson’s confidante Helen Rosen of his fascination with New China:

“When Alassane Diop, Guinea’s former Minister of Communications, came back from a visit to the new China in the early 50s, he told me that the city of Shanghai was clean and beautiful, that its citizens had a decency and spirit unequaled anywhere else in the world. I asked myself how a nation devastated by war and riddled with hunger,disease, and illiteracy was able to order the lives of 8oo million citizens. I erupted into an insatiable curiosity about China” [27].

In 1978, as China started making numerous changes that would lay the groundwork for the China of today, Liu became part of the government of Shanghai, the same city where, five decades earlier, he led the masses in protest songs. He eventually rose to become vice-chairman of the Shanghai Political Consultative Conference in 1982. Liu passed away in 1988, having lived a full life in service to the New China, from its earliest embryos to its full development, embodying its best principles of internationalism.

References

[1] Joshua H. Howard, “‘Music for a National Defense”: Making Martial Music during the Anti-Japanese War,” Crosscurrents: East Asian History and Culture Review E-Journal 13 (2015): 1-50. Available here.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Judy Yung, Gordon H. Chang, and H. Mark Lai, ed., Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present (University of California, 2006), 204-205; Yunxiang Gao, Arise Africa, Roar China: Black and Chinese Citizens of the World in the Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

[4] Liu Liangmo, “Must Fight Fascism at Home and Abroad to Keep This a People’s War,” Pittsburgh Courier, 05 June 1943: 6.

[5] Liu Liangmo., “Demands for a Second Front Shows Relationship of Racial Problems,” Pittsburgh Courier, 10 October 1942: 7

[6] Bass had a long history of activity working with the UNIA, the NAACP, both major political parties and the CPUSA. She was a leader in the struggle to fight racist covenants in housing developments in Los Angeles and in the struggle to free the Scottsboro Boys. In 1952 Bass was the Vice-Presidential candidate of the Progressive Party, running on a platform directly challenging the Cold War at the height of the McCarthyite witch-hunts.

[7] Liu Liangmo, “Will India Be Another Burma? Colored Races Have Big Stake in War,” Pittsburgh Courier, 07 November 1942: 7.

[8] The Council on African Affairs (CAA) was the principal Pan-African organization of the time. Paul Robeson was chairman, W.E.B DuBois was vice-chair and Communist Alphaeus Hunton played a major organizational role. The CAA played a particularly prominent role in building links between the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa and the Black Liberation Movement in the U.S. The CAA would be driven out of existence by the anti-communist witchhunts of the 1950s.

[9] “Enthusiastic Mass Meeting on India,” News of Africa, 01 October 1942. Available here.

[10] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Claudia Jones: Part 1 of 4.” Available here.

[11] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Paul Robeson: Part 4 of 4.” Available here.

[12] Liu Liangmo, “The Poll Tax Bill,” Pittsburgh Courier, 25 December 1943: 6.

[13] Ibid., 7.

[14] Marc Gallicchio, “Colouring the Nationalists: The African-American Construction of China in the Second World War,” The International History Review 20, no. 3 (1998): 579-582.

[15] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: To Cure China’s Deep Wounds, We Must Wipe Out All Forms of ‘Ism’s and Prejudice,” Pittsburgh Courier, 19 December 1942: 15.

[16] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: Southern Filibuster Senators Were Killing Democracy When They Thought They Were Killing Time,” Pittsburgh Courier, 05 December 1942: 15.

[17] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: Time Has Come for Allies to Declare Positive Policy of Military Aid to China,” Pittsburgh Courier, 29 May 1943: 6.

[18] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: Democracy Is Being Practiced by China’s Fighting ‘Red Army,”’ Pittsburgh Courier, 29 July 1944: 7.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Liu Liangmo, “China Speaks: Mr. Liu Warns Us to Guard Against Schemes of Fascist Agents In Our Midst,” Pittsburgh Courier, 03 February 1945: 6.

[21] “Brooks Tells of Entry Into China,” Chicago Defender, 10 February 1945: 2.

[22] Dong was an early member of the Chinese Communist Party as well as a Long March Veteran by this point and would go on to be both the Vice-President and President of China.

[23] Hunton has been called the “Unsung Valiant” for his extensive, yet mainly buried contributions to Black Liberation. Dr. Hunton was a Howard University professor, union organizer for the AFT, executive board member of the National Negro Congress, leader of the anti-police brutality movement in Washington D.C., a member of the Communist Party and the backbone of both the Council of African Affairs and W.E.B. Du Bois’ Encyclopedia Africana project. Hunton would pass away in 1970 in Zambia where Kenneth Kaunda wept at his graveside.

[24] Tony Pecinovsky, ed., The Cancer of Colonialism: W. Alphaeus Hunton, Black Liberation, and the Daily Worker 1944-1946 (New York: International Publishers, 2021), 277.

[25] Joseph Tse-Hei Lee, “Co-Optation and Its Discontents: Seventh-Day Adventism in 1950s China,” Frontiers of History in China 7, no. 4 (2012): 582–607.

[26] Imari Obadele, Free the Land! (Washington: House of Songhay, 1984), 18.

[27] Harry Belafonte and Helen Rosen, “Harry Belafonte: An exception wants to change the rule,” New China, June 1976: 17.