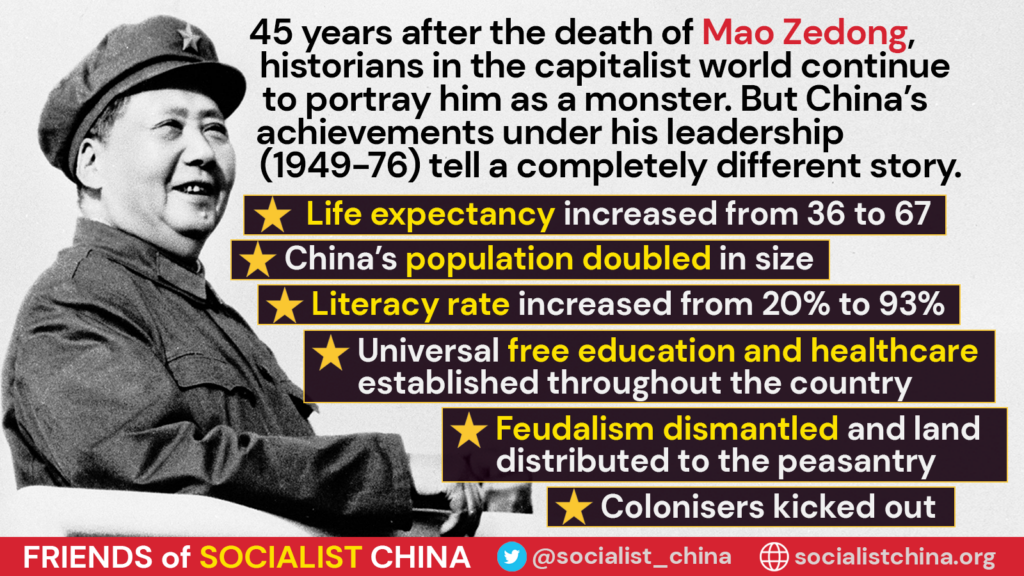

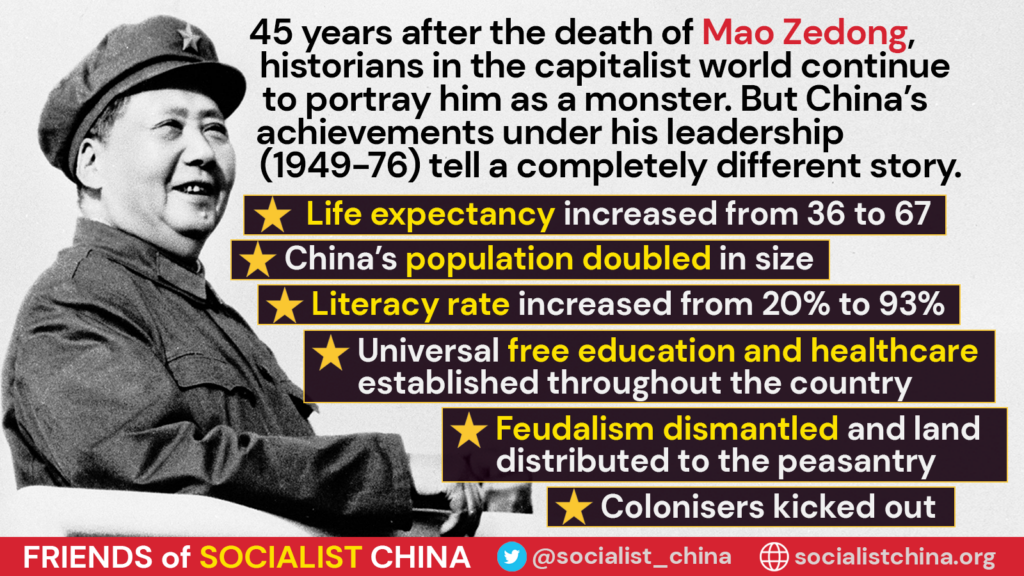

9 September marks the 45th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s death. After all this time, historians in the capitalist world continue to portray Mao as a monster. But China’s achievements under his leadership (1949-76) tell a completely different story.

9 September marks the 45th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s death. After all this time, historians in the capitalist world continue to portray Mao as a monster. But China’s achievements under his leadership (1949-76) tell a completely different story.

This reflection on the history of the CPC, written by Qu Qingshan – Director of the Central Institute of Party History and Literature of the CPC Central Committee – was originally published in Qiushi. It provides an overview of each generation of leadership of the CPC (under Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao and Xi Jinping) and describes how they each feed in to an overall trajectory towards an advanced socialism and national rejuvenation. It highlights the party’s clear position that Marxism must continue to provide the ideological base of its work: “If we deviate from Chinese socialism, all our previous efforts will go up in smoke”.

As General Secretary Xi Jinping has said, the past century has witnessed the Communist Party of China (CPC) work with devotion in pursuit of its founding mission, blaze new trails while enduring bitter hardships, and strive toward a brighter future. Since its founding in 1921, the CPC has surmounted one obstacle after another and achieved victory after victory by relying closely on the people. In this ancient land of China, it has brought about epic milestones in the history of human development and made groundbreaking contributions to the Chinese nation.

Continue reading A century of struggle: the glorious achievements and historic contributions of the Communist Party of ChinaWe are republishing this useful historical outline of the CPC by Belgian journalist Marc Vandepitte. The article first appeared on ChinaSquare (in Dutch), and the English translation was first published on Global Research.

Historical context

For centuries, China had been a leading and powerful empire. That situation changed dramatically after the opium wars starting in 1840.[i] The country was relegated to the status of a semi-colony. Large areas were occupied by foreign powers or fell under their sphere of influence. The imperialist countries destroyed the fledgling industrialization. The population was totally impoverished, riddled with famines.[ii] Tens of millions of Chinese perished during that period through deprivation and political violence. It was also during this period that the black slave trade was replaced by the yellow trade in Chinese people.

Repeatedly, the Chinese revolted against the poor living conditions and for national independence. In 1911 there was a revolution in which the emperor was ousted. The new president Sun Yat-sen was the founder of the Republic of China. However, he failed to get rid of foreign domination and the feudal structures of the country.

That was the context in which, ten years later, thirteen men met in secret to establish a new, Communist Party (CPC). One of them was Mao Zedong. Their great example was the Russian Revolution of 1917. At the time, the party had only 53 members.

Continue reading A hundred years of the Communist Party of ChinaWe are pleased to republish this fascinating history, written by Zhang Wei and published in the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries‘ quarterly magazine ‘Voice of Friendship’ (June 2021), about the first international Marxist study group in Shanghai. The group was supported by Soong Chingling and included such legendary friends of China as Rewi Alley, Agnes Smedley and Helen Foster Snow.

In 1934, encouraged and supported by Soong Ching Ling, about 20 Chinese and foreign leftists established the first international Marxist study group in Shanghai. They studied classic theories, conducted social research, discussed current affairs and actively joined in and assisted the struggle of the Communist Party of China. In fact, the group became the foreign ally of the Chinese revolution.

Rewi Alley, a core member of the study group, was a social activist and writer from New Zealand. At the time, he was chief inspector of the fire department and the chief of the industrial department under the municipal council in the Shanghai international settlement. He was shocked to witness a large number of Chinese people in deep distress during an inspection of the factories. He gave an important description of the study group in the 1980s when recalling those days. He presented a clear list of the members of the group as follows:

“In 1934, like-minded people gradually gathered together to discuss politics. The idea was mainly put forward by German political economy writer Hans Shippe. He wrote articles for the English magazine Pacific Affairs under the pen name Asiaticus. His Chinese name is Xibo. Agnes Smedley said that “we were supposed to know the theories,” but she was too busy and didn’t understand the theories herself. Alec Camplin, an electrical engineer who lived in the same apartment with me in a three-story building on Yuyuan Road, joined our study group. There was also Dr. Hatem, whom Agnes considered a potential participant for the revolution. Other members included the young Austrian progressive Ruth Weiss; Hans Shippe’s wife, Gertrude Rosenberg; the Dutch manager of the leftist Zeitgeist Book Store, Irene Wiedemeyer; four secretaries of the Young Women’s Christian Association, namely, Talitha Gerlach, Maud Russell, Lillian Haass, and Deng Yuzhi; and a teacher at Medhurst High School, Cao Liang. Hans Shippe served as our political instructor. Later, he was killed by enemies while working in the New Fourth Army at Yimeng Mountain, Shandong.”

Continue reading The first international Marxist study group in ShanghaiThe Communist Party of China (CPC) was formed a century ago, in July 1921. From that time up to the present day, it has led the Chinese Revolution – a revolution to eliminate feudalism, to regain China’s national sovereignty, to end foreign domination of China, to build socialism, to create a better life for the Chinese people, and to contribute to a peaceful and prosperous future for humanity.

In this video lecture, Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez argues that, while the Chinese Revolution has taken numerous twists and turns, and while the CPC leadership has adopted different strategies at different times, there is a common thread running through modern Chinese history: of the CPC dedicating itself to navigating a path to socialism, development and independence, improving the lot of the Chinese people, and contributing to a peaceful and prosperous future for humanity.

The video is based on the essay No Great Wall: on the continuities of the Chinese Revolution.

This feature length documentary aired by CGTN last week provides a vivid account of the lifelong dedication to the Chinese revolution on the part of communist fighters David and Isabel Crook and of the love and respect in which they have been held by successive generations of Chinese people from all walks of life.

Review written by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Keith Bennett

The 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China has been the occasion for many grand and impressive events throughout July. 1921, which has also been playing in selected cinemas in Britain and Ireland, and doubtless elsewhere, is the film for the centenary.

A feature film, with special effects worthy of any Hollywood blockbuster, it also features some documentary footage, skilfully heightening the sense of both drama and realism.

Whilst 1921 is focused on that momentous year, it deploys flashbacks as far as the 1850s, showing China’s degradation to a semi-colonial and semi-feudal ruined nation and then at its conclusion a potted but vivid historical reconstruction of subsequent years, which culminates in Chairman Mao proclaiming the founding of the People’s Republic on October 1st 1949, as well as Young Pioneers visiting the restored site of the first party congress 100 years later.

A similar historical technique is deployed to depict aspects of some of the key characters, including such pioneering Chinese communists as Li Dazhao, Chen Duxiu, Li Da and, of course, Mao Zedong. Particularly moving is the depiction of the tragic and heroic fates of some of the key early martyrs of Chinese communism, including Yang Kaihui, Mao’s first wife and great love. This provides a raw and poignant contrast to the youthful idealism, frenetic activity and infectious optimism of many of the key characters as they throw themselves into the preparations for the founding of the party whilst simultaneously immersing themselves in the surging movement of the young but extremely militant Chinese working class along with the youth and students. Shanghai, in particular, where the party was founded, is accurately depicted as a playground for wealthy Chinese and above all for foreign overlords, but as a living hell for the masses of Chinese people.

Continue reading Film review: 1921 – A vivid panorama of revolutionIn this interesting video of a webinar organised by our friends in the Society for Anglo-Chinese Understanding (SACU) the distinguished Sinologist Dr Frances Wood discusses with Michael Crook about his family’s long connection with China, the Chinese cooperative movement and some of the many British people who supported and helped the Chinese revolution.

Michael was born and brought up in China. He is the son of David and Isabel Crook, communists, internationalists and staunch supporters of the Chinese revolution. Born in 1915, Isabel still lives in Beijing. In 2019, President Xi Jinping awarded her the Friendship Medal of the People’s Republic of China. Among the small number of other recipients was Cuban revolutionary leader Raúl Castro.

In this session for the Marx Memorial Library on 1 July 2021, Jenny Clegg explores how Mao adapted Marxist ideology to drive the Chinese peasant revolution from 1925-1949.

Introduction

Edgar Snow’s famous book Red Star over China opens with a series of questions he was looking to answer as he set off for Yenan in 1936: was the CPC a genuine Marxist Party or just a bunch of Red bandits? was the Red Army essentially a mob of hungry brigands as the Right wing KMT Nationalists made out?

From the Left also, Mao was being accused of departing from proletarian politics – for Trotsky the CPC under Mao’s leadership had been ‘captured by the peasants’ rich peasants at that.

Today similar scepticism is directed at whether or not China is genuinely socialist referencing these doubts about the earlier CPC history.

Mao was indeed a peasant leader; the Communist Party could not have come to power without the support of hundreds of millions of peasants – they joined its mass organisations, they joined the Party itself, they carried out and conformed with its policies, and they gave material support in paying taxes and enlisting in its armies.

Mao’s strategy of protracted revolution, building Red bases in the countryside to encircle the towns, is familiar to most people and will not be my focus here.

To answer the question ‘was Mao a Marxist’ it might be expected then that I start with his essays on philosophy – On Practice and On Contradiction. But these essays in themselves are not the focus of my discussion either.

Continue reading Jenny Clegg: Was Mao a Marxist?The following is the text of a speech given by British author, academic and campaigner Jenny Clegg at a recent webinar hosted by the Morning Star and Friends of Socialist China to celebrate the centenary of the CPC. Jenny discusses China’s unique contributions to Marxism, as well as outlining the history of the revolution and analysing the reasons for its continuing successes.

The story of how the CPC, founded in secret by just a handful of people, grew into an organisation of some 95 million members is truly remarkable.

It is a story that goes together with that of China’s transformation from the ‘Sick Man of Asia’ into the world’s second largest economy. It is the Party that provided the political architecture that has made this possible.

Taking stock at 100 years means looking not only at China’s achievements but also what this has meant – and means – for the world.

The CPC’s story is one of twists and turns, of tenacity against adversity, retreating when retreat was necessary but also daring to seize the time when the opportunity arose. What has given the CPC its strength, its courage to face reality, to learn from mistakes, was and is Marxism. For the CPC, Marxism is not a dogma, but a set of tools applied concretely to solve China’s problems.

The key to the success of the Revolution in 1949 lay mainly in the Party’s ability to mobilise the people effectively both around national and around class goals. For this it drew on Marxist class analysis to devise a revolutionary strategy of shared benefit so as to unite all who could be united in the common goals of ending foreign domination and building the nation.

Fundamental here was land reform which gained the CPC the support of hundreds of millions of peasants – they participated in its mass organisations, they joined the Party itself, they carried out and conformed with its policies, and they gave material support in paying taxes and enlisting in its armies.

China’s contribution to the defeat of worldwide fascism in 1945 is often overlooked in the West. It was Communist resistance together with the Nationalist armies that kept Japanese troops bogged down in China so that the Soviets could concentrate all their forces against the Nazis on the Western front. This cost up to 20 million Chinese lives. Nor is it widely understood that China the first country to end colonial rule as the Allies agreed to give up the Unequal Treaties in 1943. China was to be one of the four founding members of the United Nations and the CPC was present at the occasion.

This example of how the Chinese people, led by a Communist Party, gained liberation in 1949 shone a bright light for colonised people around the world. Its experience of people’s war, revolution and the transformation of rural society was to be the inspiration for national liberation movements in many different countries in the years to come.

Continue reading Jenny Clegg reflects on a hundred years of the CPCWe are republishing this article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez, which originally appeared in the Morning Star on 9 July 2021. It is the sixth and final article in a series about the history of the Communist Party of China, which celebrated its centenary on 1 July 2021.

Many consider that “reform and opening up” was a total transformation of Chinese economics and politics and a negation of the first three decades of socialist construction.

Certainly, the strategy adopted by the Deng Xiaoping leadership from 1978 was in part designed to correct certain mistakes and imbalances; however, it was also a response to changing objective circumstances — specifically, a more favourable international environment resulting from the restoration of Beijing’s seat at the United Nations (1971) and the rapprochement between China and the US.

Thomas Orlik, chief economist at Bloomberg Economics, correctly observes that, “When Deng Xiaoping launched the reform and opening process, friendly relations with the United States provided the crucial underpinning. The path for Chinese goods to enter global markets was open.”

So too was the door for foreign capital, technology and expertise to enter China — first from Hong Kong and Japan, then the West. Then premier Zhou Enlai reportedly commented at the time of US secretary of state Henry Kissinger’s historic visit to Beijing in 1971 that “only America can help China to modernise.” Even allowing for Zhou’s legendary diplomatic eloquence, this statement nevertheless contains an important kernel of truth.

Mao and Zhou had seen engagement with the US as a way to break China’s international isolation. The US leadership, meanwhile, saw engagement with Beijing as a way to perpetuate and exacerbate the division between China and the Soviet. Union.

The tragic reality of the split in the world communist movement is that everyone was triangulating; for its part, the Soviet leadership was hoping to work with the US to undermine and destabilise China.

Continue reading A century of the Communist Party of China: No Great WallFriends of Socialist China co-editor Danny Haiphong interviews Carl Zha, political analyst and host of the popular Silk and Steel podcast, to explain the underlying reasons for the Communist Party of China’s widespread popular support. The interview appeared first on the Black Agenda Report presents: The Left Lens Youtube channel.

We are republishing this article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez, which originally appeared in the Morning Star on 2 July 2021. It is the fifth in a series of articles about the history of the Communist Party of China, which celebrated its centenary on 1 July 2021.

From 1978, the post-Mao Chinese leadership embarked on a process of “reform and opening up” — gradually introducing market mechanisms to the economy, allowing elements of private property, and encouraging investment from the capitalist world.

This programme posited that, while China had established a socialist society, it would remain for some time in the primary stage of socialism, during which period it was necessary to develop a socialist market economy — combining planning, the development of a mixed economy and the profit motive — with a view to maximising the development of the productive forces.

Deng Xiaoping, who had been one of the most prominent targets of the Cultural Revolution and who had risen to become de facto leader of the CPC from 1978, theorised reform and opening up in the following terms: “The fundamental task for the socialist stage is to develop the productive forces.

“The superiority of the socialist system is demonstrated, in the final analysis, by faster and greater development of those forces than under the capitalist system.

“As they develop, the people’s material and cultural life will constantly improve… Socialism means eliminating poverty. Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism.”

Was this the moment the CPC gave up on its commitment to Marxism? Such is the belief of many.

Continue reading A century of the Communist Party of China: Reform and opening up — the great betrayal?This webinar was held on Zoom on 3 July 2021, organised by the Morning Star with the support of Friends of Socialist China.

The speakers were:

All the speeches were excellent. You can view the video on YouTube (embedded below).

President Xi Jinping gave a speech in Tiananmen Square on 1 July 2021 to mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China. It features a succinct and powerful analysis of the party’s history and its enduring relevance to the project of Chinese socialism and contributing to a peaceful and prosperous world. Below we reproduce the official English translation of the text.

Comrades and friends,

Today, the first of July, is a great and solemn day in the history of both the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation. We gather here to join all Party members and Chinese people of all ethnic groups around the country in celebrating the centenary of the Party, looking back on the glorious journey the Party has traveled over 100 years of struggle, and looking ahead to the bright prospects for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

To begin, let me extend warm congratulations to all Party members on behalf of the CPC Central Committee.

On this special occasion, it is my honor to declare on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. This means that we have brought about a historic resolution to the problem of absolute poverty in China, and we are now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. This is a great and glorious accomplishment for the Chinese nation, for the Chinese people, and for the Communist Party of China!

Comrades and friends,

The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. After the Opium War of 1840, however, China was gradually reduced to a semi-colonial, semi-feudal society and suffered greater ravages than ever before. The country endured intense humiliation, the people were subjected to great pain, and the Chinese civilization was plunged into darkness. Since that time, national rejuvenation has been the greatest dream of the Chinese people and the Chinese nation.

To save the nation from peril, the Chinese people put up a courageous fight. As noble-minded patriots sought to pull the nation together, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Movement, the Reform Movement of 1898, the Yihetuan Movement, and the Revolution of 1911 rose one after the other, and a variety of plans were devised to ensure national survival, but all of these ended in failure. China was in urgent need of new ideas to lead the movement to save the nation and a new organization to rally revolutionary forces.

With the salvoes of Russia’s October Revolution in 1917, Marxism-Leninism was brought to China. Then in 1921, as the Chinese people and the Chinese nation were undergoing a great awakening and Marxism-Leninism was becoming closely integrated with the Chinese workers’ movement, the Communist Party of China was born. The founding of a communist party in China was an epoch-making event, which profoundly changed the course of Chinese history in modern times, transformed the future of the Chinese people and nation, and altered the landscape of world development.

Continue reading Xi Jinping’s speech on the centenary of the Communist Party of ChinaThe following is the main body of a speech delivered by Friends of Socialist China Co-Editor Keith Bennett at a dinner held in West London on Sunday June 27 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China.

The event was organised and hosted by Third World Solidarity and its Chair, Mushtaq Lasharie, a distinguished political and social activist in Pakistan and Britain. It was attended by a number of prominent members of the Pakistani community in Britain and veteran friends of China from various walks of life.

This coming Thursday, July 1st, marks the Communist Party of China’s centenary.

Whatever your opinions, this is an important occasion. This party has a membership of some 92 million people. Considerably greater than the entire population of the UK. It leads a country of 1.4 billion people. That country is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council and is the world’s second largest economy. By some measures it is already the largest economy. Whether it be international financial crisis, pandemic, climate change or regional hotspots, the management and solution of global problems cannot today be considered separate from the role of China.

To take this snapshot of where China is today is to reflect on the extraordinary journey this country has undergone since some 13 people, representing a little over 50 members, met in Shanghai, a city then under the effective control of foreign imperialists, in conditions of great secrecy and danger, to found the communist party.

With a history of some 5,000 years, China is the world’s longest, continuous and recorded civilisation. Its origins are roughly contemporaneous with the Indus Valley civilisation centred on today’s Sindh province in Pakistan. Many of the world’s great inventions, such as printing, the compass, gunpowder (which the Chinese used for fireworks not for military purposes) and countless others originated from China. If one looks at the last twenty centuries of human history, China was the largest economy in the world for about 17 of them. The other biggest economy was that of an obviously pre-partitioned India. Together these civilisations traded with their counterparts as far as Europe along the ancient silk routes that in considerable measure prefigure today’s Belt and Road Initiative.

However, history does not develop in a straight line but according to a process of uneven development.

Western powers, in time followed by Japan, embarked on a process of colonial expansion, dividing the wealth and riches of the world amongst themselves and fuelling their industrial revolutions.

China, in turn, under the rule of feudal dynasties, fell into a period of complacency, stagnation and decline. It was ripe for picking by greedy, rapacious imperialist powers.

Whilst never completely colonised China became a semi-colonial, semi-feudal country. Bits of territory were snatched away. Unequal treaties were imposed. Imperialist powers enjoyed extra territorial privileges in major cities and elsewhere. The mass of Chinese people endured unimaginable misery.

Perhaps most criminally of all, British capitalists, organised, for example in the East India Company, forced opium onto the Chinese market, leading to terrible problems of addiction for the Chinese and enormous profits for the British.

When a patriotic Chinese official, Lin Zezu, attempted to stamp out this trade in death the British response was war. In the name of ‘free trade’ of course. Two opium wars resulted in bitter defeats for China, not least the loss of Hong Kong. Those in the Conservative Party, and indeed the Labour Party, who continue to speak of Britain’s supposed ‘responsibilities’ towards the people of Hong Kong should do more to reflect on, and repent for, that shameful history.

Continue reading Speech celebrating the 100th anniversary of the founding of the CPCWe are republishing this article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez, which originally appeared in the Morning Star on 25 June 2021. It is the fourth in a series of articles about the history of the Communist Party of China, which celebrates its centenary on 1 July 2021.

The Cultural Revolution started in 1966 as a mass movement of university and school students, incited and encouraged by Mao and others on the left of the CPC leadership.

Student groups formed in Beijing calling themselves Red Guards and taking up Mao’s call to “thoroughly criticise and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois ideas in the sphere of academic work, education, journalism, literature and art.”

The students produced “big-character posters” (dazibao) setting out their analysis against, and making their demands of, anti-revolutionary bourgeois elements in authority.

Mao produced his own dazibao calling on the revolutionary masses to “Bombard the Headquarters” — that is, to rise up against the reformers and bourgeois elements in the party.

These developments were synthesised by the CPC central committee, which in August 1966 adopted its Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution: “Our objective is to struggle against and overthrow those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road; to criticise and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic ‘authorities’ and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art and all other parts of the superstructure not in correspondence with the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.”

Thus the aims of the Cultural Revolution were to stimulate a mass struggle against the supposedly revisionist and capitalist restorationist elements in the party; to put a stop to the hegemony of bourgeois ideas in the realms of education and culture; and to entrench a new culture — socialist, collectivist, modern.

This mass movement, only partially under the control of the party, quickly became chaotic. Universities were closed. Red Guards occupied and ransacked the Foreign Ministry.

Han Suyin describes the atmosphere of the early days of the Cultural Revolution: “Extensive democracy. Great criticism. Wall posters everywhere. Absolute freedom to travel. Freedom to form revolutionary exchanges. These were the rights and freedoms given to the Red Guards, and no wonder it went to their heads and very soon became total licence.”

There was no small amount of violence. Many of those accused by the Cultural Revolution Group (CRG) suffered horrible fates.

Posters appeared with the slogan “Down with Liu Shaoqi! Down with Deng Xiaoping! Hold high the great red banner of Mao Zedong thought.”

Liu’s books were burned in Tiananmen Square. He was expelled from all positions and arrested, interrogated, confined to an unheated cell, and denied medical care. He died under house arrest in 1969.

Peng Dehuai, former Defence Minister and the leader of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s operations in the Korean War, had been forced into retirement in 1959 after criticising the Great Leap Forward.

Jiang Qing – Mao’s wife, and a leading figure in the CRG – sent Red Guards to arrest him. He was repeatedly beaten and interrogated, and died in a prison hospital in 1974.

Although Mao had only intended it to last for a few months, the Cultural Revolution only came to its conclusion shortly before Mao’s death in 1976, albeit with varying intensity — realising that the situation was getting out of control, in 1967 Mao called on the army to help establish order and reorganise production. However, the situation flared up again with the ascendancy of the “Gang of Four” from 1972.

Historians in the capitalist countries tend to present the Cultural Revolution in the most facile and vacuous terms. To them, it was simply the quintessential example of Mao’s obsessive love of violence and power; just another episode in the long story of communist authoritarianism. But psychopathology is rarely the principal driving force of history.

In reality, the Cultural Revolution was a radical mass movement. Millions of young people were inspired by the idea of moving faster towards socialism, of putting an end to feudal traditions, of creating a more egalitarian society, of fighting bureaucracy, of preventing the emergence of a capitalist class, of empowering workers and peasants, of making their contribution to a global socialist revolution, of building a proud socialist culture unfettered by thousands of years of Confucian tradition. They wanted a fast track to a socialist future. They were inspired by Mao and his allies, who were in turn inspired by them.

Such a movement can get out of control easily enough, and it did. Mao can’t be considered culpable for every excess, every act of violence, every absurd statement (indeed he intervened at several points to rein it in), but he was broadly supportive of the movement and ultimately did the most to further its aims.

Mao had enormous personal influence – not solely powers granted by the party or state constitutions, but an authority that came from being the chief architect of a revolutionary process that had transformed hundreds of millions of people’s lives for the better. He was as Lenin was to the Soviet people, as Fidel Castro remains to the Cuban people. Even when he made mistakes, these mistakes were liable to be embraced by millions of people.

The Cultural Revolution is now widely understood in China to have been misguided. The political assumptions of the movement — that the party was becoming dominated by counter-revolutionaries and capitalist-roaders; that the capitalist-roaders in the party would have to be overthrown by the masses; that continuous revolution would be required in order to stay on the road to socialism — were explicitly rejected by the post-Mao leadership of the CPC, which pointed out that “the ‘capitalist-roaders’ overthrown … were leading cadres of party and government organisations at all levels, who formed the core force of the socialist cause.”

The turmoil of the Cultural Revolution impeded the country’s development and brought awful tragedy to a significant number of people. What so many historians operating in a capitalist framework fail to understand is why, in spite of the chaos and violence of the Cultural Revolution, Mao is still revered in China. For the Chinese people, the bottom line is that his errors were “the errors of a great proletarian revolutionary.”

It was the CPC, led by Mao and on the basis of a political strategy principally devised by him, that China was liberated from foreign rule; that the country was unified; that feudalism was dismantled; that land was distributed to the peasants; that the country was industrialised; that a path to women’s liberation was forged.

The excesses and errors associated with the last years of Mao’s life have to contextualised within this overall picture of unprecedented, transformative progress.

The pre-revolution literacy rate in China was less than 20 percent. By the time Mao died, it was around 93 percent. China’s population had remained stagnant between 400 and 500 million for a hundred years or so up to 1949. By the time Mao died, it had reached 900 million. A thriving culture of literature, music, theatre and art grew up that was accessible to the masses of the people. Land was irrigated. Famine became a thing of the past. Universal healthcare was established. China – after a century of foreign domination – maintained its sovereignty and developed the means to defend itself from imperialist attack.

Hence the “Mao as monster” narrative has little resonance in China. As Deng Xiaoping himself put it, “without Mao’s outstanding leadership, the Chinese revolution would still not have triumphed even today. In that case, the people of all our nationalities would still be suffering under the reactionary rule of imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat-capitalism.”

Furthermore, even the mistakes were not the product of the deranged imagination of a tyrant but, rather, creative attempts to respond to an incredibly complex and evolving set of circumstances. They were errors carried out in the cause of exploring a path to socialism – a historically novel process inevitably involving risk and experimentation.

This article by Carlos Martinez, “Will China Suffer the Same Fate as the Soviet Union?”, was published in World Review of Political Economy, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 2020): pp. 189-207.

Carlos Martinez is an independent researcher and political activist from London, Britain. His first book, The End of the Beginning: Lessons of the Soviet Collapse, was published in 2019 by LeftWord Books. His main areas of research are the construction of socialist societies (past and present), progressive movements in Latin America, and multipolarity.

Abstract: It was widely assumed in the West following the collapse of European socialism that China would undergo a similar process of counter-revolution. This article seeks to understand why, three decades later, this hasn’t happened, and whether it is likely to happen in the foreseeable future. The article contrasts China’s “reform and opening up” process, pursued since 1978, with the “perestroika” and “glasnost” policies taken up in the Soviet Union under the Gorbachev leadership. A close analysis of the available data makes it clear that China’s reform has been far more successful than the Soviet reform; that, in contrast to the Soviet Union in the 1980s, all the key quality of life indicators in China have undergone significant improvement in the last forty years, and China is emerging as a global leader in science, technological innovation and environmental preservation. The article argues that the disparate outcomes in China and the Soviet Union are the result primarily of the far more effective economic strategy pursued by the Chinese government, along with the continued strengthening of the Communist Party of China’s leadership.

We should think of China’s communist regime quite differently from that of the USSR: it has, after all, succeeded where the Soviet Union failed. (Jacques 2009, 535)

This article addresses the reasons for the collapse of the Soviet Union, and seeks to understand whether the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is vulnerable to the same forces that undermined the foundations of European socialism. What lessons can be drawn from the Soviet collapse? Has capitalism won? What future does socialism have in the world? Is there any escape for humanity from brutal exploitation, inequality and underdevelopment? Is there a future in which the world’s billions can truly exercise their free will, their humanity, liberated from poverty and alienation?

The conclusions I draw are that China is following a fundamentally different path to that of the Soviet Union; that it has made a serious and comprehensive study of the Soviet collapse and rigorously applied what it has learnt; that the People’s Republic of China remains a socialist country and the driving force towards a multipolar world; that, in spite of the rolling back of the first wave of socialist advance, Marxism remains as relevant as ever; and that, consequently, socialism has a bright future in the world.

Continue reading Will China Suffer the Same Fate as the Soviet Union?We are republishing this useful article from Workers World outlining the history of the Communist Party of China and calling on progressives and anti-war activists in the West to oppose the US-led New Cold War.

Workers World Party, founded in 1959, is a Marxist-Leninist party in the U.S. From its beginning, Workers World has been a staunch supporter of the 1949 Chinese Revolution, with great appreciation for the guiding role of the Communist Party of China in that revolution. As a revolutionary working-class party in the center of world imperialism, we are determined to defend all the gains of our class on a world scale. We intend to make the following essay saluting the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China available to readers in the United States, so we have included some history not widely known in the U.S. that shows the differences between the U.S. and China.

For 5,000 years, China was one of the world’s most advanced societies in culture, art and technology. It came under attack in the 18th and 19th centuries from powers whose rapid capitalist development gave them a temporary advantage in military and industrial power. This advantage led to several hundred years of the colonial looting of China and much of East and South Asia. Unequal treaties and military occupation reduced China to a country of staggering poverty, famines, social chaos, enforced underdevelopment and wars.

Most people brought up in the United States know little of the past intervention by the U.S. and other imperialist countries into China. They are unaware that, in the 19th century, armed units from the U.S., Britain, France, Germany and Japan imposed their will on Chinese cities. The U.S. Navy had fleets of armored ships patrolling Chinese rivers and coastal waters. This most brutal gunboat diplomacy imposed unequal treaties to reinforce their military occupations, while making China pay these imperialist countries huge indemnities. With U.S. participation, Britain unleashed two Opium Wars on China to enforce its “right” to sell opium. They called it “free trade.”

When students mobilized against Chinese rulers who were compliant to the imperialists, they were repressed. A nationalist movement grew. Until 1921, despite the courage of its young participants, they were unable to coalesce into a movement that could mobilize the masses of people — one-quarter of the world at that time — and liberate China.

Continue reading Salute on the Communist Party of China’s 100th AnniversaryWe are republishing this article by Friends of Socialist China co-editor Carlos Martinez, which originally appeared in the Morning Star on 18 June 2021. It is the third in a series of articles about the history of the Communist Party of China, which celebrates its centenary on 1 July 2021.

To this day, the most popular method for casually denigrating the People’s Republic of China and the record of the Communist Party of China (CPC) is to cite the alleged crimes of Mao Zedong who, from the early 1930s until his death in 1976, was generally recognised as the top leader of the Chinese Revolution.

After all, if the CPC was so dedicated to improving the lot of the Chinese people, why did it engage in such disastrous campaigns as the Great Leap Forward (GLF) and the Cultural Revolution?

The GLF, launched in 1958, was an experimental programme designed to achieve rapid industrialisation and collectivisation; to fast-track the construction of socialism and allow China to make a final break with centuries-old underdevelopment and poverty; in Mao’s words, to “close the gap between China and the US within five years, and to ultimately surpass the US within seven years.”

In its economic strategy, it represented a rejection of Soviet-style urban industrialisation, reflecting the early stages of the Sino-Soviet split. The Chinese were worried that the Khrushchev leadership in Moscow was narrowly focused on the avoidance of conflict with the imperialist powers, and that its support to China and the other socialist countries would be sacrificed at the altar of peaceful coexistence. Hence China would have to rely on its own resources.

The plan for the GLF centred on the modernisation of agriculture, introducing irrigation and modern machinery, breaking down the barrier between town and country by producing some of that machinery in small-scale village factories, and trying to develop productivity — and a socialist spirit — through collectivisation and the formation of people’s communes.

There was a heavy voluntaristic aspect to the campaign; a broad appeal to the revolutionary spirit of the masses. Ji Chaozhu (at the time an interpreter for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later China’s ambassador to Britain (1987-91) notes in his memoirs: “Cadres were to join the peasants in the fields, factories, and construction sites. Even Mao made an appearance at a dam-building project to have his picture taken with a shovel in hand.”

Mao considered the countryside would once again become the “true source for revolutionary social transformation” and “the main arena where the struggle to achieve socialism and communism will be determined.”

The attempt to develop small-scale rural industry was, in the main, unsuccessful. And with millions of peasants drafted into the towns to work in factories, there were too few hands available for reaping and threshing (Alexander Pantsov writes that the “battle for steel had diverted the Chinese leadership’s attention from the grain problem, and the task of harvesting rice and other grain had fallen on the shoulders of women, old men and children.)

Furthermore the GLF coincided with a series of terrible droughts and floods. Adding to the troubles was the fact that, in 1960, the Sino-Soviet split came out into the open and the Soviets hurriedly withdrew their technical advisers.

The result of all this was a contraction in agricultural output, and a consequent deepening of poverty and malnutrition. Liu Mingfu writes that “the Great Leap Forward did not realise the goal of surpassing the UK and US. It actually brought China’s economy to a standstill and then recession.

“It caused a large number of unnatural deaths and pushed China’s global share of GDP from 5.46 per cent in 1957 to 4.01 per cent in 1962, lower than its share of 4.59 per cent in 1950.”

Certain of the GLF’s goals were achieved — most notably the irrigation of arable land. However, overall it failed to meet its objectives and was accompanied by several harmful side effects. It was called off in 1962.

For anti-communists, the GLF provides apparently incontrovertible proof of the monstrous, murderous nature of the CPC — and Mao Zedong in particular. Western bourgeois historians have settled on a figure of 30 million for the estimated number of lives lost in famine resulting from the GLF.

On the basis of a rigorous statistical analysis, Indian economist Utsa Patnaik concludes that China’s death rate rose from 12 per thousand in 1958 (a historically low figure resulting from land reform and the extension of basic medical services throughout the country) to a peak of 25.4 per thousand in 1960.

“If we take the remarkably low death rate of 12 per thousand that China had achieved by 1958 as the benchmark, and calculate the deaths in excess of this over the period 1959 to 1961, it totals 11.5 million. This is the maximal estimate of possible ‘famine deaths.’”

Patnaik observes that even the peak death rate in 1960 “was little different from India’s 24.8 death rate in the same year, which was considered quite normal and attracted no criticism.”

This is an important point. Malnutrition was at that time a scourge throughout the developing world (sadly it remains so in some parts of the planet). China’s history is rife with terrible famines, including in 1907, 1928 and 1942. It is only in the modern era, under the leadership of precisely that “monstrous” CPC, that malnutrition has become a thing of the past in China.

In other words, the failure of the GLF has been cynically manipulated by bourgeois academics to denigrate the entire history of the Chinese Revolution. The GLF was not some outrageous crime against humanity; it was an unsuccessful experiment designed to accelerate the building of a prosperous and advanced socialist society.

In the aftermath of the GLF, Mao’s more radical wing of the CPC leadership became somewhat marginalised, and the initiative fell to those wanting to prioritise social stability and economic growth over ongoing class struggle. Principal among these were Liu Shaoqi (head of state of the PRC, then widely considered Mao’s likely successor) and vice-premier Deng Xiaoping.

Mao and a group of his close comrades began to worry that the deprioritisation of class struggle reflected an anti-revolutionary “revisionist” trend that could ultimately lead to capitalist restoration.

As Mao saw it, revisionist elements were able to rely on the support of the intelligentsia — particularly teachers and academics — who, themselves coming largely from non working-class backgrounds, were promoting capitalist and feudal values among young people. It was necessary to “exterminate the roots of revisionism” and “struggle against those in power in the party who were taking the capitalist road.”

Such worries laid the basis for the Cultural Revolution.